UTILITY VERSUS INNOVATION

A POLEMIC ON ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND CULTURAL CONSERVATISM IN CLEVELAND

by Steven Litt

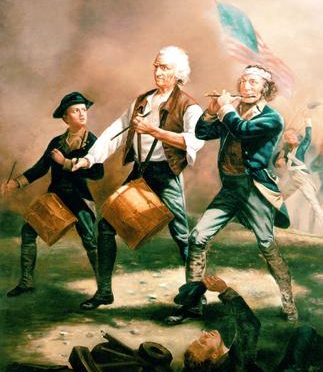

Archibald Willard had no way of knowing it at the time, but when he completed his eight-by-ten foot painting, The Spirit of ’76 for the 1876 Centennial celebration in Philadelphia, he launched what would become the single most famous artistic image produced in Cleveland in the city’s history. Reproduced and copied, celebrated or lampooned in illustrations, cartoons, or parodies by other artists, Willard’s brainchild entered the national mainstream in the 19th century a manner that anticipated Norman Rockwell’s highly popular magazine covers for Saturday Evening Post in the mid 20th century.

Based on memories of a parade witnessed by the artist when he was a child, Willard painted two grizzled men playing the part of veterans of the War of Independence, marching alongside a young boy in a Revolutionary War outfit. While the image is famous, it is less widely known that it originated in Cleveland and arose out of purely commercial impulses. The concept grew out of a commission from publisher James F. Ryder, who realized that the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1876 represented a fantastic opportunity to sell chromolithographs as patriotic souvenirs in Philadelphia, the site of a major national celebration.

In 1875, Ryder recruited Willard, then supporting himself as a carriage painter and a part-time maker of fine-art easel paintings in rural Wellington, Ohio, to move to Cleveland to work on the assignment. Following the success of the lithograph and the original painting, Willard spent the rest of his career creating subsequent versions, one of which now hangs in Cleveland’s City Hall, where an adjacent park at the northwest corner of Lakeside Avenue and East Ninth Street bears the artist’s name.

The success of Willard’s painting, described in detail in the catalog of a 1996 exhibition on the history of Cleveland art at the Cleveland Museum of Art, would appear to be little more than an odd historical footnote. From a larger perspective, however, its prominence is not accidental. It embodies the practical, moneymaking role often assigned to artists in Cleveland, an industrial city in which art has often been closely linked to commerce. The Cleveland Institute of Art, the city’s four-year independent art college, crystallized this utilitarian, business-oriented view of art memorably in its catchy, longtime motto: “Making Art Work.” Embedded in the motto is the notion that Cleveland is a place where no one should be squeamish about exploring connections between creativity and commerce. The motto also conveys a fundamental skepticism about the value of art for art’s sake, or about art as a way to express innovative new ideas. In other words, the motto is unintentionally revealing as a description of less than positive aspects of the city’s artistic and intellectual climate.

Today, public and private philanthropic support for the arts in Cleveland is stronger than ever, and the arts are being called upon to perform a truly big job: to help revive the city’s struggling economy and to make it a more attractive place to live. The question arts supporters and audience members should be asking is whether success in the arts should be evaluated primarily in quantitative economic terms, or according to the more subjective, qualitative benchmarks such as quality, originality, and critical and scholarly esteem. Put in a different way, if economic impact is the primary measure of artistic success and importance, we can all be proud of Archibald Willard and his Spirit of ’76. If, on the other hand, artistic quality is the truer measure of the impact of a city’s cultural contributions, it should be cause for at least mild concern that the author of the most famous artistic image in the city’s history is an obscure 19th-century painter whose work borders on kitsch and whose name is all but forgotten outside Cleveland.

Such concerns are worth discussing, now that the arts are being asked to play a bigger role than ever in the city’s economy. Cleveland’s urban predicament as a shrinking industrial city in a troubled region is widely known. Its population is hovering just over 400,000, roughly sixty percent lower than it was in 1950. The old industrial base is fading rapidly, but new industries, such as health care and biotechnology, are not growing fast enough to reverse decline. Decades-old tensions over race and poverty have caused an exodus of middle-class residents, both black and white. Meanwhile, low-density residential subdivisions in the suburbs consume more and more open land every year, creating a pattern of sprawl without growth.

Within this urban context, the arts, measured by activity levels at major and minor institutions, are certainly working hard. The cultural calendar in Cleveland is packed; venues across the city offer a range and quantity of plays, concerts, exhibitions, and recitals that far exceeds what one might expect for a metropolitan area of Cleveland’s size. Cleveland still compares well in cultural terms with fast-growing cities in states such as Florida, Arizona, Texas, and California. For example, the Cleveland Museum of Art ranks as one of the top 10 institutions of its kind, as measured by endowment wealth. The Cleveland Orchestra is regularly touted as one of the top five in the nation. Playhouse Square, which draws a million visitors a year to Broadway touring shows and local productions, is the second largest unified arts complex in the nation after Lincoln Center in New York. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum steadily attracts a half million visitors a year.

Financial support for the arts in Cleveland is at an all-time high. Evidence of this enthusiastic backing includes the Cleveland Museum of Art’s ongoing $350 million expansion and renovation, described as the largest single cultural project in Ohio history. Other indicators include the 10-year, 1.5 cents per cigarette tax approved by Cuyahoga County voters in 2006 to create a $15 million annual fund to support arts and culture. The fund is the first of its kind in county history. Across the city, developers and planners tout local arts districts as key tools in the fight to preserve struggling neighborhoods. What’s problematic here is that arts funding is based primarily on a utilitarian view of cultural activity as a lifestyle amenity and as a generator of economic activity, not as an expression of the city’s ability to foster original creative thinking of global significance.

Artists and architects in Cleveland rarely attract much notice outside the city. In architecture, local firms rarely win the biggest and most prestigious assignments. Instead, clients prefer to hire prestigious out-of-town firms, which often do less than their best in Cleveland. In painting and sculpture, most of the most famous artists associated with the city have left to pursue their ambitions elsewhere, a telling example of a creative brain drain.

In this context, it’s haunting to consider that Cleveland’s conservative views on the arts have at least until now paralleled the city’s economic decline. This doesn’t necessarily mean that, if Cleveland had been a hotbed of artistic radicalism throughout the past century, it would be in far better economic shape today. But it is true that throughout history, artistic breakthroughs have occurred most often in vibrant and growing cities where innovation and originality in the arts are related to breakthroughs in business, science, and technology. This makes it worth considering whether new and different approaches to the arts could help reverse Cleveland’s decline by making it a place more open to fresh and innovative ideas it has traditionally disregarded or even shunned.

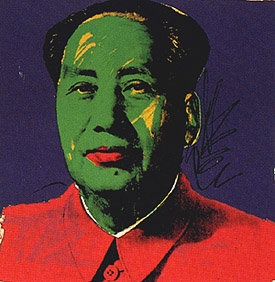

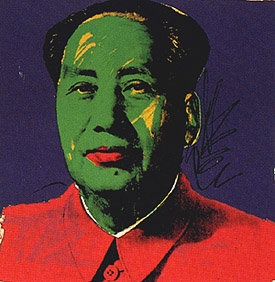

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of Progressive Corp. in Mayfield. Starting in the 1980s, Lewis built one of the largest and most dynamic corporate collections of contemporary art in the country. Curated for more than 20 years by his ex-wife and friend, Toby Lewis, the collection had the explicit goal of dynamic intellectual climate in the workplace as a way to challenge complacency among employees. The Lewises hung multi-colored portraits of Mao Zedong by Andy Warhol in the boardroom. They displayed a racially charged painting by the black Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall outside a cafeteria. Elaborate chandeliers made of dripped wax, by Petah Coyne, graced a stairwell.

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of Progressive Corp. in Mayfield. Starting in the 1980s, Lewis built one of the largest and most dynamic corporate collections of contemporary art in the country. Curated for more than 20 years by his ex-wife and friend, Toby Lewis, the collection had the explicit goal of dynamic intellectual climate in the workplace as a way to challenge complacency among employees. The Lewises hung multi-colored portraits of Mao Zedong by Andy Warhol in the boardroom. They displayed a racially charged painting by the black Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall outside a cafeteria. Elaborate chandeliers made of dripped wax, by Petah Coyne, graced a stairwell.

