Category: Industrial Revolution 1865-1900

Social Settlement Movement aggregation

1 Settlement Houses from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

2 Settlement Houses in Cleveland from Cleveland State

3 Social Reform and Philanthropic Order

4 Goodrich House from Cleveland Historical

5 A historical report of the sixteen years work at Hiram House

7 From Progressive to Patrician: George Bellamy and Hiram House Social Settlement, 1896-1914

James A. Garfield aggregation

1 The Western Reserve’s Self-Made President By Grant Segall

2 President James A. Garfield: Civil rights activist ahead of his time (with video)

3 James A Garfield Essay from the Miller Center University of Virginia

4 For the briefest time, President Garfield was an inspiration (Washington Post 2/17/13)

5 James A. Garfield: Lifting the Mask

6 The James A Garfield Monument

7 James Garfield Monument from Cleveland Historical

9 Life Portrait of James Garfield (Video) CSPAN

11. Presidents and health: How James A. Garfield’s death changed American medicine Cleveland.com 9.14.16

Henry Chisolm, the Father of Cleveland’s Steel Industry

A two page biography on Henry Chisholm, the father of Cleveland’s Steel industry.

This is from “A History of Cleveland and Its Environs” 1918 Elroy McKendree Avery and is still one of the best essays on Chisolm.

or read below

John D. Rockefeller aggregation

Her Fathers’ Daughter: Flora Stone Mather and Her Gifts to Cleveland by Dr. Marian Morton

Her Fathers’ Daughter: Flora Stone Mather and Her Gifts to Cleveland

By Dr. Marion Morton

Cleveland’s best-known woman philanthropist took no credit for her generosity: “I feel so strongly that I am one of God’s stewards. Large means without effort of mine, have been put into my hands; and I must use them as I know my Heavenly Father would have me, and as my dear earthly father would have me, were he here.” [1] So Flora Stone Mather described the inspirations for her giving: her Presbyterian belief in stewardship – serving (and saving) others – and the example of her father, Amasa Stone. But she expanded her role as grateful daughter, moving beyond philanthropy into political reform and institution-building.

Flora Stone, born in 1852, was the third child of Amasa and Julia Gleason Stone. Her family – parents, brother Adelbert, and sister Clara – moved to Cleveland from Massachusetts in 1851. Her father, a self-taught engineer, built churches, then bridges and railroads, which made his fortune. He arrived in Cleveland as superintendent of the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad, which he had built with two partners. He subsequently directed and built other railroad lines and invested in the city’s burgeoning industries and banks. Thanks to its railroads and lake shipping, petroleum refineries, and iron and steel mills, Cleveland would become an industrial giant.

In 1858, Stone built an elaborate Italianate mansion on Euclid Avenue, a sign that he had arrived socially and financially. He became an ardent Republican and an enthusiastic supporter of the Union side of the Civil War. The war boosted Cleveland’s industries and made Amasa even richer. He kept his son Adelbert out of the Union Army, but lost him anyway when the 20-year-old student at Yale drowned on a school expedition in June 1865.

Julia Gleason had worked as a seamstress before her marriage, but her husband’s financial success and social position meant that daughters Flora and Clara were destined for lives of privilege, defined as marriage and family, in keeping with nineteenth-century ideas about woman’s nurturing and innately domestic nature.

Flora seemed fitted by personality and upbringing for this role. “Small in stature and fragile in health,” “plain and unassuming” in her appearance and habits, [2] she was above all, modest, self-effacing, and compassionate. She dutifully participated in the conventional social life expected of Euclid Avenue women: dinners, receptions, teas, walks and carriage rides, charity benefits, and visits to her affluent, congenial neighbors. Yet she had a lively intelligence and a keen curiosity, honed by her rigorous education and travels abroad. Her intellect and energy made her a leader among her peers even as a young adult: “’Wait until Flora comes. She will know just how to go ahead,’” said her friends.[3] She also had an adventurous spirit, confessing to her fiancé: “I do like to meet new people.”[4] And meet them she did.

Amasa Stone valued education for his daughters – perhaps to enhance their (and his) social status or perhaps to enhance their intellects. He was a funder and the builder of the Cleveland Academy, a private girls’ school, which opened in 1866 across from the Stones’ Euclid Avenue home. Both Clara and Flora attended. Their demanding college preparatory education relied on both Biblical texts and current events and emphasized speaking in public as well as writing.[5] Headmistress Linda Thayer Guilford also taught her young students that they had a moral responsibility to the less fortunate around them.

And there were plenty of the less fortunate in post-Civil War Cleveland. Its population had doubled during the war and continued to grow – 92,829 in 1870 and 160,146 in 1880 – , swelled by immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and soon from all over Europe, as well as by native-born men and women from small towns and villages who saw possibilities in this bustling city on Lake Erie. Often lacking the skills for urban life or earning a living in the city, however, new arrivals often fell upon hard times. The Cleveland Infirmary (or public poorhouse) sheltered – grudgingly – absolutely destitute families. Those who had at least a roof over their heads received an ungenerous supply of food and clothing at the backdoor of the Infirmary. In this almost complete absence of public assistance, private charities, all faith-based, stepped in to help their co-religionists.

Immigrants also turned a small homogeneous town into a prospering city with neighborhoods differentiated by class, ethnicity, or religion. But in the second half of the nineteenth century, before the widespread use of the streetcar and then the automobile allowed the well-to-do to flee the city, these neighborhoods often adjoined one another, so that the less fortunate were not hidden from their more fortunate neighbors.

The population growth that created visible poverty also created great wealth for some: men like Amasa Stone who arrived in Cleveland at the right time with the right skills. And like Stone, a handful became the philanthropists who created Cleveland’s enduring cultural, educational, social welfare, and medical institutions, as well as its recreation facilities. Some of the magnificent gifts of these late nineteenth-century industrialists and bankers still bear their names: Gordon Park, Wade Park Lagoon, Severance Hall, Rockefeller Park, the Mather Pavilion of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University.

All these big donors were men. It would have been almost impossible for a nineteenth-century woman to earn this kind of money. Women acquired wealth by inheriting it or marrying it.

Flora Stone Mather did both. Her marriage in 1881 to Euclid Avenue neighbor Samuel Mather was a love match that brought the couple four children – Samuel Livingstone Mather (born in 1882), Amasa Stone Mather (born in 1884), Constance Mather (born in 1889), and Philip Richard Mather (born in 1894). The Mathers were a more distinguished family than the Stones, dating their American origins back to the famous Puritan ministers, Increase and Cotton Mather. Samuel’s father, Samuel Livingston Mather, came to Cleveland in 1843 to take charge of the family’s holdings, established by his own grandfather, Samuel Mather Jr., a stockholder in the Connecticut Land Company that settled the region. [6]

Although born into a wealthy family, Flora’s husband had made his own fortune. In 1869, he had permanently injured his arm while working in his father’s Michigan ore mines and did not attend Harvard as he had planned. Instead, Samuel continued to work for his father’s company, Cleveland Iron Mining Company, and then founded Pickands Mather, a rival supplier of iron ore and transportation to the steel industry. He also held directorships in several iron and steel companies and banks. When Samuel died in 1931, he was considered the richest man in Ohio although the Great Depression had diminished his wealth. [7]

Amasa Stone’s death in 1883 left Flora an independently wealthy young woman. Stone committed suicide, depressed by his own failing health, his son’s death, and the tragic collapse in 1876 of one of his railroad bridges, which killed 92 passengers and ruined Stone’s reputation. [8] Flora and Clara each inherited $600,000; their husbands, author-diplomat John Hay and Samuel Mather, $100,000, plus whatever money was left over after Stone’s debts and other bequests were paid. [9]

Flora had enough money during her lifetime to make dozens of gifts to local charities – from the Visiting Nurse Association and the Humane Society to the YMCA, the Home for Aged Colored People, and Hathaway Brown School. When she died in 1909 of breast cancer, she left money to a wide range of educational institutions, including Lake Erie College and Tuskegee Institute, various Presbyterian missionary groups, Cleveland Associated Charities, and the Association for the Blind.[10]

Her most compelling interests and her most generous gifts, however, were shaped by her private religious faith that found public expression in serving those in need.

