Annexation and Mayor Sensenbrenner

The Story of How Columbus Grew to be the Largest City in Ohio

By Alexander Tebbens

Since its founding over two hundred years ago, the success of the City of Columbus has never been a given. Due to its lacking entirely navigable rivers and many natural resources that drive a city’s growth, Columbus has been overshadowed by Ohio’s other large cities, Cleveland and Cincinnati, for much of its history. During the latter half of the twentieth century, however, Columbus experienced an era of unprecedented growth. Since 1954, Columbus has grown to become Ohio’s largest city both in land area and population. The growth has allowed Columbus enough economic stability to have remained relatively untroubled by the recent recession as compared to other Ohio cities1. Columbus’ success is linked to its growth, which is itself linked to the policies of Maynard (Jack) E. Sensenbrenner, Columbus’ mayor from 1954 to 1960 and from 1964 to 1972.

In the years following World War II, there was a general exodus across the country from cities to the suburbs. Residents leaving for the suburbs took a toll on their former cities. Property and income tax bases declined steeply and businesses failed as people preferred to shop close to their new homes instead of venturing downtown. Growing suburbs also began to encircle cities, which cut them off from further growth. By the 1950s, the migration to the suburbs was already underway in Ohio’s cities2. In 1954 Columbus elected a new mayor whose leadership team knew that Columbus did not have to end up strangled by its suburbs. Mayor Sensenbrenner made it the central goal of his administration to keep his city healthy and safe from its suburbs.

Columbus City Council and Mayor Sensenbrenner’s solution to the problem of suburban growth was simple and led to policies that would cause Sensenbrenner to “put a greater stamp on Central Ohio than any [other] human being,” according to City Auditor Hugh Dorrian. The solution was simply that Columbus would outgrow its suburbs. There was a large amount of unincorporated land surrounding the city and this was where people were moving. If the City of Columbus could annex this land, then it, and not the suburbs, would be the beneficiary of those residents. Adding new land would not only add new residents to the city, but it would also expand the city’s tax base and provide new commercial and industrial centers. State laws in Ohio made annexation difficult, however Mayor Sensenbrenner and the Columbus City Council knew that they had a powerful tool at their disposal. In Central Ohio most smaller towns and townships could not afford to create and maintain their own water and sewer infrastructure. For a fee, in fact, it was Columbus that was providing water and sewer services and infrastructure to its own suburbs and adjacent townships 5. By controlling access to water and sewer systems, the City of Columbus could control growth in Central Ohio.

In March and April, 1954 the Columbus City Council passed two sweeping resolutions that would form the base for its many years of growth and transformation. On March 8th, 1954, the Columbus City Council passed, and Mayor Sensenbrenner approved, a resolution that stated “To preserve the city’s water supply for the benefit of residents of Columbus…no further extensions of existing water mains of no additional taps be made except in territories annexed to Columbus” because “ an emergency exists in the usual daily operation of the Department of Public Service, Division of Water, in that it is immediately necessary to make provisions for the conservation of the water supply for the inhabitants of the City of Columbus”6. The following month on April 5th 1954 the Columbus City council passed and Mayor Sensenbrenner approved a second resolution that would also have a profound effect on the growth of the city. The April 5 resolution declared that “ To protect the health of the residents of Columbus…no further extensions of existing sewer mains, trunks, and laterals, or no additional taps be made in territories outside the corporate limits of the City of Columbus, except in territories annexed to Columbus”7.

On the surface, the resolutions of March and April 1954 make it seem that Mayor Sensenbrenner and the Columbus City Council were merely concerned about the wellbeing of the residents of Columbus. The texts of the resolutions seem to explicitly state that their purposes were to ensure that residents of the city have sufficient water during a so-called “emergency” water shortage and to prevent the spread of disease by creating fewer sewer lines. A closer look at the texts reveals that this interpretation is not entirely correct. The resolutions clearly state that the city cannot keep extending water lines to suburbs because of the water shortage, and more sewer lines because of health concerns. Both resolutions also clearly state that the only exception to their prohibition on new water and sewer lines would be for areas that are annexed by the city. In circumstances of annexation, the city was “required by law” to provide the new territories with water and sewer lines 8,9. If there truly were a shortage of water for the city, then adding lines anywhere should exacerbate the shortage regardless of whether or not the land was annexed. Also, if concerns about public health were keeping the city from extending sewer lines, it is unclear as to how extending lines to newly annexed areas would be any less of a public health hazard than to non-annexed areas. On the day following the April 5th resolution, the Columbus Citizen Journal noted the true reason for the resolutions that “ the legislation had been advocated to encourage annexation of outlying areas”10.

Not only did the resolutions of March and April 1954 overstate how dire the water and sewer situation was in Columbus, they also left out an important detail about how the city interacted with its suburbs. In theory, following the resolutions would result in no further water or sewer lines except in areas annexed to Columbus. In practice, however, Columbus’ water and sewer policy was much more complicated than the resolutions implied. In fact, the city had designated service areas in which they would provide water and sewer services to its suburbs. These service areas allowed for space for the suburbs to grow but ensured that there were gaps between them so that Columbus would always have avenues for its own growth11. Providing services to the suburbs was a large source of revenue for Columbus as it charged premiums for water and sewer services outside of its boundaries. The revenue collected from the premiums actually helped fuel Columbus’ annexation campaigns. Funds collected from providing services to the suburbs were used to build and expand the infrastructure in areas that were annexed into Columbus12.