The idea was to irritate, provoke and remind employees that they lived in a world of constant change, and that they had better grapple with it. The ultimate goal, of course, was to make Progressive a stronger company. Apparently, it worked. While building the collection, Lewis also guided Progressive’s growth from a tiny company with 100 employees in the mid-1960s to its current ranking as the nation’s third largest auto insurer, with 26,000 employees. Lewis also made himself a billionaire in the process. The company’s success certainly derives from as much from Lewis’s leadership and management practices, but cutting-edge art is a strong part of the corporate culture. It could be argued that Lewis’s use of art as a motivational tool is a utilitarian approach to art, but what makes it different from the norm in Cleveland is its profound emphasis on embracing innovation, change, and new ideas.

As the Lewis example shows, a “progressive” approach to culture just might change the city’s traditionally conservative mindset. There’s ample room for similar efforts. These could include rebuilding the region as a center for industrial and product design, based on the rich legacy of creativity left behind by the greatest visual thinker in the city’s history, industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost. Equally important would be a revolution in the city’s architectural and urban design culture, signaled by improvements in the design of buildings, streets, parks, and public places of all kinds. The Cleveland Museum of Art, whose conservative tastes have had a chilling effect on the city’s artistic community, could take a bolder approach. Greater financial support could flow to the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, which has done an outstanding if under-appreciated job of championing the cause of progressive thinking in the visual arts.

THE ROOTS OF CONSERVATISM

Before considering the city’s future, it’s important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of its legacy in the visual arts. Cleveland has certainly played a role in the history of modern and contemporary art and architecture, but not a big one, and it’s important to understand why. The 20th century unleashed a concatenation of new ideas, movements, and artistic breakthroughs across Europe, but emanating primarily in the early decades from Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and other cities. These ideas, ranging from a plethora of art movements such as Cubism and Fauvism, to modernist architecture and design, were introduced to America first in the New York Armory Show of 1913, and the Museum of Modern Art’s first exhibition on modern architecture, in 1932. Following the Depression and World War II, New York replaced Paris as the global center of the art world. Modernist architecture spread across the country, producing vibrant results, especially in Los Angeles and Chicago, but also in New York, Detroit, Philadelphia, and other cities. The same was not as true in Cleveland.

While it’s obvious that Cleveland has had a fairly conservative artistic climate for decades, scholarly work on local art history is fairly thin, which indicates a lack of interest among art historians—a negative comment in and of itself. There exists no large, single-volume historical survey providing a broad overview of local developments in the visual arts in Cleveland and relating them to political, social, and economic trends. Nor does there exist any large study relating the city’s creative output with that of other cities in America and Europe. Such a study would create a clearer understanding of the place Cleveland truly occupies as an artistic and cultural center.

Mostly, the city’s art history is revealed through narrowly focused monographic books on individual artists. The Cleveland Artists Foundation, a small non-profit organization devoted to the visual arts of Northeast Ohio, has published many of these studies.

Though valuable, they don’t provide the bigger picture. The Cleveland Museum of Art attempted a larger overview in 1996 with its exhibition Transformations in Cleveland Art, 1796–1946. Valuable as it was, the exhibition only covered the first 150 years of the city’s artistic history, leaving the rest of the story for a future show. Organized by curators David Steinberg and William H. Robinson, the 1996 exhibition was accompanied by a catalog with an essay that said, “almost nothing has been written about how economic, social, and political events affected the character of Cleveland art.”

Nevertheless, historical and anecdotal information suggests strongly that the city’s cultural conservatism has several roots. One is ethnic heritage. After its initial settlement in the early 19th century, Cleveland’s population grew quickly as waves of immigrants arrived from New England and, later, from countries across Europe. Often, immigrant communities wanted to preserve traditions from their homelands. “Whatever was brought over in the late 19th century stayed that way,” scholar Holly Rarick Witchey, author of The Fine Arts in Cleveland told The Plain Dealer in an interview in 1996.“ When Greeks look for historical folk dances, they come to the U.S., where you are not allowed to innovate. You are preserving the homeland tradition.”

Elite taste also remained conservative throughout the city’s rise to industrial prominence, from 1890 to 1930, and in the decades following. For much of the city’s history, powerful backers of the arts were primarily members of the city’s wealthy and white Anglo-Saxon families. Members of this group included the Severances, the Hannas, and the Mathers. They and others were extremely interested in art and culture, and were extremely generous. Through donations and bequests, they built a large collection of cultural institutions in the early 20th century, starting with the Music School Settlement in 1912, Karamu and the Cleveland Play House in 1915, the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916, the Cleveland Orchestra in 1918, and the Cleveland Institute of Music in 1920.

The cultural largesse of the city’s leading industrial families was motivated by noblesse oblige, a desire to acculturate immigrants newly arrived from poor countries in central and Eastern Europe, and the impulse to compete in terms of prestige with other growing cities. Unlike arts patrons across the industrial Midwest, Cleveland’s wealthy appointed professional managers to guide major institutions, especially the museum and orchestra, to ensure high standards of performance and achievement. Even so, the museum, for example, largely pursued a conservative approach to art history, thereby honoring the tastes and preferences of trustees, who actively discouraged directors and curators from investing in modern and contemporary art.

CONSERVATISM AT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART

Conservatism in culture isn’t necessarily a negative value. In the best sense, it means conserving the finest expressions of the past, maintaining high standards of excellence, and focusing on appreciation of the best of the past, rather than exploring the more risky and unsettled field of contemporary art. In essence, this was the core philosophy of Sherman Lee, the highly influential director of the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1958 to 1983, a period in which the museum rose to international prominence but also gave short shrift to new art.

A serious, sober, deep-voiced authority with an imposing personal presence, Lee was considered during his tenure the opposite of the flamboyant director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Hoving, who first made popular the notion that art museums should cater to a broad public with blockbuster exhibitions and glamorous social events.

When Lee became the third director of the Cleveland museum in 1958, the institution received a massive bequest of $34 million from the estate of industrialist Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., worth roughly $250 million in 2010 dollars. The gift, the single largest in the museum’s history, made it for a time the wealthiest art museum in America, in terms of endowment wealth. Following his mission of conserving the best of the past for the future, Lee used the bequest systematically to build up the museum’s collection of European Old Master paintings, acquiring important works by Francisco Zurbaran, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Nicolas Poussin, Antonio Canova, and Jacques-Louis David. Simultaneously, he built a world-renowned collection of Asian art.

Meanwhile, the museum spent relatively little on modern and contemporary art made after the first decade of the 20th century. The museum assembled a strong collection of Blue, Rose, and Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso, but satisfied itself mainly with works of secondary importance by such important contemporaries as Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, or Jackson Pollock. To this day, the seminal art movements of the 1950s and ’60s, including Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, remain under-represented in the museum’s permanent collection, or are represented by works of secondary quality. Other significant gaps exist throughout the 20th-century collection, which is noticeably weaker than the museum’s highly respected holdings in everything from ancient Greek and Roman art, through Medieval European and Asian art to 19th-century American paintings.

Lee is often pigeonholed as an archenemy of new art, but his story is more complex. He realized in the 1960s and ’70s that prices for modern and contemporary art were rising, and he tried on occasion to persuade trustees to become more open-minded, but he faced heavy opposition. In an oral history interview after his retirement, he recalled a meeting with museum trustees in which he described how a Cubist painting by Picasso had enormously increased in value after the museum bought it. In response, a trustee jokingly shot back: “Sell!” In another instance, Lee recalled how a trustee donated a sculpture by Henri Matisse to the museum after having received the work as a gift from a friend.

