Ohio Dumps the PARCC Common Core Tests After Woeful First Year (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

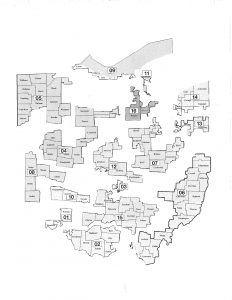

U.S. Supreme Court Ruling Clears the Way For Ohio Congressional Redistricting Reform (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

U.S. Supreme Court Overturns EPA Rules That Closed Coal Fired Power Plants (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Developers “Dream” Venture Could Be Big for Lakefront (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Ohio Online Charter Schools Not Accountable for Students Who Do Poorly in First Year (Akron Beacon Journal)

Retiring Flags and Symbols of the Confederacy: Editorial (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

U.S. Supreme Court Legalizes Gay Marriage Nationwide; Overturns Bans in Ohio and Other States (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Reaction to Gay Marriage Ruling (Dayton Daily News)

Stricter Rules For Ohio Teen Drivers Begin in July, 2015 (WBNS-Columbus)

Ohioans to Keep Health Insurance Subsidies After Supreme Court Ruling (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio House and Senate Conferees Reach Deal on Ohio Budget (Columbus Dispatch)

Can Cleveland Learn From Cincinnati’s Long Road to Police Reform? (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

How Millennials Are Reviving Cleveland (Atlantic – City Labs)

Cleveland Tech Companies Search For Creative Ways to Fill Talent Gap (Freshwater Cleveland)

Alta House and Cleveland Montessori Join Forces to Give New Life to a Little Italy Landmark (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Toxic Algae Blooms Worsen For Lake Erie After “Significant Spike” in Phosphorus, Rainfall (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Republican Districts Receive Most Obamacare Subsidies (Dayton Daily News)

Akron’s Jewish Community Tries Crowd Funding For Cemetary Upkeep (Akron Beacon Journal)

Pittsburgh Mayor Releases Plan to Increase the City’s Population (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Kevin Kelley on What’s to Come For Cleveland City Council (Cleveland Scene)

Cuyahoga County Council Plans to Again Ask Voters to Change Makeup of Audit Committee (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Residents Fume as Streets Crumble (Toledo Blade)

Ohio May Allow Phone Companies to End Landline Service (Dayton Daily News)

Is it Safe to Swim in Lake Erie? Here’s How to Find Out (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Assigning a Lake Erie Algae Fix (Columbus Dispatch)

Change in Funding Formulas Vexing School Officials (Toledo Blade)

Cuyahoga River: Rising From the Ashes, New Life for Cleveland’s Burning River (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Could See “Historic Convention” in 2016, Says NBC’s Chuck Todd (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Bowling Green State University May Unplug Its Public Televsion Station (Toledo Blade)

Budish, Kraus Discuss County Cooperation (Cleveland Jewish News)

Epicentre of the Great Recession: What Happened to Cleveland’s Slavic Village? (the Guardian)

Cleveland City Council President Kevin Kelly Talks at the City Club: Video (City Club)

Mapping Brain Gain and Loss: New Study Charts Changing Faces of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Cavaliers’ NBA Finals Huge For City, Businesses (WEWS)

“Rigged” Charter School Ratings Need Immediate Fix, Charter Critics and Backers Say (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Water Quality Advisories Remain in Effect at Edgewater Park, 19 Other NE Ohio Beaches (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

How to Cut the Cost of Poverty in Northeast Ohio, to the Health of Kids and the Community (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

New Owners of Huntington Building to Spend $280 Million to Convert into Apartments and Other Uses (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

West Side Market Faces Changes to Parking, Days and Hours (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Eaton Corp. Announces New CEO; Current CEO Alexander “Sandy” Cutler to Retire May 31, 2016 (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Saved: Ohio’s Historic Tax Credits (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Ohio Schools Are Facing a Shortage of Bus Drivers (WKSU)

County Prosecutor Releases New Details on Tamir Rice Investigation (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

What’s Cuyahoga County Doing to Promote Regionalism? (WKYC)

Port of Cleveland Finding Success in Shipments to Europe (Associated Press)

Want Better Politicians? Change the Way They Are Chosen: Editorial (Detroit Free Press)

The Beaches Are Inviting, but is Lake Erie Clean Enough to Swim in? (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Milwaukee is Betting Big That Water is Fuel For Its Economic Engine (Chicago Tribune)

Ohio, Michigan and Ontario Agree to Work Toward Lower Phosphorus Levels in Lake Erie’s Western Basin (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Columbus Dispatch Eliminates Anonymous Commenting (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Judge Finds Probable Cause to Charge Officers in Tamir Rice Death (New York Times)

Karamu House Marks Its 100th Anniversary (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Senate Moving to Approve Online Voter Registration (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Lakefront Projects Show Solid Progress But Fall Short of a Transformation: Steven Litt (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Bacteria Making Some Ohio Beaches No Vacation (Columbus Dispatch)

Are New Policies at Cleveland’s Most Diverse High School Helping Hispanic Students or Leaving Them Further Behind? (Cleveland Scene)

