“Tremont: A Product of Its Past, a Piece of Its Future” by Tara Vanta from Belt Magazine

Category: Tremont

The Paradox of Progress in Tremont, Ohio By Dawn Ellis

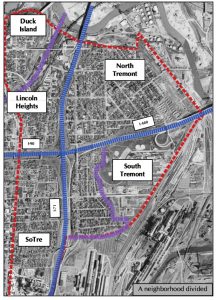

map courtesy Tremont West Dev.

The Paradox of Progress in Tremont, Ohio

By Dawn Ellis

What does progress look like and how is it measured? What is gained and what is lost in the name of progress? For the city of Tremont, Ohio, for decades, progress was defined through the destruction of neighborhoods, social capital and community cohesion. Long-term Cuyahoga County Engineer Albert Porter envisioned progress in terms of rapid, individual automobile transport from the Central Business District to the suburbs. During his almost 30-year tenure (1947 to 1976) he would oppose a city subway plan and endorse and establish most of the current highway system linking Cleveland to the suburbs. To encourage the supposed good of increased access to the Central Business District of Cleveland from the outlying suburbs through the construction of highways, Tremont was eventually carved into 4 quadrants that now attempt to relate to each other as the whole they once represented.

If Tremont will be successful in recapturing the sense of cohesion it previously had remains to be seen, but the question that lingers is: how do we as citizens determine the best use of our land, and how do we value the intangibles such as social capital and collective memory against financial and economic gain?

The Tremont area, 3.3 square miles bounded roughly by the Cuyahoga River to the east and north, West 25th Street to the west and the Harvard Denison Viaduct and Riverside Cemetery to the south, was settled in 1818 by Seth Branch and Martin Kellogg, from New England. It began as more of a colony within the city of Ohio City but would eventually merge with Cleveland in 1854. The area grew slowly. The Reverend Asa Mahan (then president of Oberlin) envisioned Tremont’s acres as a cultural center not only for Cleveland, but all of Ohio. Reverend Mahan, with landowners Seth Branch, Martin Kellogg, H.R. Hadlow, Hiram Aikens and Brewster Pelton, moved forward with a plan to establish a university in the area.

“University Heights” as an idea in 1850 would be laid out with neighborhoods and streets plotted, inspired by the vision of bucolic serenity and high culture. University, Professor and College were some of the first plotted street (these streets still exist in Tremont), names chosen to reflect the educational and cultural aspirations of the settlement. The university idea would eventually fail but University Heights became an exclusive residential area with impressive historic architecture whose Franklin Avenue rivaled the famous Euclid Avenue on Cleveland’s east side.

The War of 1812 had helped establish Cleveland as a trade center and by the 1820s the port was a successful commercial hub. In 1832 the Ohio and Erie Canal, of which Cleveland served as the terminus, was completed and some of the commercial promise of the lake was realized. By 1849 with the completion of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland’s prosperity and growth were intimately tied to transportation, first through the canal, then through the railroads, and finally through the automobile industry.

The Civil War period proved immensely transformative for Cleveland. By 1860 there were five railroad lines that ran in and out of the city; it was well positioned to profit from the trade in raw materials and other goods. At the turn of the century Cleveland’s important industries of iron, steel and oil refining played a part in the city’s entry into the emerging automobile industry. Its combination of access to raw materials, a burgeoning manufacturing base and a solid class of well-to-do consumers helped make Cleveland a leading automobile city in the United States. Spurred by the work of such people as Alexander Winton, who introduced his first car to Cleveland in 1896, the automotive and automotive parts industry played a large role in the commercial development of Cleveland. Automakers such as Winton, Peerless and Baker Electric helped solidify the importance of the automobile in northeast Ohio and Cleveland.

Over the years Tremont’s upper scale residential atmosphere gave way to the development of such industries as steel making and oil refining that led to an influx of immigrant workers to the area and an exodus of the New England families that had settled the land, who continued to move south and west, towards suburbs like Parma. One of the earliest industrial establishments, the Lamsom-Sessions Company, a bolt manufacturer in 1869, helped lure a diverse population to this part of Cleveland. Towards the second half of the 1800s, parcels in Tremont were among the most affordable in the area and working class families were able to purchase homes, or land on which to build homes, that were near their places of employment; visions and plans of grand estates and gardens gave way to working class residential and industrial neighborhoods.