The Stones belonged to First Presbyterian (Old Stone) Church, centrally located on Public Square, close to the Stones’ Euclid Avenue home. The church, founded in 1827, boasted a socially and politically prominent congregation. Like most other wealthy Protestant churches, Old Stone sold or rented pews to its members. In 1855, when the Stones were members, almost half of its pews cost more than $400 a year; eight cost $1,000.[11] Obviously, this custom discouraged membership by the less wealthy.

Perhaps to compensate for the high price of its pews, the congregation also established a tradition of stewardship. Its members established the Western Seamen’s Friend Society in 1830, one of the city’s first charities, which built a chapel and organized a Sunday school to promote the physical and spiritual needs of the men who worked on the canal and the lake.

Although the leadership – lay and clerical – of Protestant churches was male, women carried on most of the institutions’ charitable activities. (They also did most of the fund-raising.) These allowed women a socially sanctioned entrance into the world beyond home and family. Led by Rebecca Rouse, the women of Old Stone founded the city’s first orphanage, the Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, in 1852. This is now Beechbrook, a residential treatment center for children. In 1863, the women established a home for “poor and friendless people” – later called the “Protestant Home for Friendless Strangers” – who were so new to town that they were ineligible for the city Infirmary. [12] Amasa Stone became the first in his family to donate money to this institution, which evolved into Lakeside Hospital and eventually University Hospitals.

Like other Protestant churches, Old Stone experienced waves of religious revivalism in the last decades of the nineteenth century that gained the institution new members and new enthusiasm. In 1866, for example, its pastor, Rev. William H. Goodrich, led a “powerful revival” with “marked indications of the presence of the Spirit” in the Young People’s Meeting.[13] Flora, then an impressionable 14, may well have felt that Spirit. [14]

In 1867, Flora and Clara joined the newly formed Young Ladies Mission Society. The young women did their missionary work in the working-class neighborhood just to the north of the church where they sewed garments and raised funds for the mission church that became North Presbyterian, originally at E. 41st St. and Superior Ave. [15]

This missionary spirit also infused the temperance movement of the 1870s. Temperance was probably the most popular reform of the nineteenth century as American cities grew rapidly. Too much alcohol in a country village was one thing; too much in a congested urban neighborhood was another – obviously more harmful to persons and property. Drinking was also associated with immigrants, especially Irish and Germans, not always welcomed by native-born Clevelanders. And to enthusiastic Protestants, conversion to temperance was the first step to finding salvation and true religion, a belief reinforced by the opposition to temperance by some Catholics.

Temperance had particular appeal to women since male abuse of alcohol harmed women and children. In spring 1874, “praying bands” of Cleveland women descended upon local saloons, pleading with saloon keepers and customers to forswear alcohol. Weeks later, the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was formed in Cleveland; in the last decades of the nineteenth century, it became the largest woman’s organization in the country.

The local branch of the WCTU founded several institutions intended to save men, women, and children from the evils of alcohol. [16] Two have survived: Rainey Institute and Friendly Inn, both neighborhood centers in inner-city Cleveland.

Temperance provided Flora with her first foray into public life as vice president (1874-1876), then president (1877-1881) of the Young Ladies Temperance League (YLTL). The young women were more decorous than the “praying bands,” although equally pious. As president, Flora led their formal meetings, held in various Protestant churches, which began with prayers and featured hymns, and Bible readings. Their group’s stated goal: to stand “against the use of intoxicating liquors [and] to aid in creating an enlightened Christian public sentiment” on the subject. All members took the pledge of total abstinence.[17]

Like the WCTU, the young women believed that the salvation of the soul was closely connected to the salvation of the body, and like their elders, they established institutions for less fortunate women. The first, in 1875, was a lodging house “for friendless young women dependent upon their own exertions for support,” which provided “a refuge from temptation” while jobs and permanent housing were sought. “Nearly all” the young women were “either directly or indirectly, sufferers through the crime of intemperance.”[18] The home sheltered only Protestants and only “the better class of young women … seamstresses, housekeepers, clerks, nurses …” Flora drew up the house rules, which included attending Protestant religious services. [19]

More inclusive and of more lasting importance were the league’s institutions for children. The YLTL briefly took responsibility for a “charity kindergarten for “twenty-one little waifs.” Out of this project in 1880 grew a day nursery. Flora had visited such a nursery in New York City and encouraged the group to start “a similar enterprise” in Cleveland. [20] Here Flora developed personal connections with poor children and their mothers: “”[I] had such a sweet time at the Nursery…. I sat by the fire rocking a cradle and singing to a tired little boy. Then the mothers came for their children and I had a little talk with each one.’”[21] The nursery took all children, regardless of their religious background.

In 1882, the Young Ladies Temperance League became the Young Ladies Branch of the Woman’s Christian Association, whose sole purpose was to establish day nurseries for the children of working mothers. Flora served as the group’s first president. She enlisted the financial support of her former Euclid Avenue neighbor, John D. Rockefeller. [22] In 1888, she herself donated the site of the nursery she named “Bethlehem” to connect it “with the childhood of Christ.” [23] This was one of several day nurseries that the group eventually maintained; the others, however, were named for their benefactors like the Hanna and Wade families. A Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter painted this charming portrait of the Perkins day nursery: “cool, clean, airy rooms filled with bright-faced, happy children” who received meals and medical attention as well as lessons in good behavior; mothers paid five cents a day or whatever they could afford. [24]

In 1894, Flora’s organization became the Cleveland Day Nursery and Kindergarten Association, which operated day nurseries and kindergartens all over the city and trained teachers for public kindergartens. As the Cleveland public school system established its own kindergartens, the association gradually closed theirs but continued to operate day nurseries until it was absorbed into the Center for Families and Children in 1969. Hanna Perkins Center for Child Development is descended from the association.

Although initially inspired by her pious desire to serve the less fortunate, Flora’s next project moved her in the direction of changing the society in which they lived. In 1897 Flora founded and funded Goodrich House, the social settlement at E. 6th and St. Clair Avenue, around the corner from Old Stone and named for her former pastor. Its “object,” Flora wrote, “shall be to provide a center for such activities as are commonly associated with Christian Social Settlement work.” [25] Although a separate institution, the settlement grew out of Old Stone’s clubs and classes for neighborhood children. The first president of the settlement’s board of trustees was the current pastor of Old Stone, Hiram C. Hayden. The settlement’s first director, Starr Cadwallader, was a graduate of Union Theological Seminary.

Settlement houses often had denominational connections. Cleveland’s first settlement, Hiram House, was an offshoot of Hiram College, a Disciples of Christ institution, and was directed by George Bellamy, an ordained minister. The Council Educational Alliance, which evolved into the Jewish Community Center, was initiated in 1899 by the National Council of Jewish Women; Merrick House, in 1919 in the Tremont neighborhood, by the Catholic Christ Child Society.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer in June 1897 waxed ecstatic about Goodrich House, the gift of “Cleveland’s most distinguished woman philanthropist, Mrs. Samuel Mather.” The activities within the “handsome three-story building of brick with stone trimmings and imposing entrances” were “infused with the Christian spirit although no effort is made to prejudice its members in religious matters.” [26]

Settlements sought to solve the pressing problems of urban poverty and social dislocation by easing the transition of immigrants into urban life, expanding upon the faith-based activities spawned by churches and the temperance movement with secular lectures, services, and classes for adults as well as for children. Goodrich House, for example, had a gymnasium, a bowling alley, public baths and a laundry, classes in choral singing, several clubs for boys ( the Garfield and Franklin clubs) and for girls (the Sunshine, Rosebud, and Little Women clubs). [27]

Settlement residents were usually single, middle-class, educated men and women who lived in the settlement in return for leading classes or other activities with its working class neighbors. Goodrich House’s early residents included future Cleveland mayor and U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and reformer-author Frederic C. Howe. Howe later recalled: “Residents … had good food and comfortable rooms; they enjoyed a certain distinction because of their good works.” [28]

Settlements launched the careers of many Progressive reformers because what the residents learned first-hand about the difficult lives of the poor often encouraged them to challenge the political and economic status quo. Goodrich House became “perhaps [the] most liberal settlement” in Cleveland, providing a “public forum for the discussion of social reforms.” [29] In this context, Howe, like Baker, went into reform politics, as did Cadwaller.

