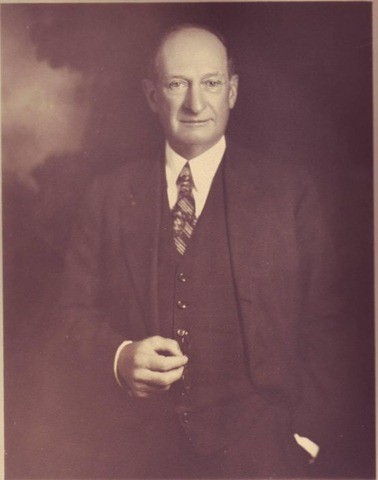

Maurice Maschke – The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland

by Brent Larkin

More than 75 years after his death, memories of Maurice Maschke linger still in the minds of the precious few who remember a political boss whose power influenced almost every aspect of life in Cleveland.

“I was a young boy who grew up in his neighborhood,” Forest City Corp. executive Sam Miller recalled of the legendary Republican leader. “I remember well he was the person everyone went to if they wanted something done.”

Hall of Fame journalist Doris O’Donnell’s mother was a Democratic ward leader for party boss Ray T. Miller – Maschke’s longtime political rival.

“On Sundays, we had these large family dinners at our home in Old Brooklyn and invariably there would be talk about city politics, about Miller and Maschke,” said O’Donnell. “They were both very competitive – and very smart.”

Longtime Ohio Republican Party chair Bob Bennett cut his teeth in Cleveland politics during the 1960s. Back then, Bennett said the Republican old timers regularly spoke of Maschke in reverential terms.

“He set the standard for political bosses, for how to obtain power and use it effectively,” said Bennett. “He made things happen. And, most importantly, he knew how to choose the right candidates and win elections. After all, that’s what politics is all about.”

It is indeed.

And no one in Cleveland ever did it better than Maurice Maschke.

****************************

Born in Cleveland in 1868, Maschke grew up in the predominately Jewish neighborhood of lower Woodland Ave., a few miles southeast of downtown.

The son of a relatively successful grocer, Maschke was a bright young boy – so bright he was schooled at the prestigious Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and Harvard University near Boston.

Graduating from Harvard in 1890, Maschke returned to Cleveland where he studied to be a lawyer. While reading law, he landed a job as a clerk in the county courthouse, a place teeming with aspiring politicians.

It was around this time that Maschke befriended Robert McKisson, a rising star in city politics. Maschke signed on as a precinct worker in the McKisson political organization. In 1894, McKisson was elected to City Council. A year later, he was elected mayor.

That election increased Maschke’s stature within the Republican Party. And it enabled him to secure an important job in the county recorders office.

Maschke, it seemed, was on his way.

But McKisson soon clashed with Marcus Hanna, the Cleveland industrialist who in 1900 would engineer William McKinnley’s election as president. Hanna was, at the time, the nation’s most powerful political insider and McKisson’s falling out with Hanna contributed to his defeat in the mayoral election of 1899.

That defeat could have slowed Maschke’s political ascent, but by then the young East Sider no longer needed the support of a powerful political patron. He had figured how to advance on his own.

Maschke formed an alliance with Albert “Starlight” Boyd, the city’s black political boss, that served them both well. He also befriended Theodore Burton, an ambitious young congressman with a big Republican following.

In 1907, Burton unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Mayor Tom L. Johnson. But in early 1909, the legislature appointed Burton to the U.S. Senate. Maschke became Burton’s political eyes and ears back home.

Many now considered Maschke the city’s most powerful Republican operative. Later that year, he would prove them right.

After eight years in office, Tom L. Johnson had won the reputation as perhaps the nation’s greatest big city mayor. To this day, the progressive Democrat is revered for building an affordable, citywide transit system, providing low-cost electricity to residents through construction of a municipal light plant, and the opening of dozens of new parks.

But as the 1909 election approached, Maschke boldly predicted he had a candidate who could beat Johnson. Most regarded the claim as political puffery – especially when they heard Maschke’s candidate was Herman Baehr, the bland and inarticulate county recorder.

Nevertheless, Maschke was adamant. “Baehr will win,” he insisted. “Johnson has been mayor for eight years. That’s too long.”

True to form, Baehr proved to be a horrible campaigner. Johnson was so unimpressed by his opponent that, three days before the election, he left town.

He should have stayed. On Election Day, Baehr won decisively. Maschke, who became county recorder when Baehr vacated the job, was now the town’s preeminent political figure.

Next, Maschke would take his act to the biggest political stage of all.

At the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, President William Howard Taft was challenged by former President Theodore Roosevelt. As the convention opened, it appeared Taft had squandered his incumbent’s advantage – losing 9 of the 12 statewide primaries to Roosevelt, including his home state of Ohio.

