Frederic C. Howe: Making Cleveland the City Beautiful (Or At Least, Trying)

by Marian Morton

In 1894, Frederic C. Howe chose Cleveland as a place to live and work: “It had possibilities of beauty,” he recalled, and “stretched for miles along the lake front.”[i] For the next decade and a half Howe, in concert with a gifted group of civic leaders, pursued those possibilities, going beyond the conventional definition of the city beautiful – grand public buildings in grand public spaces. For these men, the city beautiful meant not only the handsome buildings clustered around the mall that Clevelanders call the Group Plan, but a city that was humane, democratic, and equitable.

Howe himself was a writer, not a politician (he served only two unsatisfying terms as an elected official). Part muckraker, part civic booster, and always the Progressive reformer, Howe was the author of 17 books and innumerable articles for local and national media. Two of these especially – his autobiography, Confessions of a Reformer (1925), and The City: The Hope of Democracy (1905) – paint compelling, although partisan, pictures of Cleveland when it was declared “the best governed city” in the country.

Born in 1867 and educated at Allegheny College in the small, conservative town of Meadville, Pennsylvania, Howe had hoped to become a journalist and earned a Ph.D. in 1892 from Johns Hopkins University, one of the country’s first graduate schools, so that he could write for the New York Times or some comparably prestigious newspaper. But despite his degree – or because of it -, Howe could not land a newspaper job. Discouraged, he studied for and passed the bar exam (with significant help from his graduate work in history) and moved to Cleveland.

Howe’s Cleveland was a promising place with a population in 1890 of 261,353. The industrial giant led in the production of iron and steel, ships, and soon, automotive parts. On the southeast quadrant of its first park, Memorial Square (now Public Square), stood the newly completed Soldiers and Sailors Monument, honoring Clevelanders who fought for the Union during the Civil War; across Superior Avenue loomed the handsome red sandstone Society for Savings bank (now part of Key Center), designed by the Chicago firm of Burnham and Root. Just to the east of Memorial Square was the Euclid Arcade, completed in 1890. Its glass-roofed court of shops and offices became the glittering symbol of the city’s prosperity; Clevelanders later boasted that it was the country’s first indoor shopping mall. Wealthy philanthropists added to the city’s beautiful parks. In 1882, Jeptha H. Wade had given to the city 64 acres of parkland in what is now University Circle. William J. Gordon’s generous gift of his estate in 1894 created Gordon Park along the lake on the east side. To celebrate the city’s centennial in 1896, John D. Rockefeller would donate the land along Doan Brook that tied the two parks together; Martin Luther King Boulevard (formerly Liberty Boulevard) runs through Rockefeller Park. The city bought Jacob B. Perkins’ lakefront property in 1894 to create Edgewater Park on the west side.

If these possibilities inspired Howe’s admiration, the city’s realities inspired his desire to reform it. When Howe arrived, the city was still in the throes of the country’s worst depression. In 1893, the public poorhouse, the Cleveland Infirmary, was full. Outside its doors, more than 4,000 men, women, and children, who had shelter but could not support themselves or their families, lined up to receive what was then called “outdoor relief”: groceries, soap, shoes, and railroad tickets out of town. Less than 25 percent of the recipients were native-born; the rest were immigrants who had poured into the city from northern and southern Europe in search of jobs in Cleveland’s factories and mills. [ii] Last to arrive, they were first to be fired when the economy turned sour. Compounding the city’s difficulties were political corruption and selfish entrenched wealth. Howe claimed that Cleveland councilmen and mayors like Robert E. McKisson and “Honest John” Farley were in the pockets of local businessmen who sought public favors; Howe called incumbent politicians “spoilsmen, bosses, grafters.” [iii] Moreover, many Clevelanders who had gotten rich by arriving early and acquiring substantial property did not serve the public but served themselves at the public expense. A good example, Howe maintained, was Mark Hanna. A Republican kingmaker generally credited with putting his friend William McKinley in the White House in 1896 and 1900, Hanna served in the U.S. Senate, 1897-1904. As the owner of Cleveland’s largest streetcar company, Hanna often did battle with Johnson. Although Howe came to like Hanna personally, Howe also claimed that the Republican controlled the banks, the press, and the Ohio legislature, enriching “himself without compunction, believing that the State was a businessman’s State” [iv] that existed solely to enrich corporate interests at the expense of the public.

