Courtesy of the Jewish Virtual Library and the Encyclopaedia Judaica

The link is here

CLEVELAND, city situated in Northeast Ohio on Lake Erie. Its metropolitan area has the largest Jewish population in the state (81,500 in 1996). Jewish settlement began in the 1830s, when Daniel Maduro Peixotto (1800–43) joined the faculty of Willoughby Medical College in 1836 and Simson Thorman (1812–1881), a trader in hides, came from Unsleben, Bavaria, settling permanently in Cleveland in 1837. The opening of the Ohio and Erie canals and the development of stage routes provided countless economic opportunities for new immigrants, and Thorman must have written to his family in Unsleben; in 1839 a group of 19 departed on the sailing shipHoward and 15 made the trip to Cleveland, arriving in July of that year, joining two other men who had emigrated from Unsleben.

Community Life to 1865

The Unsleben group arrived in America prepared to continue Jewish observance. They carried with them an ethical testament, known as the Alsbacher Ethical Testament, written by their teacher in Unsleben, who implored them not to forsake their heritage. Simson Hopferman (later Hoffman) served as a ḥazzan and shoḥet.They had a Sefer Torah, and with enough men to form a minyan, established the Israelitic Society in 1839. In 1840 the group purchased land on Willett Street for a cemetery, and more Jewish settlers arrived. There were two married and five single women with the Howard group, and marriages and births quickly followed.

In 1841 internal divisions led to the formation of a second congregation, Anshe Chesed (today known as Anshe Chesed Fairmount Temple). The two groups reunited temporarily, but split again in 1850, when a group of some 20 dissidents left to establish Tifereth Israel (today known as The Temple – Tifereth Israel). Rabbi Isadore Kalisch (1816–1886), later coauthor with Isaac Mayer *Wise of the first American Reform prayer book, Minhag America, led the new congregation. Both congregations moved towards reform before the Civil War.

In addition to the congregations, there were six communal organizations that were established before the end of the Civil War, including a local chapter of B’nai B’rith (1853), the Hebrew Benevolent Society (1855), the Young Men’s Literary Society (1860), the Jewish Ladies Benevolent Society (1860), the Zion Singing Society (1861), and the Hungarian Aid Society (1863). These reflected the growth of the Jewish community to approximately 1,000 individuals, 78% from German states (primarily Bavaria), and 19% from the Austrian Empire (primarily Bohemia). Benjamin Franklin Peixotto (1834–1890) was a founder of some of these organizations; while living in Cleveland, he owned a clothing factory and wrote for the local newspaper, The Plain Dealer, before leaving the area.

Most of Cleveland’s Jews through the Civil War were laborers, peddlers, or small merchants, but even then they were gravitating toward the garment industry, which was to become the nation’s second largest concentration of such businesses. Several Jewish firms made uniforms for Civil War soldiers, including Sigmund Mann and Davis and Peixotto & Co. Some 38 men from Cleveland served in the Civil War, including Joseph A. Joel, later known for his comic description of a wartime Passoverseder published in the Jewish Messenger in 1862.

From 1865 to the 1890s

The Cleveland Jewish population grew from approximately 1,000 at the close of the Civil War to 3,500 in 1880. During this period the pioneering families and newer settlers established congregations and cultural institutions, built businesses, and were active in public affairs and politics. B’nai Jeshurun and Anshe Emeth (both still in existence in 2004 with the latter known today as Park Synagogue) were founded, respectively, by Hungarian and Polish immigrants in 1866 and 1869, while the earlier congregations, Anshe Chesed and Tifereth Israel, continued to grow. The Jewish Orphan Asylum (today known as Bellefaire) was established by B’nai B’rith in 1868 to care for the region’s Civil War orphans. The Hebrew Immigration Aid Society (1875) and Montefiore Home to serve the aged (1881) were formed to complete services to a growing community. The Jewish elite enjoyed the Excelsior Club (1872). The Anglo-Jewish press began with the Hebrew Observer in 1889; four years later the Jewish Review appeared, and the two merged as The Jewish Review and Observer in 1899. The Jewish Independent was founded in 1906.

Members of the community were successful in business and public affairs. Kaufman Hays (1835–1916) began as a peddler, and in 1894 took over the Cleveland Worsted Mills. Other major clothing manufacturers were Joseph and Feiss, Richman Brothers, Printz-Biederman, and Kaynee. The major department stores, Halles, The May Company, and Sterling Lindner, were owned or managed by Jews.