The trustee thought so little of the bronze, which depicts a pair of lesbians embracing, that he used it as a doorstop. Such negative attitudes, made manifest subtly through art acquisitions and exhibitions that focused primarily on pre-modern art, communicated a powerful disdain for the 20th century and had a dampening effect on contemporary art in Cleveland. To counteract this tendency and provide encouragement to local artists, the museum started an annual series of juried exhibitions on Cleveland art in 1919, called the May Show, which stimulated the competitive spirits of local artists and inspired local collectors to acquire works selected for display. As popular as it was, however, the May Show failed to place local art in a broader national or international context and in that sense contributed to a prevailing sense of cultural isolation. The museum underscored the message by rarely exhibiting works it purchased from the May Show among other works in the collection. It wasn’t until the opening of the museum’s new East Wing in the summer of 2009 that it created special galleries dedicated to the art of Northeast Ohio.

The trustee thought so little of the bronze, which depicts a pair of lesbians embracing, that he used it as a doorstop. Such negative attitudes, made manifest subtly through art acquisitions and exhibitions that focused primarily on pre-modern art, communicated a powerful disdain for the 20th century and had a dampening effect on contemporary art in Cleveland. To counteract this tendency and provide encouragement to local artists, the museum started an annual series of juried exhibitions on Cleveland art in 1919, called the May Show, which stimulated the competitive spirits of local artists and inspired local collectors to acquire works selected for display. As popular as it was, however, the May Show failed to place local art in a broader national or international context and in that sense contributed to a prevailing sense of cultural isolation. The museum underscored the message by rarely exhibiting works it purchased from the May Show among other works in the collection. It wasn’t until the opening of the museum’s new East Wing in the summer of 2009 that it created special galleries dedicated to the art of Northeast Ohio.

Nevertheless, artists, collectors, and architects in Cleveland battled local orthodoxy and fought to introduce fresh ideas from abroad. Recent scholarship by William Robinson, the museum’s curator of Modern European Art, has shown that leading Cleveland artists in the 1910s, ’20s and ’30s, including William Sommer, Frederick Gottwald, August Biehle, and Carl Gaertner, drew direct inspiration from trips to Europe, particularly Germany. The post-Impressionist and Social Realist paintings work  of these “Cleveland School” artists is fascinating, in that it illuminates the history of Cleveland and evokes an extraordinary sense of place. A 1908 painting of a fire tug on the Cuyahoga River, painted by Biehle, exhibited in the 1996 exhibition on Cleveland art, conveys a sense of the smoke-shrouded Flats during the city’s industrial heyday in broad strokes of sooty browns and beiges. Gaertner’s 1926 Pie Wagon, purchased by the museum, shows steel workers gathered outside a soot-shrouded factory on a patch of blinding snow, eating snacks sold by vendors.

of these “Cleveland School” artists is fascinating, in that it illuminates the history of Cleveland and evokes an extraordinary sense of place. A 1908 painting of a fire tug on the Cuyahoga River, painted by Biehle, exhibited in the 1996 exhibition on Cleveland art, conveys a sense of the smoke-shrouded Flats during the city’s industrial heyday in broad strokes of sooty browns and beiges. Gaertner’s 1926 Pie Wagon, purchased by the museum, shows steel workers gathered outside a soot-shrouded factory on a patch of blinding snow, eating snacks sold by vendors.

Such paintings offer vivid impressions of the city’s industrial heyday. In purely artistic terms, however, they don’t qualify either Biehle or Gaertner as leaders of the 20th-century American vanguard. A powerful local exception was the immensely gifted Charles Burchfield, whose Expressionist-inspired landscape paintings throb with ecstatic energy. One of the most important American artists of the time, Burchfield left Cleveland for Buffalo in 1921 to support himself as a wallpaper designer, and later, starting in 1929, as a full-time painter. Cleveland can claim him only partially.

VIKTOR SCHRECKENGOST AND HIS LEGACY

By focusing primarily on the fine arts, the Cleveland museum’s 1996 exhibition inadvertently made the point that the most important artistic contributions from the city in the early to middle decades of the 20th century lay in ceramics and industrial design. Examples in the show included a silver tea and coffee service created by designer Louis Rorimer and an Art Deco decorative screen fashioned by Rose Iron Works. The best works in the show were a handful of ceramics produced by the great industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost, then still living.

In 2000, the museum gave Schreckengost the long overdue recognition he deserved with a major retrospective exhibition called Viktor Schreckengost and 20th Century Design. The show was incidentally the first major solo exhibition in the museum’s history devoted to a living Cleveland artist—another telling comment on the subtle disdain with which the museum had long viewed local art. Born in Sebring, Ohio, in 1906, Schreckengost was the son of a potter who worked at the French China Company. After studying at the Cleveland Institute of Art with leading Cleveland artists, such as Frank Wilcox and Paul Travis, he won a scholarship and attended the Vienna Kunstgewerbe School for a year, gaining direct exposure to one of the most artistically fertile cities in Europe. After returning to Cleveland, Schreckengost worked for Cowan Pottery and joined the faculty at the art institute, where he soon founded the Department of Industrial Design.

It was around this time that Schreckengost completed what may have been his most famous assignment. Without realizing who the client was, he created a design for a large punch bowl glazed in black and a rich faience blue, based on Art Deco themes related to jazz clubs in New York. Covered with images of skyscrapers, martini glasses, streetlights, stairs, and musical instruments, the bowl brims with the energy of Schreckengost’s upbeat personality. It was only after completing the assignment that he found out that the client was Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the then-governor of New York State and future president, FDR.

In his work as an industrial designer, Schreckengost combined artistic and functional brilliance in designs for everything from trucks to bicycles, furniture, industrial equipment and dinnerware. He invented the cab-over-engine truck, a design that enabled truck owners to carry more cargo, which allowed them to amortize their vehicles more quickly. During the Depression and the post-World War II period, Schreckengost’s designs stoked consumer desire and kept entire factories humming—a striking demonstration of “making art work.” Modest, pragmatic, and deeply concerned for the consumers of his highly affordable creations, Schreckengost showed that high artistic achievement could be unified with Cleveland’s commercial spirit.

Today, experts consider him one of the greatest American industrial designers of the 20th century, along with Russell Wright, Raymond Loewy, and Norman Bel Geddes, although Schreckengost is much less widely recognized than the others. He created enormous wealth for his corporate clients, but never sought the fame or riches that might have been his if he had moved to New York—as he was often urged to do during his lifetime. Instead, he remained in Cleveland throughout his 70-year career, teaching, designing useful objects, and making art in his free time. While teaching and designing for industrial clients, Schreckengost quietly produced hundreds of watercolors, ceramics, and sculptures in the sky-lighted attic studio of his home in Cleveland Heights. As an artist, his greatest achievement may have been Apocalypse ’42, a ceramic sculpture parodying fascist dictators of Germany, Italy, and Japan, now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Schreckengost’s impact on Cleveland’s and the nation’s economy has been profound. In addition to the direct effect of his designs on local and regional manufacturers, he educated generations of students at the art institute, many of whom achieved enormous success in their own right. Among them are Giuseppe Delena, a chief designer at Ford Motor Company; Joe Oros, designer of the Ford Mustang; and Jerry Hirschberg, head of Nissan Design International. Locally, former Schreckengost students John Nottingham and John Spirk founded a wildly successful industrial design company now headquartered in the renovated Christian Scientist Church overlooking Little Italy on the western edge of Cleveland Heights. Nottingham once estimated that more than 1,000 industrial designers studied with Schreckengost, collectively producing a huge impact on the national economy.

Today, Schreckengost’s work has inspired new initiatives aimed at reviving his legacy. The designer’s family has donated his extensive archive to Cleveland State University, and the city recently renamed East 17th Street “Viktor Schreckengost Way.” The university has donated storage and office space to a new for-profit venture, called American da Vinci, led by entrepreneur Wally Berry. The goal is to re-commercialize Schreckengost’s designs by licensing them to manufacturers. Profits will be shared with the university in the form of scholarships for students. The art institute has also partnered with the university to create the District of Design, a portion of downtown between PlayhouseSquare and the CSU campus, which will be devoted to showrooms for product designers and manufacturers in Northeast Ohio.

While Schreckengost’s designs were highly spirited and functional, they also reflected the inherent conservatism of Cleveland. They refined and adapted artistic and stylistic currents he absorbed from the leading movements and design theories of the 20th century. His aim always was to appeal to a broad public, which required that his designs be understandable and acceptable, not highly inventive in the development of entirely new forms. In other words, he thoroughly embodied the city’s pragmatic spirit, while also achieving a high standard of creative brilliance.