Howe joined the law firm of Harry and James Garfield, sons of the assassinated President James Garfield. Although Howe claimed to work “listlessly” at the law, the Garfields made him a partner in the firm in 1896 and despite their political differences, became his close personal friends. Howe lived briefly at Goodrich House, a social settlement established by philanthropist Flora Stone Mather. The middle-class, well educated young settlement house residents like Howe saw firsthand the economic and social problems created by and for urban newcomers and had the education and the political and financial savvy to search for solutions. At Goodrich House, for example, were born Cleveland’s Legal Aid Society (Howe was one of its incorporators), the Consumers League of Ohio, and the Cleveland Music School Settlement. Howe, however, claimed not to enjoy visiting nearby tenements or socializing with immigrants. Nor did he enjoy his work with the Charity Organization Society, which provided private relief to the city’s indigent, believing the organization both uncharitable and ineffective.

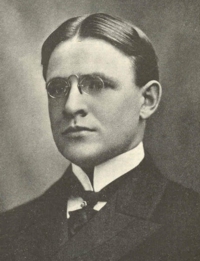

More to Howe’s liking was the Municipal Association (later the Citizens League of Greater Cleveland), foes of political corruption and advocates of good government. Howe became the association’s secretary and in 1901, ran for Cleveland City Council on the Republican ticket. He enjoyed speaking in saloons and having his photograph tacked to telegraph poles and promised that ‘the old gang would be cleaned out,” [v] replaced by men like himself, incorruptible Republicans. Contemporary photographs show a handsome, serious young Howe, high-collared, bespectacled, the epitome of the scholar in politics.

Yet Howe found himself increasingly drawn to Democrat Tom L. Johnson, recently a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and in 1901 a candidate for mayor of Cleveland. Johnson had made his fortune as a streetcar monopolist; he retired from business when he entered public service and lived in a Romanesque Revival mansion on Euclid Avenue, Cleveland’s Millionaires’ Row. Howe admired Johnson’s lively political style – tent meetings at which ordinary citizens were encouraged to challenge him – and even more, his simple political creed: “The trouble was not with the people, it was poverty… Most people would be good if they had a chance. ” Politics should create that chance. [vi] Johnson gave Howe his most enduring political lessons; and Howe praised his teacher: “I had greater affection for Tom Johnson than for any man I have ever known… He was ‘Tom’ to everyone in Cleveland … Even the children on the streets greeted him as ‘Tom.’” [vii]

Both men were elected in 1901. Johnson won his first of four terms as mayor. Howe won his one term in city council. He lost the 1903 election when he ran as an independent. Thereafter, he joined the Democrats, Johnson, and his able advisers, including Dr. Harris R. Cooley, Director of Charities and Corrections, as well as the pastor of Johnson’s Disciples of Christ congregation; Peter Witt, former labor organizer, advocate and practitioner of free speech, who became Johnson’s city clerk; Newton D. Baker, Howe’s fellow graduate student at Johns Hopkins, who became Johnson’s law director, then mayor of Cleveland (1912-1915), then Secretary of War during the Woodrow Wilson administration.

In his usually self-deprecating autobiography, Howe took credit – with his friends – for first imagining Cleveland’s Group Plan even before he ran for office. The plan remains Cleveland’s clearest example of the city beautiful movement, the country’s response to rapid, unplanned, ugly urban growth. Howe’s vision was inspired in part by Daniel Burnham’s White City, a magnificent cluster of buildings grouped around an open mall, at the Chicago Exposition of 1893; Burnham became one of the architects of Cleveland’s Group Plan. Crowded tenements and sleazy commercial structures to the north of Public Square were razed to make room for the handsome Beaux Arts buildings. (In the 1960s, this would have been called “urban renewal.”) In 1905, Howe boasted that “no other city in America has projected as well as assured the carrying out of the systematic beautification of the city on so splendid a scale as has Cleveland.” [viii] The building began in 1910 with the Federal Court House, followed by Cuyahoga County Court House (1912), Cleveland City Hall (1916), Public Auditorium (1922), Cleveland Public Library (1925) and finally, the Board of Education (1930). Although designed by several distinguished architects, the buildings are of uniform size and height, sited on an impressive mall, originally grass-covered and tree-lined, that faced north to Lake Erie. Clevelanders believe this to be “the earliest and most complete civic-center plan for a major city outside of Washington, D.C.”[ix]

Other beautification projects initiated by Johnson and his political advisers included the expansion of the city’s existing park system and the addition of public baths, sports fields, tennis courts, playgrounds and skating rinks. After his marriage, Howe lived on Glen Park Place (now East 86th St.), near a creek that led into Doan Brook and within an easy walk of Wade and Rockefeller Parks. “On Saturdays and Sundays,” Howe reported, “the whole population played baseball in hundreds of parks laid out for that purpose. Cleveland became a play city,” attracting workers and businesses. [x] Johnson famously removed the “Keep off the grass signs” from public lawns, symbolizing the administration’s desire to make public spaces friendly as well as beautiful.