A Walking Coffee Tour of Downtown Cleveland (Sprudge)

Ohio’s Economy Strongest Among Great Lakes States (Columbus Dispatch)

5 State Great Lakes Region Lags Almost Every Other U.S. Region in 2014 GDP Growth (U.S. Department of Commerce)

If Supreme Court Rules Against Obamacare, Few States are Ready For the Fallout (Los Angeles Times)

What’s the Republican Convention Going to Be Worth to Cleveland?(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Leaders Bypass Prosecutors to Seek Charges in Tamir Rice Case (New York Times)

More Than 400 Ohio Students Graduate From High School With a Diploma and an Associate Degree (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Bankruptcy or Annexation Appear Most Likely Solutions to East Cleveland’s Financial Woes (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

In Cleveland, Offering Choices to Help Kids Graduate (NPR)

Ohio Shale Gas Production Nearly Triple Over Last Year (Wheeling Intelligencer)

Mother Holmes Had Big Presence at Detroit Council Meetings (Detroit News)

The Saga of Akron, Ohio, a City That Will Wind Up With Three Different Mayors This Year (Washington Post)

City Planning Commission Approves Cleveland’s First “Parklet” (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

State Lawmakers Eye Process to Amend Ohio Constitution(Ideastream)

Fighting Blight in the ‘Burbs (FreshWater Cleveland)

Five Important Things to Know About Affordable Care Act in Ohio (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Krumholtz Zeroed in on Inequality 40 Years Ago (Cleveland Leader)

Appalachia is Being Hammered By the Fall of Coal (PRI)

State to Shut Charter Schools in Cleveland, Canton (Columbus Dispatch)

Big Internet Companies Want Big Wind to Make Their Electricity, Even in Ohio (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Columbus Dispatch is Sold. Wolfe Family Had Owned it For 110 years(Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Lakefront Construction, Long a Dream, Could Start in September (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

An Estimate of How Much Cleveland Will Pay to Reform Its Police Department Under the Federal Consent Decree (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

University of Akron Received Approval to Offer Less-Expensive General Education Classes (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Shale Production Rising Despite Low Prices (Columbus Dispatch)

Two Meetings on Thursday 6/4 Will Detail Latest Visions For Uniting Cleveland with Lakefront (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Amid Fracking Boom, Cities Fear Explosive Safety Risk They Can Carry(Toledo Blade)

Ohio Gov. John Kasich on “Meet the Press” on 5/31/16: Continues to Hint at 2016 Run For President (NBC)

Charter Schools Misspend Millions of Ohio Tax Dollars as Efforts to Police Them are Privatized (Akron Beacon Journal)

Northeast Ohio’s Tale of Two Trauma Centers (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Proposed Trail Around Great Lakes Would Be World’s Longest (Toledo Blade)

Ohio Losing the Battle Against Heroin (Zanesville Times Recorder)

Will Cleveland Root For Police Reform?: Connie Schultz (Politico)

News is Mixed in Detroit, Another City Under Federal Consent Decree(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Amazon’s Plans in Ohio Go Beyond Three Data Centers (Columbus Dispatch)

Amazon to Start Collecting Sales Tax on Purchases in Ohio on Monday June 1 (Dayton Daily News)

Here’s What We Can Expect in the Months Leading Up to the 2016 Republican National Convention (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Millennials Reject Home Ownership For Different Reasons in Texas, California and Ohio (Marketwatch)

New Poll Finds Tight Competition For Final Spots on the Cleveland Debate Stage (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Rents in Ohio Make Housing Unaffordable For Many Low Income Households (Norwalk Reflector)

Summer Concert Season Seen as Boon to Pittsburgh Economy(Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Shipwreck Discovery May Lead to Great Lakes Treasure (Detroit Free Press)

Community Policing at Center of Cleveland Police Reform Plan(Associated Press)

Cuyahoga County Grapples With Loss of Lead Funding (Ideastream)

Planners Seek to Avoid Lining Opportunity Corridor With “Lowest Common Denominator” Development (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Gov John Kasich on Campaign Trail: “No Need For Right-to-Work Law” (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson and Justice Department Agree to Cleveland Police Reforms (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Reaches Settlement With Justice Department Over Police Conduct (New York Times)

Ohio Governor: “We Should Look at Cleveland as a Model” After Response to Brelo Verdict (Washington Post)

Youngstown, Ohio Reinvents Its Downtown (New York Times)

Cleveland Police Officer Michael Brelo Not Guilty on All Charges (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Police Officer Acquitted of Manslaughter in 2012 Deaths (New York Times)

Cleveland Officer Acquitted in Killings of Unarmed Pair Amid 137-Shot Barrage (Washington Post)

What Clevelanders and Others are Saying About Officer’s Acquittal in Death of 2 Unarmed People (Associated Press)

East Cleveland Residents Meet, Diverge From Merger Narrative(Cleveland Scene)

Ohio Unemployment Rate Up to 5.2%: 5 Thngs You Need to Know(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Will Cleveland Riot if a Police Officer is Found Not Guilty? (Washington Post)

Akron-Canton Airport Encounters Turbulence (Akron Beacon Journal)