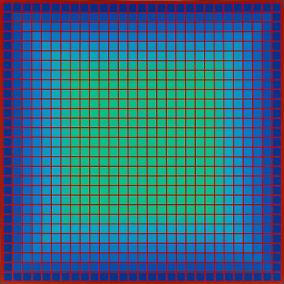

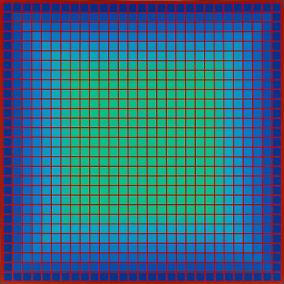

Other artists were not so fortunate; for them, Cleveland’s conservative climate has had an inhibiting, muffling effect; it led to an atmosphere that kept innovators on the fringe or forced them to leave the city to realize their visions elsewhere. It cannot be assumed, however, that Cleveland was devoid of globally significant moments of artistic innovation. For reasons that have yet to be thoroughly explored by scholars, the Cleveland Institute of Art became a haven in the early 1960s for artists who promoted the eye-tingling, high-precision patterns of Op Art.

Members of the group, including Ed Mieczkowski, Julian Stanczak, and Richard Anuskiewicz, earned international attention in 1965 when they showed their work in the important exhibition, The Responsive Eye, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Op Art was a short-lived trend, however.

Quickly condemned by critics as superficial and shallow, Op went out of favor. Stanczak and the other Ohio Op artists soldiered on quietly, producing paintings that have recently been rediscovered by collectors. Their works from the 1960s and ’70s now sell in the range of $50,000 to $100,000 at galleries in New York and Santa Fe, New Mexico. It’s a vindication, of sorts, but it also underscores how difficult it can be to build an artistic career in Cleveland.

THE LOCAL ART MARKET

Today, the art market in Cleveland remains relatively small; serious collectors do their most serious buying in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, or cities in Europe. An unofficial price ceiling of $5,000 to $10,000 for individual works of art ensures that artists who remain within the region will never achieve the financial success accorded leading artists in other cities. Today, the city lacks a central gallery district, which would facilitate comparisons among artists and instill a competitive creative climate.

Artists in the region often make a living by teaching at area universities, where the pay is low, tenure-track positions are rare, and many work in part-time jobs without health insurance. A strong negative synergy exists between the modest size of the local art market, the conservative nature of local taste, and the annual drain of talent. The list of important artists who left Cleveland over the 90 years because the city failed to provide optimal conditions for a successful career have included such luminaries as Charles Burchfield, Hughie Lee-Smith, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Mangold, Joseph Kosuth, Heidi Fasnacht, April Gornik, and Dana Schutz.

The stylistic and conceptual range represented by this loss of talent is enormous. In many cases, the artists involved knew that Cleveland would never provide the audience, market, and employment needed to achieve the highest success. Roy Lichtenstein, for example, graduated from Ohio State University in the late 1940s and spent close to a decade in Cleveland before moving to New Jersey to teach at Rutgers University. Soon, he was exhibiting at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York the comic-style Pop Art paintings that would make him famous around the world.

The story is a somber one. And yet, the rise of academia as a non-commercial support system for artists has created a certain stability, which enables many artists to persevere in the region. The bargain accepted by these artists is that they must teach in order to earn the studio time necessary to pursue their own work. More than a handful of local artists have built successful careers in this manner. Among them are the sculptor and painter Brinsley Tyrrell, painter Joseph O’Sickey, and glass artist Henry Halem, all affiliated with Kent State University. Cleveland State University has supported the careers of painter Ken Nevadomi and draftsman George Mauersberger. Case Western Reserve University has served as a base for the Pop-influenced painter and photo-collagist Chris Pekoc. The Cleveland Institute of Art provided the bedrock support needed by Stanczak to continue his exacting, precise, and highly rarefied Op Art explorations of color and form.

The decorative arts continue to be a particular point of strength in the Cleveland art scene. The Cleveland Institute of Art has enabled glass artist Brent Kee Young and ceramists Judith Salomon and William Brouillard to build careers of national significance in Cleveland. All are represented in major museum collections around the country. Jeweler John Paul Miller, who also taught for decades at the art institute, created a following among wealthy patrons in Cleveland, who acquired his exquisitely crafted gold jewelry. With its fusion of machine-like precision and natural forms based on insects and crustaceans, Miller’s work ranks among the best of its kind in the 20th century and is also very well represented in museum collections nationwide.

THE RISE OF LOCAL ARTS DISTRICTS

Every year, a trickle of new talent enters the Cleveland scene, as a percentage of art students graduating from local colleges and universities elect to stay in the city, motivated by the visual power of its industrial landscape, the richness of the best parts of the city’s artistic legacy, and the low cost of living. In recent years, city planners and community development officials have recognized that, when artists act as urban pioneers, property values rise, safety improves, and neighborhoods stabilize. The city has encouraged such settlement patterns in art districts in Tremont, Collinwood, St. Clair-Superior, and other neighborhoods.

The phenomenon is not unique to Cleveland nor is it new; it is fundamentally a reprise of the massive revival of real estate values in New York’s SoHo district. Starting in the 1960s and ‘70s, artists occupied vacant lofts in the cast iron industrial buildings south of Houston Street in Manhattan, which dated back to the Civil War era. By the 1980s, real estate values had surged to the point where artists and galleries were pushed out of the district by chic restaurants, hotels, boutiques, and stores for luxury furniture and lighting.

The artists and galleries decamped to Chelsea, the next Manhattan neighborhood to undergo transformation. Other cities around the country noted the phenomenon, and consciously tried to emulate it with public policies that encouraged artists to settle in formerly run-down areas. Economist Richard Florida boosted awareness of the positive economic impact of artistic activity in cities with his highly influential 2003 book, The Rise of the Creative Class. In it, he promoted the notion that high-tech workers are attracted to cities with strong physical and cultural amenities, where young, creative people feel at home. Businesses need to follow workers to such cities, not attempt to lure them to corporate cubicles in suburbs. In part based on Florida’s theories, foundations, developers and community development corporations are encouraging the formation of widely dispersed arts districts in Cleveland. On the surface, this would seem to be a positive trend. The danger is that the “peanut butter” approach of spreading resources thinly over a large city will prevent the coalescence of a central arts and gallery district. The enthusiasm for arts districts is also based on values that have nothing to do with the core purpose of art, which is the pursuit of quality, not the creation of “positive externalities” caused by the mere presence of artistic activity in a neighborhood. A sharp distinction needs to be made between the quality and merit of the artistic products coming out of neighborhood arts districts and the secondary economic benefits produced by the presence of artists in a community.

To date, the arts districts in Cleveland have certainly boosted real estate values and investment, and they’ve also contributed to striking advances in the quality of the city’s restaurants over the past 15 years. But while arts districts have made certain neighborhoods – including Tremont, Detroit-Shoreway, and Little Italy – better places to live, they haven’t sparked a true artistic renaissance.

CONSERVATISM IN CLEVELAND ARCHITECTURE

If the history of the fine arts in Cleveland is a mixed picture, the same is true of the city’s architectural history. Architecture gives enduring physical form to Cleveland’s cultural conservatism and shapes the city’s mind-set in countless ways, marking it as a place that imports and refines ideas developed elsewhere, not as a place of innovation in its own right.

