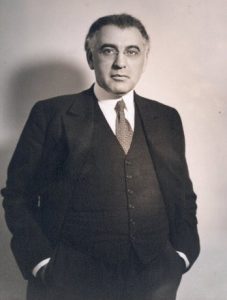

Abba Hillel Silver (1893-1963)

Abba Hillel Silver by Rafael Medoff

“Silver, Abba Hillel (28 Jan. 1893-28 Nov. 1963), rabbi and Zionist leader, was born Abraham Silver in the Lithuanian village of Neustadt-Schirwindt, the son of Rabbi Moses Silver, a proprietor of a soap business, and Dina Seaman. The family immigrated to the United States in stages, settling on New York City’s Lower East Side in 1902, when Silver was nine years old. He attended public school in the mornings and Jewish religious seminaries in the afternoons yet still made time for his growing interest in the fledgling Zionist movement. He and his brother Maxwell founded the Dr. Herzl Zion Club, one of the first Zionist youth groups in America, in 1904. On Friday evenings, Silver attended the mesmerizing lectures of Zvi Hirsch Masliansky, the most influential Zionist preacher of that era. “I can still taste the sweet honey of his words,” Silver remarked many years later. Inspired by Masliansky, Silver soon developed a reputation of his own as an orator, equally eloquent in Yiddish, Hebrew, and English. He addressed the national Federation of American Zionists convention when he was just fourteen.

During his high school years, Silver excelled in secular studies and increasingly moved away from his Orthodox religious upbringing. Upon graduation, in 1911, he enrolled at the University of Cincinnati and the Hebrew Union College, the rabbinical seminary of Reform Judaism. He was not fazed by the Reform movement’s anti-Zionism; indeed, it may have whetted his appetite. He organized Zionist activity on campus, edited student publications, won prizes in public speaking contests, and graduated in 1915 as valedictorian of his class.

At his first pulpit, in Wheeling, West Virginia, Silver soon earned a local and regional reputation as an orator. He also earned the enmity of more than a few Wheeling residents by his involvement in controversial causes, especially his sponsorship of a lecture in 1917 by Senator Robert M. La Follette, who opposed U.S. entry into World War I. That summer, Silver was lured away from Wheeling to Cleveland, Ohio, to become the spiritual leader of the Temple (Tifereth Israel), one of the country’s most prominent Reform congregations. In Cleveland he continued to attract public attention, usually as an outspoken defender of labor unions, and frequently sparred with groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution, which denounced him as a dangerous radical.

Still, it was the cause of Zionism that was closest to Silver’s heart, reinvigorated by a visit to British-administered Palestine in the summer of 1919. Soon he was speaking throughout the United States on behalf of the Zionist movement, attracting large audiences and rave reviews. “Many who heard him last night pronounced him as one of the greatest orators the

Jews possess,” a newspaper in Texas declared after one of Silver’s addresses. In 1923 he married Virginia Horkheimer; they had two sons. While two assistant rabbis handled the bulk of the Temple’s routine rabbinical duties, Silver rose to prominence on the national Jewish scene. As leader of Cleveland’s Zionists – who comprised one of the largest districts of the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) – he spearheaded protests against British restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine and organized boycotts of products from Nazi Germany.

The escalating Nazi persecution of Jews, the apathetic response of the Roosevelt administration to news of Hitler’s atrocities, and England’s refusal to open Palestine to refugees from Hitler, stimulated a mood of growing militancy in the American Jewish community during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Silver both symbolized American Jewish militancy and helped encourage its spread. In August 1943, he was appointed co-chair of the American Zionist Emergency Council (AZEC), a coalition of the leading U.S. Zionist groups, alongside Rabbi Stephen Wise. Until then Wise had been widely regarded as the most powerful leader of the American Jewish community. Silver’s elevation to the co-chairmanship of AZEC launched a bitter political and personal rivalry between the two men that would endure for years.

While Wise, a loyal Democrat, was reluctant to criticize the Roosevelt administration’s hands-off attitude toward Palestine and European Jewry, Silver did not hesitate to speak his mind. Silver’s followers characterized the contrast between the two as “Aggressive Zionism” versus “the Politics of the Green Light [from the White House].” Within weeks of assuming the AZEC co-chairmanship, Silver spoiled Wise’s plan to downplay the Palestine issue at that year’s American Jewish Conference. Wise had hoped to mollify Washington and London, as well as Jewish critics of Zionism, by skirting the Jewish statehood issue, but Silver electrified the delegates with an unannounced address in which he vigorously demanded Jewish national independence. The “thunderous applause” that greeted his speech said as much about Silver’s new prominence as it did about the American Jewish mood.