Black Ohio Lawmakers Say Reforms Needed to Rebuild Trust in Ohio’s Justice System (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Learning From Slavic Village: a Report From Ground Zero of the Foreclosure Crisis May, 2015 (Belt Magazine)

USDA Recognizes Ohio City Farm as National Model For Urban Agriculture (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Developer Plans to Turn a Vacant Foundry into a Fish Farm and Arts Complex on Cleveland’s East Side (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cheap and Fast, Online Voter Registration Catches On (Ideastream)

Cleveland Cavaliers and the Other 3 Teams in NBA’s Final Four Are “Believers” in Analytics (ESPN)

Weather Swings Hurt Ohio Fruit Farmers (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Phaseout of Tax Still Hitting Schools Finances (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Officers’ Silence Frustrates Prosecutor in Police Trial (Los Angeles Times)

Parents Can Keep Kids Home After Brelo Verdict, If They Think It’s Safer, Cleveland Schools Say (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Won’t Riot Again if People Study the Lesson of the Past: Phillip Morris (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

State of Ohio Has Growing Problem With Aging Prisoners (Youngstown Vindicator)

Scrap Common Core Tests? Not Likely in Ohio (Bucyrus Telegraph Forum)

Confusing Formula For Ohio Charter School Funding (StateImpact)

Does Cleveland Need University Hospitals’ New Level 1 Trauma Center?(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Battle is Brewing Over Extension of Term Limits (Columbus Dispatch)

Bike Accidents Raise Mandatory Helmet Issue (Dayton Daily News)

Ohio Auditor Wants to Make it Harder to Amend Ohio Constitution(Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Students Are Less Prepared For College, Career. Report Says(Columbus Dispatch)

The Quiet Struggles of Ohio’s Rural Hospitals (Columbus Business First)

Cleveland Schools Object to Voucher Expansion (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

In Cleveland, Young and Old Keep Tempo of Life (New York Times)

Cleveland Schools CEO Eric Gordon Near Agreement on Four-Year Contract Extension (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio to Have Sales Tax Holiday August 7-9, 2015 (Fox-8)

Federal Judge Issues Order Forcing Army Corps of Engineers to Dredge Cuyahoga River Shipping Channel (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Accusations of Academic Fraud, Abuse and Bullying by Ohio Educators Spiked in 2014 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ban Sought on Tiny Plastic Showing Up in Great Lakes (Detroit News)

Cleveland Art Museum Returns 10th-Century Statue to Cambodia(Toledo Blade/Associated Press)

Akron Mayor Plsquellic’s Legacy and Temperament Made Their Mark(WKSU)

Why Akron’s Mayor Resigned (WKSU)

Evolve or Die: How the Arts Are Courting Young Crowds (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Series A Investors Lacking in Cleveland Region (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Asks Neighboring States to Help Fight Lake Erie’s Algae(Associated Press)

Bill Would Require Ohio Children to Wear Bike Helmets (Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum/Columbus Dispatch)

Akron Mayor of 28 Years Resigns; Blames the Akron Beacon Journal(Akron Beacon Journal)

Technology Edging Out Humanities at Ohio Colleges (Columbus Dispatch)

University Hospitals to Open Level 1 Trauma Center on Main Campus to Serve East Side (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio State Freezing In-State Costs (Columbus Dispatch)

If Punishing Poor Kids is How the Ohio Senate Can Please Gov John Kasich, the Choice is Not Even Close: Brent Larkin (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Seven Things We Know and Don’t Know About MetroHealth’s Transformation Plan (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Farm Bureau Seeks to Increase Farm Tourism in Ohio (Sandusky Register)

Cleveland Bike Share Could Grow to More Than 700 Rentals by Summer 2016 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Losing a Hospital in the Heart of a Small City (NPR)

Battle Looms Over Oil and Gas Drilling in Public Parks (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Election Results From Tuesday May 5, 2015 Primary (Fox-TV)

School Levies Pass at Highest Rate in Decade Statewide (Columbus Dispatch)

Algae Makes Lake Erie More Vulnerable to Asian Carp (Detroit Free Press)

Here are the Statewide Tax Issues You’ll See on Tuesday’s Ballots(StateImpact)

Jobs, Affordable Housing Lead Worry List in Cleveland Fed Survey(Columbus Dispatch)

Fracking Chemicals Detected in Pennsylvania Drinking Water (New York Times)

Cleveland’s 2016 Republican Convention Plan: Don’t Be Baltimore(Politico)

Ohio’s Elderly Forced to Choose Between Food or Medicine (Columbus Dispatch)

Federal Lawsuit Filed to Stop Ohio Turnpike Money From Going Toward Non-Turnpike Projects (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Indians Have Home-Field Advantage on Recycing (New York Times)

Ohio Quick to Change Its Formulas For School Funding (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland-Akron-Canton Region Among Worst in Nation According to American Lung Association Report (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Shaker High School Student of Palestinian Descent Wins $40,000 “Stop-The-Hate” Essay Contest From Maltz Museum (Cleveland Jewish News)

