BISHOP URGES CATHOLICS IN SUBURBS TO REACH OUT TO THOSE LEFT IN CITY

Plain Dealer, The (Cleveland, OH) – April 16, 1996

Ann Racco and her family are like hundreds of thousands in northeast Ohio who left the central cities during the last four decades for the suburbs.

But Racco is different from most. She is trying to build a link with the people and the communities she left behind.

“I really thought Christians should not be separated by mere logistics, by a few miles or the fact that you live in a mostly white community,” said Racco, a Medina County mother of two.

From her 7-acre slice of Sharon Township, Racco is acting on a Cleveland Catholic Diocese initiative by bridging the eco- HOnomic, social, and geographic distance of her affluent community to the central city neighborhoods of Cleveland.

Yesterday, Cleveland Bishop Anthony M. Pilla and other diocese officials held a news conference to present an action plan on how Catholics can respond to the bishop’s call to “build new cities where children will be able to live in decent homes, have sufficient food, and be properly educated for meaningful employment.”

Pilla’s Church in the City program emphasizes that the fate of central cities affects suburbs, and that suburbanites must be concerned about how their urban counterparts fare.

Through her church, Holy Martyrs in Medina Township, Racco and other Catholics are building a link to San Juan Bautista parish on Cleveland’s near West Side. Last year, they held a joint Mass, a meal, and other functions. In March, the parishes held a joint art show for their children.

Those contacts, though only a beginning, have helped transform how Racco and other suburbanites view their lives as Catholics.

“It has really changed my reading of the gospel,” said Racco, 39. “I can’t read the gospel in any other light than the preferential option of the poor” – that is, that God is especially open to the cries of the poor.

The transformation of Racco and others has come about as the Cleveland diocese tries to translate its Church in the City initiative into a program that Catholics can act on.

But even as the process touches its participants in a positive way, church officials are finding resistance from some who do not yet understand the message that the suburbs and the city share the same fate. “We have a long way to go,” said Pilla.

More than two years ago, Pilla first proposed a role for the Catholic Church in helping revitalize central-city neighorhoods, the former homes of hundreds of thousands of Catholics who moved to the suburbs along with much of the middle class.

To turn the proposal into an action plan, the diocese held a yearlong series of discussions with several thousand of the more than 800,000 Catholics in the eight-county diocese. The intitiative has drawn national attention and is being looked to by other dioceses as a possible model to follow, said Pilla, who is president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops.

The plan calls for the diocese to build affordable housing, promote education for inner-city youths, help provide job training to the disadvantaged, and create other programs that revitalize inner-city neighborhoods.

The diocese also will provide $150,000 in grants to promote the kind of partnerships Racco’s church has developed with San Juan Bautista. One of the main goals, the diocese says, is to break down the barriers between communities that are created when people of different classes and races live far apart.

A major goal of the action plan is to achieve the kind of conversion in others that Racco went through last year. While it has many successes it can point to, the diocese admits the process will be a slow and sometimes painful one for the Catholic community.

The difficulty comes in convincing suburban Catholics that they have an economic and moral imperative to help revitalize the central cities.

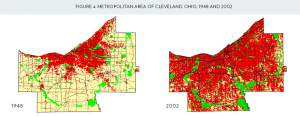

The disappearance of the middle class from the central cities to the suburbs since the 1940s and ’50s has weakened inner-city neighborhoods, leaving them with high percentages of poor people who lack the financial resources and the political clout to protect their communities from decay.

To create communities in what was farmland, the suburbs spend more tax money on sewers, roads and buildings, while the same infrastructure in the central city goes to ruin. The economic cost is coupled with an environmental one as well, as the new communities threaten farms and forests.

As the city and suburbs drift apart economically and socially, the affluent communities do not view the inner-city problems as ones they should care about and help solve, the bishop said.

“We had never intended to put guilt on anyone, but what has been perceived by some is that we are blaming them for moving to a suburb, blaming them for trying to improve their family situation,” said Pilla in an interview last week. “We weren’t saying that, but we had to deal with that. We are not done yet.”

To that end, the diocese has created various agencies to educate its members and the general public about how urban sprawl can harm people and neighborhoods, both in the city and in the country. In the next two years, the diocese will initiate a Social Action Leadership Institute to promote the church’s social mission, and it will create a land-use task force to bring more of the urban land issues to the forefront.

That conversion will be a slow one, say others involved in urban sprawl issues.

“What we are asking people to do is to change the way they think about making decisions,” said Kevin Snape, assistant director and project manager of the Regional Environmental Priorities Project, which last year identified urban sprawl as northeast Ohio’s greatest environmental threat. “We are in a mindset, and the hardest job is to get people to look at something in a very different way.”

Pilla said the church could use moral persuasion, linking the initiative to religious teachings, but ultimately the change, for individuals, would have to come from within.

“We’re running counter-culture on a lot of things,” Pilla said. “We are talking about being one people. We are talking about the common good. We are talking about mutual responsibility for each other in a culture that promotes privatism when it comes to religious matters and really exults in the individual. I think we’re really struggling with that.”

Pilla draws hope for the initiative from the response of parishioners like Racco.

For her, the conversion was almost instantaneous. Hearing Pilla speak on Church in the City last year, Racco said she realized that being a Catholic meant reaching out to help others, including other Catholics, in a meaningful way.

She knows the understanding will come more slowly for others in the suburbs.

“I don’t think it is going to be easy, but I see some hopeful signs,” she said. “This is a movement that was not happening in my parish a year ago, and it is being resoundingly supported now.”