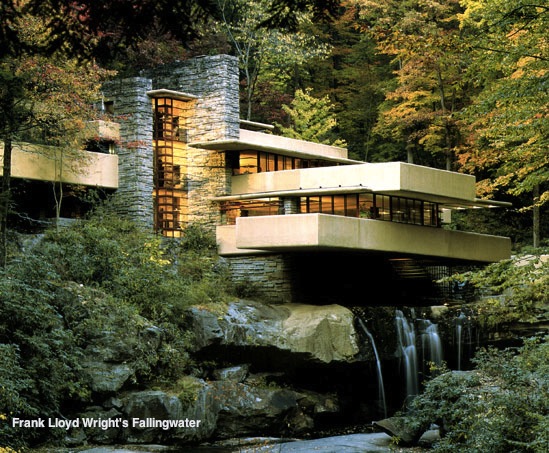

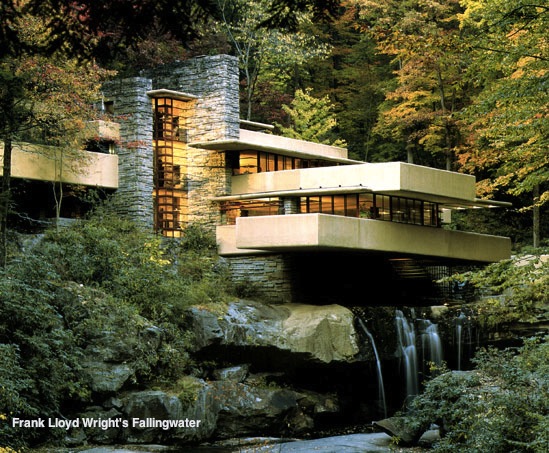

The irony is that during the first half of the 20th century, the Great Lakes industrial region was a global hot-bed of architectural creativity. Chicago architects such as Louis H. Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright launched modern architecture with nature-based theories of “Organic” design. After World War II, the great German modern architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, designed some of the most elegantly skeletal steel and glass buildings of his career in Chicago, including the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology. In Detroit, the Finnish-born Eliel Saarinen fused inspirations from Finnish vernacular design, Art Nouveau, and modernism in his masterpiece, the campus of Cranbrook in Bloomfield Hills. The architect’s son, Eero Saarinen, rocketed to fame in the 1950s and ’60s with the swooping forms of his TWA Terminal at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York. Although these architects were active throughout the region in Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and other cities around Cleveland, none ever received a single assignment in Cleveland.

In 1937, Wright designed his most famous work, Fallingwater, for the Pittsburgh department store magnate, Edgar Kaufmann, as a retreat in the Pennsylvania mountains east of the city. Wright did receive commissions in the Cleveland area, but they came much later in his career, shortly before his death in 1959. His most widely known local patron was Louis Penfield, a high school art teacher with a modest income, who asked Wright to design a small but elegant “Usonian” house in a flood plain next to the Chagrin River in Willoughby, near the future path of Interstate 90. Wright created the term Usonian late in his career to denote a line of small, affordable houses he designed for middle-class clients, primarily across the Midwest. The contrast between Kaufmann—a wealthy merchant prince of Pittsburgh who sought Wright’s talents at the height of his career—and Penfield, a man of modest resources who caught up with Wright in his waning years, says a great deal about the skepticism with which business, political, and civic leaders in Cleveland viewed the latest ideas in art, architecture, and other areas of culture in the mid-20th century.

In 1937, Wright designed his most famous work, Fallingwater, for the Pittsburgh department store magnate, Edgar Kaufmann, as a retreat in the Pennsylvania mountains east of the city. Wright did receive commissions in the Cleveland area, but they came much later in his career, shortly before his death in 1959. His most widely known local patron was Louis Penfield, a high school art teacher with a modest income, who asked Wright to design a small but elegant “Usonian” house in a flood plain next to the Chagrin River in Willoughby, near the future path of Interstate 90. Wright created the term Usonian late in his career to denote a line of small, affordable houses he designed for middle-class clients, primarily across the Midwest. The contrast between Kaufmann—a wealthy merchant prince of Pittsburgh who sought Wright’s talents at the height of his career—and Penfield, a man of modest resources who caught up with Wright in his waning years, says a great deal about the skepticism with which business, political, and civic leaders in Cleveland viewed the latest ideas in art, architecture, and other areas of culture in the mid-20th century.

The city’s taste is instead embodied fully by the neoclassical civic buildings inspired by the 1903 Group Plan for downtown Cleveland, masterminded by Chicago architect Daniel H. Burnham. A brilliant planner and motivator of civic energy, Burnham launched the City Beautiful movement in American city planning with his plans for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The movement adapted Beaux Arts neoclassical architecture to American urban settings. The basic thrust was to sweep away the grime and slums of the Industrial Revolution and to impose the elegance and grandeur of Paris and Rome. Cleveland possesses a fine effort by Burnham—the May Company Building, along with the Society for Savings Building, designed by his partner, John Wellborn Root. But his greatest legacy is the 1903 Group Plan for downtown Cleveland, perhaps the largest intact example of City Beautiful planning in America, after the Mall in Washington, D.C., also influenced heavily by Burnham.

In Cleveland, the Group Plan called for a series of neoclassical civic buildings organized around a 12.5-acre central Mall, stretching from the Cleveland Public Library and the old federal post office and courthouse, north to an overlook between City Hall and the Cuyahoga County Courthouse. Burnham intended the three-block Mall to function as a vast promenade in the heart of downtown, with a large train station on the north end, overlooking Lake Erie. When the train station was built at Tower City Center, however, the Mall was deprived of its major activity generator. For decades, it has been a mixed legacy—a monumental space largely devoid of civic life. Plans for a new medical mart and convention center below Malls B and C, the northern sections of the space, offer the best chance in decades to complete Burnham’s vision and to inject fresh vitality into downtown’s largest public space.

If the Mall is an equivocal legacy, Burnham’s emphasis on neoclassical architecture—and essentially conservative taste—heavily influenced the city for decades. Neoclassicism, fundamentally a backward-looking style, was chosen for all major buildings in the city, from the Federal Reserve Building and Public Auditorium to the Cleveland Museum of Art, Severance Hall, and the Terminal Tower. Out-of-town firms designed some of the structures, but many were designed by some of the very fine local firms then operating in Cleveland, including Hubbell & Benes and Walker and Weeks. By the mid 1930s, however, when the Terminal Tower was finished, Burnham-style neoclassicism was utterly passé; New York had by then moved on to the far more progressive Art Deco styling of the Chrysler and Empire State buildings, Rockefeller Center, and the New York Daily News buildings.

Cutting-edge modernist architecture remained a minority taste throughout the 20th century in Cleveland, although it was embraced on occasion by a handful of private patrons. The Cleveland Artists Foundation, in an effort organized by local historian Nina Gibans, illuminated the history of a small group of modernist houses designed in Cleveland’s East Side suburbs in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s by local architects such as John Terrence Kelly, Don Hisaka, Robert A. Little, and Ernst Payer. The impression left by the show was that this handful of houses represented a high-water mark for design innovation during the period.

Tellingly, the Cleveland Chapter of the American Institute of Architects published a guide to Cleveland buildings in 1994, which avoided critical perspectives on local architecture. The one pointed exception is a comment in the introduction, by Theodore Sande, a Cleveland architect and preservationist, which stated that Cleveland architecture is “conservative or cautious” and that it tends to “reflect the end of a stylistic period, rather than the beginning.”

A TOLERANCE FOR MEDIOCRITY

The pattern continued after World War II, and in many ways, continues to this day. Architectural clients, including CEOs of the city’s largest banks, elevated the city’s skyline in the 1980s and ’90s with skyscrapers designed by some of the biggest names in contemporary architecture, including the national firms of HOK, SOM, Charles Luckman, Wallace Harrison, Hugh Stubbins, and Cesar Pelli. Local architects fumed at having been sidelined, even though most lacked the expertise to design skyscrapers. The local clients, however, weren’t able to coax the best work from the out-of-towners. Most of the postwar towers in downtown Cleveland are mediocre, grade B efforts by big, brand-name firms. Downtown gives permanent form to the impression that in architecture, Cleveland is a follower, not a leader. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, designed by I. M. Pei, is a prime example of the city’s conservatism. Designed relatively late in the architect’s career, it reprises themes he developed in earlier and better designs, such as the glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The conservatism of local architectural tastes is underscored by the city’s tepid response to the success of the most famous architect associated with the city, Philip Johnson. The son of a prominent Cleveland attorney, Johnson was briefly fascinated by fascism and Nazism in the 1930s, a phase he later bitterly regretted. With historian Henry Russell Hitchcock, Johnson curated a pivotal 1932 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which introduced European-style modern design to America. After World War II, he established himself as one of the most influential American architects of the second half of the 20th century. In 1948, he designed his famous Glass House residence for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut, now owned and operated as a house museum by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. His other credits include skyscrapers in New York, Denver, Houston, and Minneapolis, as well as the Fort Worth Water Garden and the Amon Carter Museum, also in Fort Worth.