New immigrants could establish veritable ethnic enclaves within Tremont; families could live, work, worship and shop among fellow immigrants. Among the first of these immigrant groups to settle in Tremont were the Germans and Irish, who concentrated themselves in the lowlands. German and Irish were followed by Polish, Greek, Ukrainians and Puerto Ricans-more than thirty nationality groups have lived in Tremont over the years. The legacy of these different groups can still be found in the architecture of the housing that reflects a variety of styles such as Victorian and Queen Anne.

Unfortunately the ethnic and class cohesion that Tremont experienced did not protect it from the suburban drain that began to empty the urban areas across the country by the 1930s. Despite the grandeur of Franklin Avenue and its impressive churches, Tremont was not an overall affluent section of Cleveland. The conditions of working class industrial regions were sometimes poor and the economic devastation of the Depression hit working class communities like Tremont especially hard. Some homes had no running water well into the 1950s, and houses built for single family occupancy served twice as many people as intended.

Congestion and poverty were rampant, and by 1939-40 Tremont was slated for governmental intervention in the form of a public housing development known as Valley View Homes. This is the map of the location of the development.

This project was seen at the time as a public service and residents were generally receptive to this sort of governmental program. The plight of the 250 families that were displaced as a result of this project foreshadowed what would transpire repeatedly in Tremont.

As property values fell and population numbers decreased throughout the 1950s, Tremont become a prime candidate for the urban renewal projects (often designed to facilitate the flow of vehicular traffic in and out of the Central Business Districts of cities) that spread over the nation that combined the construction of highways and housing developments with mass razing and resident relocation in an effort to combat slums and urban blight. Financially able residents had been leaving the area for southern suburbs since the late 1800s, yet at that time, more people were entering than leaving Tremont and the population continued to rise until its peak of 36,686 residents in 1920.

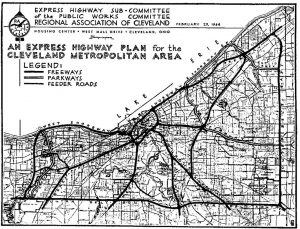

Cleveland’s Freeway Plan of 1944 (that followed an earlier plan proposed in 1940) was designed as a multimillion dollar integrated freeway system to relieve downtown congestion.

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland’s overall urban renewal plan was the largest in the United States and targeted more than 6,000 acres east of the Cuyahoga River in the inner city. By 1966 the Department of Housing and Urban Development had authorized assistance for seven urban renewal projects in Cleveland: Longwood, St. Vincent’s Center, Garden Valley, East Woodland, Erieview 1, University-Euclid 1 and Gladstone, that represented a mixture of rehabilitation, clearance and redevelopment for residential and commercial use.

Cleveland’s General Plan of 1949 under the City Planning Commission of Chairman Ernest Bohn and Director John T. Howard, provided a framework for what was intended to be a redevelopment of the city. The Plan focused on “protection, conservation and redevelopment…aimed at establishing good living standards for every home neighborhood in our city and making decent housing available for all families at prices and rents they can afford to pay”. A critical component of this plan would be slum clearance and it was estimated that 13,000 Clevelanders would have to be relocated from lands and neighborhoods.

Through the Housing Act of 1949 the city was authorized to purchase property in designated blighted areas in order to clear it and sell it to private developers at a reduced price, with the federal government absorbing much of the true cost of the project. The overall intention of the program was to spur construction of improved low-income, public housing in targeted areas, Unfortunately newly constructed housing units never numerically equaled the destroyed units and urban cores struggled to entice people back to the inner city.

Bolstered by the 1954 Berman v. Parker decision of the Supreme Court that expanded the scope of eminent domain (the power of the government to take private property in return for reasonable compensation) and its applicability in urban renewal projects, planners and housing reformers had a powerful tool with which to reshape American cities and society. As planners correlated blighted neighborhoods with public nuisance, and condemnation and re-development with the public good, it became easier to justify private property seizures in increasing numbers. Once coupled with the incentive provided by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 that provided for a system of 41,000 miles of roadway to be financed through a Highway Trust Fund (developed through the excise tax on fuel and tires), the partnership between urban renewal and highway construction became solid.