By then married with four small children, Flora did not become a resident of Goodrich but was fully engaged in its activities from its beginnings to the end of her life. Its organizational meetings were held at her Euclid Avenue home. She wrote to well-known reformer Jacob Riis for suggestions for a director. He couldn’t help her out, but when Goodrich House opened in April 1897, she invited Riis to its opening; he regretfully declined. [30] She served on the settlement’s House Committee that oversaw its residents and on its executive committee. She provided also for the settlement’s upkeep. Staff had to insist on sticking to a budget so that she would not simply pay all the bills herself.[31] Samuel served on the board of trustees.

As the downtown neighborhood commercialized, Flora participated in the discussion to sell the elaborate building in 1907 and to move farther east to E. 31st St. Flora’s settlement, now located at E. 55th St. and St. Clair, has been renamed Goodrich-Gannett Neighborhood Center after Alice P. Gannett, the settlement’s director from 1917 to 1947. It provides a wide range of programs and services for children and adults as it did when Flora first founded it.

Responding to what she too had learned about the urban poor at Goodrich, as well as in her earlier temperance work, in April 1900, Flora urged the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce to “try to improve the conditions of labor.” “Mrs. Samuel Mather Will Co-operate Very Substantially,” exclaimed the Cleveland Plain Dealer on its front page, when Flora promised to pay the salary of someone to take charge of investigating “working people’s conditions and surroundings in stores, shops, and factories.” [32] Within weeks, however, she decided instead to form at Goodrich House the Consumers League of Ohio (CLO), a local chapter of the National Consumers League. Flora served on the local league’s executive committee from its founding until 1907 when she was made an honorary vice-president.

The league’s goal was to improve the working conditions of women and children: to limit the hours of work, to guarantee a minimum wage, and to ensure that factories, mills, and offices were safe and sanitary. In 1900, more than a third of Cleveland’s female work force (10,600 women) were factory operatives; they worked in all industries but were concentrated in textiles, cigar factories, and laundries. A study in 1908 provided shocking details: women and girls in laundries got paid less than $5 a week; work in candy factories was dangerous and filthy (for both workers and consumers); in garment factories, men did the skilled work and got paid twice what women did.[33]

Although it had no connections with organized religion, the CLO’s concern for women and children had been Flora’s since her days as a temperance activist. In 1905, league president Marie Jenney Howe maintained that the local CLO grew out of Flora’s “friendship” with Florence Kelley, the founder and first general secretary of the national organization. [34] Flora may have met Kelley when she was a resident at Chicago’s famous settlement, Hull House, from 1891 to 1899, just as Flora was making her plans for Goodrich House. Kelley, a Socialist, was also an outspoken activist and reformer. The CLO moved Flora even more decisively from philanthropy into reform politics.

League members used their considerable social status and economic power as middle-class consumers to apply pressure on employers to improve conditions in their shops and factories. For example, in 1901, Flora, with CLO president Belle Sherwin, asked retail store owners to close at noon on Saturday to give their workers an extra half-day off. [35] The league also tried to educate the public about wages and working conditions in factories and shops. Employers who met league standards got the league’s “white label”; shoppers were urged to boycott those who did not. Sherwin reported much progress in 1905: “improvement in lunch and toilet rooms for employees, better sanitation in factories, shorter hours for clerks and, best of all, a cultivation of a ‘shopping conscience.’” [36]

Department stores like William Taylor & Co. advertised that many of their goods carried the “white label” – meaning “clean, sanitary surroundings [for workers], the absence of child labor, the proper treatment of employees, the absence of sweat shop conditions.” [37] But CLO members soon realized that voluntary cooperation of employers with the league “did not prove universally successful … [ and] recognized the need for establishing legal standards.” [38] This realization took women like Sherwin and Howe into politics and the suffrage movement.

Flora died before the local suffrage movement was well underway, but in 1905, she ventured again into reform politics when she joined the local committee to work with the National Child Labor Committee. The goal of the committee, established in 1904 and headed by Owen Lovejoy, was to end child labor. Husband Samuel also sat on the committee, as did Rabbi Moses Gries and Belle Sherwin. [39]

In 1908, Flora, with Marie Jenney Howe, Mrs. Newton D. Baker, and others, organized the Municipal School League. Its purpose was “to increase the interest of women in the school ballot … [and] to maintain the representation of women on the school board.” [40] (Ohio women had gotten right to vote for and serve on local school boards in 1894.)

If Flora’s faith-inspired work for women and children led her into the secular world of political reform, her gifts that followed in Amasa Stone’s footsteps helped to transform the small college for men that he had sponsored into a thriving university that educated both men and women.

His gift of $500,000 had persuaded Western Reserve College, founded in 1826, to move in 1882 from the village of Hudson to the city of Cleveland on properties along Euclid Avenue in what is now University Circle. These had been donated by other benefactors for both Western Reserve and Case School of Applied Science, which had been founded in 1881 by Leonard Case Jr., in downtown Cleveland. Stone stipulated that Western Reserve College was to be re-named Adelbert to honor his son and that $150,000 of this gift was to be spent on buildings and that the remainder would be a permanent endowment. It is not clear whether the gift was inspired by Stone’s grief at the loss of his only son or by his rivalry with Case or whether it was intended to atone for the tragic train wreck. In any case, the gift came with strings attached: not only the college’s new name but a new board of trustees chosen by Stone himself. After his death in 1883, the college received another $100,000. [41]

Generous as Amasa had been, Flora and husband Samuel would ultimately donate to the college more than ten times as much. [42] When her father died, she and Samuel had been married only two years and still lived in Amasa’s home. (The couple built their summer home Shoreby in Bratenahl in 1890 and a grander home on Euclid Avenue in 1910, completed after Flora’s death.) Flora must have been deeply grieved at her father’s death and the contempt which many Clevelanders had for him – despite his wealth and social standing. Her gifts to the college – like his – may have been a way of clearing his name and restoring his reputation.

Her first gifts were to Adelbert College: an endowment in 1888 of $50,000 and $2,500 to the library fund, to which Samuel also contributed. In 1889, she endowed a chair in history. The Cleveland Plain Dealer haled the “MUNICIFENT GIFT,” but Flora, always modest, “treated the subject lightly and impatiently said the sum was so small she didn’t care to speak of it.” [43]

The endowed chair was named for Haydn, then both the college president and Flora’s pastor at Old Stone. Almost all private colleges had financial and other connections to religious denominations, and it was common for college presidents to be clergymen.

