Teaching Cleveland

Northeast Ohio Journalism Hall of Fame

Philip W. Porter

William O. Walker

www.teachingcleveland.org

Technology Creates a Modern Transportation Era For thousands of years, humankind depended on muscle power, animal or human, to move people and goods from one land location to another. that would finally change in the 18th century with the invention of the steam engine. It revolutionized the way in which work was accomplished, and it ushered in the “modern age.” The first successful use of steam power for transportation was the work of John Fitch. In 1787 his steamboat traveled along the Delaware River in Philadelphia. It was Robert Fulton, in 1807, however, whose steamboat Clermont successfully plied the Hudson river between New York City and Albany, that ultimately marked the arrival of the age of the steamboat. While the challenge of using steam to propel shipping along the waterways had been met, it wasn’t until 1825 that its application to land travel arrived. This took the form of a steam locomotive, invented by George Stephenson in England. It was four years later, in 1829, that his Rocket locomotive traveled between Liverpool and Manchester averaging 30 miles per hour. The Rocket proved that steam railroads were the wave of the future. The first steam train serving Cleveland came in 1850. It connected the city to Chicago and New York City.

For thousands of years, humankind depended on muscle power, animal or human, to move people and goods from one land location to another. that would finally change in the 18th century with the invention of the steam engine. It revolutionized the way in which work was accomplished, and it ushered in the “modern age.” The first successful use of steam power for transportation was the work of John Fitch. In 1787 his steamboat traveled along the Delaware River in Philadelphia. It was Robert Fulton, in 1807, however, whose steamboat Clermont successfully plied the Hudson river between New York City and Albany, that ultimately marked the arrival of the age of the steamboat. While the challenge of using steam to propel shipping along the waterways had been met, it wasn’t until 1825 that its application to land travel arrived. This took the form of a steam locomotive, invented by George Stephenson in England. It was four years later, in 1829, that his Rocket locomotive traveled between Liverpool and Manchester averaging 30 miles per hour. The Rocket proved that steam railroads were the wave of the future. The first steam train serving Cleveland came in 1850. It connected the city to Chicago and New York City.

The use of steam locomotives for city transportation, however, was really not feasible. The noise, smoke, and soot that accompanied them made them unsuitable for an urban environment. As a result, the city version of the stagecoach, the horse-drawn omnibus, continued a while longer in cities like Cleveland as the main means of transit.

The use of steam locomotives for city transportation, however, was really not feasible. The noise, smoke, and soot that accompanied them made them unsuitable for an urban environment. As a result, the city version of the stagecoach, the horse-drawn omnibus, continued a while longer in cities like Cleveland as the main means of transit.

The omnibus was faced with its own set of problems. The omnibus mainly had to travel along unpaved streets, which after rain or snow, often became impassable for the clumsy vehicles. thus, the idea of putting the omnibus on rails built in the streets offered real advantages. These street railways, as they were known, were pulled by teams of h

In 1860 the population of Cleveland reached 43,417, an increase of over 250% from the previous census in 1850. The increase in numbers also meant that people were spread over a larger area of the city, making transportation increasingly important. This trend made the investment in street railways ever more attractive. Entrepreneurs interested in laying rails in city streets needed to apply to the city of Cleveland for a franchise. By 1875 nine separate companies were operating street railways in the city. Street railway leaders, however, were not content to continue operating with horse- drawn cars, and so the search continued for a suitable replacement power source.

In 1879 Cleveland inventor Charles Brush had installed electric lighting along Public Square. Its reliability as a lighting source suggested that it might also be the answer to powering the street railways. Two other Clevelanders, Edward Bentley and Charles Knight, gave the idea its first successful trial. On July 26, 1884, a mile of electrified line on Central Avenue was tested. Cleveland became the first city in the nation to have an electricity- powered streetcar line. the Bentley-Knight system, utilizing a trough buried between the rails, encountered problems, especially when rainwater would flood the power conduit. It was discontinued after a month of operation.

