The 1948 baseball photo with a radical message of acceptance

By Frederic J. Frommer

Washington Post, October 9, 2023

Like Jackie Robinson before him, Larry Doby — the first Black player in baseball’s American League — endured racist taunts from fans and opposing players, discrimination in hotels and restaurants and even hostility from his teammates. For Doby, a World Series embrace with a White teammate was an antidote to that torrent of abuse.

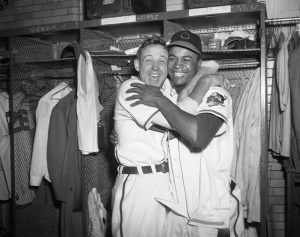

Doby, who made his major league debut in July 1947, less than three months after Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier, had a breakout season the next year, leading the Cleveland Indians to the AL pennant. In Game 4 of the 1948 World Series — 75 years ago Monday — his 425-foot solo homer to right-center proved to be the difference in a 2-1 victory over the Boston Braves and their ace, 24-game winner Johnny Sain. After the game, Doby threw his arm around winning pitcher Steve Gromek in the clubhouse, and the men embraced, cheek-to-cheek, exuberant smiles etched on their faces.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer took a photo of that moment, which the Associated Press transmitted to newspapers across the country — the 1940s version of an image going viral. Many Americans saw it as a symbol of progress at a time when Black players were barely tolerated, while others recoiled from it.

“That was a feeling from within, the human side of two people, one Black and one White,” Doby said years later, according to the New York Times. “That made up for everything I went through. I would always relate back to that whenever I was insulted or rejected from hotels. I’d always think about that picture. It would take away all the negatives.”

The embrace “was special because it was the first time anyone showed feeling toward me as far as I’m concerned. I mean, toward an African American,” Doby told the Chicago Tribune in 1995. “Until then they had been distant, cool, and [Gromek] got criticized for what he did back home. … I think it was the first picture taken of that type, the first picture of a black American and a white American embracing each other going out all over the country.”

Gromek’s complete-game win in front of more than 80,000 at Cleveland Stadium that afternoon gave the Indians a 3-1 series lead. They would go on to win the series in six games — the franchise’s most recent World Series title. Doby’s homer was the first by a Black player in the World Series, and he led all Cleveland regulars that series with a .318 batting average.

“That was probably the most special moment in his career,” Doby’s son, Larry Doby Jr., told the Athletic in 2020. “It was just two guys who were expressing an unbridled joy over accomplishing a common goal. I think that picture really encapsulates what that journey and the hardships meant to him.”

Gromek, who died in 2002, told the Plain Dealer that “it seemed in the picture like I was kissing him. I was being interviewed in front of my locker, and somebody asked Larry to come over. He put his arm around me and squeezed me so hard I thought he was going to break my ribs. We were both so happy.”

But not everyone was happy. That winter, Gromek came home to a cold reception in Hamtramck, Mich., and angry letters flooded his mailbox. He once recalled walking into a neighborhood bar that offseason.

“I saw a guy I had known for more than 10 years, a guy I had played ball with,” he said, according to the Society for American Baseball Research. “I said hello, and he ignored me.” The bartender told Gromek what was eating the man — “Oh, Christ, it’s that picture you took with Larry Doby.”

“So then the guy told me, ‘Jesus, you could have just shook his hand,’ ” Gromek continued. “But then this other friend of mine says, ‘If I was in Steve’s shoes and Doby did what he did, I would have kissed him.’ ”

“Some of his friends really reacted negatively,” son Greg Gromek told the Guardian in 2016. “They said things that were sort of shocking to him. What bothered him was that these were his friends. He kept thinking, ‘What kind of friend are you to say these things?’ He even got death threats. That’s what was really shocking.”

On the other hand, some Black Americans found the photo inspiring.

“That picture of Gromek and Doby has unmistakable flesh and blood cheeks pressed close together, brawny arms tightly clasped, equally wide grins,” Marjorie McKenzie wrote in the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, as recounted by the Times. “The chief message of the Doby-Gromek picture is acceptance.”

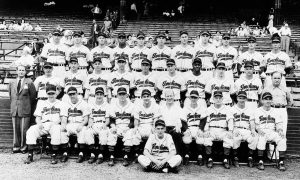

The Indians signed Doby in July 1947. Unlike Robinson, Doby came straight from the Negro Leagues, without any preparation in the minor league system. He got a cold shoulder when Cleveland’s player-manager, Lou Boudreau, introduced him to his new teammates, as he told the (Newark) Star-Ledger’s Jerry Izenberg.

“I walked down that line and stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return,” recalled Doby, who died in 2003. “Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.’

“Now, I couldn’t believe how this was. I put on my uniform, and I went out on the field to warm up, but nobody wanted to warm up with me. I had never been so alone in my life. I stood there alone in front of the dugout for five minutes. Then Joe Gordon, the second baseman who would become my friend, came up to me and asked, ‘Hey, rookie, you gonna just stand there, or do you want to throw a little?’ I will never forget that man.”