Haydn ended coeducation at the college. Women had been admitted, beginning in the 1870s. Although their numbers were small, most were excellent students, and they had a champion in then-college president Carroll Cutler, whose daughter Susan was valedictorian of her class. But the women also enemies among the faculty and trustees, who blamed the college’s low enrollment on its female students and feared that the college would become “over-feminized” if it continued to admit women. Cutler resigned, weary of the battle over coeducation. Haydn assumed the presidency in November 1887 and terminated the admission of women shortly afterwards. This decision generated bitter controversy over the virtues of educating women. During his inaugural address, four women, graduating seniors, walked out of Haydn’s presidential inauguration in protest, leaving the college for good and receiving their college degrees elsewhere. Haydn responded by establishing a separate College for Women under the aegis of Western Reserve College in 1888. [44]

The new College for Women thus got off to a rocky start. Its faculty was drawn from Adelbert College, and for three years, they taught the young women for free in a farmhouse at the corner of Euclid Avenue and Adelbert Road. There was originally no dormitory, no proper chapel, and an ill-equipped gymnasium in a barn.[45]

The first significant gifts to the new College for Women came from Flora’s mother ($5,000) and her brother-in-law, John Hay ($3,000). The first academic building was the gift of Anna M. Harkness, who also donated Harkness Chapel to honor the memory of her daughter Florence. Flora donated $75,000 for the first dormitory, named for Linda Thayer Guilford, and in 1891, she gave another $75,000, most of which was to go into an endowment for the college. The Cleveland Plain Dealer called this “ A Princely Gift. ”[46] In 1901, she donated, (not very) anonymously, the funds for Haydn Hall, a classroom building. She also gave small gifts “from books to … boating permits [,] … making it possible for the young women of the college to enjoy healthful exercise by rowing on the pond in Wade Park.” [47] She and Samuel in 1898 gave $12,000 to the university library. [48]

Adelbert Stone had gone to Yale, but higher education did not figue into Amasa Stone’s plans for his daughters. They might have attended Mount Holyoke College, for example, where Guilford had gone, or to nearby Oberlin College. Instead, Clara married John Hay when she was 24. Flora devoted the decade between her high school graduation and marriage to her temperance and day nursery work.

The College for Women gave Flora her long-delayed chance to go to college. Even though she was a wife and the mother of four young children, with a demanding social and civic life, she visited the college almost every day, getting to know the students and bringing gifts or visiting lecturers. She invited the graduating class to her home every spring. [49] And sometimes as a guest, sometimes as a hostess, she, and often Samuel, attended formal parties, dances, and receptions at the college. She also served on its Advisory Committee.

In 1907, she and Clara donated a chapel to Adelbert College, a memorial to their father’s memory and a commemoration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the college’s move to Cleveland that he had engineered. Amasa Stone Chapel was completed in 1911, two years after Flora’s death.

On January 21, 1909, students from both the College for Women and Adelbert College lined Euclid Avenue to pay tribute to Flora as her funeral procession passed the campus on its way to Lakeview Cemetery. Although during her lifetime, she did not permit the name change, in 1931, the College for Women became Flora Stone Mather College, acknowledging her gifts of time, energy, and money. (She had also rejected the suggestion that Hathaway Brown School, another beneficiary of her generosity, be named after her.[50])

Amasa Stone had built a high school for his daughters, the Cleveland Academy, and a college named after his son Adelbert. Flora (and Samuel) not only gave generously to Adelbert College but helped to assure the survival of the controversial young college for women. Adelbert and Flora Stone Mather Colleges, perhaps the only coordinate colleges in the country named after siblings, were consolidated in 1971, along with Cleveland College. The three were renamed Western Reserve College in 1973 after the merger with Case Institute of Technology that produced Case Western Reserve University. [51] Flora’s name lives on in the Flora Stone Mather Center for Women at the university, which provides services and advocacy for women students and faculty.

After her death, Samuel – who himself had missed out on college – continued her tradition of giving to the university. He and his children gave the Flora Stone Mather Memorial Building in 1914, and in 1930, a $500,000 addition to the building. [52] Samuel also donated $400,000 to the university in 1923 and made gifts to various programs within the university. [53]

Like her father, Flora donated to Lakeside Hospital, originally the Protestant Home for Friendless Strangers, during her life and at her death. [54] Samuel was also a major benefactor of the hospital, instrumental in its move to University Circle and serving as president and chairman of its board of trustees from 1899 to 1931. Mather Pavilion honors his memory. [55]

Other women have also given generously to Cleveland. Among them are Frances Payne Bolton and Elizabeth Severance Allen Prentiss. Like Flora, both women inherited and married money, and both became important public figures.

Prentiss (1865-1944) was the daughter of Louis H. Severance. Her first husband, Dr. Dudley P. Allen, was on the faculty of the Western Reserve University Medical School; he died in 1915. She married industrialist Francis F. Prentiss in 1917. She donated the Allen Memorial Medical Library to Case Western Reserve University, made significant gifts to the Cleveland Museum of Art, and established the Elizabeth Severance Prentiss Foundation to promote medical research. In 1928, she also became the first woman to receive the Chamber of Commerce distinguished service medal. [56]

Bolton (1885-1977) was the daughter of banker-industrialist Charles W. Payne. Volunteer work with the Visiting Nurse Association in New York City inspired her interest in professional nursing, and she funded a school of nursing at Western Reserve University in 1923. This was named the Frances P. Bolton School of Nursing in 1935. In 1939, she finished the unexpired term in the U.S. House of Representatives of her late husband Chester Castle Bolton and held that office until 1968. [57]

Yet Flora stands out because of the breadth and depth of her commitment to the city and its people. She would be thrilled that her husband was named Cleveland’s “first citizen” for his role as founder and funder of its Community Chest, the forerunner of United Appeal, as well as for his leadership of many other organizations.[58] She would likely be embarrassed that in 2010, she and Samuel were named the second most influential people in the city’s history: their generous partnership has sustained Goodrich House, Western Reserve University, University Hospitals, and countless other significant institutions. [59]

Always the modest daughter, she properly acknowledged her debts to her heavenly and earthly fathers. Nevertheless, Flora became her own woman, creating a new path and new opportunities for herself and others.

[1] Quoted in Gladys Haddad, Flora Stone Mather: Daughter of Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue and Ohio’s Western Reserve (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2007), xi. I am deeply indebted to this sensitive portrait of Flora’s private life as daughter, wife, and mother. I have focused instead on her public life. I also want to apologize for referring to Flora Stone Mather by her first name, which I would never do if she were present. However, since her name changes from Flora Stone to Flora Stone Mather after her marriage in 1881, it seems easier – if somewhat disrespectful – to use “Flora” throughout this essay.

[2] Haddad, xi, 70.

[3] Quoted in Haddad, 10.

[4] Quoted in Haddad, 54.

[5] Haddad, 20.

[6] Haddad, vii, viii, 38-39.

[7] David V. Van Tassel and John G. Grabowski, Dictionary of Cleveland Biography (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1996), 309-10.

[8] C.H. Cramer, Case Western Reserve: A History of the University, 1826-1976 (Boston: Little, Brown & Company), 81-86.

[9] Haddad, 70-71.

[10] Haddad, 108-9.

[11] Michael J. McTighe, A Measure of Success: Protestants and Public Culture in Antebellum Cleveland (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 29.

[12] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 17, 1863: 3.

[13] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 28, 1866:3.

[14] In October, 1879, the great evangelists Dwight L. Moody and Ira D. Sankey preached to full houses at Old Stone; one sermon was on “The Work and Power of the Holy Spirit.”Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 9, 1879: 1; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 10, 1879: 4.

[15] Jeannette Tuve, Old Stone Church: In the Heart of the City Since 1820 (Virginia Beach, Virginia: Donning Company, 1994), 42.

[16] Marian J. Morton, “Temperance, Benevolence, and the City: The Cleveland Non-Partisan Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1874-1900,” Ohio History, Vol. 91, Annual 1982: 58-73.

[17] Cleveland Day Nursery Association, Mss. 3667, container l, folder 14, Western Reserve Historical Society (WRHS), Cleveland, Ohio. The temperance movement’s ultimate success, the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919, was opposed by Samuel Mather when in 1928, he joined the board of the Association against the Prohibition Amendment: Kathryn L. Makley, Samuel Mather: First Citizen of Cleveland (Minneapolis: Kathryn L. Makley, 2013), 46

[18] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27, 1876: 4.

[19] Mss. 3677, container 1, folder 14, WRHS.

[20] Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 18, 1880: 4.

[21] Quoted in Haddad, 31.

[22] Haddad, 75.

[23] Mss. 3667, container 1, folder 3, WRHS.

