Norman Krumholz

Norman Krumholz

Rebel with a Plan: Norm Krumholz and “Equity Planning” in Cleveland

By Robert Brown

When Norman Krumholz arrived in Cleveland in 1969 to take the job of City Planning Director under Mayor Carl Stokes — the first black mayor of a major American city — the city was in the midst of a historic loss of population and jobs and was still reeling from the racial unrest that led to what became known as the Hough “riots” of 1966 and the Glenville “riots” of 1968.

As the 41-year old Krumholz and his band of newly-hired, social activist planners considered creating a new comprehensive plan for Cleveland, they found that the traditional tools and techniques of city planning – including land use plans, roadway plans and the like – did not adequately address the issues facing the city at that time.

In the words of Krumholz and his colleagues: “….the problems of Cleveland and its people have less to do with land uses, zoning, or issues of urban design – the traditional domain of city planners – and more to do with personal and municipal poverty, unemployment, neighborhood deterioration and abandonment, crime, inadequate mobility, and so on.”[1]

Krumholz and his planners then set about the task of analyzing the issues facing Cleveland and crafting recommendations and plans to address those issues. Their approach to this task differed from the textbook approach taken by most planners. The work of Cleveland’s planners was strongly based in particular ideologies — the ideologies of “equity planning” and “advocacy planning.”

Again in words of Krumholz and his colleagues: “Equity requires that government institutions give priority attention to the goal of promoting a wider range of choices for those Cleveland residents who have few, if any, choices.”[2] [emphasis added]

This was the focus and the mantra of Krumholz and the Cleveland City Planning staff in the 1970’s – advocating for decision-making on projects and programs so as to give priority to meeting the needs of city’s poorest residents, those who have “few, if any, choices,” those who decades later would be called “the least among us” by Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson.

Cleveland’s Policy Plan Report

The work of Krumholz’ City Planning staff culminated (but did not end) in 1975 with publication of the Policy Planning Report, a bold and ground-breaking comprehensive plan that made social policy the centerpiece of Cleveland’s city planning program. Cleveland’s plan quickly took center stage nationally and even internationally in the field of city planning, as it sparked debate over the

appropriate role of the city planner in local government.

Krumholz would argue that “a planner is what a planner does.” In other words, a city planner need not be constrained by the traditionally defined parameters of the profession. This meant that planners in Cleveland could use their skills and talents to tackle issues of poverty and income redistribution, while planners in other cities continued to address more conventional planning issues, such as land use and urban design.

Krumholz elaborated, “Planners may choose to stay within the narrow boundaries of their customary area of expertise, or they may define new roles for themselves. To opt for the former is to risk being relegated to an increasingly marginal position in urban affairs. In choosing to redefine their roles along the lines outlined above, planners may eventually find themselves in positions of leadership in urban government.”[3]

Cleveland’s Policy Plan was an overtly value-driven initiative, advocating for the community’s poorest residents and pursuing the goal of social and economic equity. This form of planning – known as equity planning, along with its companion, advocacy planning – had been the subject of academic treatises, particularly in the pioneering work of Paul Davidoff in 1965, but never had this form of planning been put into full-scale practice until the work of Norm Krumholz and his staff at the Cleveland City Planning Commission. In the words of Davidoff, “Norm Krumholz is a hero to me……..both because of the progressive values he held, and because of his dedication to seeing that they became the foundation on which Cleveland’s development would be based.”[4]

To say that the plan was “value-driven” is somewhat of an understatement, as the plan’s authors found support for their principal goal by quoting the writings of no less than Daniel Webster, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Cleveland Mayor Tom Johnson, Plato and Jesus of Nazareth! The goal that guided the planners’ formulation of policies was stated as follows:

“In a context of limited resources and pervasive inequalities, priority attention must be given to

the task of promoting a wider range of choices for those who have few, if any, choices.”

Policies. The plan proposed policies in subject areas deemed to be particularly critical and timely in Cleveland at that time, always tailored to implementation of the plan’s prime directive. “The Commission is less concerned with the number and specificity of its policies than with the consistency between its policies and its goal,” stated the plan in preface to the presentation of policies.