As an architect, Johnson was a complete chameleon; he changed styles rapidly and capitalized on every new idea that emerged between the 1930s and the 1990s, often winning extensive media attention, which may have been the point. His outspoken style and flamboyant personal lifestyle—he was gay and came out of the closet proudly in the latter decades of his life—did not go over well in his hometown. He never got a major assignment in Cleveland until he was asked in the early 1980s to design a “post-modern” expansion of the Cleveland Play House complex at 85th Street and Euclid Avenue in an abstracted version of Byzantine architecture. Today, the Play House faces an uncertain future; the Cleveland Clinic purchased the complex in 2009 and, as of the fall of 2010, it had not yet announced whether it would demolish or keep Johnson’s building.

At times, Cleveland embraced innovation, but only at its most destructive. The 1961 Erieview Plan, masterminded by a young I. M. Pei, led to the wholesale demolition of 200 acres of downtown fabric, and paved the way for the sterile towers erected in the 1970s and ’80s. Along Superior Avenue and East Ninth Street, large towers are interspersed with parking garages, creating streetscapes of deadly and long-lasting dullness. During the same period, the city allowed building owners to demolish half of the buildings in the Warehouse District, to make way for surface parking lots that would serve the new City-County Justice Center.

CONSERVING THE PAST: THE RISE OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND THE GREEN MOVEMENT

In response, Cleveland’s cultural conservatism found an extremely positive outlet in the rise of a strong historic preservation movement. A modernist architect named Peter van Dijk, a native of Holland who grew up in Venezuela and suburban New York, played a key role in the movement. Van Dijk moved to Cleveland in the 1960s, after having spent a decade working for Eero Saarinen in Detroit on assignments including the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. Van Dijk overtly adapted Saarinen’s great steel parabolic arch in the design for his most important work, the Blossom Music Center, in 1968.

Frustrated thereafter by his inability to capture an assignment to design a major skyscraper downtown, van Dijk became a preservation architect, almost by accident. He played a key role in unifying the movie palaces of PlayhouseSquare with interconnected lobbies. His firm, capitalizing on the expertise in theater renovation it gained at PlayhouseSquare, subsequently renovated more than 150 historic theaters across the country—showing how a single assignment in Cleveland led to the strengthening of a hometown architecture firm. Today, Cleveland has a national reputation for high quality historic preservation, and for having saved much of its historic fabric. Ohio is a national leader in architecture and development firms taking advantage of federal historic tax credits to complete detailed, historically respectful renovations of important early 19th- and early 20th-century buildings. And within Ohio, Cleveland ranks first in tax credit work.

The industrialists who built Cleveland took little interest in the amenity value of the city’s waterfronts, which they used exclusively for commercial and industrial purposes. Consequently, residents and elected officials put up little opposition in the 1950s, when highway engineers walled off Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga Valley. Unlike Chicago, which pursued civic beauty with a passion in the creation of one of the world’s great waterfronts, Cleveland has tacitly expressed the attitude that beauty is enshrined inside the city’s art museums, not in the public realm.

At the outset of the 21st century, a broad social movement is underway to reclaim polluted industrial landscapes and turn them into parks and bikeways. Progress is slow, painfully so. But the landscape urbanism movement, also present in other cities around the country, is a highly positive trend and absolutely necessary if Cleveland is to survive in the future. If anything, it needs greater public and political support to speed up the creation of regional amenities that could do an enormous amount to change the city’s image and erase the memory of the 1969 fire on the Cuyahoga River.

RADICAL RESPONSE: THE RISE OF MOCA

No city is monolithic in its cultural tastes and that is certainly true of Cleveland. Throughout the 20th century, artists, collectors, and architects have championed new ideas, sometimes with truly amazing consequences. In 1968, progressive energies in the visual arts coalesced around a tiny institution called the New Gallery, later known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. It was founded by art impresarios Marjorie Talalay and Nina Sundell, daughter of the highly influential New York art dealer, Leo Castelli. When Talalay and Sundell opened their gallery in a former dry cleaning storefront on Euclid Avenue, the tiny space upstaged the Cleveland Museum of Art by hosting important exhibitions on the works of artists including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Christo. At a time when the Cleveland Museum of Art had few Jewish representatives on its board of trustees, MOCA, by then known as the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, provided an outlet for progressive and forward-looking tastes of many of the city’s Jewish art collectors and patrons. Chief among them were Peter and Toby Lewis. In one celebrated instance, a creative spark ignited at the center had global significance.

No city is monolithic in its cultural tastes and that is certainly true of Cleveland. Throughout the 20th century, artists, collectors, and architects have championed new ideas, sometimes with truly amazing consequences. In 1968, progressive energies in the visual arts coalesced around a tiny institution called the New Gallery, later known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. It was founded by art impresarios Marjorie Talalay and Nina Sundell, daughter of the highly influential New York art dealer, Leo Castelli. When Talalay and Sundell opened their gallery in a former dry cleaning storefront on Euclid Avenue, the tiny space upstaged the Cleveland Museum of Art by hosting important exhibitions on the works of artists including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Christo. At a time when the Cleveland Museum of Art had few Jewish representatives on its board of trustees, MOCA, by then known as the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, provided an outlet for progressive and forward-looking tastes of many of the city’s Jewish art collectors and patrons. Chief among them were Peter and Toby Lewis. In one celebrated instance, a creative spark ignited at the center had global significance.

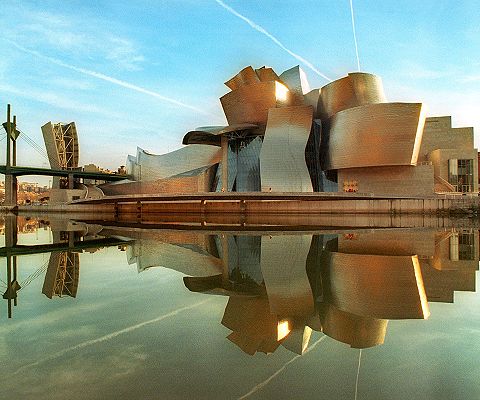

In the mid 1980s, the institution staged a lecture series on contemporary architecture, which brought the pioneering Los Angeles architect Frank Gehry to town. After the talk, Talalay introduced Gehry to Peter Lewis, by then a major MOCA supporter and art collector. Lewis challenged Gehry to design a house for him in Lyndhurst big enough to show off his collection—and to mark Lewis as a visionary patron of the arts. The project went through 15 major iterations, by which time the estimated cost of the house reached $80 million. Lewis, who no longer wanted to live in a big house, pulled the plug on the assignment. Lewis also asked Gehry to design a downtown skyscraper headquarters for Progressive next to Burnham’s Mall, overlooking Lake Erie. The project failed due to lack of political support from mayors George Voinovich and Michael White, and ambivalence on Lewis’s part.

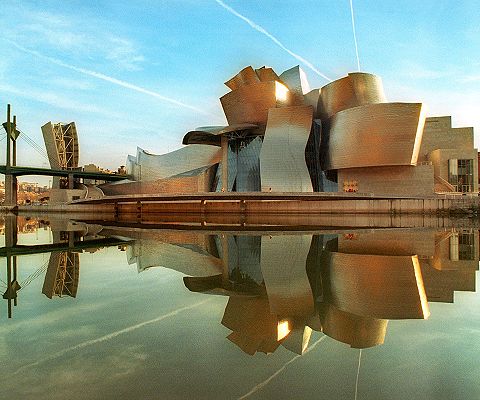

Lewis’s patronage, meanwhile, had an enormous impact on Gehry. It enabled him to master computer technology as an aid in designing and building highly sculptural forms never before attempted by the architect. The ultimate outcome of these years was Gehry’s design for the path-breaking Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997, which turned the city overnight into a global tourist attraction. Gehry has publicly acknowledged the importance of Lewis’s support, a point made visible in a documentary film Lewis commissioned to record his interactions with Gehry. Lewis subsequently paid for half of the construction cost of the Gehry-designed Peter B. Lewis Building at Case Western Reserve University, completed in 2002. Compromised by rapid turnover in the president’s office at CWRU and by uneven oversight, the project is not one of Gehry’s better buildings, which demonstrates how difficult it can be, even with a great architect, to achieve a great result.