Another system was then under development in Richmond, Virginia, the work of Frank J. Sprague. His system brought electric power to the streetcar via an overhead wire. A trolley pole on the car’s roof took in the power and transferred it to the car’s electric motors. It was the Sprague system that proved most effective and was adopted in most cities across the country. Cleveland opened its first Sprague installation on Euclid Avenue, from East 118th Street to East 55th Street, in December 1888. Electrification from East 55th Street to Public Square was completed in July 1889.

Even as electricity brought about the triumph of the streetcar in public transportation, in Germany Karl Benz began building the first automobiles, powered by internal combustion engines. the automobile would soon challenge the dominance of the streetcar, and within 50 years it would become the dominant force in urban planning.

Creating a Transportation System

While electrification represented significant technological progress for public transit, it also meant that additional capital would be needed to build electrical power plants, substations, and the overhead distribution network. Recognizing the advantages of economies in scale, the street railway operators saw an answer in mergers between the separate companies.

By 1893, the various independent lines came under the control of just two companies, the Cleveland Electric Railway Company and the Cleveland City Railway Company. In 1903 Cleveland city railway company merged into the Cleveland Electric Railway Company. The consolidation, however, did not bring peace to the local public transit scene.

By 1900 Cleveland’s population had jumped to 381,768. It was the seventh largest city in the nation. automobile ownership that year was estimated at 150. this meant that public transit was of vital importance to almost every Clevelander, and naturally there were different concepts about how public transit should be operated and managed.

The Cleveland Electric Railway Company was a private company. It viewed its investment in public transit as a sound way to generate dividends for its stockholder. Ridership in 1903 passed the 100,000,000 mark, and with fares set at a nickel, the company was showing a solid profit.

The railway company’s vision about public transit, however, contrasted sharply with that of Cleveland Mayor Tom Loftin Johnson, who led the city from 1901 to 1909. Johnson, a Progressive in public policy thinking, believed that public transit was a service which should operated by the city at the lowest possible cost to passengers.

At the time Ohio law did not authorize cities to own public transit operations, so in the interim, Johnson and his allies created the Municipal Traction Company. Organized as a holding company, its aim was to lease Cleveland electric railway’s lines and operate them in trust until such time as city ownership became possible. True to his Progressive ideals, Johnson advocated a three-cent fare instead of the five-cents which was then being charged.

Naturally, his point of view alarmed Horace Andrews and John Stanley, the leaders of the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, who were not interested in ceding control of their properties or finding their profits squeezed. But Johnson’s allies had the upper hand. The city could choose not to renew the franchises under which various lines were then being operated. Facing that threat, Cleveland Electric Railway Company reluctantly agreed to lease its lines to a newly created Municipal Traction Company.

The battle, however, was not over. With reduced income, the municipal traction company was unable to meet its workers’ wage demands. to save money routes were revised, much to the riders’ displeasure. a strike followed, but when that had been settled, disgruntled employees conveniently chose not to collect fares from the passengers. Ultimately municipal traction company could not pay its debts, and in 1908 the local streetcar lines went into receivership.

The case was held in the federal district courtroom of Judge Robert W. Tayler. He determined that the street railways belonged to the private company, renamed as Cleveland Railway Company. He also held that the railways operated over streets belonging to the public. His solution was to set up a 25-year franchise for the Cleveland Railway Company, but to make it subject to oversight by a Cleveland Traction commissioner. The commissioner was authorized to determine routes and schedules for the company, but the company was to be entitled to an annual 6% return from its operations. the new organizational scheme thus recognized the interests of both private and public factions. It went into effect on March 2, 1910.

The privately-owned Cleveland Railway Company operated the city transportation system until 1942, when the city of Cleveland established the Cleveland Transit System and purchased the railway’s assets.

Building a union railroad station—another battle

Just as the streetcar industry was critical for transportation within the city, the steam railroad played that same role for transit and commerce between cities. Cleveland was in need of a new passenger railroad depot.

While the traction issue had been settled by a court, the site for a new Cleveland railroad station was to be decided by the voters. It was a contest between a lakefront site at the northern end of the mall and one on Public Square, the former favored by the city’s establishment and the latter by two entrepreneurs on the rise – Oris Paxton and Mantis James Van Sweringen.