Also noteworthy was the plan’s declaration that its policies were truly its own. “….the Commission’s policies are not necessarily the policies of those who must decide or of those who have powerful influence over decision-makers. They are not necessarily the policies of the Mayor, of the City Council, or the Chamber of Commerce, or the news media, or a host of other individuals and groups who are important in the decision-making process. They are only the policies of the Commission.”

Although most readers will find nothing extraordinary in the preceding statement, those familiar with the inner workings of local government will see this statement as nothing less than incendiary! Despite the fact that city planning commissions, nationally, are intended to be independent citizen-led bodies, in most cities (including Cleveland) their directors are appointed by the mayor and are seen as the mayor’s representatives. For the mayor’s city planning director to proclaim, in today’s political environments, that his department’s policies may not be those of the mayor would most likely be the last proclamation that director would make as a member of the city administration!

Housing Policies. The plan focused much of its policy development on housing, noting that the City Planning Commission’s ability to affect housing outcomes was greater than was the case with many other subjects of interest to city residents, because of the Commission’s credibility in the field of housing. Among the plan’s housing policy recommendations are the following.

- Subsidized housing should not be concentrated in the City’s most deteriorated neighborhoods. Much more attention should be given to building and leasing low-income housing in good residential areas, particularly in the suburbs. [It was understood by the planners that this policy would not win favor in most suburbs!]

- Greater use should be made of Federal subsidies to housing suppliers to encourage rehabilitation and conservation of the City’s existing housing stock. [The report noted that the city’s population loss and the resulting surplus of housing made production of new housing counter-productive in many cases.]

- The Commission urges the initiation of Federal housing subsidies in the form of direct cash assistance to lower-income families, such as the housing allowance programs currently being studied by HUD. [The report states that these housing allowances would expand choices for low-income families, as opposed to housing development programs that limited choices to the housing produced by those programs. HUD then instituted this program, which became known as “Section 8.”]

- Housing for low-income families should not be developed in large projects built specifically for the poor. Whether leased, rehabilitated or newly constructed, low-income family housing should be in small-scale, scattered-site developments. [The report notes that the practice of building massive housing projects exclusively for poor households severely limits the housing choices available to these residents.]

Transportation Policies. Cleveland’s Policy Planning Report was prepared in an era when the transportation component of most local comprehensive plans focused on identifying high-priority roadway projects for implementation. Not surprisingly, Cleveland’s planners took a very different approach. They pointed to the increasing dominance of private automobiles and the resulting decentralization of development (i.e., sprawl) as a major detriment to the viability of public transit services – thereby reducing mobility for residents who are too poor to afford a car or are unable to drive due to their age or physical ability. In response, the plan recommended the following two key transportation policies, the first of which spoke to the then-imminent regionalization of the City’s transit system.

- Transfer of the Cleveland Transit System (CTS) to a regional transit authority should be approved only if:

- A suitable level of service is established for City residents who are dependent upon public transit for their mobility throughout the metropolitan area.

- Such service is maintained by providing subsidized fares for those City residents who lack regular access to automobiles.

- Transit subsidies are collected in such a way as to avoid placing an additional burden upon those who are least able to pay.

- Construction of freeways and expressways in the City of Cleveland should be approved only if:

- The local (City) share of the cost is waived.

- Annual payments are made to compensate the City for all losses in property and income tax revenues resulting from the improvement. These payments should continue until such time as new tax sources, of similar size, have been created by the improvement.

- Prior to highway development, additional housing units–equal in number to those removed–are provided within the City (preferably through rehabilitation of the existing housing stock). These replacement units should be of approximately the same price or rent level as those being displaced.

Income Policies. Although almost all local comprehensive plans aim to increase prosperity in the local community, those plans typically propose to accomplish this through land use and development actions that can be expected to create jobs. In contrast, Cleveland’s Policy Planning Report, while advocating for local job creation, also took aim directly at opportunities to redistribute income for the benefit of residents at the bottom of the economic ladder. Among the income-related policies recommended were the following.