[24] Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 30, 1887: 2.

[25] Goodrich House, Mss.3505, container 5, folder 2, WRHS.

[26] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 7, 1897: 6.

[27] Mather Family Papers, Mss. 3735, container 8, folder 7, WRHS.

[28] Frederic C. Howe, Confessions of a Reformer (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1988), 76.

[29] John G. Grabowski, “Social Reform and Philanthropic Order in Cleveland, 1896-1920,” http://www.teachingcleveland.org.

[30] Mather Family Papers, Mss. 3735, container 8, folder 7, WRHS.

[31] Mss. 3735, container 8, folder l, WRHS.

[32] Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 18, 1900: 1.

[33] Marian J. Morton, Women in Cleveland: An Illustrated History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana State University Press, 1995), 42-43.

[34] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 7, 1905: 33.

[35] Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 11, 1901: 10.

[36] Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1905: 6.

[37] Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1904: 12.

[38] Consumers League of Ohio, Mss 4933, container 1, folder 26, WRHS.

[39] Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 13, 1905: 4.

[40] Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 5, 1908: 7.

[41] C.H. Cramer, Case Western Reserve: A History of the University, 1826-1976 (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1976), 78-86.

[42] Cramer, 85.

[43] Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 3, 1889: 8.

[44] Cramer, 89-98.

[45] Cramer, 100-102.

[46] Cramer, 102; Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 23, 1891:8.

[47] Cramer, 103.

[48] Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 20, 1898: 5.

[49] Cramer, 103.

[50] Haddad, 87.

[51] Richard E. Baznik, Beyond the Fence: A Social History of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University, 2014), 355.

[52] Haddad, 109.

[53] Baznik, 86.

[54] Haddad, 79-80, 108.

[55] David D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 1034.

[56] Van Tassel and Grabowski, Dictionary of Cleveland Biography (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 359.

[57] Van Tassel and Grabowski, Dictionary, 53.

[58] Makley, 25.

[59] Plain Dealer, December 26, 2010: H2.

“The President From Canton” by Grant Segall

William McKinley

THE PRESIDENT FROM CANTON

by Grant Segall

Greeting the nation from his front porch in Canton, nursing his frail wife, sporting scarlet carnations from a foe, soft-peddling his views, the dapper little William McKinley seemed like the quintessential Victorian. The impression deepened when assassin Leon Czolgosz from Cleveland froze him in time and Teddy Roosevelt rough-rode into the Progressive era.

But McKinley launched what became known as the American Century. He helped make a former colony a colonizer and the world’s biggest manufacturer. He planned the Panama Canal and the Open Door policy toward China. He promoted labor rights, mediation and arbitration. He created the White House’s war room, press briefings and press receptions.

He also started a century-long rise in presidential power. Future President Woodrow Wilson wrote in 1900, “The president of the United States is now, as of course, at the front of affairs, as no president, except Lincoln, has been since the first quarter of the 19th century.”

McKinley broadened a Republican base that mostly dominated until 1932. While he quaintly campaigned from his porch, innovative backers paid the way of an estimated 750,000 visitors from around the country. They also used early polls and movies.

Historian Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University once told The Plain Dealer, “McKinley was the first modern president.”

Biographer Kevin Phillips wrote, “The Progressive era is said to begin with Teddy Roosevelt, when in fact McKinley put in place the political organization, the antimachine spirit, the critical party realignment, the cadre of skilled GOP statesmen…, the firm commitment to popular and economic democracy and the leadership needed.”

Supporters called him the Idol of Ohio. Critics called him Wobbly Willie. Republican boss Tom Platt of New York thought the Ohioan “much too amiable and much too impressionable.” Joseph Cannon, future House speaker, said McKinley kept his ear so close to the ground, grasshoppers jumped inside.

McKinley was hard to gauge. He wrote little, spoke calmly and wore mild expressions. But colleagues saw a master behind the mask. Fellow Congressman Robert LaFollette, future Wisconsin governor and senator, said, “Back of his courteous and affable manner was a firmness that never yielded conviction, and while scarcely seeming to force issues, he usually achieved exactly what he sought.” Elihu Root, McKinley’s war secretary, later Nobelist and senator, said the president would “bring about an agreement exactly along the lines of his own original ideas while [Cabinet] members thought the ideas were theirs.”

Most modern historians agree. Quentin R. Skrabec wrote, “It might be argued that McKinley’s behind the scenes approach was more effective than Roosevelt’s headlines.”

McKinley avoided serious scandals. He refused speaking fees and corporate jobs while in Congress. He shunned endorsements that required patronage.

Some editorial cartoonists drew him as a puppet of Cleveland ally Marcus Alonzo Hanna, dubbed “Marcus Aurelius” or “Dollar Mark.” In 1893, when the economy tumbled, Hanna and fellow tycoons paid off a $130,000 debt that McKinley had incurred backing a friend’s business. Critics sneered, but most of the public sympathized.

While chief executive, McKinley said, “I have never been in doubt since I was old enough to think intelligently that I would someday be made president.”

McKinley was the sixth elected Republican president in a row born a Buckeye. He was born Jan. 29, 1843, the seventh of eight children in a Scotch-Irish, Whig, abolitionist family. He was raised in the northeastern Ohio towns of Niles, Poland and Canton. His father, William Sr., managed and co-owned an iron foundry. Historians say McKinley grew up to promote the local kind of capitalism: small, independent, businesses with good products, good wages and good returns.

He went to a Methodist academy and was baptized. He entered Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., but soon came home ill and grew depressed. He clerked for the postal service and taught school.

When the Civil War broke out, McKinley enlisted. At Antietam, he insisted on delivering food and coffee through cannon fire. He rose to brevet major and served closely with future leaders like Rutherford B. Hayes. He would become the last of several Civil War veterans in the White House, where he’d go by “Major,” not “Mr. President.”

In peacetime, McKinley spent a year at Albany Law School and started a practice in Canton. Soon he became a Mason, local YMCA president and Stark County Republican county chairman. He was elected county prosecutor in 1869 and narrowly defeated in 1871.

He fell in love with a rare female bank cashier: the slim, blue-eyed, curly-haired Ida Saxton, whose leading family owned the bank and the Repository, a Republican-minded newspaper. The couple married in 1871, when she was 23 and he nearly 28, old for newlyweds back then. They rented two modest houses in turn from her family before finally buying one in 1900. The other is now called the Saxton-McKinley House, part of the National First Ladies Historic Site.

The couple’s two girls died young. The grieving mother developed seizures and became an invalid for the rest of her life. William took to reading the Bible and playing cars with her for a couple hours per day.

In 1876, miners were arrested for rioting in nearby Massillon. McKinley defended them for free. Just one was convicted. The lawyer’s success turned a foe, mine owner Hanna, into a supporter.

That year, at age 34, McKinley won election to Congress. Over the next 14 years, Democrats tried to gerrymander him out of office whenever they could. He lost in 1882 but retook the seat in 1884. One opponent always gave him a carnation to wear for their debates. McKinley wore the seemingly lucky flower for life.

The congressman championed tariffs to boost domestic goods and wages. He backed the Interstate Commerce Act and the Sherman Antitrust Act. On one of the era’s hottest issues, he supported “sound money” standards of gold and sometimes silver too.

In 1888, he was wooed for the presidential nomination but kept a pledge to support Ohio Senator John Sherman. In 1890, he narrowly lost a bid for speaker of the House but began to chair the powerful Ways and Means Committee.

That year, he passed the McKinley Tariff, raising rates on most imports to a record 48 percent, but conceding some breaks for special interests. The Democrats gerrymandered his seat again, and phony peddlers offered goods at daunting prices blamed on tariffs. He lost by 300 votes, but won the governorship in 1891 and again in 1893.

He persuaded the Statehouse to tax railroads, telegraphs, telephone lines and foreign corporations. He won a labor arbitration board and fines for bosses who fired unionists. He promoted workplace safety, led a relief drive for starving miners and successfully mediated a railroad strike. He also sent the National Guard to quell a violent strike.