In 1903, behind the leadership of mayor Tom Johnson, a Group Plan Commission unveiled a plan which would clear 101 downtown acres. Its centerpiece was a 500-foot wide central mall, stretching from Rockwell Avenue north to the bluff overlooking the lake front railroad tracks. New government buildings would be built along the mall perimeter, giving Cleveland an impressive new civic center, befitting the city’s ever increasing status. Most of the buildings proposed in the Group Plan were built. Plans for a new railroad station, however, languished.

At the time Cleveland had several railroad stations, each serving different railroad companies, but the main Union Depot, at the foot of West Ninth street, was the busiest. It served both the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads. It had been built in 1865, and it was in deplorable shape and filthy from decades of pollution from the steam locomotives that served it. The first site to greet most visitors to the city, it was a civic embarrassment.

Ultimately, the decision about the location of a new station was left to the voters. On January 6, 1919, they went to the polls and by a 3:2 margin selected Public Square as the site for the development. In doing so the voters set into motion the Cleveland Union Terminal Project, which over the next 15 years would significantly alter the city’s skyline and create for Cleveland its most famous landmark. Simultaneously, however, their decision left the long-time civic vision to complete the Mall Plan unfinished. Over the 100-plus years since the Group Plan was first presented, Clevelanders have been vocal in demanding that the basic mall layout not be compromised. That issue has bedeviled plans over the years, and it remains a challenge to the present time.

Voters, politicians, and a subway

The first plan for a downtown subway was the result of the dramatic increase in passengers on the surface lines of the Cleveland railway company. Between 1910 and 1920, annual passenger totals climbed from just over 225,000,000 to nearly 451,000,000. Downtown Cleveland had become the place to shop, not just for inhabitants of the city, but for the entire Northeastern Ohio region. Streetcar traffic and the increasing number of automobiles, which numbered over 40,000 by 1920, were choking the downtown street network.

The Detroit-Superior Bridge (now the Veterans Memorial Bridge) opened in November 1917. It had been designed with two decks, the top one for pedestrians, bicycles, and automobiles, and the lower deck for streetcars. The separate right of way for the streetcars was intended to speed their way across the Cuyahoga River, and suggested to city planners additional transportation advantages that could come from a subway.

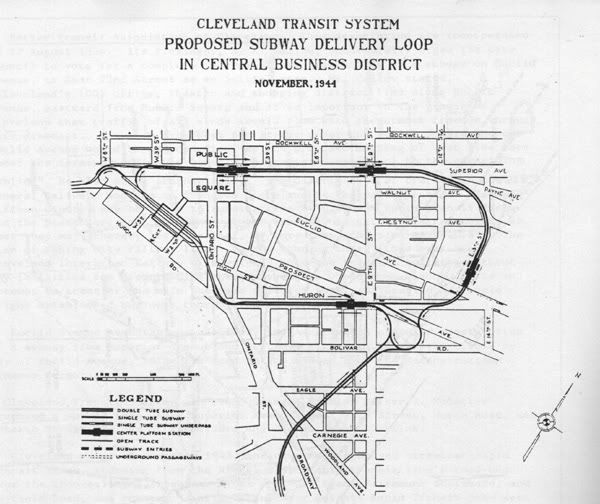

The plan called for modern streetcars operating over the outer portions of existing routes, then joining traffic-segregated rapid transit rights of way, before dropping into a downtown subway loop. It was a plan similar to those then operating in Boston and Philadelphia (and which continue to the present time in those cities). The down- town subway loop would have been built beneath Huron Road, East 13th Street, Superior Avenue, and West Third Street to Cleveland Union Terminal. It would have connected the uptown shopping district (Halle’s and Sterling’s, Bonwit Teller) with the stores clustered near Public Square (Bailey’s, Higbee’s, and May’s).

In 1945 the city of Cleveland hired a Chicago consultant, Deleuw, Cather and Company, to review the modernization plans. Its report held that the city only needed a single rapid transit line, rather than several, but it supported the idea of a downtown subway. Plans for the rapid transit line went forward, and today’s red line, the portion from Windermere to West 117th street (later extended to West 143rd street and later to Cleveland Hopkins International Airport) was the result. It opened in 1955. The subway portion of the plan, for which a $35 million bond issue had been approved by voters in November 1953, was in the planning stages.