It Takes a Village. The Plan to Create a Better Glenville (Cleveland Magazine)

New K-8 International School at Cleveland State Delayed Until 2017(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland’s “Jock Tax” Ruled Illegal by Ohio Supreme Court (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Clinic Worth $12.6 Billion to Ohio, Report Says (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Gov. Orders Minimum Standards For Police Departments to Improve Community Relations (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Summer Weather Forecast: Higher Temperatures and Electric Bills(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Study: Most 8th Graders Score Low on U.S. History, Civics (Akron Beacon Jounral/Associated Press)

Trace the Histories of Greater Cleveland’s Largest Banks (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Teacher Dress Code, Home Visits and Lesson Plan Rules are at Issue in the Cleveland Teachers Dispute (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Port of Cleveland is Riding Swell of Prosperity (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Michigan Teacher Training Programs See Dramatic Enrollment Declines(Detroit Free Press)

Republican Skirmishing Over Ohio Budget is Heading for a Full-Blown Battle: Tom Suddes (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

What Went Wrong in Downtown Toledo’s Demise (Toledo Blade)

How Gay-Marriage Case Was Born of a Divided Ohio (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Gov. Kasich Shares His Vision of Ohio in Washington: 8 Takeaways(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

May Co. Building Developers to Try Again For Historic Preservation Tax Credit (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

The Dirty Secret of College Athletics is That Students Pay Exorbitant Fees to Subsidize It: Brent Larkin (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Playhouse Wins 2015 Regional Theater Tony Award (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

JetBlue Airways Launches Service From Cleveland Next Week (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

East Cleveland Council Seeks “Objective” Options Study (WKYC)

Cleveland Moves Forward With Design of Intermodal Transit Center(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ethane Cracker May Be Built in Shale Gas-Rich Belmont County (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

A Multi-Billion-Dollar Cracker Plant May Be Built in Eastern Ohio(WKSU)

Beachwood May Share Emergency Dispatch With Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, South Euclid (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Does Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Test Miss Its Goal? (PBS)

Taking the Financial Temperature of the Possible Lakewood Hospital Closure (Cleveland Scene)

Harrison Dillard Statue Unveiled: “The Dream Can Be Accomplished”(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Heinen’s and Amish Farmers Meet to Discuss Expanding Local Food Crops (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Shipping Great Lakes Water? That’s California Dreaming (Detroit Free Press)

Anchored in Hope: How Toronto is Learning From Cleveland’s Return to Prosperity (Toronto Star)

Solar Energy Gets Cloudy in Ohio (Columbus Dispatch)

Thousands Sit Out Common Core Testing (Columbus Dispatch)

Legal Challenge to Ohio Early Voting is Settled (Youngstown Vindicator)

Apartment Leasing Starts at Flats East Project on the River (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Job Growth Rate Continues Below National Average (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio 2014 Foreclosure Filings Continue to Decline; Cuyahoga County Down 20.3% vs 2013 (WOUB)

Ohio Rated Worst in Immigrant Policy (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio’s Gov. John Kasich Moves Closer to 2016 Presidential Bid (CNN)

Budish Focuses on Economic Development in His First State of the County Speech (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Full Text of Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish’s 2015 State of the County Address (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Schools CEO Talks the Cleveland Plan, Charters, and the Future (StateImpact)

Oil and Gas Tax Hike is Dead For Now, Lawmaker Says (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Convention Center Report Card (WKYC)

100-Plus Local Governments Respond to Ohio Treasurer Josh Mandel’s Invitation to Post Checkbooks Online (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

First Energy Closes 104-Year-Old Coal Powered Plant in Cleveland (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Region Economy Grew at “Slight Pace”, Fed Reports Show(Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Experts Say Lake Erie Fishing Should Be Productive in 2015 (Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum)

Ohio House to Jettison Chunks of Kasich Budget in Favor of Its Own Plan(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Republicans Plan to Scrap Gov. Kasich Controversial Tax Plan(Cincinnati Enquirer)

Hospitals Leave Downtowns For More Prosperous Digs (MedPage Today)

Ohio Gov Kasich “Seriously Considering” Run For President (Columbus Dispatch)

State School Board Vote Eliminates Minimum Number of School Nurses, Librarians, Counselors, Arts Teachers (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

New Entertainment Districts Proposed For Some Ohio Cities (Youngstown Vindicator)

Ohio Gov. Kasich: “Jeep is Critical For Us” (Detroit Free Press)

County Executive Budish Envisions a Different Approach For Cuyahoga County (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

A Tale of Two Clevelands: Richey Piiparinen (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Female Tech Entrepreneurs Alter the Landscape in NE Ohio (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Appalachian Communities Scraping By as Coal Taxes Drop (Wall Street Journal)

Cuyahoga County Announces Recipients of $10 Million to Demolish Vacant Buildings (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

No Need For Religious-Freedom Law in Ohio, Gov Kasich Says(Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Officials Propose Funding a Plant For Fiat Chrysler in Toledo (Wall Street Journal)

Gas-Fired Power Plants Sprouting in Ohio to Replace Old Coal-Burners(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Sues U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Over Toxic Sediment Plan(Associated Press)