Lewis’s patronage, meanwhile, had an enormous impact on Gehry. It enabled him to master computer technology as an aid in designing and building highly sculptural forms never before attempted by the architect. The ultimate outcome of these years was Gehry’s design for the path-breaking Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997, which turned the city overnight into a global tourist attraction. Gehry has publicly acknowledged the importance of Lewis’s support, a point made visible in a documentary film Lewis commissioned to record his interactions with Gehry. Lewis subsequently paid for half of the construction cost of the Gehry-designed Peter B. Lewis Building at Case Western Reserve University, completed in 2002. Compromised by rapid turnover in the president’s office at CWRU and by uneven oversight, the project is not one of Gehry’s better buildings, which demonstrates how difficult it can be, even with a great architect, to achieve a great result.

The connection between Cleveland and Bilbao is especially poignant because Bilbao is a global example of the ways in which a dying industrial city can help reverse its decline through calculated investments in cutting-edge art, architecture, and urban design. Gehry’s Guggenheim branch is the most famous international symbol of the new Bilbao. It is less widely known that the museum was part of a carefully thought out plan for Bilbao and environs, which called for a shining new subway system, designed by Lord Norman Foster of England, an airport designed by Spanish architect-engineer Santiago Calatrava, and a waterfront business district on the Nervion River, designed by American architect Cesar Pelli.

Bilbao offers one example of how a progressive cultural agenda can help turn a city around. For Cleveland, the key is not to imitate Bilbao, but to figure out how to address its own challenges in a uniquely local way, while spending money as wisely as possible. Today, the biggest public policy question facing the arts in Northeast Ohio is whether the cigarette tax supplying income for the county’s annual arts fund should be renewed when it expires in 2016. Closely related to this question is whether government and philanthropy working together can maintain the existing collection of cultural institutions in the city, or whether a smaller audience and philanthropic base will mean that some institutions will die.

Bilbao offers one example of how a progressive cultural agenda can help turn a city around. For Cleveland, the key is not to imitate Bilbao, but to figure out how to address its own challenges in a uniquely local way, while spending money as wisely as possible. Today, the biggest public policy question facing the arts in Northeast Ohio is whether the cigarette tax supplying income for the county’s annual arts fund should be renewed when it expires in 2016. Closely related to this question is whether government and philanthropy working together can maintain the existing collection of cultural institutions in the city, or whether a smaller audience and philanthropic base will mean that some institutions will die.

PICKING WINNERS AND LOSERS THROUGH CULTURAL PHILANTHROPY

In recent years, the city witnessed the demise of both the Cleveland San Jose Ballet and the Health Museum, both of which failed to raise enough endowment support to see them through lean times. The Health Museum’s collapse is noteworthy because it followed the museum’s construction of an architecturally ambitious building in the 1990s, which it could not afford to occupy once it was finished. The Cleveland Botanical Garden, which also expanded during the favorable economy of the 1990s, now faces a similar strain in the more difficult economic climate of the early 21st century. The Western Reserve Historical Society lavished millions of dollars on an expansion plan it ultimately abandoned, but not before having seriously damaged its finances.

No one knows exactly how much money exists for the arts and culture in Cleveland. But it’s fair to ask, for example, whether the ambitious expansion of the Cleveland Museum of Art will mean greater fiscal challenges for the Cleveland Orchestra, for example, or the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. It’s likely that arguments for and against funding of particular institutions will be grounded in quantitative measures, including numbers of school visits, attendance, and membership, along with economic impact studies of tourism, employment, and taxes. All those measures are important. However, when choosing which institutions or artists to support, it’s always important to remember that the core values of are based on the pursuit of quality, originality, and creativity, not easily measurable economic effects.

The mission statement of Cuyahoga Arts and Culture, the public agency charged with deciding how $15 million in county arts grants should be spent, makes it sound as if artistic quality is a primary objective. It states that the goal of the CAC is to “sustain the excellence of Cuyahoga County’s arts and cultural assets that enrich our lives and enhance our community’s appeal.” But the CAC language presumes that the institutions it supports have already achieved artistic excellence, which is essentially a boosterish, self-congratulatory notion. It also implies that preserving existing institutions and jobs should be a primary goal of arts funding. This is a fundamentally unexciting proposition. Can we expect more?

The Cleveland Museum of Art, which is in the midst of a transformation, may provide some of the answers. With its expansion and renovation only halfway complete, it’s unclear whether it will finally give modern and contemporary art the same level of attention it has paid to Ancient Greek, European medieval, or Asian art. Signs are the museum under new director David Franklin will finally address the shortcomings of its 20th-century collection, and hold major exhibitions on modern masters whose works have never been explored seriously in Cleveland.

As the museum considers its next moves, progressive cultural energy in Cleveland has focused on the Uptown development in University Circle. Uptown is an eight-acre, $150 million-plus real estate development that will combine rental housing, cultural institutions, retail, and restaurants on the triangle of land east of the intersection of Euclid Avenue, Ford Drive, and Mayfield Road. The project will be anchored on the west by a new, $26 million building for MOCA Cleveland, and on the east by an expanded campus for the Cleveland Institute of Art, centered on the Joseph McCullough Center for the Visual Arts.

In between, the real estate development company MRN, Ltd., will build approximately 150 apartments on both sides of Euclid Avenue, along with a Barnes & Noble bookstore, street-level cafes, bars, and restaurants. The new development will replace a dull, suburban-style strip shopping center built in the 1980s, surrounded by surface parking lots. Uptown, sponsored by Case Western Reserve University and University Circle, Inc., echoes dozens of campus-edge developments around the country, in which universities and medical centers have rebuilt the empty acres around the fringes of their campuses to create lively urban environments, aimed at attracting and retaining the best and brightest students, faculty, and workers.

The success of Uptown, with a healthy, expanded, and more popular MOCA, could do an enormous amount to shift the city’s cultural values and make it a more broad-minded place open to new ideas. Other progressive new ventures in the visual arts in Cleveland are also under way. The Cleveland Institute of Art, working with partners including Cleveland State University, wants to reignite interest in the Viktor Schreckengost legacy by making the city a major haven for industrial design. Someday, the Cleveland Institute of Art could also create a graduate school in the visual arts, which would entice mature artists to settle in the city. Kent State University could expand the footprint of its satellite Architecture and Urban Design Program in the city and enrich debate on how Cleveland shapes its future physically. Nonprofit organizations devoted to excellence in the design of parks and public spaces, such as ParkWorks and Cleveland Public Art, are thriving.

For civic leaders and philanthropists, the question is whether the flow of money to the arts should be determined by a true appreciation of artistic quality and innovation, not simply measurable economic impact. In a city with a shrinking population and diminishing resources, demands for arts funding may rise, even as the supply of available cash becomes scarce. Foundations, donors, and government will have to make tough decisions about where to invest. Quality is never a bad investment, but innovation is equally important. As a city whose history of cultural conservatism has paralleled its long economic decline, Cleveland needs to consider how it can preserve and celebrate the best of the past, while also becoming a place where new and original thinking is not only encouraged, but demanded. Cleveland needs to become a place that generates new ideas, not just one that imports artistic concepts or popularizes existing ideas in order to realize quick financial gain. Cleveland needs more people like Charles Burchfield, Viktor Schreckengost, and Peter Lewis—not another Archibald Willard.

SOURCES

Adams, Henry. Viktor Schreckengost and 20th Century Design. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, distributed by Washington University Press, 2000.

Gaede, Robert, and Richard van Petten. Guide to Cleveland Architecture. 2nd ed. Cleveland: Cleveland Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, 1997.

Johannesen, Eric. A Cleveland Legacy: The Architecture of Walker and Weeks. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1999.

———. Cleveland Architecture, 1876–1976. Rev. ed. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1981.