Highway improvements were also getting increased attention. In 1940 county voters approved a bond issue to finance the next stages in highway improvements. Automobile registration in the county had skyrocketed to 350,000, a more than eight-fold increase in just 20 years. Motorists faced daily gridlock on the existing street network. Limited access freeways were seen as the answer, and work began on the Willow Freeway (today’s I–77).

In 1944 a comprehensive plan for future freeway development was published. it called for “Outerbelt” freeways, serving the perimeter of Cuyahoga County, as well as radial freeways with downtown as their axis.

Substantial progress of translating this system of limited-access roads, however, did not occur until after 1956 when Congress passed of the Federal-aid Highway act to establish the interstate system. The first portion of a revised highway plan, generally designed along the lines of the 1944 version, was the Innerbelt Freeway. Its first segment opened to traffic in 1959.

The plan for the downtown subway became the focus of heated debate. While its advocates cited the need for a rapid transit system with more than one downtown station, the plan was vigorously opposed by Cuyahoga County engineer Albert Porter. He contended that population was shifting to the suburbs, public transit ridership was falling (by 1959, from its peak in 1946, 250 million riders since its peak in 1946), and that downtown was losing its pre-eminence as a destination. Ultimately, his arguments prevailed, and in December 1959, the county commissioners decided not to issue the subway bonds.

At the same time, taking advantage of the federal support for building the interstate system of Highways, local planners moved forward. Beginning in 1956 with the downtown Innerbelt, the road-building project eventually resulted in 116 miles of super-highway within Cuyahoga County.

Beginning in 1960 Cleveland Transit System officials proposed a series of six new rapid transit lines that would radiate from downtown to all corners of the county. It was their belief such an investment was the only way to mitigate the pull of decentralization. None of these was ever built.

The automobile had become the highest priority in transportation planning, and it would remain in that position right up to the present time.

Regionalization begins to take hold

In 1950, the city of Cleveland reached its all-time peak in population, with 914,808 city dwellers. Cuyahoga County’s population also continued to grow, reaching 1,389,582; the city’s population accounted for 66% of the county total.

But then things began to change. At first the loss of city population was modest. Between 1950 and 1960, Cleveland lost just over 4% of its residents. By 1970 the out migration to the suburbs had accelerated, the city losing another 14% of its citizens, and for the first time more people were living in the suburbs than in the central city. Cuyahoga County’s population had climbed to 1,720,835.

During the 1970s the trend became even more severe. Cleveland lost another 177,057 residents during that decade, and for the first time the county also saw its numbers shrink. Besides the loss in numbers from Cleveland itself, the suburbs had also begun to lost numbers. Altogether, the county’s population fell by 222,435 to a total of 1,498,400.

Not only had the population begun to move ever farther from the mother city, but Cleveland’s strength as an industrial and manufacturing was also being eroded, as plants and jobs moved to the southern states and out of the country as well. These demographic changes translated into a dollar drain, and the city could no longer afford to operate elements of its infrastructure. The response was recognition that the burden of supporting urban life had to be spread more broadly.

One of the first steps towards regionalization came in 1968 with the establishment of the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA). The agency was charged with establishing priorities for future transportation and water quality projects.

Soon came a series of other transfers, responsibility being shifted from the city to county and/or regional bodies. In 1968 the commercial waterfront became the responsibility of the newly established Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority. In 1970 the Metroparks assumed control of the Cleveland Zoo. The Cleveland sewer system was turned over to the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District in 1972. In 1975, the Cleveland Transit System, deeply in debt and bleeding ridership, was turned over to the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority. And then in 1978 the state of Ohio established the Cleveland Lakefront State Park to manage the city’s lakefront park properties.

In the course of a decade the city of Cleveland was able to shed financial responsibility for all of these assets, and turn them over to a countywide authority for their future operation. It was a real start towards regionalization, but that effort seemed to stop at the county’s borders.

In transportation, for example, the new Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority was authorized to serve the broader Northeast Ohio region, but doing so would require adjacent counties seeking the service to support it financially. None of the neighboring counties chose to do so.