Jewish participation in general community life took many directions. By 1892 a number of Jewish merchants were members of the Cleveland Board of Trade, whose president that year was Frederick Mulhauser, a mill owner. Rabbi Moses J. Gries (1868–1918) was a trustee member of the Society of Organized Charities, founded in 1881. Baruch Mahler and Peter Zucker were presidents of the Board of Education (1884–85 and 1887–88), and Kaufman Hays was vice president of the City Council in 1888. Louis Black, of Hungarian origin, served as United States consul in Budapest under presidents Cleveland and Harrison. Joseph C. Bloch became the first Jewish judge in Cleveland.

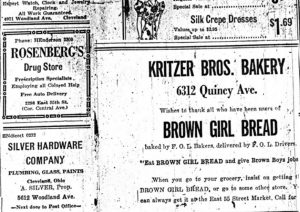

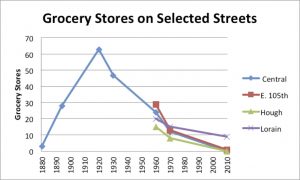

The 1890s through World War I: The Impact of East European Immigration

The Jewish population of Cleveland increased greatly from the 1880s on, as East Europeans fled pogroms and economic hardships. In 1890 the Jewish population was over 5,000 and by 1900 it was 20,000; at the end of the immigration period the estimated Jewish population of Cleveland was between 90,000 and 100,000. Clustered in the Woodland Avenue/55th Street neighborhood, the East Europeans worked as peddlers, in small businesses, and as employees in the clothing industry dominated by the established firms of the preceding immigrant generation. The new settlers were more attached to Orthodox traditions, and decidedly poorer, putting a strain on the existing social institutions. The Cleveland Section of the National Council of Jewish Women (founded in 1894) created an ambitious social settlement house through the Council Educational Alliance in 1899. To prevent duplication of efforts in activities and fundraising, in 1903 the established leadership created the Federation of Jewish Charities. In spite of these efforts, there were tensions between the newcomers and the earlier settlers. The East Europeans created their own institutions, including the Yiddishe Velt, a newspaper established by Samuel Rocker in 1911, a Jewish Relief Society (1895), an Orthodox Home for the Aged (1906, today known as Menorah Park Center for Senior Living), and the Orthodox Orphan Home. An attempt to create an Orthodox hospital failed when the existing Mt. Sinai Hospital (founded in 1903) agreed to provide kosher food. Numerous landsmanshaften also helped new immigrants adjust to Cleveland life, and at least 25 small Orthodox congregations could be found in the neighborhood, often associated with their members’ place of origin in Europe. Yiddish theater flourished in the community; one of the theater owners, Harry “Czar” Bernstein (1856–1920), was also a colorful Republican ward boss.

Many of the East European immigrants brought with them a trade-union outlook. The years before World War I were the high point of Jewish labor activity, particularly in the garment industries, where a series of strikes, not all successful, took place. A notable example of Jewish trade unionism was the Jewish Carpenters’ Union Local No. 1750, chartered in 1903. In 1910 William Goldberg began his lifelong leadership of the union and became a prominent figure in Ohio labor circles. Years later the garment workers’ union and the carpenters’ local lost their Jewish character as Jewish occupations shifted to the professions, service industries, and business enterprises. Unique expressions of Jewish economic activity were the Cleveland Jewish Peddlers’ Association, formed in 1896, and the Hebrew Working Men’s Sick Benefit Association.

Jewish Life through World War II

With the East European influx into Cleveland also came enthusiasm for Zionism. While Reform rabbis Moses Gries and Louis Wolsey opposed the movement, Zionist groups of all political persuasions proliferated, especially after two new rabbis were installed at the Reform congregations, Abba Hillel *Silver (1893–1963) andBarnett R. *Brickner (1892–1958). Many national conferences were held in Cleveland, notably the 1921 meeting that led to a schism between the factions headed byLouis *Brandeis and Chaim *Weizmann. *Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization, was established in Cleveland in 1913, and a Cleveland nurse, Rachel (Rae) Landy (1884–1952), along with New Yorker Rose Kaplan began visiting nurse services in Palestine that year. Zionism also affected Jewish education. Abraham H. *Friedland (1892–1939), brought from New York to direct the Talmud Torah supplementary school system, infused Hebrew language and Zionist philosophy into its educational curriculum. He also headed the Bureau of Jewish Education (founded in 1924) until his death in 1939.