In the early 1960s Tremont was one of eight targeted neighborhoods in Cleveland for the neighborhood Improvement Program that had developed from the City’s Workable Program of the late 1950s. These programs were designed to control the spread of blight and slums. Blighted parcels and slum neighborhoods could be defined by states of deterioration, age and obsolescence, inadequate provision for ventilation or open spaces, unsafe and unsanitary conditions, overcrowding of buildings on the land and excessive dwelling unit density.

Tremont, through its age, primary population and historic function, fell into this definition of a blighted neighborhood and its voluntary participation in the Workable Program signaled its willingness to authorize a certain amount of clearance and redevelopment as was intended by the program.

Howard Whipple Green’s census of 1954 revealed that 87 to 100 percent of the housing stock in 8 of the 9 tracts that comprised Tremont was built before 1920 and that no new housing was being built. In 1960 the 8459 housing units in Tremont included more than 300 “miscellaneous” dwellings that were often shacks or conversions.

Neighborhood destruction in Tremont for freeways began with the Innerbelt Bridge at Abbey Avenue and West 14th Street in 1941. Unlike their southern neighbors of Brook Park (who unsuccessfully resisted the planned path of the freeway), Tremont did not wage a sustained campaign against the Medina Freeway (I-71). The residents seemed to belong to several schools of thought: one group was ready to leave and willing to accept any fair price for their property to sell it, they were ready to leave the crime, congestion and pollution of the neighborhood and perhaps move further south into cleaner, less dense suburbs such as Parma.

Another group was nervous about the change but did not want to stand in the way of “progress” and a third group, made up of the poorest of Tremonters would see their lives torn apart as their neighbors left and the businesses they had frequented for years closed. Residences with several generations were split up as they did not receive enough money to buy new houses to accommodate their family size. The sense of community, the familial ties, social capital were all taken from this group.

By the 1970s the massive slum clearance and forced relocation approach to urban renewal was becoming less popular with governments and the public. Revolts in such cities as San Francisco, New Orleans and Shaker Heights, Ohio had successfully fought against interstates plans in their areas. Highway construction enthusiasts like Albert Porter’s highway vision would not extend to Shaker Heights and this defeat signaled the coming decline of the supremacy of this urban planning phase.

The Tremont area’s historic importance lies in its being one of the oldest and most densely built neighborhoods in Cleveland- the very qualities that are compromised by large scale land clearance. Its settlement also reflects the broader national pattern of industrial progress and immigration. Tremont was the site of the largest of Cleveland’s seven Civil War camps, Camp Cleveland, and it is included as part of the Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor.

Tremont is also listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is a local landmark as proof of its representation of a pivotal period in U.S. history. The architectural richness of the residences that reflect several styles and the historically ethnic church stock (including landmarks such as the United German Evangelical Protestant Church, the Holy Ghost Byzantine Catholic Church and St. Theodosius) are important visual links to the development and history of Cleveland.

The crusade of using highway construction as a tool in the scheme of progress known as urban renewal and slum removal has lost some of its moral urgency and authority, but there still remains the thought that improvement for economically challenged neighborhoods consists in highway construction and resident displacement. Whether Tremont’s history will influence future decisions on the unintended costs that come with this sort of progress remains to be seen. Perhaps the story of Tremont will come to mind as we debate the merits of such projects as Opportunity Corridor and consider the value of people space versus car space, and investigate how much of our land should be dedicated to going somewhere instead of being somewhere.

Tour: “Tremont: East European Immigration”

From Cleveland Historical/CSU

Historical Tour: Tremont’s Lincoln Park Area

A historical tour of Tremont’s Lincoln Park area from Cleveland Historical/CSU

Tremont from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Tremont from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