The 1980 census revealed a drastic drop in the city’s population, to 573,822. For the first time Cuyahoga County also showed a loss, with some 220,000 fewer residents than just one decade earlier. The steps taken towards regionalization during the 1970s were proving to be only a temporary solution. A broader support network was needed.

It took some time to develop a plan that would advance the regionalization effort. In 2004 the Greater Cleveland Partnership (formerly the Greater Cleveland Growth Association and itself a product of merger among area advocacy and development groups) launched a three-year plan to “mobilize private-sector leadership, expertise and resources to create jobs and leverage investment to improve the economic vitality of the region.” One component of the plan resulted in the major chambers of commerce in the region joining to form Team NEO, a business-development agent for 16 Northeast Ohio counties. Another was the formation of the Cleveland Plus marketing alliance to coordinate a general marketing strategy and program for the region. These programs helped not only to promote the region to the rest of the country, but they also served to raise the consciousness of the local population (about 4,000,000 in the 16-county area) of the importance of working together to advance the region. One manifestation of this local consciousness was the approval by Cuyahoga county voters in November 2009 of a new charter for more effective county government. The resulting vision from these efforts is essentially threefold: 1) sustainable economic development, 2) population stabilization, and 3) quality of life across the region.

These are the 21st-century challenges that now face Northeast Ohio, and a broad consensus has been achieved about them.

NOACA, the agency responsible for local transportation planning, in its Connections 2030: A Framework for the 2030 Transportation System, reflects this consensus. in particular, NOACA has identified revitalization of the region’s urban core as a primary focus. It has also produced a goal to “establish a more balanced transportation system which enhances modal choices by prioritizing goods movement, transit, pedestrian and bicycle travel instead of just single occupancy vehicle movement and highways.”

The first half of the 20th century emphasized improvements in the public transit system. the second half of the century was focused on the automobile. Public policy at the start of the 21st century endorses yet a third vision.

New Challenges for Transportation in Greater Cleveland

Many ideas have been advanced to achieve the goals to achieve the three fold goals for revitalizing Northeast Ohio. as with most ideas of this kind, there are both advocates and critics, not mention a plethora of obstacles that must be faced and surmounted to bring these plans to life. east of them tackle the challenge from a different perspective.

Highway planning

Three highway projects are on the planning frontline in 2010. Two represent a reconstruction of existing highways and the other a return to a long dormant idea.

The most costly of these projects involves the rebuilding of the Innerbelt Freeway, a task made necessary by the deterioration which the fifty-year-old downtown bypass route is experiencing. The project calls for a second bridge to be built across the Cuyahoga Valley. When that project is completed the existing bridge will be completely rebuilt. The project also involves the re-engineering of the lakefront “Dead Man’s” Curve, as well as reducing the number of on/off ramps between the curve and the bridge.

As is typically true of most Cleveland projects, this one has experienced considerable public criticism, centering around bridge design and the impact on downtown venues from fewer access points.

The second highway project involves rebuilding the West Shoreway (also designated as Ohio Route 2). The reconfiguration would cover the highway from Baltic Avenue on the west side to downtown. The plan envisions changing the limited-access, 50-mph freeway into a tree-lined boulevard with a 35-mph speed limit. It would add three entrance/exit points along the route, thus making Edgewater Park and adjacent properties more accessible to the west side neighborhoods that flank the highway. Such an improvement is seen as enhancing the prospects for the continued revitalization of the Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood. The project is seen as contributing to the goal of improved quality of life for city dwellers.

The third project carries the name Opportunity Corridor. It is a 2.75-mile boulevard running from the eastern terminus of interstate 490 at East 55th Street east to East 105th street at the edge of the city’s University Circle medical, educational, and cultural hub. NOACA has given the project a high priority.

The current plan represents a significant reconfiguration of the long-abandoned Clark Freeway which would also have traveled east from East 55th street, but its path would have carried it through Shaker Heights, significantly disrupting both residential and park settings. It was vetoed by the residents of that suburb.