Under Silver’s leadership, American Zionism assumed a vocal new role in Washington, D.C. Mobilized by AZEC, grassroots Zionists deluged Capitol Hill with calls and letters in early 1943 and late 1944, urging the passage of a congressional resolution declaring U.S. support for creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine. The opposition of the War and State Departments stalled the resolution in committee but did not deter Silver from campaigning in the summer of 1944 for the inclusion of pro-Zionist planks in the election platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties

that summer. Silver’s ability to maneuver the two parties into competition for Jewish electoral support was a testimony to his political sophistication even if, much to Wise’s chagrin, the Republican platform went beyond what AZEC requested by denouncing FDR for not challenging England’s pro-Arab tilt in Palestine.

While successfully usurping Wise’s leadership role in the Jewish community, Silver took care to guard his own right flank. He quietly hired several militant Revisionist Zionists to help shape AZEC policy and guide its public information campaigns. He also engineered a public reconciliation between the Revisionists’ U.S. wing and the mainstream Zionist movement.

During the postwar period, Silver and AZEC stepped up their pressure on the Truman administration with a fresh barrage of protest rallies, newspaper advertisements, and educational campaigns. Silver’s effort in early 1946 to link postwar U.S. loans to British policy in Palestine collapsed when Wise broke ranks to lobby against linkage. More successful were Silver’s behind-the-scenes efforts to mobilize non-Jewish Americans on behalf of the Zionist cause. AZEC sponsored the American Christian Palestine Committee, which activated grassroots Christian Zionists nationwide, and the Christian Council on Palestine, which spoke for nearly 3,000 pro-Zionist Christian clergymen.

Although the Truman administration wavered in its support for the 1947 United Nations plan to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, a torrent of protest activity spearheaded by Silver and AZEC helped convince the president to recognize the new State of Israel just minutes after its creation. Silver’s protests against the U.S. arms embargo on the Middle East, however, were consistently rebuffed by the administration.

In the aftermath of Israel’s birth, Silver pressed for a clear separation between the new state and the Zionist movement, insisting that Israel should not control the World Zionist Organization or other Diaspora agencies. The leaders of the ruling Israeli Labor party had always viewed Silver with some suspicion because he preferred the free market advocates of the General Zionist party to the socialists of Labor. His effort to break Israeli hegemony over the Diaspora enraged Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. The Labor leadership threw its support behind a faction of disgruntled ZOA members who resented Silver’s prominence, and together they forced Silver and his followers from power in 1949.

Silver resumed full-time rabbinical duties at the Temple, with only an occasional and brief foray into the political arena when he could utilize his Republican contacts to lobby on Israel’s behalf. He turned his attention to

religious scholarship, reading voraciously and authoring several well- received books on Judaism. He died suddenly at a family Thanksgiving celebration in Cleveland.

Silver’s reign marked a political coming of age for American Jewry. His lobbying victories infused the Jewish community with confidence and a sense that their agenda was a legitimate part of American political culture– no mean feat for a community comprised largely of immigrants and children of immigrants. The Silver years left their mark on the American political scene as well. After the inclusion of Palestine in the 1944 party platforms, Zionist concerns assumed a permanent place in American electoral politics. Additionally, the swift U.S. recognition of Israel in 1948, a decision made, in large measure, with an eye toward American Jewish opinion, was a first major step in cementing the America-Israel friendship that has endured ever since.”

Rafael Medoff

“Abba Hillel Silver” From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Abba Hillel Silver: A Personal Memoir by Rabbi Leon I Feuer

The Jewish State in Abba Hillel Silver’s Overall World View by Zohar Segev

The American Herzl? from the Jerusalem Post 11/30/2010

Abba Hillel Silver’s Rise to Zionist Leadership by Dr. Rafael Medoff

Abba Hillel Silver Obituary (NY Times 11/29/1963 from Cleveland Jewish History.net)

Abba Hillel Silver website by Dr. Arnold Berger