TREMONT is an industrial/residential neighborhood on Cleveland’s near west side. Its boundaries include the CUYAHOGA RIVER to the east and north and Valentine Ave. to the south. Originally part of BROOKLYN (Old Brooklyn) Twp., the area was a section of OHIO CITY (CITY OF OHIO) from 1836-54. In 1851 a group of prominent citizens founded CLEVELAND UNIVERSITY in what was then called Cleveland Hts. The institution lasted only until 1853 but its buildings were later used by 3 other educational endeavors, including theHUMISTON INSTITUTE and Western Reserve Homeopathic Hospital, predecessor to HURON RD. HOSPITAL. Lincoln Hts. succeeded Cleveland Hts. and Univ. Hts. as the name for the neighborhood; only with the construction of Tremont School in 1910 did the neighborhood officially get its most recent name. Tremont’s industrial base began with the establishment of the LAMSON AND SESSIONS CO. in 1869 on Scranton Rd. It and numerous later enterprises provided employment to many new immigrants who settled in the area, including IRISH andGERMANS in the 1860s; POLES, 1890s; GREEKS and Syrians (see ARAB AMERICANS), 1900s; displaced UKRAINIANS, 1950s; and Puerto Ricans (see HISPANIC COMMUNITY) in the 1960s. A total of 30 nationalities have lived or were living in Tremont as of 1994.

Complementing the neighborhood’s ethnic variety is its architecture. Many churches are on state and/or national historic landmark registers, including ST. THEODOSIUS RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CATHEDRAL (1912), Pilgrim Congregational (1893), St. Michael the Archangel (1888), and St. Augustine Roman Catholic (1896). By the 1980s, however, Tremont was a run-down, isolated neighborhood in which 68% of the housing had been built before 1900. The population shrank from 36,686 in 1920 to 10,304 in 1980. Closing of the Clark Ave. Bridge and construction of highways I-71 and I-490 cut the area off from the rest of Cleveland. MERRICK HOUSE SOCIAL SETTLEMENT, founded in 1919 as a neighborhood settlement, served as a community focal point for Tremont, and the Tremont West Development Corp. was organized in 1979 to revitalize the area through rehabilitation of housing and neighborhood economic development. Citizens also helped to renovate LINCOLN PARK in the 1980s. By the early 1990s, Tremont was also known for its diverse restaurants and a growing artists’ community.

The Tremont History Project

The beginnings of a great web site on Tremont History

Cultural diversity paints Tremont’s colorful history

Brief history of Tremont written by Chris Marcinko

Cultural diversity paints Tremont’s colorful history

by Chris Marcinko

Civil War Camps to Condos

From Civil War Camps to condominiums, from arsonists to artists, from steel mills to social workers, Tremont and its immigrants have painted a colorful and diverse history.

In a way, this small neighborhood is a microcosm of Cleveland and the forces that have shaped the country. Settling of the land, the rise of industry, a tidal wave of immigration, conflicting religions, and rising social problems are all reflected in Tremont, which is almost as old as Cleveland itself.

Tremont’s borders are the Cuyahoga River on the east and north, and Clark Avenue, or the Harvard Denison Bridge on the south, depending on who you ask. The western border is not universally agreed upon either, I-71 or Scranton Road.

Tremont initially was part of Brooklyn Township and Ohio City from 1836 – 1854, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. It was officially incorporated into Cleveland in 1867.

Although the name Tremont has been used in advertisements since 1837, the neighborhood was known as University Heights and Lincoln Heights. It received its official name in 1910 with the building of Tremont Elementary School.

In 1850 Cleveland University was founded in the area by a group that included the Reverend Asa Mahan, former president of Oberlin College. William Case, a former mayor of Cleveland , and Samuel Starkweather, then the current mayor. The University only lasted five years but for a time the neighborhood was known as University Heights, and some streets are still named Starkweather, Literary, Professor, and University.

During the Civil War the U.S. General Hospital, a military hospital, was located at W. 5th Street and Franklin in the area. In service from 1862 to 1865, the hospital treated more than 3,000 wounded enlisted and non-commissioned officers of the Union and two confederated prisoners.

Immigrant churches

Lamson Sessions Company was established in 1867 on Scranton Road and was the first of many industrial companies to provide jobs for local immigrants.

Immigrants who settled Tremont included the Irish and Germans in the 1860s, Polish, Russian, and Ukrainians in the 1890s, Greeks in the 1900s, more Ukrainians in the 1950s, and Hispanics in the 1960s.

John Grabowski, of the Western Reserve Historical Society, said in a recent interview that ôthe most important and defining changes for the neighborhood were the increase and decline in industry and the diverse immigration flow.ö Grabowski called the neighborhood ô the most ethnically diverse in the county.ö

The diverse ethnic mix is reflected in the area’s 25 churches, which include Immanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church, St. Augustine, Pilgrim Congregational, St. Michael, and Sts. Peter and Paul.