The new routing would have minimal impact upon residential neighborhoods, running through mostly abandoned industrial sites and along the rapid transit right of way that traverses the area. The highway is seen as a significant economic development tool, opening up some 350 empty acres to new industrial construction and the attendant jobs that these would generate. The plan also addresses quality of life issues, making the University Circle attractions more directly accessible from the area’s existing interstate highway system.

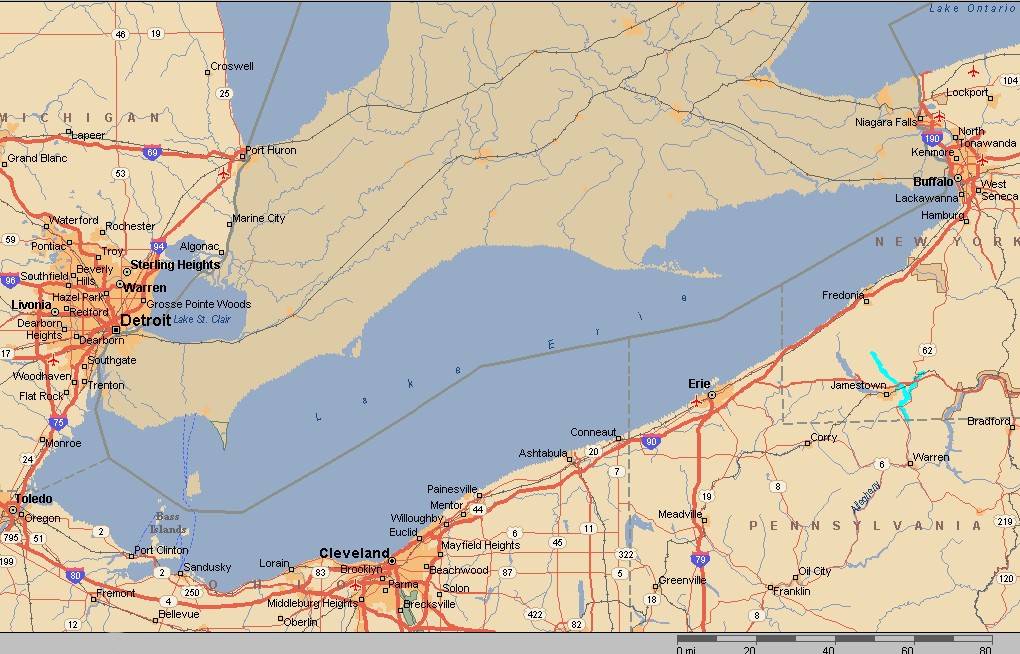

The Port of Cleveland

Cleveland’s very existence is due to its geographic location at the confluence of the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie. Cleveland was founded in an era when water transportation was the primary means for moving freight. The Port of Cleveland has continued to be an important part of the region’s commercial network.

As the regional priorities have changed, however, a growing consensus has emerged that the location of the port, on downtown lake front land, may not be the most promising future use of that area. A 2004 City of Cleveland planning document called for major redevelopment of the downtown waterfront for residential and recreational use.

A preliminary proposal to address this interest suggested relocating the port facilities farther east to a newly created dike area near East 55th Street. The cost of such a move, the time required for its implementation, and changes in personnel on the Port Authority board and its management team, however, spelled the end of active consideration for the idea

Instead, at least in the short term, port officials are looking more closely at underutilized port land west of the Cuyahoga River, and they are pursuing plans to increase the capacity of the port to handle container shipping via Montreal and the St. Lawrence Seaway. Such a development is seen as attractive to international shippers, considering the congested nature of ports on the eastern seaboard. Another aspect of this plan would envision facilities to handle truck traffic ferried across Lake Erie from Canada.

An urgent problem faced by the community is the need to build a new dike to handle dredging from the Cuyahoga River. The current dike at the east end of Burke Lakefront Airport will have reached capacity by 2014, and the port needs to determine a new site for the more than 300,000 cubic yards of sediment removed from the river and harbor each year.

Passenger Railroad Service

Passenger rail service for Clevelanders is limited. As of 2011, Amtrak trains connect Cleveland with Chicago, the Lake Shore Limited and the Capitol Limited. The eastern portion of the Capitol Limited route connects Cleveland to Washington, D.C., and the Lake Shore Limited connects with New York city and Boston.