- Public subsidies and incentives aimed at retaining or creating private-sector jobs in the City of Cleveland should be used primarily to support businesses and industries proving to be viable in the City. [The report discourages use of City subsidies to support firms that are more likely to move out of the city.]

- In all cases where the City is asked to provide support for industrial or commercial development (by assuming a share of the project cost, by granting a tax abatement or by providing other types of financial incentives), and where the benefits to the City are alleged to be the maintenance or an increase in jobs and/or tax revenues, the following information may be required for review by the Commission…….. [The policy then lists information regarding the number of jobs to be created by the project, the number of jobs to be lost without the project, the proportion of jobs expected to be filled by City residents, and the increase or loss in local tax revenues with or without the proposed project. During the administration of Mayor Frank Jackson, these conditions were formalized as “Community Benefit Agreements.”]

- A substantial reduction in unemployment among City residents cannot be achieved solely through the creation of private-sector jobs. Additional jobs in worthwhile public-sector enterprises will also be required. The City should support efforts to provide public service employment for Cleveland residents. [The report recommends consideration of a residency requirement for City employment (later instituted) and advocates federally-funded public service employment programs.]

- To assure all Cleveland residents with household responsibilities an annual income above the poverty level, the Commission supports the following Federal policies:

- Basic allowances (payments made to families with incomes below the poverty level) should vary by region of residencies and should be adjusted periodically as the cost of living changes.

- Benefits should not discriminate against the ‘working poor’–those who work full time but at wages below the poverty level.

What Was Accomplished?

Because Norm Krumholz and his staff at Cleveland’s City Planning Commission were equal parts planning theoreticians and social activists, there was no danger of the Policy Planning Report sitting on the shelf as an accomplishment in itself. Once the department established its goal of providing choices for those who had few, if any, choices, it immediately began taking positions and actions to operationalize that goal in the conduct of its business and in its critiques of projects and programs.

“Too often planners have been content to assume a passive role, never making recommendations unless called upon by more powerful actors. An agency that wishes to influence decisions must often take the initiative. It must seize upon important issues and develop recommendations without prior invitation.”[5] Here, Krumholz’ words describe his philosophy not only during his time as Cleveland City Planning Director but the approach he took to city planning throughout his career. He spoke and operated in the “active voice,” never the “passive voice.”

Power through Information & Advocacy. Despite the boldness of his vision and his passion for the welfare of Cleveland’s poorest residents, Krumholz had no illusions about the power of planners to effect change. He understood that the planner was, in most instances, an advisor, an educator, a cajoler, but not a decision-maker. Just as significantly, however, Krumholz realized that planners have the power to affect the actions of decision-makers by providing insightful information about critical issues and by advocating for the empowerment of citizens and civic organizations seeking to achieve social and economic equity in the community.

As Krumholz wrote in 1975, “…..planners who wish to influence public policy must offer something that decision-makers want and can relate to. What the Cleveland City Planning commission tries to offer is not rhetoric but information, analysis, and policy recommendations which are relevant to political decision-making.”[6]

Cleveland’s city planners did just that during the Krumholz years – preparing detailed research and analysis on such topics as public transit, freeway development, housing markets, commercial tax abatement, and welfare payments. They then used this research to make policy recommendations and to lobby for action on those recommendations. Some of their successes are as follows.

- Transit: led effort to establish low fares, reduced fares for seniors and disabled individuals, and a community responsive transit program as conditions of regionalizing the local transit system

- Land Bank: led effort to pass state legislation that shortened and simplified the foreclosure process for tax delinquent and abandoned property, leading to establishment of Cleveland’s “Land Bank,” which continues to hold and transfer vacant property for community benefit (with an inventory of over 12,000 vacant parcels in 2015)

- Freeway Development: assisted in blocking the proposed Clark Freeway (I-290), which would have displaced 1,400 families on the city’s east side – proposing instead a much less damaging alternative route for the highway (neither of which was built)

- Public Utilities: assisted in saving the City-owned municipal electric utility from takeover by the area’s private electric facility, thereby preserving competition and lower rates in the city