The city should be not only beautiful, Howe believed, but humane, caring for even its humblest residents. The Johnson administration provided more generous outdoor relief and replaced the Infirmary with Cooley Farm on city property in Highland Heights, which sheltered mostly the elderly. Children who ran afoul of the law were judged in one of the country’s first juvenile courts. Hudson Boys Farm replaced an older reformatory for male juvenile delinquents. “At this farm-school no brand attaches; it leaves no scar and saves self-respect,” Howe maintained. [xi]

A city should be open and responsive to its citizens, encouraging them to make important decisions, and it should have the power to make important decisions that bettered their lives. To achieve this, Johnson and Howe advocated municipal home rule. Howe served one term in the Ohio Senate State, 1906-1908, where he unsuccessfully worked for home rule legislation that would have allowed cities to call constitutional conventions and change their form of government, raise their own revenues, and to own street railways and other utilities. (He did succeed in getting passed legislation that allowed Cleveland to proceed with the Group Plan.) In 1912, Johnson’s protégé, Newton D. Baker, helped to write the Ohio constitutional amendment that allowed home rule.

In pursuit of a political system as open as Johnson’s tent meetings, Howe and Johnson endorsed the initiative, referendum and recall, and votes for women. Howe credited his wife, Marie Jenney Howe, with converting Johnson to woman suffrage. “Mr. Johnson, you who are democratic in everything else, why are you not democratic about women? Why do you not believe in woman suffrage?” [xii] According to Howe, Johnson enthusiastically supported suffrage from then on. Although Cleveland women also rallied to the cause, the city did not play a leading role in the suffrage movement that culminated in 1920 with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Most important, a city should be equitable. Like his mentor Johnson, Howe believed that unjust economic institutions explained urban problems: “The worst of the distressing poverty, as well as the irresponsible wealth, is traceable to economic institutions, to franchise privileges and unwise taxation.” [xiii] Johnson and Howe proposed two solutions: the single tax and public ownership of utilities.

Johnson had become a convert to the single tax when he read Henry George’s Progress and Poverty; Johnson then converted Howe. The single tax would replace all other taxes and would be levied on unimproved land – not on improvements like homes or businesses: for example, vacant land on or around Public Square, whose value would be increased not by its owner’s efforts or investments but by improvements on neighboring properties. This tax would discourage “privilege,” wealth created by the acquisition and monopoly of land. The single tax would be levied by the city, rather than by the state or federal government, enhancing the power of local government and its citizens’ interest in it. The single tax was an attractive idea in an era of great urban growth when land ownership was in fact the single most important source of wealth. In his autobiography, Howe used as significant examples of land acquisition two early suburban allotments: Euclid Heights and the Van Sweringens’ Shaker Village. [xiv] (He did not mention that Patrick Calhoun, the developer of Euclid Heights, went bankrupt in 1914; nor could he have known that the Van Sweringens would also go bust during the Depression. )

The dream of a single tax was not achieved then or later, but the reform of the tax structure was a victory in which Howe played a part. In 1909, he was elected to the Tax Commission, charged with the re-appraisal of all properties within the city. The commission employed an expert tax-appraiser who facilitated a more equitable tax process: “The home-owner and the poor were relieved of millions of dollars of taxes that were placed on down-town property, manufacturing sites, railroad rights of way, and the water front,” Howe maintained. ‘It was the most satisfying experience of my political life.” [xv]

Even more contentious was the issue of publicly owned utilities. Johnson and Howe were not socialists, as their opponents often charged, advocating municipal ownership only of utilities. Utilities, they believed, were easily monopolized, and their owners could charge exorbitant rates. Utilities required franchises from public officials, creating endless possibilities for bribery. Howe was shocked to discover that his own election to City Council had been financed by the gas company. If privately owned utilities could survive only by bribing officials and corrupting government, then utilities should be owned by the city, Howe decided. [xvi] The Johnson administration’s fight for a publicly owned streetcar triggered “a ten years war,” class warfare that pitted “men of property and influence” against “the politicians, immigrants, workers, and persons of small means.” [xvii] A city-owned streetcar line would avoid such corruption and could charge its riders less.