In 2009, the federal government’s stimulus plan authorized a $400 million plan to connect Cleveland with Columbus and with Cincinnati, via Dayton. The so-called 3C route was warmly greeted by then Governor Ted Strickland, although critics cited limitations to its appeal for travelers. Because the plan would have had passenger trains sharing existing track with freight trains (although some of the route would have been improved by additional passing sidings), the passenger service’s top speed would be limited by existing safety regulations. Critics felt that while rail service would be more comfortable than intercity bus travel, its inferior schedule speed would be a deterrent to broad acceptance.

Newly elected Governor John Kasich rejected the 3C proposal in one of his first acts upon taking office in 2011.

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority has also studied the development of a commuter rail network. In its Transit 2025 document, it offers the possibility of developing rail connections between Cleveland and Painesville, Aurora, Akron, Lorain, Elyria. A rail link beyond Lorain to Sandusky via the existing Nickel Plate corridor has more recently been given a closer look, but any prospects for such a line carry a completion date at least ten years into the future.

Airport Decisions

Cuyahoga County has three airports: Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, and the smaller Burke Lakefront Airport and Cuyahoga County Airport. The question has been rather continuously raised about whether both of the smaller airports are really needed. Burke Airport was built in 1947 on the site of a lakefront garbage burning site. Cuyahoga County Airport opened in 1950 in suburban Richmond Heights.

The two smaller airports serve to siphon smaller private and corporate aircraft from Hopkins, thus relieving congestion there. In light of the fact that neither smaller airport has achieved the promised benefit that was forecast for them, should operations be consolidated at one of them?

If Burke were to be closed, 450 acres of valuable lakefront land would be opened for commercial and residential redevelopment. Its central location, however, in comparison to Cuyahoga’s location 11 miles east of downtown, makes Burke a more appealing to the business traveler.

While planners suggest changes in the current status of the two smaller airports, officials continue efforts to improve the infrastructure and operational features of both facilities. A decision about the future does not appear imminent.

Pondering Past and Present Policy

Past Ponderables

1. The first of the six downtown department stores closed in late 1961. If the downtown circulator subway (rejected by the commissioners in 1959) had been built, would it have allowed downtown to remain a vibrant shopping district, or might it have slowed the decline, or was the eventual death of the Euclid avenue shopping zone inevitable?

2. Would the proposed development of a more extensive rapid transit system, connecting inner and outer ring suburbs to downtown, succeeded in offsetting the pull of outmigration from the city; might it have mitigated the appeal for the suburban office parks that sprang up in the suburbs?

3. Construction of the interstate highway system in the county made cross-county travel much easier for motorists. the highways, however, required a right of way that resulted in the demolition of hundreds of homes in Cleveland and which often severed neighborhoods. to what extent was the highway construction program the cause for accelerating the loss of city population and of increasing urban blight?

Present Ponderables

1. Have such organizations as NOACA, Team NEO, and Cleveland Plus correctly identified the priorities which are most critical to the revitalization of Cleveland and of Northeast Ohio? Are there other priorities that should be added to the list or which should replace the current emphases?

2. Are the projects being proposed as addressing the region’s most compelling needs well chosen to meet the established priorities? are these likely to achieve the goals toward which they are pointed?

3. What data can be summoned to either support or criticize plans for a) highway changes; or b) commuter or intercity railroad development, or c) port relocation, or d) airport consolidation?

From Cleveland Memory/Cleveland State Special Collections. Web exhibits, ebooks and archival collections that explore the manufacturing sector in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio.

Brent Larkin joined The Plain Dealer in 1981 and in 1991 became the director of the newspaper’s opinion pages. In October 2002 Larkin was inducted into The Cleveland Press Club’s Hall of Fame. Larkin retired from The Plain Dealer in May of 2009, but still writes a weekly column for the newspaper’s Sunday Forum section.

Immigration (PDF)

by Elizabeth Sullivan

Cleveland long has been a city of steel and autos, a city that boomed with ore men, oilmen and corporate titans and then busted not long after the oil price shocks of the 1970s helped push steel onto life support. It’s a city whose burning river sparked the cleanup of all the Great Lakes, a place that’s finally willing to spark the reinvention of itself through biotech, high-tech, wind energy, green jobs, and medicine.