LaunchHouse Targets Teen Entrepreneurs as Its New Focus (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

“Unprecedented” Rise in NE Ohio Homeless Families (WKYC)

Ohio Continues to Bear Marks of the Civil War (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

County Council Members Put Distance Between Themselves and County Executive’s Debt Talk (Cleveland Scene)

Ohio Treasurer Invites Local Governments and School Districts to Put Their Checkbooks Online For Public Review (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

First Year of PARCC Testing Was No Picnic for Ohio Schools (Columbus Dispatch)

Rural School Districts Rip Gov Kasich Education-Funding Plan(Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland and Pittsburgh: A Tale of Two Sewer Districts (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Ohio and Other Appalachian States Slammed By Environmentalists For Lack of Fracking Oversight (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Economic Impact of Drones Will Be Huge in Ohio (Columbus Dispatch)

What is Ohio Doing to Stop Toxic Algae? (Port Clinton NewsHerald)

Ohio Gov. Kasich Vetoes Provision That Made It Harder For Out-of-State Students to Vote (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

East Cleveland Mayor to Begin Circulating Petitions Opening Door For Merger With Cleveland (WEWS – Newsnet5)

Prosecutors: Police Witnesses Uncooperative in Cleveland Shooting(Columbus Dispatch)

NE Ohio Based Progressive Insurance to Offer Insurance to Lyft Drivers(Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Low-Income Working Families Increase (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Lake Erie Algae Relief Years Away (Associated Press/Detroit News)

The Numbers Behind East Cleveland’s Financial Predicament(Ideastream)

Can Out-of-State College Students Vote in Ohio in 2016? (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Public-Private Partnership: Behind the Scenes of the State of the City Address (Cleveland Scene)

Central Ohio’s Population Boom Isn’t Stopping (Columbus Dispatch)

Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish Says “There’s Very Little Capacity to Take On New Projects For Around a Decade or More” (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Legislature Advances Controversial Bill That Could Deter Students From Voting (Huffington Post)

A New Cleveland Lakefront Plan is Refreshingly Pragmatic: Steven Litt (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Euclid Media Group, Owner of Alternative Newspapers Including the Cleveland Scene, Buys St. Louis Weekly (St. Louis Business Journal)

Bill to Reduce Lake Erie Toxic Algae Passes Legislature; Governor Expected to Sign (News-Herald)

Ohio House Passes “Heartbeat Bill” After Emotional Debate (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Will See Largest Economic Impacts Among NCAA Men’s Basketball Regional Host Cities (Forbes)

Tireless Cleveland Music Booster From 1980s and 90s Jim Clevo Dies (Cool Cleveland)

The Long-Distance Relationship Between Americans and Jobs (Wall Street Journal)

Parma Balances 2015 Budget By Closing Pools This Summer (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Proposed 75 mph Speed Limit in Ohio Dead For Now (Dayton Daily News)

Deep Freeze on Great Lakes Halts Cargo Shipments (New York Times)

What Has Gov. Kasich Really Done to School Spending in Ohio? (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Excessive Tests Crimp Lesson Time, Ohio Teachers Say (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Lawmakers Close in on Compromise on Lake Erie Algae (Akron Beacon Journal/Associated Press)

Absentee Voting Season For May Primary Elections Begins Soon (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

In 2016 Test, Ohio Gov. Kasich Trumpets “Ohio Story” (New York Times)

Citizens Fight For the Future of East Cleveland (Fresh Water Cleveland)

5 Observations From President Obama’s Cleveland Visit (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Ranked #1 in Nation For Transparency in Government Spending (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Clinic Grapples With Changes in Health Care (New York Times)

Tom L. Johnson Has “Left the Building” (WKYC)

Irishtown Bend Hillside Needs to Be Fixed to Avoid Collapse, Says Port Authority (Cleveland Scene)

What Are Ohio’s “Most Irish” Cities and Counties (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Considering 75 MPH Speed Limit on Turnpike and Rural Highways (Dayton Daily News)

Masonry Competition Underscores Future Skills Shortage (StateImpact)

New Ohio School Tests Source of Anxiety, Anger (Toledo Blade)

Who Will Run the Manufacturing Industry After the Boomers Retire? (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

To Restore Democracy in Ohio, Slay the Gerrymander: David Kushma, editor (Toledo Blade)

2018 Elections May Highlight the Convoluted Nature of Ohio Politics: Tom Suddes (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Avon Joins Trend of Doing Away With Shop Class (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

President Obama to Speak at Cleveland City Club on Wednesday March 18 (WKYC)

Construction Unions Will Teach Trades to Cleveland Students (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio’s Medicaid Mess; A Systemic Breakdown That the State Must Fix: Opinion (Toledo Blade)

Cleveland’s Rents Soar Ahead of 2016 Republican Convention (CNN MONEY/Fox 8)

Cuyahoga County’s Approach to Collecting Delinquent Taxes Contributing to Blight, According to Study; Delinquencies Have More Than Doubled Since 2009 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Bill to Limit Testing Gets Ohio Educator’s Backing (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Libertarians Face Quagmire in Seeking State, Local Ballot Access (Associated Press)