Less than a month into his big league career, the Indians came to Washington to play the Senators (also known as the Nationals), and some local fans used the occasion to pressure their home team to integrate. “Cleveland has a colored ball player — why not Washington?” one placard read. “Brooklyn signed a Negro player — why don’t the Nats?”

Doby saw the signs when he got out of a cab and told Gordon, his closest friend on the team, “Jeez, Joe, I don’t want to be a symbol — I just want to be a big league player,” according to Washington Post sports columnist Shirley Povich. The Senators averaged more than 16,000 in attendance for the three-game series — compared with their average crowd of just over 11,000. But the local pressure campaign didn’t work — Washington would be one of the last teams to sign a Black player, in 1954. (Before Doby joined the Indians, the Senators passed up an opportunity to sign him.)

Doby hit just .156 in 32 at-bats his first season, mostly as a pinch hitter, and there was some doubt as to whether he would return in 1948. The Indians brought in Tris Speaker, the Hall of Fame outfielder and former Cleveland manager, to tutor Doby as he transitioned from second base to center field. On the surface, this move seemed sure to add more stress on the lonely young player. Speaker, who was from Hubbard, Tex., had allegedly once been a member of the Ku Klux Klan and referred to the Civil War as “The War of Northern Aggression.”

Yet the two got along well.

“In another year or two he could be the best player in this league,” Speaker told Povich early in Doby’s career. “I’ve never seen a young ballplayer with such a high potential. I get a personal pleasure out of working with a kid who can do so many things so well. I used to dream of that kind of rookie when I was managing the Indians.”

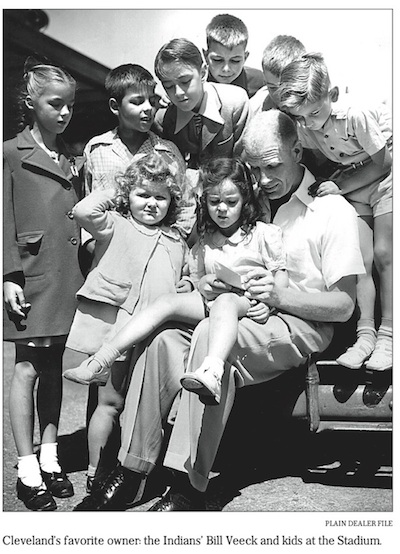

Doby hit his stride in 1948, batting .301 with a team-high nine triples to help the Indians dethrone the New York Yankees for the AL pennant — Cleveland’s first since 1920, when Speaker was player-manager. In July 1948, Doby finally had a Black teammate when Indians owner Bill Veeck signed legendary pitcher Satchel Paige.

While baseball was slowly shedding its Jim Crow past, Southern politicians were working to preserve Jim Crow policies in their states. The same month that Paige joined Cleveland, Southern segregationist Democrats bolted from the party at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, furious at the party’s bold civil rights platform, and put forth Strom Thurmond as their “Dixiecrat” nominee. Earlier that year, President Harry S. Truman had hastened the party’s rupture byproposing a set of far-reaching civil rights measures.

On July 15, the day after the dramatic party breakup, Doby and the Indians came to Philadelphia’s Shibe Park for a key matchup, clinging to a half-game lead over the second-place Philadelphia Athletics. The Indians swept the doubleheader, with Doby going 3 for 10 with a double and a home run. Gromek pitched a four-hitter in the opener, and Paige won his first major league game in the nightcap.

Paige would be a solid contributor that season, going 6-1 with a 2.48 ERA. But it was Doby who helped carry the team to the pennant. As Boudreau said in the stretch drive of September: “Without Doby, we would not be fighting for the pennant. We probably would have been in fourth place.”

Cleveland finished in a tie for first place with the Boston Red Sox (there were no divisions back then), so they met for a winner-take-all game at Fenway Park on Oct. 4 to decide the pennant. A Red Sox victory would have led to an all-Boston World Series. But the Indians thrashed those Beantown dreams with an 8-3 victory. Doby hit a pair of doubles. For the second straight year, an integrated team went to the World Series, following the Brooklyn Dodgers’ National League pennant in 1947.

After his 1948 World Series heroics, Doby, a future Hall of Famer, would play another 11 seasons. A seven-time MLB all-star, his best year was probably 1950, when he hit .326 with 25 homers and 102 RBI while leading the AL with a .442 on-base percentage and slugging .545. When the Indians won another pennant in 1954, Doby led the AL in home runs and RBI and finished second in the MVP vote to Yankees catcher Yogi Berra.

In 1978, Veeck, then the owner of the Chicago White Sox, named Doby his manager — making him, coincidentally, also the majors’ second Black manager, following Frank Robinson. At the time, Doby reflected on the 30-year-old photo, but this time he put himself in Gromek’s shoes.

“I don’t know what he thought later that night when he went home,” Doby told the Chicago Tribune, “but when you win, color sort of disappears because the joy in you comes out. At that particular moment, I don’t think you have any prejudice even if it’s in you. The joy just takes over.”