- Regional Planning: worked with Mayor Stokes to restructure the 5-county regional planning agency so that the city of Cleveland’s representation on the board was increased to be proportionate to the city’s share of the regional population – thereby ensuring greater attention to central city issues in the agency’s decision-making

- Neighborhood-Based Planning: advocated for the empowerment of neighborhood-based organizations to take lead roles in planning for their own communities – a model that became the norm for neighborhood planning in Cleveland and in other large cities across the nation

- Development Subsidies: initiated more rigorous evaluations of development subsidy requests to ensure adequate benefits to city residents (although the Commission’s disapproval of a high-profile proposal for Tower City was rejected by a 32-1 Council vote, with the Council President calling the Commission a “bunch of baboons” and demanding Krumholz’ resignation)

In 1982, looking back on his ten years at the helm of the Cleveland City Planning Commission, Krumholz described the power available to planners as follows. “The only legitimate power the planner can count on in such matters is the power of information, analysis, and insight, but that power is considerable when harnessed to an authentic conceptualization of the public need.”[7]

Long-Term National Impacts. Today, forty years after adoption of Cleveland’s equity-based Policy Planning Report, what can be said about the long-term and national impacts of Cleveland’s experiment with equity planning? Krumholz himself has not been particularly sanguine about the impact of his work in Cleveland on the profession of city planning, stating, “How did our work in Cleveland affect the work of other practicing city planners? Probably not to any great degree, so far as I could tell. Our model, after all, asked city planners to be what few public administrators are: activist, risk-taking in style, and redistributive in objective.”[8]

Others (including this author) would choose to differ. The work of Norm Krumholz and his pursuit of equity planning in Cleveland reverberated loudly throughout the city planning profession during the 1970’s and continues to be taught in planning schools across the country to this day. Whether or not equity planning took precedence in the work of other city planning departments as it did in Cleveland, there is no doubt that the concept of equity planning entered the world-view of countless thousands of city planners as a result of Krumholz’ work in Cleveland.

No longer could a city planner carry out the plans of developers and politicians without at least pausing to consider its impact on a community’s poor and disenfranchised residents, as well as whether the expenditure represented the community’s best use of scarce public funds.

For many of us in the city planning field, Krumholz has been that small voice in our heads reminding us of why we entered the field – namely, to help create a better world and to create a better quality of life for those who are sometimes left behind by what others have defined as progress. We could choose to ignore that voice, but we could not deny that we had heard its message.

Planning in Cleveland after Krumholz

After serving three years for Democratic Mayor Carl Stokes and six years for conservative Republican Mayor Ralph Perk, Norm Krumholz left the City Planning office in 1979 during the second and final year of the tumultuous term of populist Mayor Dennis Kucinich, a time that was marked by open warfare between the mayor’s office and the corporate community. Krumholz then began his second Cleveland career, as a professor of urban planning at Cleveland State University, where he continues to teach today and to influence new generations of city planners.

What, then, was the fate of equity planning in Cleveland city government after Krumholz’ departure? Although it is fair to say that the term “equity planning” quickly disappeared from the vocabulary of the Cleveland City Planning Commission, it is also a fact that the “top-down,” developer-driven style of city planning in Cleveland was permanently replaced by a planning process that incorporated grass-roots citizen engagement and close partnerships with neighborhood-based organizations.

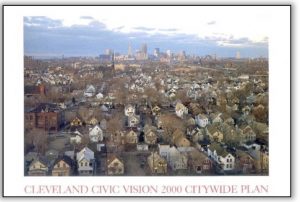

Hunter Morrison was appointed as City Planning Director in 1981 by Mayor George Voinovich, who was elected with a mandate to restore prosperity to Cleveland by establishing “public-private partnerships” between the city and its business community. Morrison’s appointment coincided with the first signs of a renewed interest on the part of developers in rebuilding Cleveland. As these developers looked to the City Planning office for guidance, it was evident that Cleveland needed to prepare a comprehensive plan that re-focused attention on the more traditional tools of land use plans, development policies, infrastructure plans and urban design standards. Morrison did just that.