“Massive Transformation” of MetroHealth Medical Center’s Main Campus Scheduled to Start Later This Year (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Where City of Cleveland Homes Sell For $100,000 or More (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Fellowship of the Inner Ring. Interview with South Euclid Housing Manager (Cleveland Scene)

Cleveland’s CMSD Students at Max Hayes High School Get Path to Construction Jobs (WKYC)

Teachers Tell Ohio Legislators That State Tests Take Too Long (Columbus Dispatch)

Toledo to Sue Ohio Over Traffic Camera Restrictions; City Says New Rules Violate Its Authority of Home Rule (Toledo Blade)

Ohio House OK’s Bill Regulating Fertilizer Runoff. Must Be Reconciled With Different Senate Bill (Toledo Blade)

How Common Core Test Opt-Outs Affect Schools in Ohio (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Fate of Lake Erie Algae Ohio Legislation Not Clear Yet (Associated Press)

The Remodeled Midwest Republican (Bloomberg)

A New Life for Dead Malls (The Atlantic)

Ford Starts Building Newest Engines in Cleveland (USA Today)

Public Square Renovation Starting Monday; Paradigm Shift For Public Space in Cleveland (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Unemployment Rate 5.1%; State Added 25,100 Jobs in January (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Long Lines at the Pantry: Hunger and Need on the Rise in Ohio (Belt Magazine)

Incoming Ohio State Students Must Provide Proof of Vaccinations (Columbus Dispatch)

US Supreme Court to Hear Ohio Gay Marriage Case (USA Today)

Latest Ohio Schools Funding Formula Questioned (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Secretary of State Husted Wants Online Voter Registration Soon (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Evaluating the Actual Design of the Opportunity Corridor (Rust Wire)

Cleveland Mayor Jackson Talks Police Reform, Schools, Possible 4th Term in State of the City Address (WKYC)

Kent State Study Links High Smart Phone Use With Low GPA (Akron Beacon Journal)

Public Square Flashback: Cleveland History as Revealed in the Heart of the City (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Akron Sues to Stop Ohio’s New Traffic-Camera Law (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

The Buckeye Medicaid Boom (Cleveland Scene)

Tamir Rice’s Mom: “No Apology Yet For Killing My Son”: Video (WKYC)

Where Have All the Teachers Gone? (Ideastream)

Could Ohio Set Up Its Own Health-Care Exchange After All? (Columbus Dispatch)

New Report Shows Urban “Donut” Shifting (USA Today)

US Supreme Court Hears Arguments in Redistricting Case That Could Impact Ohio (Columbus Dispatch)

Debate Over Ohio’s Shift From Income Tax to Sales Tax Continues (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Charter Schools Identified as Among Worst in Nation (Akron Beacon Journal)

For Detroit Retirees, Pension Cuts Become Reaity (Detroit News)

Exports From Ohio Hit Record Last Year (Columbus Dispatch)

Hundreds Ask Cleveland to Reopen Police Mini-Stations (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio River Deemed Nation’s Most Polluted (Portsmouth Daily Times)

Cincinnati Icon: Boss Cox (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Plan For Congressional Redistricting in Ohio Proposed (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio National Guard to Be Home For 1 of 3 U.S. Cybersecurity Watchdogs (Columbus Dispatch)

Shale and Gas Production in Ohio: the Numbers Tell the Story (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Severance Tax Debate Has Three Sides (Steubenville Herald Star)

Cleveland Cavaliers Suggest 50-50 Split With Cuyahoga County For Costly Arena Renovation (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

New School Tests Spur Anger, Absences (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Detroit Blight Removal Needs More Money: Detroit Mayor Duggan (Detroit Free Press)

Talk of Recalling Cleveland Mayor Jackson Both Petty and Potentially Damaging: Brent Larkin (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Mayor Recall Won’t Rip Us Up; May Even Raise Cleveland Up: Roldo Bartimole (Cleveland Leader)

Ohio Gov Makes Pitch For More Income Tax Cuts, Shift in Tax Structure in State of the State Speech (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

2015 State of State Speech: Video (Ohio Channel)

2015 State of State Speech: Text (Associated Press)

John Kasich’s Crusade. Is Ohio’s Governor Running For President? (Bloomberg)

NE Ohio Schools Suspend Kids Often; Study Shows Big Gaps Between Blacks, Whites (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Clinic, Veterans Administration to Provide “Seemless Access” to Electronic Medical Records (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

New Cruise Ship to Ply the Great Lakes (Detroit Free Press)

Cleveland Ranks #1 Among “Large U.S. Metros” in Income Segregation: Study (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Opting Out of State Tests Has Costs For Ohio Students, Schools (Columbus Dispatch)

Group Believes Opportunity is Still There For Opportunity Corridor (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Most of Great Lakes Surface Frozen For Second Year in a Row (Associated Press/Akron Beacon Journal)

2016 Ohio Senate Race Already Taking Unpredictable Turns (Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum)

Saving Cleveland’s Poorest Neighborhood (Politico)