But 100 years ago party bosses had a greater say in the presidential nominating process than rank and file voters. And in Chicago that year, perhaps no party boss had more clout than the Republican from Cleveland. When the roll was called, Maschke played a key role in Taft’s nomination.

That November, Taft lost the general election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, but not before he appointed Maschke to the coveted post as Northeast Ohio’s customs collector. It was Boss Maschke’s last public job.

****************************

By 1920, Maschke had formally taken charge of the entity he had, in actuality, controlled for a decade – the county Republican Party. He had also established a law firm, that would eventually make him a wealthy man.

In 1924, Cleveland switched to a city manager form of government – with the job being filled by William Hopkins, Maschke’s close friend. Hopkins was charismatic and visionary. He championed construction of a huge stadium on the lakefront and purchased land from Brook Park to build an airport.

But Cleveland’s population was changing. A steady influx of European immigrants added to the Democratic Party’s growing numbers. And Democratic Party chair Ray T. Miller, who doubled as county prosecutor, was shrewdly taking advantage of that growth.

Compounding Maschke’s political problems were corruption charges – and some convictions – of Republican party operatives. Maschke himself was charged for his alleged role in a scandal involving county government. But the case against him was weak, and Maschke was acquitted.

Nevertheless, criticism of the chairman was growing – even from some Republicans. Near the end of the 1920s, Maschke’s power at home was waning.

But on the national stage, Maschke summoned up one more grand performance. In 1928, he was a leading supporter and valuable political strategist to Herbert Hoover’s successful presidential campaign.

Once again, Maschke had a friend in the White House. At home, however, problems continued.

But by the late 1920s, Maschke and Hopkins had a huge falling out. Some speculated Maschke resented Hopkins’ popularity. Another theory held Maschke thought Hopkins didn’t do enough to support Maschke’s friends, the Van Sweringen brothers, during construction of the Terminal Tower.

Whatever the cause of the rift, Maschke, as usual, prevailed. In 1930 members of City Council, saying Hopkins had become power-hungry, fired him. Not long after, during an appearance at the City Club, Maschke said he had merely “put Hopkins back on the street where I found him.”

*********************

It is fair to wonder how Maschke, a Jew in a city where Jews represented only a fraction of the population, was able to dominate city politics for more than a two-decades-long period. The answer requires some educated speculation, but the answer is probably a combination of some or all of these factors:

Maschke’s religion was probably unknown to many, as it was hardly a common Jewish surname. What’s more, at the time, Republican rank and file were viewed as more progressive and open- minded than their working class Democratic counterparts.

And since Maschke never sought high office, his religion and ethnicity was never really a factor with the electorate. Had he run for congress or mayor, voters might have paid more attention to his background and beliefs.

Then, as now, results are what matter most to candidates and party operatives.

Maschke, however, was hardly the first political boss who was intelligent and understood how to win elections. What differentiated him from the others was his civility, honesty, perhaps even a sense of decency.

On that night of Maschke’s death, Roelif Loveland, considered one of the two or three greatest Cleveland journalists of all time, wrote of Maschke:

“To think of him – and we who knew him are not likely to forget him in a hurry – to think of him is to think of a man who was kind and gracious; who loved this city and his family and his party and truth and personal decency. To be sure, he gave the city about what its citizens wanted. If they wanted the town cleaned up, it was cleaned up. If they wanted it less rigid, it was less rigid.”

For all of Maschke’s endearing traits, what differentiated him from so many in public life was the well-rounded nature of his life. In the very first paragraph of an editorial following his death, the Plain Dealer noted his enormous political accomplishments, but also noted Maschke was a cultivated gentleman with many friends, lover of the classics, expert at bridge, devotee of golf – a polished, suave and delightful personality.

Maschke was hardly Cleveland’s last successful political boss. Nor is he the most renowned. That title probably belongs to Marcus Hanna.

But, for a time, Maurice Maschke probably accumulated and wielded more political power than any local leader before or since.

When he died of pneumonia on Nov. 19, 1936, the Plain Dealer’s coverage included 10 front page photographs and an obituary that started on Page One and ran for five pages inside.

In his tribute, Roelif Loveland recalled that during tense moments on election nights Maschke would seem to sometimes growl at his assistants.

“They pretended to be frightened” wrote Loveland. “But they weren’t.” Why?

“Because they loved him.”

To read more about Maurice Maschke, click here

Brent Larkin joined The Plain Dealer in 1981 and in 1991 became the director of the newspaper’s opinion pages. In October 2002 Larkin was inducted into The Cleveland Press Club’s Hall of Fame. Larkin retired from The Plain Dealer in May of 2009, but still writes a weekly column for the newspaper’s Sunday Forum section.