With support from the local philanthropic and corporate communities, Morrison led his staff in preparing the Civic Vision 2000 Citywide Plan (managed by Robert Brown) and the Civic Vision 2000 Downtown Plan (managed by Robert Bann). These documents proposed detailed land use plans to guide the location of development, policies to guide the nature of development and revitalization, and capital improvement plans to guide investments in roadways and transit. Not unlike the Krumholz-era plan, the Citywide Plan’s lead goal was to “create neighborhood conditions that meet the needs and aspirations of residents of all incomes and ages.”

The plans – prepared with the most extensive citizen engagement process in the city’s history – were implemented through such projects as North Coast Harbor (with the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Great Lakes Science Center), Gateway (with the stadium and arena projects), the Euclid Corridor transit line, industrial parks, shopping centers, and thousands of new houses in Cleveland’s neighborhoods. Morrison also placed new priority on urban design, demanding that developers demonstrate respect for the city by producing first-class architecture that would enhance the city’s visual image.

Morrison held the positon of City Planning Director for the next 21 years, longer than anyone else in the department’s history. He served through the mayoral terms of George Voinovich and Michael White, and then stepped down as City Planning Director when his then-wife, Jane Campbell, ran for mayor and won in 2001.

Chris Ronayne was appointed City Planning Director in 2002 by Mayor Campbell. He served in that capacity for three years, after which time he became the Mayor’s Chief of Staff during the final year of her term. While continuing the direction set by Morrison, Ronayne focused his attention on the city’s lakefront. He mustered significant political and philanthropic support for production of the Connecting Cleveland Waterfront District Plan (managed by Debbie Berry). This plan sought to “re-connect” Cleveland to its lakefront and its riverfront, undoing the obstructions that had been created by placement of freeways, freight rail lines and private development along these waterfronts. A key element of the plan was the transformation of the West Shoreway into a lakefront parkway.

Robert Brown moved up from Assistant Director to Director of the Cleveland City Planning Commission during the last year of Mayor Campbell’s four-year term and was re-appointed as Director in 2006 by newly elected Mayor Frank Jackson. Brown, who started in the City Planning office in 1985 as project manager for the neighborhood portion of the Civic Vision 2000 Plan, served as Director until he retired from the City in mid-2014.

While continuing the direction set by his two predecessors, Brown focused his attention on strengthening the city’s neighborhoods through design review, preparation of neighborhood-based plans, “placemaking” and contemporary zoning regulations – from urban agriculture to pedestrian-oriented development to “live-work” space. Brown spoke nationally on strategies for “Reimagining & Reshaping Cleveland” as a smaller but more vibrant and more prosperous community, building on the city’s historic assets. Brown also managed the City’s engagement in transportation planning for the West Shoreway, Innerbelt and Opportunity Corridor projects.

In 2007 the City Planning office completed work on its next comprehensive plan, the Connecting Cleveland 2020 Citywide Plan (managed by Fred Collier). That plan attempted to blend the development orientation of the Civic Vision Plan with the equity orientation of Policy Planning Report, while continuing the commitment to citizen engagement and partnerships with neighborhood-based organizations.

Fred Collier took the helm of the City Planning office in mid-2014, moving up from his position as Assistant Director and his prior role as project manager of the Connecting Cleveland 2020 Citywide Plan. Collier charted a new course for the City Planning office, with a focus on improving the health of Clevelanders through use of “health impact assessments” to gauge the impacts of proposed development projects and programs on the health of city residents, particularly those residents living in economically challenged neighborhoods. Collier brought the city to the forefront of regional and national discussions regarding the “social determinants of health” and the associated “Place Matters” movement.

Collier, Cleveland’s first African-American City Planning Director, intensified the department’s focus on issues of social and economic equity, consistent with Mayor Frank Jackson’s attention to improving conditions for those he called “the least among us” and, notably, consistent with Norm Krumholz’ focus on creating a wider range of choices for those Clevelanders who have few, if any, choices.

*****************************

article written by:

Robert N. Brown, FAICP

February 2015