Initially, each church usually served one nationality ù St. John Cantius – the Polish, Our Lady of Mercy – Slovaks, St. Michael – Germans and Slovaks. Today some churches in the area still have their masses read not only in English but also in Spanish, Korean, or Polish to serve their congregation.

Immanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church served German immigrants. Located at 2928 Scranton, the church was built in 1880. Its highest membership was 1420 in 1910, but the church today still has 500 parishioners.

While Immanuel Evangelical was a place of worship and community for German immigrants, St. Augustine served the same purpose for Irish Catholic immigrants. St. Augustine Roman Catholic Church, 2486 W. 14th St., was built in 1894, but was originally Pilgrim Congregational Church. The parish of St. Augustine was formed initially in 1865, but at a different location. St. Augustine parish bought the church in 1896 and is celebrating its centennial at that location.

For a Protestant church to be purchased by a Catholic parish at the time was unheard of,ö said Father Joseph McNulty, pastor of the Church since 1977. ôSince then, both churches have had a close relationship and continue to work well together.

While the parish was Irish, its first pastor was a Frenchman, Father Pierre Gerard-Mogen. At the time pastors were usually the same ethnicity as their congregations, one more example of Tremont’s diversity and tolerance. Father Mogen died of small pox at the turn of the century.

The parish has a history as a center for the Irish and the diocese. During the last century most local Irish immigrants worked on the Cuyahoga River, on the railroad, and at steel mills. In the 1890s about 400 families, predominantly Irish, belonged to St. Augustine.

For more than 30 years, St. Augustine has been a magnet center for the diocese’s less fortunate. In 1964 the church was selected as the diocesan church for the deaf, in 1972 for the blind, and in 1992 for the handicapped and mentally ill.

Community continues to change

McNulty said one of the biggest changes in Tremont was the building of the inter-belt in the 1970s. McNulty, having been with the parish since 1972, said that ômany beautiful houses were destroyed.

While change is a constant, not everyone is willing to accept it, he said. However, most residents of Tremont are very ôopen to new ideas and people.

A small but significant problem is the gangs which gravitate towards W. 6th,ö he said. ôThese kids probably join gangs because older members of their families were in them.

McNulty also said that other problems include ôthe lack of high school diplomas and the abundance of single parents and poverty. Many people face the struggle of moving up and often suffer from despair.

Perhaps the parish’s greatest contribution to this problem and the community is the Hunger Center. Started approximately 30 years ago, the center initially fed 450 to 600 a day. That figure today is closer to a 1,000 served a day towards the end of the month, McNulty said. He added that there is greater demand at the end of the month because government assistance is usually given at the beginning of every month.

Pilgrim Congregational Church, 2592 West 14th St., also is a home for many community activities. It is the location for Arts Renaissance Tremont, which sponsors Sunday concerts that feature music varying from religious and classical to chamber and jazz.

The church also sponsors Theater Labyrinth, a group that produces socially challenging plays,ö according to Reverend Craig Schaub, associate pastor.

After-school programs for children, including scouting, are sponsored by the church. The congregation boasts Cleveland’s oldest Boy Scout Troop. Besides assisting in St. Augustine’s hunger program, the church has classes for parenting, women’s issues, nursing, and also is active in Habitat for humanity. The church also hosts the Tremont Community Forum, which focuses on safety and residential cooperation with the police.

We want to remain a church of and for the community, actively involved in issues, giving voice to those whose voices are on the margins, Schaub said. he went on to say that those marginalized include the poor, the elderly, children, and renters.

Small town atmosphere

Schaub said the Tremont neighborhood was structurally organized to keep residents in touch with downtown and each other. Although right nest door to downtown, Tremont has a small town atmosphere.

The architecture of the churches, Lincoln Park itself and the passion of the people make Tremont a unique, fascinating place, Schaub said, adding that the arrival of artists is a gift to the community.

St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church, located at 3114 Scranton Rd., was originally German but is now predominantly Puerto Rican.

When the church was built in 1892, it was specifically designated as a German only church by the dioceses, according to the pastor, Father Dennis O’Grady. This status remained until 1948.