McKinley reportedly waved to Ida every morning from the spot outside the Statehouse where his statue now stands, then waved again every afternoon from a window. She tried to attend official events but often had fits during them. He calmly covered her face with a handkerchief or carried her from the room.

In 1892, he refused presidential consideration again but finished third at the convention anyway. In 1894, he stumped in 300 cities for Republicans. The next year, he declined renomination as governor and took quiet aim at the White House.

By tradition, he stayed home during the 1896 convention. He won on the first ballot, with 661 1⁄2 votes to 84 1⁄2 for his nearest rival. The vice-presidential nominee was Garret Hobart, head of the New Jersey state senate.

As Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland prepared to step down, William Jennings Bryan swept the Democratic and Populist nominations with his “cross of gold” demand for free and unlimited currency. Then he stumped over 18,000 miles and seemed to surge.

McKinley kept to his porch meanwhile. “I might just as well put a trapeze on my front lawn… as go out speaking against Bryan,” he reportedly said. “I have to think when I speak.”

But his homey campaign was hardly homespun. Like James Garfield in Mentor 16 years earlier, he gave well-scripted greetings that newspapers spread afar. He campaigned for a “full dinner pail.” He said, “It is a good deal better to open up the mills of the United States to the labor of America than to open up the mints of the United States to the silver of the world.”

Hanna billed him as an “advance agent of prosperity.” The tycoon deployed some 1,400 speakers and 200 million pamphlets in a nation of just 14 million voters. He raised a war chest estimated anywhere from $3.5 million to $10 million, which would be worth about $269 million in 2014 dollars. The bounty included $250,000 from John D. Rockefeller, Hanna’s schoolmate at Cleveland’s Central High School.

Bryan’s polemics—rural, nativist, fundamentalist and classist—eventually turned many previously Democratic workers in the swelling cities toward moderate, inclusive McKinley. The Republican got 271 electoral votes to 176 and 51.0% of the popular votes—the first presidential majority in 24 years.

Taking office on March 4, McKinley called a special session of Congress and won the highest tariffs yet. Soon the economy began to surge. In 1898, for the first time, the U.S. would export more manufactured goods than it imported.

Meanwhile, McKinley stripped civil service protections from about 4,000 jobs. His first cabinet picks were weak, and six of the eight fell out during the first term. But his choice of an aging John Sherman for secretary of state opened up a Senate seat for Hanna.

The president appointed some black officials and pushed recruitment and promotion of black troops, but did little else to stop the nation’s rising discrimination. He visited the Tuskegee Institute and Confederate memorials. He denounced lynching but did little to stop it.

McKinley telegraphed, telephoned and traveled widely. He became the first president to visit California. Death stopped his plans to be the first abroad, but he’d already crossed borders in other ways. He helped pass the Hague Convention on warfare and create the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration. He helped crush China’s Boxer Rebellion and launch the Open Door policy to help U.S. exports there. He sent Marines to Nicaragua to defend Americans’ property.

In 1898, journalists and “imperialists”—a positive word at first—urged McKinley to free Cuba from a brutal Spain. McKinley balked. “I have been through one war; I have seen the dead piled up; and I do not want to see another.”

Then the Maine sank off Havana, and Navy officials blamed a probably innocent Spain. McKinley led what Secretary of State John Hay of Cleveland famously called “a splendid little war.” The president directed the troops in some detail. He won wartime taxes on high inheritances and more. He also persuaded Congress to annex Hawaii.

The war took just four months. Spain agreed to free Cuba and cede Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the U.S. The Senate narrowly accepted the territories, and U.S. troops spent four years quelling Filipino insurgents.

Unlike most predecessors, McKinley stumped for congressional candidates in mid-term. The Republicans kept control of both houses.

He sought treaties on dual standards for currency, but gold strikes were undercutting silver. In 1900, he signed the Gold Standard Actwith a gold pen.

At the 1900 Republican convention, the only question was who’d replace the late Hobart as vice president. Hanna lobbied hard against Roosevelt, but McKinley refused to interfere, and the New Yorker prevailed.

Bryan was renominated by the Democrats and stumped widely again, as did Roosevelt. McKinley returned to his porch, and Hanna raised more millions. The incumbent’s victory was bigger than before: 292 to 155 in electoral votes; 51.7 percent to 45.5 percent in popular votes.

During his second term, he planned a commerce and labor department. He also told an aide, “The trust question has got to be taken up in earnest, and soon.” He’d already called trusts “dangerous conspiracies… obnoxious to common law and the public welfare.” But his attorneys said they lacked power against the trusts, and he proposed no stronger laws.

On Sept. 5, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, he said treaties to lower tariffs would help the nation’s growing industries. “We should sell anywhere we can and buy wherever the buying will enlarge our sales.”

Despite rising assassinations overseas, he insisted on shaking hands with strangers at the exposition the next day. “No one would wish to hurt me,” he said. A young girl reportedly asked for his lucky carnation. He complied. Then Czolgosz approached to act for anarchy. McKinley offered a hand. A bullet flew deflected off his coat button. Another lodged in his stomach.

The crowd grabbed Czolgosz. “Don’t let them hurt him,” McKinley murmured from a chair. He turned to his secretary, George Cortelyou: “My wife, Cortelyou, be careful how you tell her – oh, be careful!”

McKinley languished for eight days at a nearby house. Doctors spoke optimistically but missed the bullet and a case of gangrene. On the 13th, he said, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Ida cried and begged to go with him “We are all going; we are all going,” he replied. “God’s will be done, not ours.” He died early the next day.

Roosevelt took the oath and said, “It shall be my aim to continue absolutely unbroken the policy of President McKinley.” Czolgosz was promptly tried and electrocuted.

McKinley grew even more popular in death. Mourners put his likeness on the $500 bill, his name on the continent’s highest mountain and his coffin in a new memorial in Canton. They also made Ohio’s state flower the scarlet carnation.

McKinley’s reputation has weathered well. Biographer Kevin Phillips called him “an upright and effective president of the solid second rank.” H. Wayne Morgan wrote, “He was not a ‘great’ president, but he fulfilled an exacting and critical role with success and ability displayed by no other contemporary.”

For further reading:

William McKinley by Kevin Phillips, 2003, Henry Holt & Co.

The Presidency of William McKinley by Lewis L. Gould, 1980, University Press of Kansas.

William McKinley and His America by H. Wayne Morgan, 2003, Kent State University Press.

William McKinley and Our America by Richard L. McElroy, 1996, Stark County Historical Society.

Places to visit:

McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, 800 McKinley Monument Dr. NW, Canton, OH 44708, 330-455-7043, www.mckinleymuseum.org.

National First Ladies’ Library, 331 Market Ave. S., Canton, OH 44702, 330-452-0876, www.firstladies.org.

About the Author

Grant Segall has spent 39 years on daily newspapers, including 30 at The Plain Dealer. He currently writes the My Cleveland column and covers the Berea school district for the PD and Sun News. He has shared in three national prizes and won several state and regional ones.

Segall has freelanced for Time, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil has been published by Oxford University Press and by houses in Korea and China. His short stories have been published in college journals, including Whiskey Island at Cleveland State, and in independent zines. He lives in Shaker Heights and has three sons.

The Western Reserve’s Self-Made President By Grant Segall

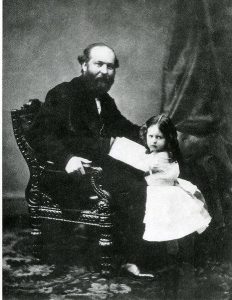

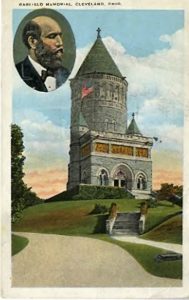

1) James A. Garfield at 16, 2) James A. Garfield with daughter Mollie in 1870, 3) Postcard of Garfield Monument at Lakeview Cemetary (All photos: Cleveland State Special Collections)

The Western Reserve’s Self-Made President

By Grant Segall

A delusional job-seeker and a backwards doctor ended one of Northeast Ohio’s most promising stories too soon.