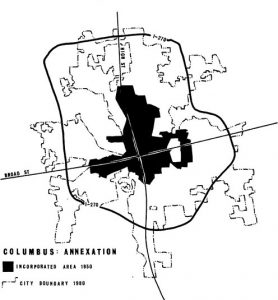

The year 1954 would be the trial run for the annexation campaign. The City of Columbus’ annual report on 1954 states that the city was forty square miles in 1950 and in 1954 it grew by 2.768 square miles- the largest amount of annexed property since 192913. The annual report of 1954 also describes the Columbus’ Master Plan towards annexation and reveals the strategies employed by the City Council and Mayor Sensenbrenner. At first the city proposed a one-shot solution to completely solve its problem of the suburbs. The city first tried annexation referendums on entire surrounding townships. The referendums failed and the city was forced to adjust its strategy. The city’s new strategy would be to try to entice smaller areas to petition for annexation. The City of Columbus actively campaigned to make annexation seem more desirable including the creation of annexation checklists that described annexations advantages to residents14.

Throughout the mid and late 1950s, the City of Columbus grew at an unprecedented rate. In 1955 the city added 9.8 square miles, which was the largest addition to the city ever15. Also in 1955, The Ohio General Assembly made for many the annexation decision a little easier. The law was changed so that people were no longer required to switch school districts if their hometown or city changed. This allowed residents in areas annexed by the city to gain the benefits of being part of the city but let them keep their old school district16. The new law gave a new reason to pursue annexation, getting the benefits of living in Columbus, while not having to deal with city schools. The next year the city added 12.26 square miles and surpassed of the previous year’s record17. By the end of 1957 Columbus had more than doubled its 1950 size. It was noted in the city’s annual report for 1957 that annexation was growing in popularity as residents in the surrounding townships voiced their desire for access to city services such as efficient fire and police departments18. In 1959 Sensenbrenner lost his bid for mayoral reelection. In Sensenbrenner’s absence annexation slowed and fewer than six square miles were added in the next four years19, 20, 21, 22. The rate of annexation took off again when Sensenbrenner once again took up the office of Mayor in 1964, that year 8.25 square miles were added23. By the end of 1971, and Sensenbrenner’s last year as mayor, the City of Columbus had grown to 168.79 square miles. Leaving office in 1972 Sensenbrenner left behind a city that was more than four times larger than the one he took charge of in 195424.

Through annexation, Columbus gained not only land, but also additional population, new commercial centers, and it achieved Sensenbrenner’s initial goal of escaping strangulation by its suburbs25. Under Mayor Sensenbrenner the city also finally outgrew Cincinnati and Cleveland in size, to become the city with the largest area in Ohio. The City of Columbus now takes up nearly all of Franklin County and stretches into Delaware, Union, and Licking counties. In many cases, the city has engulfed its own suburbs26. Suburbs that Mayor Sensenbrenner was concerned about cutting off Columbus, such as Upper Arlington, Bexely, Grandview, Worthington, and Westerville now are all completely or nearly completely surrounded by Columbus27.

On the surface, Sensenbrenner’s policy of aggressive annexation appears to have been an overwhelming success. Columbus is now over 225 square miles, and has prevented itself from being engulfed by its suburbs 28. Discussion of the history of Columbus’ annexation policy often focuses on its successes, how it grew to an unprecedented size, thrived economically and beat back the approaching suburbs. Hidden within the successes, however, are some very unflattering facts about the city’s growth. Between 1950 and 2000 the city added around 357,000 residents. For the past decade, the main population growth in Columbus has been on the northern and eastern boundaries, particularly near new shopping areas such as Polaris Fashion Mall and Easton Town Center29. The city’s largest shopping areas are no longer at its middle but at its peripheries30. In the areas that made up the city in 1956, there was actually a loss of around one hundred thousand individuals31. Areas that were once in or near the core of the city, such as Franklinton, the Hilltop, the Near East Side and Linden, have all experienced drops in population32. Perhaps Columbus is no longer in danger of being strangled by the suburbs but it had been in the process of strangling itself. Until recently, with each push outward the city has increasingly become a shell around an empty center. During the periods of annexation, the City of Columbus chased development on its edges and often neglected its center. In recent years, however, the city has been aggressively pushing for revitalization in its core areas. These revitalization pushes have begun to yield two bright spots of growth in the city’s center. Between the years 2000 and 2010, Downtown and the area named the Short North, have gained between 500 and 2500 residents33. Since the 1980s, the Short North neighborhood has evolved into the city’s thriving arts district34. In 2010, the City of Columbus enacted a strategic plan to cultivate its downtown. The plan involves creation of more housing, parks and attractions, and new business in the heart of the city35. After years of neglect, the center of the City of Columbus is starting the process of filling itself in again.