Father O’Grady himself has a long family involvement with Tremont. having been with the church for 30 years and Pastor since 1980, O’Grady, 63, had a grandmother who was a mid-wife that lived and worked in Tremont.

Sts. Peter and Paul Catholic Church, located at 2280 West 7th St., and built in 1910, was the first Ukrainian church in the Cleveland area. With a preserved liturgical tradition dating back 1,000 years, the church at its height had a membership of a thousand families. With many moving to such suburbs as Lakewood, Parma and Strongsville, church membership has shrunk to 140 families.

According to Father Stephen Zirichny, pastor since 1990, the parish assists the St. Augustine Hunger Center every year, as well as, sending funds for food and medicine back to the Ukraine itself.

This is an older ethnic neighborhood, Zirichny said, but there are new businesses, cafes, and housing and an improving standard of living.

Safety is a concern, but I wouldn’t say it’s a dangerous neighborhood to live in, he said.

Community Organizations

The oldest social welfare institution has a vital connection with religion. Merrick House originated from the Cleveland Catholic charities and the Christ Child Society in 1919.

Currently, Merrick House offers English and citizenship classes, GED tutoring and classes, community development, a meals program, day care, & recreation for juveniles.

The most satisfying part of my job is watching the neighborhood solve its problems and people taking control of their lives, said Gail Long, executive director of Merrick House since 1988.

Merrick House’s budget is more than half financed by the federal and state government but we have already lost much in the way of funding, explained Long, who has been with Merrick House since 1972. Many more contributors were private individuals or organizations such as United Way.

Once we had 90 percent funding from United Way, but this has decreased to 30 percent, said Long.

And this Welfare Reform Bill signed by Clinton is only going to create more problems around here, she said. The lack of welfare benefits, she said, would increase the number of people looking for help at Merrick House, which already is in a position where ôwe are always needing to raise money.

Everyone has the impression that people who need help are lazy and shiftless, she said. That is simply not the case. Many who receive services have jobs, but low paying ones without benefits, she said.

Despite all of this, Long hopes that Merrick House remains an important part of the community.

On the positive side, Long said that Tremont is economically diverse, more integrated, and clearly a place where people want to live. She cited new housing development as examples.

A key part in this revitalization of Tremont has been the Tremont West Development Corporation. Tremont West, originally affiliated with Merrick house, became an independent entity in the early 1970s in the wake of a growing number of arsons committed by landowners seeking insurance money.

The purpose of Tremont West is to improve and maintain the culture and business of Tremont through programs and partnerships with businesses and banks, said Emily Lipovan, executive director of Tremont West since 1993.

Tremont West hosts the annual Tremont Art Walk and has been involved with the Tremont Ridge development and the conversion of Lincoln Park’s bathhouse into condominiums.

Tremont is a mosaic, said Lipovan, who has been with Tremont West since 1991. It has a little bit of everything – churches, ethnic and economic diversity. This is not a sterile environment.

She said that community activism is reflected in the work of 10 block clubs.

Community activism is what the Tremont Opportunity Center is all about. Founded in 1964 as part of the Council For Economic Opportunity, the center received its current name in 1968.

We provide direct social services, said Donna Peters, director since 1989. These include food distribution, assisting people with furniture purchases, youth programs such as science and math clubs, 4-H, and field trips for kids in the summer to such places as the art, health, and natural history museums, Adventure Place, Geauga Lake and others.

The center also has programs for adults, such as computer classes, helping people find jobs, and emergency housing and energy funds.

Altogether the center assists about 250 to 300 families a month. Six work at the center full time, including Peters.

Peters, who has lived or worked in the neighborhood for more than 25 years, said helping someone getting a job or feeding childrenö is the most satisfying aspect of her job.

This summer we had a troubled teen in some of our youth programs, he was anti-social. When the summer programs ended, he was a nice young man. This is a rewarding experience.

Most of their funding comes from Community Services Block Grants from the state and federal government.

For years we have received the exact same amount of funding, which, when inflation is factored in, is actually less and less every year. This new welfare bill means we will have more work ahead of us and not have the funds to match, Peters said.

There is so much propaganda about welfare. Many of the people we help have low-paying benefit-less jobs.