James Abram Garfield was just 49 years old and not quite four months into the presidency when slain in 1881 by Charles J. Guiteau, a spurned supplicant trying to boost Garfield’s foes. It took Doctor (his real first name) Willard Bliss 79 more days to finish off the patient. Now we’ll never know what might have been accomplished by the second youngest president to that date and still the only one from the Western Reserve (the hopeful Mark Hanna, Newton D. Baker, Dick Celeste and Dennis Kucinich notwithstanding).

The self-made Garfield showed rare potential. He was the last person to rise from a log cabin to the White House. He’s still the only one to have gone there directly from the House of Representatives, although he was also a senator-elect at the time. During his swift career, he went from janitor to president of the future Hiram College, then to major general, House minority leader, long-shot presidential nominee and innovative front-porch campaigner. He never lost an election, even at college. A self-taught lawyer, he argued his first case in the nation’s highest court and won an important precedent. A polymath, he created a proof of the Pythagorean theorem that a journal published. He was such an exemplary Horatio Alger hero that Alger wrote his campaign biography.

But he also had plenty of flaws. He entered into conflicts of interest. He undercut a few superiors, sometimes while ostensibly supporting them. He joined a dubious partisan vote in 1876 that gave the White House to Rutherford “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes. He jilted a sweetheart and apparently cheated at least once on his wife. He zigzagged on some leading issues, including tariffs, Reconstruction, and civil service. He tried variously to appease and defy party bosses.

“Garfield,” former President U.S. Grant once wrote, “is not possessed of the backbone of an angleworm.”

Grant’s subject could be moody, touchy and self-righteous. He fumed in his diary about enemies: “barking hounds” with “vulture eyes” who launched “bitter and malignant assaults.” He sounded suspiciously innocent at times, as in “I am a poor hater” and “I am conscious of not being fitted for the partisan work of politics….” He could stretch the truth, as in “I have never asked anybody for a place.”

After he died, the nation memorialized him widely and moved on. In 1935, Novelist Thomas Wolfe called him one of the “lost presidents” of the late 1800s, already blurred by time. Garfield may have shaped his country more in death than life. His assassination clinched the case for civil service reforms and his mistreatment for medical ones.

His log cabin is gone, and his native Orange Township, too, but a replica cabin stands in what’s now Moreland Hills. The youngest of four surviving children, he was born on Nov. 19, 1831, and named James for a dead brother. His strong-willed mother, Eliza, later recalled that her biggest baby looked like a “red Irishman.”

Before James turned 2, his father died after bad medical care foreshadowing his son’s. Eliza said that the child learned to read at 3 at a local school and often escaped chores through books. When he was 10, she remarried. A year later, she fled with the children, shocking neighbors, provoking a divorce.

Garfield grew to a then-impressive 6 feet tall. He was sandy-haired, blue-eyed, and vigorous but clumsy. At 16, he left home despite Eliza’s pleas. He worked the Ohio and Erie Canal for six weeks and fell overboard 14 times. Not knowing how to swim, he had to be fished out. He came home sick and determined to work with his mind. He attended Geauga Academy in Chester Township and taught at a nearby school meanwhile.

Near age 20, he entered the fledgling Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, run by his childhood denomination, the Disciples of Christ. (The school would later be renamed Hiram College for its town.) Garfield worked his way through as a janitor, carpenter, teacher, and ordained minister, speaking and preaching eloquently around the area for faith, abolition, and more. “I love agitation and investigation and glory in defending unpopular truth against popular error.” he wrote in a letter.

He studied deeply and widely but also played: hunting, fishing, shooting billiards, drinking a little, and passing time with the ladies. He courted a woman and backed off rather late by the era’s standards. Then he spent several years courting the smart, serious Lucretia (Crete) Rudolph, a Hiram trustee’s daughter. The two declared their love but set no wedding date. “There is no delirium of passion nor overwhelming power of feeling that draws me to her irresistibly,” he told his diary. “I feel inclined to be cautious.”

At age 22, Garfield left his sweetheart behind and entered Williams College in Massachusetts. Charming his young Eastern classmates, he led a literary club and journal, crusaded against fraternities, joined the new Republican Party, and became class salutatorian.

He returned to the Eclectic and taught many subjects. He sheltered a runaway slave and tried to rescue two captured slaves, but the latter proved to be pranksters in blackface. After a year back at the school, he helped the faculty oust the president and won the helm over an older rival.

In 1858, he finally married Crete. They had seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood. The next year, while refusing to campaign, he let the party nominate him on the fourth ballot for state senator and secure his easy election in a Republican district. At age 28, Columbus’s youngest senator quickly became a leading speaker and draftsman. Trying to reconcile the North and the South, he spoke in Louisville and brought Kentucky and Tennessee lawmakers to Ohio. He also wrote reports on weights and measures, education, and geology, calling vainly for a state geological survey. Meanwhile, he studied law on his own and passed the bar exam.

During the Civil War, Garfield organized a regiment, beat greater forces in Kentucky, and galloped through fire at Chickamauga. He became chief of staff to Gen. William Rosencrans, who wrote that the aide was “ever active, prudent and sagacious… He possesses the energy and the instinct of a great commander.” But Garfield criticized his superior’s dilatory warfare in a letter to a higher-up that later leaked and drew blame for Rosecrans’ demotion.

At home, Garfield was a kind, playful father. But, during his war wanderings, he seems to have had at least one affair, according to biographer Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University. Garfield later wrote to Crete that “by your grand faith and truth and endurance, our love was saved and purified through the fiery ordeal of the years.”

While off at war, he was elected to the House of Representatives. He took his seat in late 1863 and served 17 years. He chaired committees on banking and appropriations, the Census, and military affairs. He strengthened the wartime draft. He helped to start the U.S. Geological Survey, doing for the nation what he’d failed to do for Ohio. He spurred what would become the Education Department. He supported “hard money” backed by gold. He opposed unions and wanted troops to break strikes. He opposed most federal relief and called cooperative farms “communism in disguise.” He docked the wages of his political appointees to print a campaign speech supporting civil service reform.

Outside the Capitol, Garfield joined the boards of the Smithsonian Institution, the historically black Hampton Institute, and his former schools, Hiram and Williams. After Lincoln’s slaying, the Congressman reportedly calmed a vengeful mob in New York City, declaring, “God reigns, and the government at Washington still lives.” He also practiced a little law. In “ex parte Milligan” of 1866, he defended Southern sympathizers in the U.S. Supreme Court on charges of treason and won lasting limits on the jurisdiction of military courts.

The early 1870s brought controversies. Garfield took $5,000 to help a company win a contract to pave D.C. streets. Also, despite his initial denial, he apparently held shares or options awhile in Credit Mobilier, linked to the federally funded transcontinental railroad, and made or borrowed some $300 from the company. He was denounced on the campaign trail but survived.

In 1869, Garfield built a brick home in D.C. In 1876, keeping up with gerrymandered borders, he bought a grassy farm on Euclid Avenue in Mentor that reporters would punningly call Lawnfield. Soon he added that handy front porch.

Also in 1876, Garfield became Republican minority leader. That year’s presidential election foreshadowed 2000’s. Hayes lost the popular vote, but a commission including Garfield voted along party lines to give him pivotal Southern electoral votes, including Florida’s. Garfield fought for some of the president’s goals and opposed others, including a ban on political campaigning for civil servants.

In 1880, U.S. Treasury Secretary John Sherman of Ohio endorsed Garfield for the federal Senate, effective the next year. State lawmakers, who chose senators back then, complied. In turn, Garfield promised to nominate Sherman for president.