For nearly fifty years Mayor Sensenbrenner’s annexation policy was the standard operating procedure for Columbus and for the most part it has worked. In 2003, however, Mayor Michael Coleman introduced a change in the policy with a plan dubbed “Pay as you Grow”. Under the new policy developers and residents of new annexations have to bear some of the infrastructure costs associated with adding that land to the city36. Mayor Coleman explained that aggressive annexation is no longer needed, as the danger of the city being encased by the suburbs has passed. Mayor Coleman argued that the city’s prior annexation policy put a strain on city taxpayers, as it was ultimately they who had to pay for the additional water and sewer lines and other infrastructure added to annexations37. In recent years the rate of annexation has slowed, and some suburbs are now adding land at a faster pace than Columbus38. Mayor Sensenbrenner’s annexation policy may have propelled the City of Columbus past its suburbs from the 1950s, but there are new dangers encountered by the city. Columbus’ fifty years of growth has brought it into contact with a new set of suburbs. Towns such New Albany and the area of Orange Township are so far from downtown that they would never have been considered a threat by Sensenbrenner, yet are growing both in land and population at an accelerated pace 39, 40. Only time will tell if Columbus will be able to out-maneuver this new set of suburbs.

References:

1.) Hallett, J., Johnson, A., Niquette, M. (2007, December 9) Columbus- The Bright Spot Among Ohio’s Biggest Cities isn’t Immune to Problems and isn’t Keeping up with its Peers Nationwide. The Columbus Dispatch, pp. 01A

2.) City of Columbus (1957) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

3.) Ferenchick, M. (2009, June 8) Harrison W. Smith Jr. Hones Legacy on City’s Growth The Columbus Dispatch.

4.) Howlett, J., Johnson, A., Niquette. M., (2007)

5.) Ibid.

6.) City of Columbus (1954) City Council Resolution, March 8.

7.) City of Columbus (1954) City Council Resolution, April 5.

8.) City of Columbus (1954) City Council Resolution, March 8.

9.) City of Columbus (1954) City Council Resolution, April 5.

10.) (1954, April 6) Out-of-City Water, Sewer Rates to Rise. Columbus Citizen Journal.

11.) Mid Ohio Regional Planning Commission (1977) A Checklist for Evaluating Annexation

12.) Arthur D. Little Inc, Consultants to Department of Development, City of Columbus (1970) Annexation Issues and Recommendations- The Columbus Plan 1970-1960, Implementation Study No. 6

13.) City of Columbus (1954) Annual Report Department of Public Services

14.) Ibid.

15.) City of Columbus (1955) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

16.) South Western City Schools (2010) The Win-Win Agreement Retreived at: http://www.swcs.us/Home/BoardOfEducation/News/Win-Win%20Information_2010.pdf

17.) City of Columbus (1956) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

18.) City of Columbus (1957) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

19.) City of Columbus (1960) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

20.) City of Columbus (1961) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

21.) City of Columbus (1962) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

22.) City of Columbus (1963) Annual ReportDepartment of Public Services.

23.) City of Columbus (1964 ) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

24.) City of Columbus (1971) Annual Report Department of Public Services.

25.) Howlett, J., Johnson, A., Niquette. M., (2007)

26.) Gebolys, D. (2008, February 4) Stunted Growth- Columbus Still Has an Appetite for Annexation, but it’s Swallowing up Land Much Slower Lately. The Columbus Dispatch. Pp. 01B

27.) Ferenchick, M. (2003, November 22) Builders have Questions about Mayor’s Growth Ideas- Developers, Residents Would Help Pay Cost on the City’s Edge. The Columbus Dispatch. Pp. 05C

28.) Bush, B. (2011, March 11) Census Shows Columbus’ Growth was Uneven. The Columbus Dispatch Retrieved at: http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2011/03/11/census-shows-columbus-growth-was-uneven.html

29.) Howlett, J., Johnson, A., Niquette. M., (2007)

30.) Bush, B. (2011)

31.) Howlett, J., Johnson, A., Niquette. M., (2007)

32.) Bush, B. (2011)

33.) City of Columbus (2010) Department of Development Planning Division. City of Columbus 2000-2010 Change for Total Population.

34.) Duffy, J. (2012, August 7) In Columbus, Ohio, an Arts Belt is Thriving New York Times. Retrieved at:

35.) City of Columbus (2010) 2010 Downtown Strategic Plan Executive Summary. Retrieved at: http://development.columbus.gov/uploadedFiles/Development/Planning_Division/Document_Library/Plans_and_Overlays_Imported_Content/2010%20DCSP%20Exec%20Summary%20+%20Introduction.pdf

36.) Ferenchik, M. (2003)

37.) Ibid.

38.) Gebolys, D (2008)

39.) Lyttle, E. (2013, September 3) New Albany Growth Marches on Toward Licking County. The Columbus Dispatch Retrieved at: http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2013/09/03/new-albany-growth-continues-its-march.html

40.) Orange Township (2010) Land Use Plan Chapter 2: Demographic Trends Retrieved at: http://orangetwp.org/DocumentCenter/View/74