Litt, Steven. “Cleveland’s Long-time Love Affair with Culture.” The Plain Dealer, Special Section: The Life of a City/Cleveland Celebrates its Bicentennial, December 31, 1995.

———. “The Forgotten Valley” (series of 5 articles). The Plain Dealer, November 19–25, 2000.

Miller, Carol Poh, and Robert Wheeler. Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796–1996. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

The New American City Faces Its Regional Future: A Cleveland Perspective. Edited by David C. Sweet, Kathryn Wertheim Hexter, and David Beach. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1999.

Transformations in Cleveland Art: 1796–1946. Edited by William Robinson and David Steinberg. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1996.

Witchey, Holly Rarick, and John Vacha. Fine Arts in Cleveland: An Illustrated History. Vol 3, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of

The trustee thought so little of the bronze, which depicts a pair of lesbians embracing, that he used it as a doorstop. Such negative attitudes, made manifest subtly through art acquisitions and exhibitions that focused primarily on pre-modern art, communicated a powerful disdain for the 20th century and had a dampening effect on contemporary art in Cleveland. To counteract this tendency and provide encouragement to local artists, the museum started an annual series of juried exhibitions on Cleveland art in 1919, called the May Show, which stimulated the competitive spirits of local artists and inspired local collectors to acquire works selected for display. As popular as it was, however, the May Show failed to place local art in a broader national or international context and in that sense contributed to a prevailing sense of cultural isolation. The museum underscored the message by rarely exhibiting works it purchased from the May Show among other works in the collection. It wasn’t until the opening of the museum’s new East Wing in the summer of 2009 that it created special galleries dedicated to the art of Northeast Ohio.

The trustee thought so little of the bronze, which depicts a pair of lesbians embracing, that he used it as a doorstop. Such negative attitudes, made manifest subtly through art acquisitions and exhibitions that focused primarily on pre-modern art, communicated a powerful disdain for the 20th century and had a dampening effect on contemporary art in Cleveland. To counteract this tendency and provide encouragement to local artists, the museum started an annual series of juried exhibitions on Cleveland art in 1919, called the May Show, which stimulated the competitive spirits of local artists and inspired local collectors to acquire works selected for display. As popular as it was, however, the May Show failed to place local art in a broader national or international context and in that sense contributed to a prevailing sense of cultural isolation. The museum underscored the message by rarely exhibiting works it purchased from the May Show among other works in the collection. It wasn’t until the opening of the museum’s new East Wing in the summer of 2009 that it created special galleries dedicated to the art of Northeast Ohio. of these “Cleveland School” artists is fascinating, in that it illuminates the history of Cleveland and evokes an extraordinary sense of place. A 1908 painting of a fire tug on the Cuyahoga River, painted by Biehle, exhibited in the 1996 exhibition on Cleveland art, conveys a sense of the smoke-shrouded Flats during the city’s industrial heyday in broad strokes of sooty browns and beiges. Gaertner’s 1926 Pie Wagon, purchased by the museum, shows steel workers gathered outside a soot-shrouded factory on a patch of blinding snow, eating snacks sold by vendors.

of these “Cleveland School” artists is fascinating, in that it illuminates the history of Cleveland and evokes an extraordinary sense of place. A 1908 painting of a fire tug on the Cuyahoga River, painted by Biehle, exhibited in the 1996 exhibition on Cleveland art, conveys a sense of the smoke-shrouded Flats during the city’s industrial heyday in broad strokes of sooty browns and beiges. Gaertner’s 1926 Pie Wagon, purchased by the museum, shows steel workers gathered outside a soot-shrouded factory on a patch of blinding snow, eating snacks sold by vendors.

In 1937, Wright designed his most famous work,

In 1937, Wright designed his most famous work,

No city is monolithic in its cultural tastes and that is certainly true of Cleveland. Throughout the 20th century, artists, collectors, and architects have championed new ideas, sometimes with truly amazing consequences. In 1968, progressive energies in the visual arts coalesced around a tiny institution called the New Gallery, later known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. It was founded by art impresarios Marjorie Talalay and Nina Sundell, daughter of the highly influential New York art dealer, Leo Castelli. When Talalay and Sundell opened their gallery in a former dry cleaning storefront on Euclid Avenue, the tiny space upstaged the Cleveland Museum of Art by hosting important exhibitions on the works of artists including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Christo. At a time when the Cleveland Museum of Art had few Jewish representatives on its board of trustees, MOCA, by then known as the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, provided an outlet for progressive and forward-looking tastes of many of the city’s Jewish art collectors and patrons. Chief among them were Peter and Toby Lewis. In one celebrated instance, a creative spark ignited at the center had global significance.

No city is monolithic in its cultural tastes and that is certainly true of Cleveland. Throughout the 20th century, artists, collectors, and architects have championed new ideas, sometimes with truly amazing consequences. In 1968, progressive energies in the visual arts coalesced around a tiny institution called the New Gallery, later known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. It was founded by art impresarios Marjorie Talalay and Nina Sundell, daughter of the highly influential New York art dealer, Leo Castelli. When Talalay and Sundell opened their gallery in a former dry cleaning storefront on Euclid Avenue, the tiny space upstaged the Cleveland Museum of Art by hosting important exhibitions on the works of artists including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Christo. At a time when the Cleveland Museum of Art had few Jewish representatives on its board of trustees, MOCA, by then known as the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, provided an outlet for progressive and forward-looking tastes of many of the city’s Jewish art collectors and patrons. Chief among them were Peter and Toby Lewis. In one celebrated instance, a creative spark ignited at the center had global significance. Lewis’s patronage, meanwhile, had an enormous impact on Gehry. It enabled him to master computer technology as an aid in designing and building highly sculptural forms never before attempted by the architect. The ultimate outcome of these years was Gehry’s design for the path-breaking Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997, which turned the city overnight into a global tourist attraction. Gehry has publicly acknowledged the importance of Lewis’s support, a point made visible in a documentary film Lewis commissioned to record his interactions with Gehry. Lewis subsequently paid for half of the construction cost of the Gehry-designed Peter B. Lewis Building at Case Western Reserve University, completed in 2002. Compromised by rapid turnover in the president’s office at CWRU and by uneven oversight, the project is not one of Gehry’s better buildings, which demonstrates how difficult it can be, even with a great architect, to achieve a great result.

Lewis’s patronage, meanwhile, had an enormous impact on Gehry. It enabled him to master computer technology as an aid in designing and building highly sculptural forms never before attempted by the architect. The ultimate outcome of these years was Gehry’s design for the path-breaking Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, completed in 1997, which turned the city overnight into a global tourist attraction. Gehry has publicly acknowledged the importance of Lewis’s support, a point made visible in a documentary film Lewis commissioned to record his interactions with Gehry. Lewis subsequently paid for half of the construction cost of the Gehry-designed Peter B. Lewis Building at Case Western Reserve University, completed in 2002. Compromised by rapid turnover in the president’s office at CWRU and by uneven oversight, the project is not one of Gehry’s better buildings, which demonstrates how difficult it can be, even with a great architect, to achieve a great result. Bilbao offers one example of how a progressive cultural agenda can help turn a city around. For Cleveland, the key is not to imitate Bilbao, but to figure out how to address its own challenges in a uniquely local way, while spending money as wisely as possible. Today, the biggest public policy question facing the arts in Northeast Ohio is whether the cigarette tax supplying income for the county’s annual arts fund should be renewed when it expires in 2016. Closely related to this question is whether government and philanthropy working together can maintain the existing collection of cultural institutions in the city, or whether a smaller audience and philanthropic base will mean that some institutions will die.

Bilbao offers one example of how a progressive cultural agenda can help turn a city around. For Cleveland, the key is not to imitate Bilbao, but to figure out how to address its own challenges in a uniquely local way, while spending money as wisely as possible. Today, the biggest public policy question facing the arts in Northeast Ohio is whether the cigarette tax supplying income for the county’s annual arts fund should be renewed when it expires in 2016. Closely related to this question is whether government and philanthropy working together can maintain the existing collection of cultural institutions in the city, or whether a smaller audience and philanthropic base will mean that some institutions will die.