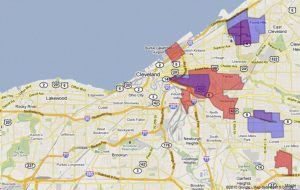

After World War I, the Jewish community migrated east of the Woodland neighborhood: Glenville, a city neighborhood northeast, became a center of middle-class life with Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform congregations, and boasted a much admired public school system which had illustrious graduates such as U.S. Senator Howard Metzenbaum (b. 1917) (D-Ohio) and Joe *Shuster (1914–92) and Jerome *Siegel (1914–1996), creators of the comic hero Superman. Mt. Pleasant-Kinsman, to the southeast, larger geographically but less densely Jewish, had only an Orthodox synagogue and was noted for its working-class and Yiddish-language atmosphere, with trade union headquarters and organizations such as the Workmen’s Circle. The more affluent began settling in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, and in 1926 B’nai Jeshurun, which had joined the Conservative movement, built an impressive structure in Cleveland Heights, where it was known for the next 55 years as Temple on the Heights.

The events of the 1930s – economic depression and increased local and international antisemitism – moved the Jewish community in various ways. First, the Federation of Jewish Charities underwent an effective reorganization, creating a Welfare Fund to coordinate fundraising and a Community Council to mediate local disputes and represent the Jewish community to the general public. Second, the nonsectarian League for Human Rights, led behind the scenes by Abba Hillel Silver, strongly reacted to events in Europe by boycotting German-made products, monitoring the German-American Bund and other such organizations’ local activities, and providing an organized response to German student exchange in Cleveland. Several Jewish Clevelanders, including David Miller (1908–1977) and Morris Stamm (1904–2000), served in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War.

By the eve of World War II, Cleveland Jewry had fewer internal disagreements as the more recent immigrants had acculturated and the leadership of major organizations was no longer exclusively in the hands of the earlier families’ descendants. Although there was never a Jewish mayor of Cleveland, Jews were active in local politics and in the judiciary. Alfred A. *Benesch (1879–1973) served for 37 years on the Cleveland Board of Education, Maurice Maschke (1868–1936) was a Republican leader between 1900 and 1940, and judges Samuel H. *Silbert (1883–1976) and Mary Belle Grossman (1879–1977) had long periods of service on the bench.

World War II and the Establishment of the State of Israel

Of the 8,500 Cleveland men and women who served in the armed forces during World War II, over 200 lost their lives. In 1943 Rabbi Barnett Brickner was selected by the National Jewish Welfare Board to serve as executive chairman of the Committee on Army and Navy Religious Activities and traveled throughout the war theaters. The Telshe Yeshiva was relocated in Cleveland, its rabbis escaping Europe prior to its destruction. Several thousand Holocaust survivors settled in the metropolitan area after the war was over.

In 1945 David *Ben-Gurion met with 17 Americans at the Sonneborn Institute to discuss strategies in anticipation of establishing the State of Israel. Among them was former Cleveland law director Ezra Z. *Shapiro (1903–1971), who would later immigrate to Israel to head *Keren Hayesod. Continuing his activist role in rallying the community to the Zionist cause, Abba Hillel Silver dramatically addressed the United Nations in 1947 calling for a Jewish state. Over the years, after the establishment of the state, the Israeli landscape would become dotted with schools, synagogues, community centers, parks, and businesses bearing the names of Cleveland-area philanthropists and Zionists, including Max Apple, the Mandel, Ratner, and Stone families, and the Cleveland sections of ZOA, Hadassah, Na’amat USA, Amit Women, and the Histadrut.