With Hayes not seeking a second term, the leading Republican candidates were Maine’s strong-willed Congressman James G. Blaine of the so-called Half-Breed faction and former president U.S. Grant of the Stalwarts, led by New York’s domineering senators, the body-building, philandering Roscoe Conkling and his protege, the slight, philandering Thomas Platt. Politicians and reporters began calling Garfield a dark horse who might unite the party at its May convention in Chicago.

Garfield chaired the convention’s rules committee and thwarted a Stalwart demand for each state to vote as a bloc. Then he nominated Sherman with more praise for unity than for the candidate. On each ballot from the second through the 28th, Garfield got one or two votes. On the second day and the 34th ballot, he got 17. He objected to the votes but was overruled. He won handily on the 36th ballot, still the latest one in Republican history, and gave in.

His first challenge was to placate the Stalwarts, whose support was crucial, especially in New York. He picked a minion of theirs as a running mate: Chester A. Arthur, whom Hayes had dumped as customs collector of Manhattan’s port for doling out too many patronage jobs. In Garfield’s acceptance letter, he promised to consult local leaders about local appointments. Then he made a pilgrimage to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York to assuage Republican leaders there. Conkling checked in but skipped out before the meeting, perhaps to hide his hand in any deal. Afterwards, Garfield wrote in his diary “No serious mistake had been made and probably much good had been done. No trades, no shackles, and as well fitted for defeat or victory than ever.” Conkling resurfaced, claimed that Garfield had kowtowed, and condescended to stump for the ticket.

Back at Lawnfield, Garfield created the front-porch campaign, later perfected by William McKinley in Canton and Warren Harding in Marion. He spoke in English and German to more than 17,000 choreographed visitors, from President Grant to the Jubilee Singers of the historically black Fisk University. On view, he worked the farm and played horse with his sons. With a telegraph and two secretaries, he oversaw the campaign nationwide.

Supporters of the Democratic nominee, General Winfield Scott Hancock of New York, resurrected some controversies and invented others, including a forged letter in which Garfield supposedly called for unrestricted Chinese immigration. In the end, Garfield won by less than 0.1 percent of the popular vote but with a more comfortable 214 of 369 electoral votes, including New York’s.

Between victory and assassination, Garfield’s toughest challenges were appointments. He chose “Ben Hur” novelist Lew Wallace for ambassador to Turkey and poet James Russell Lowell for London. He outraged the Stalwarts by picking Blaine as secretary of state. He tried vainly to mollify them with Isaac MacVeagh from a Pennsylvania Stalwart family as attorney general and New York Postmaster Thomas James as postmaster general. At his hotel the night before the inauguration, Garfield was hastily revising his address when Conkling stormed into the room with Platt and Arthur to blast the proposed cabinet. Garfield listened in near silence.

For months, the president remained trapped between the Stalwarts, the meddlesome Blaine and the Democrats. Nominations were withdrawn, resignations threatened, maneuvers executed, and a filibuster thwarted. Garfield gave Arthur’s old port job to Judge Wililam Robertson, a leading Half-Breed. An outraged vice president gave his boss the silent treatment for a month but said plenty to the New York Herald, such as, “Garfield has not been square, nor honorable, nor truthful.” The president barred him from the White House for a while.

In other matters, Garfield supported a probe by the surprisingly independent-minded James and MacVeagh of postal graft by Republicans, including Garfield’s campaign manager. He refinanced war debts from 6 percent interest to 3.5 percent, saving more than $10 million per year, or more than 3 percent of the federal budget. He signed the Treaty of Washington, which called for arbitration of Civil War damage claims against Britain and renewed fishing agreements with Canada. He and Blaine offered to mediate disputes between other countries in our hemisphere. They also planned a Pan-American conference that President Arthur would scrap.

The Stalwarts finally imploded. Conkling and Platt quit the Senate to protest Garfield’s appointments. They presumed re-election in Albany, but the Half-Breeds promptly caught Platt in bed with a woman not his wife, and the legislature turned elsewhere.

Garfield’s domestic life was more respectable. His mother lived at the White House and often rode the stairs in his arms. His wife caught malaria in swampy D.C. and recuperated on the shore in Elberon, N.J. Crowds kept streaming into a rather open White House in search of jobs. “Some civil service reform will come by necessity,” Garfield told his diary, “after the wearisome years of wasted Presidents have paved the way for it.”

No one was more wearisome than Guiteau, a self-taught lawyer, like Garfield, and a dropout from a polygamous commune. Guiteau hounded the White House, the State Department, even Garfield’s church, ranting during a service. He was often turned away but never arrested. He began to tote a pistol but balked twice at shooting the president. On July 2, he tracked Garfield to the Baltimore and Potomac depot. The president planned to join Crete, drop off two sons at Williams, get an honorary degree there, and summer at Lawnfield. This time, Guiteau found the nerve to fire.

“My God!” cried Garfield, lurching. “What is this?”

Guiteau fired again. “I am a Stalwart,” he declared, “and Arthur will be president.” One bullet grazed the victim’s arm. The other lodged in a vertebrae.

Doctor Bliss was summoned, and Garfield was carted back to the White House. Spurning a recent trend for antiseptic care, Bliss and chosen associates repeatedly probed Garfield’s wounds with unwashed hands and tools. Alexander Graham Bell brought an invention to find the hidden bullet but failed. For weeks, the patient was feverish, nauseous and underfed, losing some 100 pounds. The doctors barred him to most of his colleagues, and the administration largely idled.

Garfield finally insisted on a trip to the Jersey shore. He died there on Sept. 19. A train draped in black took his body to Cleveland’s Public Square. There 150,000 people, about equal to the city’s population, paid their respects.

On trial, Guiteau blamed Garfield’s death on the doctors. He was convicted and hung, but medical experts agree with him today. He fulfilled his goal with Arthur’s reign. But the ascendant, tainted by a killer’s support and secretly dying from a kidney disease, promoted the Pendleton Act of 1883, which created civil service jobs, tests and protections.

Meanwhile, friends raised funds to support Garfield’s survivors, build the Garfield Monument at Lake View Cemetery, turn Lawnfield into a shrine, and create the first presidential memorial library there. Crete finished raising impressive children, including a Williams president and a U.S interior secretary. She died near the then-impressive age of 86.

In the “American Presidents” series, Ira Rutkow gives Garfield tepid reviews: “Garfield was not a natural leader and did not dominate men or events…”

In “Garfield,” Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University says that the Mentor man’s “stormy presidency was brief and, in some respects, unfortunate, but he did leave the office stronger than he found it.” He also says Garfield and Blaine “forged the Republican Party into the instrument that would lead the United States into the twentieth century.”

Kenneth D. Ackerman, author of “Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield,” told The Plain Dealer in 2006 that Garfield grew during his short reign. “He could have become a much stronger, much more effective president if he’d had the chance. Unfortunately, we’ll never know.”

For further reading:

“Garfield,” Allan Peskin, Kent State University, 1978, 1999.

“Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield,” Kenneth D. Ackerman, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003.

Places to visit:

The Garfield Monument, open daily, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., April 1 to November 19, Lakeview Cemetery, 12316 Euclid Ave., Cleveland (or enter at Mayfield and Kenilworth Roads, Cleveland Heights), 216-421-2665, lakeviewcemetery.com.

Garfield’s replica childhood cabin, open 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturdays, Moreland Hills village campus, 4350 SOM Center Rd. Photos and memorabilia are also displayed at the hall, open 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays. See morelandhills.com/moreland-hills-historical-society/the-james-a-garfield-memorial-cabin.

About the Author

Grant Segall has spent 39 years on daily newspapers, including 30 at The Plain Dealer. He currently writes the My Cleveland column and covers the Berea school district for the PD and Sun News. He has shared in three national prizes and won several state and regional ones.

Segall has freelanced for Time, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil has been published by Oxford University Press and by houses in Korea and China. His short stories have been published in college journals, including Whiskey Island at Cleveland State, and in independent zines. He lives in Shaker Heights and has three sons.