Why Mike Curtin’s retiring from politics

A political scribe’s pen can pack more wallop in Columbus than a politician, especially when the writer is an outnumbered Democrat in the conservative Ohio House of Representatives.

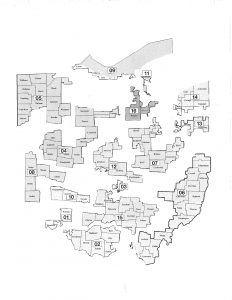

Mike Curtin knew what he was getting into in 2012, when he traded in his reporter’s hat for a seat on Capitol Square. The homegrown journalist who rose from reporter to president of Dispatch Printing Co., owner of the Columbus Dispatch, won election nearly four years ago to the 17th District that covers much of the Hilltop, Valleyview and other down-and-out west side neighborhoods.

Even as a lawmaker, Curtin kept penning political tomes, including recently updating the Ohio Politics Almanac with a third edition.

But legislating is a time-consuming job, especially in one of the poorest districts in Ohio. Curtin, who turns 65 this summer, won’t run for re-election this year so that he can spend more time traveling with his wife and watching his grandkids grow.

“And quite frankly, I want to research and write more,” Curtin said. “If I have a talent, it’s more of a journalistic talent than a policy maker talent.”

Curtin started in 1973 as a reporter at the Dispatch and focused mostly on politics. He rose through the ranks to become the daily newspaper’s editor and eventually vice chairman in 2005. Along the way, Curtin became one of the state’s most respected journalists. He retired in 2007 but consulted with the Wolfe family-owned newspaper until he began his short legislative career.

“I was the Jim Siegel of this place in the early to mid ’80s,” Curtin said, referencing the Dispatch’s current Statehouse reporter.

As a state legislator, Curtin noted just how stark partisanship can be, which he blames in part on gerrymandering. But that’s an obvious analysis for many who follow politics.

More nuanced might be his observation about law enforcement’s diminished status at Capitol Square. In the 1980s and ’90s, police-affiliated groups could flex considerable political muscle when they were united on issues like firearms legislation, Curtin said. Words of caution from the Fraternal Order of Police, Buckeye State Sheriff’s Association, Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association and the Ohio Association of Chiefs of Police carried clout when they urged tighter regulations on guns.

“Today they’re patted on the heads and they (legislators) say, ‘Thank you very much for your input,’ ” Curtin said. “The attitude here is there ought to be no regulations. It’s a national trend in the Republican Party and certainly true here. Just the disdain for regulation – in my view reasonable regulation like background checks – that’s the biggest disappointment and biggest surprise.”

Indeed, a May 8 column by political writer Thomas Suddes identified utilities, banks, insurers, nursing home operators and oil and gas drillers – but not the police – as those with the most influence at the Statehouse.

Curtin thinks expanding term limits would help some of what ails policy making. Since 2000, Ohio lawmakers in both chambers have had their stays limited to eight years, though they can spend more time on Capitol Square through a loophole that allows them to switch between the Senate and House. Curtin would like to see the maximum extended to 12 years, preserving institutional knowledge on complex issues such as energy and the environment that can take up to five years to master.

“In my view we need the Ron Amstutzs, we need the Jack Ceras. We need the people who have the long view and understand how we got to where we are,” he said of the experienced Republican and Democratic representatives.

That’s a part of why Curtin wants to get back into explanatory journalism – taking a public policy issue and reaching back in time to explain how it came to be. He did that in the 1990s during the DeRolph v. State of Ohio school funding debate that ended in the state Supreme Court’s ruling Ohio’s funding mechanism was unconstitutional.

More recently, changing the composition of the Columbus City Council to 13 members from seven and moving to district representation are proposals ripe for the kind of analysis Curtin hopes to provide.