Post–World War II through the 1970s

The trickle of families into the Eastern suburbs accelerated after World War II, and the bulk of the population relocated to Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, South Euclid, University Heights, and Beachwood despite some restrictive covenants that were overturned. Institutions quickly followed, leading to the merger of no fewer than 15 smaller Orthodox congregations into Taylor Road Synagogue, Warrensville Center Synagogue, Green Road Synagogue, and Heights Jewish Center. The massive Cleveland Jewish Center, originally Anshe Emeth, relocated from Glenville into an architecturally notable building in Cleveland Heights designed by Eric Mendelsohn, and became known as Park Synagogue. This congregation had joined the Conservative movement earlier in the century after a fierce legal battle. The Reform movement experienced growth in the suburbs as well. Two new congregations, Emanu El and Suburban Temple, were founded. Arthur J. *Lelyveld (1913–1996) led Anshe Chesed Fairmount Temple from 1958 to 1986. Active in the civil rights movement, Lelyveld was severely beaten in Mississippi in 1964, and also officiated at the funeral of slain civil rights worker Andrew Goodman. At the Temple-Tifereth Israel, Daniel Jeremy Silver (1928–1989) became senior rabbi upon the death of his father, Abba Hillel Silver; he oversaw that congregation’s building of a satellite structure in the suburbs, published several scholarly works, and was instrumental in establishing the National Foundation for Jewish Culture.

Although a 1962 book called Cleveland “a city without Jews,” this was not strictly accurate, as Beth Israel-The West Temple served the Jews living on Cleveland’s West Side. This small congregation made several important contributions to Cleveland’s Jewish history. Scientists were important in its founding, among them Abe Silverstein (1920–2002), who worked at the nearby NASA Lewis Research Station and contributed to the Mercury and Apollo programs of the U.S. space effort. One of the congregation’s students, Sally *Priesand, went on to become the nation’s first female rabbi, and in 1963 three of its members founded the Cleveland Council on Soviet Antisemitism, the first known advocacy group in the Soviet Jewry movement which would eventually lead to some 6,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union settling in Northeast Ohio.

This was an extremely productive time for the Jewish Community Federation, which in 1951 merged its two divisions, the Jewish Welfare Federation and the Jewish Community Council. Under the leadership of Sidney Z. Vincent (1912–1982) and Henry L. Zucker (1910–1998), the Federation was the first in the nation to directly fund day school education (to the Orthodox Hebrew Academy), pioneered leadership training courses, and developed a comprehensive approach to building endowment funds. Cleveland was subsequently known as the most successful city in the United States in per capita fundraising as well as a training ground for future federation directors. In later years, Boston, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Seattle, and New York, among others, would be headed by individuals who started their careers in Cleveland.

The workforce moved from the labor unions into the professions, service industries, light manufacturing, and banking. Fewer spoke Yiddish, and the longtime Yiddish newspaper ceased publication in 1952. In 1964 the two English-language newspapers became the Cleveland Jewish News, which continues as an independent publication.

1975 to 2006

In the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st, the Cleveland Jewish community has been concerned with geography and identity. The numbers appear to have remained constant; although a 1987 population survey showed a decline to 65,000, the 1996 survey estimated the population to be 81,500, casting some doubts on the previous survey’s methodology. The inner ring eastern suburbs house nearly half of this population, yet movement to more affluent areas farther east continues, including institutions. A concerted effort by the Jewish Community Federation to slow population movement from Cleveland Heights has succeeded to some extent in keeping several centers of Jewish life viable. In Cleveland Heights, the Taylor Road area is home to kosher stores, the Jewish Education Center of Cleveland (a reconfigured Bureau of Jewish Education, founded earlier in the century), several Orthodox synagogues, including a Taylor Road Synagogue with a much smaller membership, and two large Orthodox day schools. Hebrew Academy, Cleveland’s first day school, continues to thrive in its Taylor Road location, while the ultra-Orthodox-built Mosdos Ohr Hatorah’s girl’s division is close by. Park Synagogue (Conservative) has its main sanctuary several blocks away, and a new egalitarian traditional congregation purchased Sinai Synagogue, whose members now meet farther east in University Heights. Chevrei Tikva, a congregation reaching out to gays and lesbians (founded in 1983), also meets in Cleveland Heights. In University Heights, Fuchs Mizrachi School (founded in 1983) has grown rapidly to over 300 students, from preschool through high school in a Zionist, Orthodox setting.

