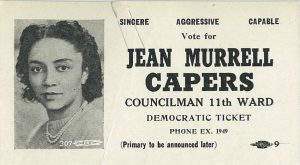

1948 photo (CSU)

Jean Murrell Capers by Marian Morton

Jean Murrell Capers (1913-2017) met head-on the challenges of being both female and black by maintaining her outspoken political independence. The daughter of teachers, she went to Western Reserve University on a scholarship, one of the university’s few black students at the time. She earned a degree in education and taught briefly before getting her law degree from Cleveland Law School. She passed the Ohio Bar in 1945 and was appointed assistant police prosecutor by Mayor Thomas A. Burke in 1946. “[A]nother first for Negro women,” the Cleveland Call and Post announced proudly. [16]The newspaper later applauded Capers as the one of several “lady lawyers [who] bring beauty [and] brains” to the local legal community. An accompanying photo shows a stylish Capers, smiling mischievously. [17]

Capers made her first foray into partisan politics in 1943, staging an unsuccessful write-in campaign for City Council. She also ran unsuccessfully for Council in 1945 and 1947. Like Cermak, she early gained the support of organized women’s groups, and in 1949, she got one of her few political endorsements from the Glenara Temple of Elks, of which she was a member. “[I]t is high time that Negro womanhood took its place in the sun of city politics,” said Republican leader and temple member, Lethia C. Fleming. [18] In 1949, on her fourth try, Capers became the first black woman to be elected to City Council and the first Democrat to be elected from what had historically been a Republican ward.

Her four subsequent elections to Council reflected her ability to organize her ward and get out her supporters, doubtless impressed by her education, her political skills, and her glamorous appearance. Capers fought for a swimming pool for her ward’s children and offered a prize for the neighborhood’s cleanest yard.

But she also sparked plenty of controversy and made plenty of enemies. She joined forces with Council member Charles V. Carr in an unsuccessful effort to make the possession (as opposed to the sale) of policy slips legal despite police efforts to crack down on the numbers racket. [19] And despite the opposition from local pastors, she got a license for a local bingo parlor. She criticized Cleveland’s ambitious slum clearance program: “In every instance since urban renewal began, the city has created more problems than it has cured. This is reflected in increased crime and lower sanitation standards.”[20] (Its critics often referred to urban renewal as “Negro removal.”)

Her opponents alleged that she had ties to rackets figures and pointed to her poor attendance record at Council meetings. There were also allegations of voter fraud in her ward in 1952 and 1953. In 1956, she was the only black member of Council to oppose the fluoridation of city water, further estranging her from the Democratic majority. [21]

Even though it had earlier praised her, Capers’ most outspoken critic became the Cleveland Call and Post, the city’s African-American and Republican newspaper, which accused her of being a lazy Councilman and a “wholly irresponsible person.” [22] She was a “vicious, skilled campaigner,” the paper claimed, whose sex “protected her from retaliation in kind.”[23] Her sex did not protect her from savage attacks by the paper – for example, for her opposition to the appointment of Charles P. Lucas, a black, to the Cleveland Transit Board in 1958: “the odor of selfish irresponsibility and putrid demagoguery … marked the conduct of Mrs. Jean Murrell Capers,” the paper spluttered. [24] Everyone wanted her out of office except her constituents.

By 1959, however, although she was chairman of Council’s powerful planning committee, Capers had lost her Council seat to James H. Bell, the candidate endorsed by local Democrats. Bell “ has retired, at least temporarily, one of Cleveland’s most colorful and successful political demagogues …. [who] was possessed of a vibrant sort of feminine attractiveness, an excellent family background, and a razor sharp mind, ” wrote the Call and Post. [25] Capers unsuccessfully filed suit in Common Pleas Court to set aside Bell’s “fraudulent victory.” [26] Undiscouraged, she ran unsuccessfully in 1960 in the Democratic primary for state Senate in a large field that included Carl Stokes, and in 1963, she lost a primary race for her old Council seat.

In 1965, Capers and her League of Non-Partisan Voters organized the movement to draft Stokes to run as an independent mayoral candidate, a race which he lost. Only two years later, however, the league supported Republican Seth Taft when he ran against Stokes for mayor. Capers minced no words when she explained league’s about-face: “Mr. Taft has qualities superior to those of his opponent and has the broad personal knowledge necessary to administer the complex affairs of the city. Stokes knows nothing about anything and is far too superficial in our judgement to serve as mayor. Carl Stokes especially lacks the knowledge and understanding necessary to solve this city’s crisis in human relations.” [27] Capers subsequently acted as the lawyer for Lee-Seville homeowners who fought off Stokes’ plan to locate public housing in their neighborhood. In his embittered autobiography, Stokes called her “one of the brightest politicians ever to come out of Cleveland” but also accused her of being a hustler who supported him in 1965 only to get herself back into politics. [28]

In March 1971, Capers decided to run as an independent in the mayoral primary. She had joined the new National Organization for Women and hoped to win support from the emerging woman’s movement. In mid-summer, she discovered that she had missed the Board of Elections filing date for independents but persuaded a federal judge to overturn this early filing date. The date became a moot point since she did not get enough valid signatures on her petition and was disqualified from the mayoral race. Thanks to a divided Democratic Party, Republican Ralph Perk was elected mayor.

By 1976, Capers had become a Republican herself, and her former nemesis, the Call and Post, endorsed her candidacy for Juvenile Court Judge. She lost this race, but Republican Governor James A. Rhodes appointed her to a municipal judgeship in 1977, a position she held until her retirement in 1986. Reflecting on her long, difficult political career, Capers pointed to her double handicaps of race and gender, maintaining that her “detractors resented her not just because she was a black woman but because she was an educated black woman. ‘They still had the concept that the only place for a Negro woman was on her knees scrubbing the floors. If I had been a dumb Negro woman, I would have gotten along much better.’”[29]

In recognition of her long, difficult political career, Capers earned many professional honors. These include the Norman S. Minor Bar Association Trailblazer Award and induction into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame.

This essay is part of a longer piece written by Dr. Marian Morton, here