Since the state did not allow the city to own utilities, the Johnson administration established a private holding company that would lease and operate several of the small streetcar lines; the Municipal Traction Company had a three-cent fare and Howe as its vice-president. However, there was a violent strike against the company , secretly supported by Johnson’s foes, according to Howe,[xviii] and a subsequent referendum did not endorse the company. In 1910, Judge Robert Walker Tayler created one privately-held railway company with a three-cent fare and public oversight.

The dream of a public transit system was not achieved until 1942 when private investors decided that streetcars were no longer profitable. Johnson’s administration also wanted the city to own and operate an electric plant. The city built a public plant in 1914. It has survived several attacks by private utility companies and is now called Cleveland Public Power.

In 1909, Johnson was defeated at the polls by voters perhaps weary of these controversies. His ill health worsened by this loss, he died in 1911.

Over Johnson’s objections, Howe and his wife had left Cleveland for New York City in 1911, but Howe did not leave politics or abandon reform. In New York, he became director of the People’s Institute, a public forum, where he met many of the leading figures of the Progressive movement. (Marie Jenney Howe became a leading feminist; her reputation now outstrips that of her husband.) When Woodrow Wilson, one of Howe’s professors at Johns Hopkins became President, he appointed Howe Commissioner at Ellis Island where he had the unhappy job of watching over hundreds of temporarily detained immigrants, made even more unhappy by the deportation of persons accused of being spies and subversives when the United States entered World War I in 1917. Howe also accompanied Wilson to Versailles to advise on the treaty that ended the war. During the 1920s, when Progressive reformism seemed moribund, Howe became active in the Conference on Progressive Political Action, formed to further the cause of labor and farmers. Many of the Progressive goals were achieved during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; Howe also served in Roosevelt’s administration as consumer counsel for the Agricultural Adjustment Act. He died in 1940. Howe recalled his years in Cleveland as the “crusade of my youth, the greatest adventure of my life.[xix]

This is a different city than the one Howe worked and lived in. In 1910, shortly before Howe left, Cleveland was the sixth biggest city in the country with a population of 560,663. (Its population would peak in 1950 at 914,808.) Almost three quarters of the 1910 residents were immigrants or the children of immigrants. Newcomers from southeastern Europe – Italy, Russia, Hungary – had joined the large German and Irish communities. Slightly more than 8,000 Clevelanders (1.5 percent of the population) were African American. A century later, the city has lost tens of thousands of the factory jobs that had attracted these immigrants. Cleveland’s biggest private employers are not heavy industry but the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals. Cleveland’s population has dropped to 396,815, thanks in large part to the federal highways that facilitated out-migration to suburbs south, east, and west.

Yet Cleveland remains the economic and cultural heart of northeast Ohio. And Clevelanders today – whether they live in the city or not – have inherited the tangible legacy of Howe’s youthful crusade: a publicly owned municipal light plant and transit system, home rule (although less of it than Cleveland officials would like), parks, pools, playgrounds, and the Group Plan. They inherit as well a city that still stretches along the lake with the possibilities of beauty that inspired Howe and his peers to make Cleveland the city beautiful. Or at least, try.

[i] Frederic C. Howe. Confessions of a Reformer (Kent, Ohio and London, England: Kent State University Press), 73.

[ii] Annual Report (Cleveland: City of Cleveland, Department of Charities and Corrections 1893), 78.

[iii] Howe, Confessions, 100.

[iv] Ibid, 151.

[v] Ibid, 91.

[vi] ibid, 93.

[vii] Ibid., 127.

[viii] Howe, The City: The Hope of Democracy (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 243.

[ix] David D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, editors, The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996), 672.

[x] Howe, Confessions, 109.

[xi] Howe, The City, 228.

[xii] Howe, Confessions, 137.

[xiii] Howe, The City, ix.

[xiv] Howe, Confessions, 214-217.

[xv] Ibid., 230.

[xvi] Ibid., 107.

[xvii] Ibid., 115.

[xviii] Ibid., 125.

[xix] Ibid., 115.