Pioneering Black Soldier From Ohio Gets Belated Recognition (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Sprawl Grew the Most in Cleveland, Other Rust Belt Metro Areas (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Online Voter Registration Would Save Money, Reduce Errors, Ohio Officials Say (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Colorful, High Energy Former Columbus Mayor Dana G. “Buck” Rinehart Dies (Columbus Dispatch)

Former Columbus Mayor Buck Rinehart Interviewed by Mike Curtin on 2/27/14: Video (Columbus Metropolitan Club)

Bill Targeting Lake Erie Algal Blooms Passes Ohio Senate in a Unanimous Vote; House Debating a Similar Bill (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Peace Corps Continues to Draw Volunteers From Ohio and Its Colleges (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland’s First Live and Local Internet Radio Station Set to Launch (Fresh Water)

Gov. Kasich Budget Plan Increases Funding to All Charter Schools (Columbus Dispatch)

Ex-Ohio Governor “Testing the Waters” For Senate Bid (USA Today)

Local Governments Cannot Regulate Fracking, Ohio Supreme Court Rules (Columbus Dispatch)

Is the Economic Impact of LeBron James’ Return to Cleveland Real? (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

NE Ohio Retail Vacancy Rate Reaches Lowest Point Since 2007 (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Do Lawsuit Payouts Equal a Pattern of Police Misconduct (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cuyahoga County Again Pays Sports Owners’ Bills: Roldo Bartimole (Cleveland Leader)

Cleveland Black History: Garrett A. Morgan Water Works Plant (WKYC)

Debt of Ohio Public Universities Tops $6.5 Billion (Dayton Daily News)

Manufacturing to Remain Primary Driver of NE Ohio Economic Growth, PNC Bank Report Says (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Pennsylvania Governor Wolf Places Moratorium on Death Penalty in State (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Women in Ohio Earned Less Than 83 Cents For Every $1 That Men Made, Labor Department Says (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Columbus Loses Bid for Democratic National Convention; Philadelphia to Host in 2016 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Gov. Kasich Meeting With Advisors About White House Bid (The Hill)

Tougher Rules for Ohio Charter Schools Getting Widespread Support(Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Gov. Kasich Orders an End to U.S. Corps of Engineers Sediment-Dump in Lake Erie (Columbus Dispatch)

With NASA in the Class, LaunchHouse Graduates Ready to Launch in New Direction (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cloudy Skies For Ohio’s Clean-Energy Industry (Columbus Dispatch)

Allegations of Cleveland Police Misconduct Have No Neighborhood Boundaries: Map (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

America’s Changing Demographics: audio file (Ideastream)

Cleveland Residents, Leaders Frustrated By Unplowed Streets(Associated Press/Morning Journal)

55% of Ohio Voters Approve of Gov. Kasich (Toledo Blade)

Term-Limited Northeast Ohio Lawmakers Mostly Stay in Public-Sector Jobs (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Student Apartments at Playhouse Square’s Edge Win OK from Cleveland’s Planning Commission (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Carl Stokes: A Pictorial Retrospective (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Shale is Suffering in Ohio Due to Declining Oil and Gas Prices (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Arts and Culture Group Seeking Levy Renewal in November 2015 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Farmers Face Shocking Tax Jolt (Columbus Dispatch)

How Metro Detroit Transit Went From Best to Worst (Detroit Free Press)

East Cleveland Mayor Gary Norton Now Open to Merger Discussion(Cleveland Scene)

East Cleveland Mayor Holds Community Meetings on Bankruptcy, Merger(Ideastream)

Number of Uninsured Ohioans Nearly Cut in Half (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio School District Winners, Losers in Gov. John Kasich’s New Budget Plan (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Training Under Way For Cleveland Police Body Cameras (Cleveland Scene)

Lake Erie Algal Bloom State Bill Could Be Law This Spring, Ohio Senators Say (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

President Obama Spending Plan Would Cut Cash For Great Lakes Restoration By $50 Million (Chicago Tribune)

After Nearly 100 Years, Great Migration Begins Reversal (USA Today)

Cleveland City Council Approves Funding For Pedestian Bridge to Lakefront (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio’s Fracking Tax Would Jump Significantly Under Gov. Kasich’s Budget Plan (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Gov. Kasich Wants Hike in Sales Tax, Medicaid Premiums(Cincinnati Enquirer)

Ohio School Districts Facing Cuts in Gov. Kasich Plan (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Near Bottom For Vaccinating Kids (Dayton Business Journal)

Intermodal Center for Buses, Trains to Be Studied (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio, Canada’s Mutually Beneficial Relationship Grows Stronger(Columbus Dispatch)

Longtime Shaker Heights Shopping Center Being Transformed (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Ohio’s Gov. Kasich Stands Up For the Common Core (Daily Beast)

Downtown Cleveland Residential Occupancy Grows; Office Supply Shrinks (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Charter School Legislation Seeks to Improve “Accountability, Transparency and Responsibility” (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Gov. Kasich Proposes Dramatic Cut in Ohio Small Business Taxes (Akron Beacon Journal)

Pennsylvania Bans New Gas Drilling on Public Lands (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