Despite problems, Peters said, the neighborhood itself, is like a small town. I love it here. It feels like home.

Concern about crime

It’s an up-and-coming neighborhood, said Jim Noga, owner of Noga Floral, at 2668 West 14th St.. Noga, 59, business owner for 34 years and a life-long resident of Tremont, has seen many changes in the neighborhood. Residents, old and new are the real strengths of this neighborhood, Noga said. He lives in a century-old building.

He said crime is a problem but I think things have improved in the last few years. Noga said that his business has been broken into a few times and ôsome people might be afraid to go out around here at night, but I’m not, probably because I’ve lived here so long.

He too added grimly that the welfare reform bill just passed might cause trouble because ômore people might resort to crime if they’re hungry.

The crime issue also concerns Councilman Gary Paulenske, who represents most of Tremont in Ward 13. With the housing projects so close to the freeway the result is drive-through take-out drug shops.

More police enforcement would be nice, but the Second Police District has done a tremendous job with what it has, Paulenske said. He added that education was needed in addition to enforcement because even if we had 1,700 police in the area, we would still have a drug problem.

On the positive side, Paulenske said that Tremont is unique, a melting pot, independent, unlike any neighborhood because every kind of ethnicity and economic level is represented, as well as stunning architecture.

People here are outspoken, he said. They are willing to organize, petition, rally, or show up at council meetings or courts on any subject that affects them, from noxious fumes, and unruly neighbors, to crime. This can be a double-edge sword for a politician. You love to see people involved, but invariably, you, as the elected official, get blamed for everything.

New arrivals

The most recent and most rapidly-growing group of residents in Tremont is the artistic community. This includes painters, sculptors, graphic and interior designers, jewelers, poets, musicians and dancers. The artists total about 100, according to Christine Uveges, co-owner of Contrapposto Art Gallery and Econo Studios.

This influx of artists did not occur overnight though. Uveges said that the artists first settled in Tremont about 10 to 12 years ago, and have steadily increased ever since. They mostly hailed from the Flats and Coventry.

Why Tremont? Because of the close proximity to the Flats and downtown. Tremont has an artistic atmosphere, a creative buzz in the air. We’re getting a reputation as a good, creative place to be. This has a snow ball effect. Property values at the time were also inexpensive, Uveges said.

Uveges, who predominantly renovates the interiors of churches, said that Tremont reminds her of the Buckeye neighborhood she grew up in.

Everyone knows everyone here, and everybody watches out for everybody, she said.

The Future

I’m very hopeful about the future, said Father Joseph McNulty. If people continue to work together, we can overcome the twin problems of poverty and crime.

Right now the neighborhood is in flux, said Donna Peters of the Tremont Opportunity Center. New housing is being developed, and middle to high income residents have moved in, but we still have poor people in the neighborhood. She predicts that the neighborhood will eventually become mostly middle class.

It’ll probably take 50 years for them to reach their development goal, said Jim Noga. More broadly though, Noga believes that Tremont’s future could go one way or the other. If the building owners, old and new, fix up the homes and not become slum-lords we could have a real renaissance. If it goes the other way, the situation could go down further.

Within 20 years the development projects could be very promising, but we have a long way to go, said Councilman Paulenske. “What we need in the next five years is more stores and renovation for streets like W. 14th Street and Professor Avenue. This area needs more businesses, small ones such as laundromats and bakeries and larger ones like grocery stores,” he said.

“We should have the ambition to become Cleveland’s Greenwich Village,” Paulenske said. “There is no reason why Tremont cannot become a Mecca for the eclectic.”

Reverend Schaub, of Pilgrim Congregational Church, also is optimistic about the future. “My hope is for a balance, a respect for diversity, and a collaboration for the community from businesses and residents.”

Tremont has a long glorious history of diversity and community involvement. If its future is anything like its past, Tremont will continue to be a diverse, interesting place to live.

City Hop: Tremont

From CSU Cleveland Historical

This tour was created in conjunction with the Downtown Cleveland Alliance for the Sparx City Hop on September 10, 2011. It goes around the perimeter of Lincoln Park, visiting the churches and other historic buildings in this area.

Tremont From Fresh Water Cleveland

Section on Tremont from Fresh Water Cleveland