Another center of Orthodox life flourishes in the Green Road area, the border between Beachwood and University Heights. Green Road Synagogue moved here in 1972, later joined by Chabad of Beachwood and Young Israel in reconverted houses. In the late 1990s, Chabad, Young Israel, and the Hebrew Academy proposed building plans for an Orthodox campus in this location, which were accepted, rejected, and then accepted with modifications during a period of contentious discussions noted nationally as an example of dissension within the Jewish community. The Jewish Federation created a task force, B’Yachad/Together, to try to heal some of these rifts. The Beatrice Stone Yavne School for Girls has since been built, as has the new Young Israel building, with Chabad under construction at this writing. The Green Road area also has kosher food stores, restaurants, and gift shops.

The Laura and Alvin Siegal College of Jewish Studies, formerly housed on Taylor Road, moved to a new building in Beachwood, which it shares with the Agnon School, a community day school. This campus also houses the Mandel Jewish Community Center in its only remaining building now that the Cleveland Heights JCChas been sold; the eastern satellite of Temple-Tifereth Israel; and the new (2005) Milton and Tamar Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage, a collaborative effort of the Temple-Tifereth Israel, the Jewish Community Federation, and the Maltz family, with many artifacts and documents from the Cleveland Jewish Archives collections of the Western Reserve Historical Society. Slightly to the east in Pepper Pike are B’nai Jeshurun and the Gross Schechter School, both associated with the Conservative movement.

Despite continued strength in the inner suburbs, buildings housing Jewish institutions continue to be constructed in suburbs farther east, with a new branch of the Cleveland Hebrew Schools under construction in Solon, Montefiore Home’s assisted living facility in Bainbridge, along with several small congregations.

Mt. Sinai Hospital, after a near century of providing outstanding health care, research breakthroughs, and opportunities for Jewish physicians, was sold to a for-profit health care system that eventually dissolved the hospital. Jewish physicians and scientists have increasingly made their mark at the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and Case Western Reserve University, where earlier Albert *Michelson (1852–1931) won a Nobel Prize in 1907, and Harry Goldblatt (1891–1977) made notable contributions in the field of renal hypertension. Philanthropic dollars have constructed major buildings at each of these facilities, including the Lerner Research Building and the Sam and Maria Miller Emergency Room at the Cleveland Clinic, the Mandel School of Advanced Social Services, the Peter B. Lewis Building of the Weatherhead Business School and the Wolstein Research Building at Case Western Reserve University, and the Horvitz Tower at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital. In the business world, the Stone and Weiss families continue to lead the American Greetings Corporation, the Ratner family heads Forest City Enterprises, a major construction firm, and Peter Lewis’ Progressive Insurance Company employs over 14,000 workers.

In politics, Beryl Rothschild, Harvey Friedman, and Merle Gordon served as mayors of University Heights and Beachwood; in addition to Howard Metzenbaum in the U.S. Senate, Eric Fingerhut has represented the district in Ohio state government. Milton A. Wolf served as ambassador to Austria during the Carter administration.

Contributions to the Arts and Popular Culture

Cleveland Jews have enriched the cultural life of the community in many areas. In literature, Martha Wolfenstein, Jo *Sinclair, Herbert *Gold, Jerome Lawrence, and more recently, Alix Kates Shulman, Susan Orlean, and Harvey Pekar worked in Northeast Ohio. David Dietz was a noted science writer, while David B. Guralnik (1920–2001) was the chief editor of Webster’s New World Dictionary for more than 40 years. Abraham H. Friedland, Libbie Braverman (1900–1990), and Bea Stadtler (1921–2000) wrote in the field of Jewish education. In the visual arts, Max Kalish (1891–1945), William *Zorach (1887–1966), and Louis Loeb were sculptors, Abel and Alex Warshawsky were painters, and Louis Rorimer (1872–1939) was influential in interior design. In music, Nikolai Sokoloff (1886–1965) was the first conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra; composer Ernest *Bloch (1880–1959) was the first director of the Cleveland School of Music and Arthur *Loesser(1894–1969) and Beryl *Rubinstein (1898–1952) led the piano departments at the school. Cleveland has also been called the birthplace of rock and roll music, beginning with the 1952 Moondog Coronation Ball, led by disk jockey Alan *Freed (1922–1965). Dorothy Fuldheim (1893–1989) was the first woman in America with her own television news program. Some Cleveland Jewish individuals and families have long been interested in professional sports. Max Rosenblum founded a professional basketball team in the 1920s. Members of the Gries family, Art *Modell, and Alfred Lerner all owned or shared in the ownership of the Cleveland Browns football team.