Bumper Crop of Urban Farming Can Be Found in Ohio (Mansfield News Journal)

Home Prices Up For Most of Cuyahoga County in 2014 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland’s Public Square Overhaul Could Begin In February (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

1 Vote Decided 7 Ohio Local Elections in November 2014 Election (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Hospitals Grapple With Readmission Fines (Medpage Today)

Ontario Waste Blamed For Tainted Ohio Drinking Water (Toronto Sun)

Ohio House Speaker Says He Won’t Repeal Medicaid Expansion (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Police Segment on CBS 60 Minutes 1.25.15: Video (CBS)

As Ohio Vouchers Expand, Thousands Remain Unused (Newark Advocate)

Two Years After “Right-to-Work” Laws Pass, Union Membership in Michigan Drops Sharply (Detroit News)

Ohio Jobless Rate Drops to 4.8% in December; Lowest Since 2001(Toledo Blade)

Many Errors By Cleveland Police, Then a Fatal One (New York Times)

Many Ohio Charter Schools Overstated Attendance Rates, State Investigation Finds (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Police Diversity Lags in Many Cities (USA Today)

30 Year-Old Democrat to Challenge Ohio Senator Portman in 2016 (The Hill)

Cleveland State Trustees Agree to Mather Mansion Renovation and Enrollment Goals (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Nearly 1 in 10 Ohio Bridges Found to Be “Structurally Deficient”(WEWS)

Former Congressman Louis Stokes at the City Club in Honor of MLK Day 2015: Video (City Club)

“Equal Treatment” Promised in Historic Pact Signed by Cuyahoga County Juvenile Prosecutors, Judges (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

New Ohio House Education Committee Chairman Wants to Cut Testing and Reduce “Toxic” Talk About Common Core (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Property Tax Rates Are Up in 2015 For Most in Greater Cleveland (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Ranked Among Best Startup Cities in America (Cleveland Scene)

Idea is For Fewer Polling Places, But You Can Use Any of Them(Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Clean Energy Policy Freeze Stalls Investment, Report Says(Cincinnati Enquirer)

Ohio Department of Education Recommends a Cutback on Testing(Ideastream)

Identity Theft Reports Rise in Ohio: Attorney General (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Are Ohio’s Older Voting Machines a Risk for 2016? (Columbus Dispatch)

Nearly All Cleveland Hotel Rooms Are Already Booked For 2016 Republican National Convention (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Republican National Conventon in Cleveland Dates Are Set: July 18-21, 2016 (Ideastream)

“Extraordinary Design” Offered in Proposed Cleveland Skyscraper (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

How Do Ohio Tax Policies Rank in the Nation? (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Secretary of State Wants to Track Absentee Ballots On Line(Toledo Blade)

Cleveland is Enjoying Economic Revival, Federal Reserve Official Says(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Hts Losing 60% of Its Water, Millions of Dollars, in the Ground Beacause of Leaks (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

East Cleveland is Out of Options: Opinion (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

The Oregon Ducks Lost – and Ohio’s Senators Won (Washington Post)

Ohio House Committee Leadership Announced (ohiohouse.gov)

Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Tim McGinty at the City Club Talks About Public Safety in Cuyahoga County: Video 1/9/15 (Cleveland City Club)

Medicaid, Taxes to Dominate 2015 in Ohio (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Hyland, Cleveland’s Largest Software Company, Plans to Hire 200 More in 2015 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Supreme Court Case and US House Speaker John Boehner Delaying Ohio Congressional Redistricting Reforms (Columbus Dispatch)

Plummeting Price of Oil is Weakening Steel Industry (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Great Lakes Teaming With Tiny Plastic Fibers, Scientists Say (Chicago Tribune)

Beefed Up Budget is Big Development for NE Ohio’s NASA Glenn (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Developer Sees Prospect Avenue Apartments as First of Several Cleveland Projects (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Research Links Earthquakes to Fracking Wells in Ohio (New York Times)

First Look at Proposed 54-Story Tower in Downtown Cleveland (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Ohio Schools Earn a “C” in Nationwide Review (Columbus Dispatch)

More Senators Have Come From Ohio Than Any Other State(Washington Post)

Lake Erie Dead Zones: Don’t Blame the Slime! (Live Science)

US Steel Lays Off 756 Including 614 in Lorain Ohio, Blaming Low Oil Prices (Wall Street Journal)

Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish Says He’ll Meet with 100 Business Leaders in 100 Days (Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Racial Divide Widens in Ohio Classrooms. Minority Students Less Likely Today to Be Taught By Own Race (Akron Beacon Journal)

Four Years Later, a County Reformed (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Heavyweight Response to Local Fracking Bans (New York Times)

Ohio Libraries Fear More State Cuts (Marion Star)

5 Key Policy Objectives Ohio Gov. John Kasich Will Likely Pursue in 2015(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Cleveland Seeks Outside Probe of Tamir Rice’s Shooting (Columbus Dispatch)

2015 Northeast Ohio Transportation Projects: Potholes to Superhighways(Plain Dealer/NEOMG)

Total Ohio Traffic Deaths Likely Higher for 2014 (Associated Press/Toledo Blade)