But through all these years—even going back to 1796 when Moses Cleaveland and his team of land speculators arrived as descendants of English settlers—it’s also been a city of immigrants and migrants. Immigrants from England, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, from the Ottoman Empire, and Lebanon, from the south, including the great African-American migrations of the early 1900s, from Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Puerto Rico, and Mexico, from the Czech Republic, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Italy, from Albania, the ex-Yugoslavia, Guyana, and Jamaica, from Korea, China, and India, from Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, and South Africa, from scores of other nations, and from a mix of religions, Judaism to Lutheranism, Catholicism to Buddhism.

These continuing waves of new arrivals helped set Cleveland’s cultural tone. They established its first hospitals, houses of worship, and other institutions. They settled neighborhoods that bear their marks to this day in architecture and urban landscapes.

Immigrants stoked the great open hearth furnaces of Cleveland’s steel mills and sewed the fabrics that made the city an early center of the garment industry. They worked the docks and the railroads. They brought a multiethnic flavor to city politics—ward heelers heeling by last name and country of origin—but they also created one of the great, high-octane metropolises. They did that through the sheer audacity of what it means to be an immigrant, to leave the familiar place of home and family to find a new start—and then to work together, organizing sometimes by national origin, by family roots, by religion, by language to help seed the small businesses and family stores that propelled jobs from the factories to the street corners.

At one time, Cleveland was home to so many Slovenians that it was the largest “Slovenian” city in the world, surpassing Ljubljana, capital of present-day Slovenia; to so many Hungarians that it was the second largest “Hungarian” city in the world, after Budapest; and to three times as many Slovaks as lived in Bratislava, now capital of an independent Slovakia but that, in 1910, was a largely Germanic and Hungarian city.

They brought their art and music with them: Following the Hungarian and Slovak factory workers to Cleveland were Roma musicians who for decades made Cleveland the New Orleans of the north, their rousing musicians’ funeral processions and plaintive nightclub Gypsy music part of the stimulating mixture of peoples, cultures, and religions that gave the city its flair.

So, too, the progenitors of Cleveland’s diverse button-box accordion and polka music, with Polish, Italian, Czech, German, and Croatian styles, but whose most important heir was Frankie Yankovic and his Cleveland-style Slovenian polka. Yankovic was the son of Slovenian immigrants who’d met in a West Virginian lumber camp and moved to the Collinwood neighborhood of Cleveland in the early 1900s, reportedly after his father’s bootlegging business came to the attention of West Virginia police. It was in Cleveland that the young Yankovic learned the accordion from one of the boarders his father took in to supplement the family’s income from construction work. The National Cleveland-style Polka Hall of Fame was established in Euclid in 1987, the year after Frankie Yankovic became America’s first recipient of a Grammy for polka music.

So, too, the progenitors of Cleveland’s diverse button-box accordion and polka music, with Polish, Italian, Czech, German, and Croatian styles, but whose most important heir was Frankie Yankovic and his Cleveland-style Slovenian polka. Yankovic was the son of Slovenian immigrants who’d met in a West Virginian lumber camp and moved to the Collinwood neighborhood of Cleveland in the early 1900s, reportedly after his father’s bootlegging business came to the attention of West Virginia police. It was in Cleveland that the young Yankovic learned the accordion from one of the boarders his father took in to supplement the family’s income from construction work. The National Cleveland-style Polka Hall of Fame was established in Euclid in 1987, the year after Frankie Yankovic became America’s first recipient of a Grammy for polka music.

The Cleveland Public Library showed the adaptability that was to make it one of the country’s foremost research libraries by quickly adding foreign-language collections to its offerings, Starting with German, and then Yiddish, Italian, Hebrew, Czech, and Polish by the early 1900s—expanding rapidly into other languages, from Hungarian and Romanian to Vietnamese and Swahili. According to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, the city’s library system was the first in the country to include Belorussian language materials, starting in 1973; by 1995, its foreign-literature offerings, with books in 45 languages, as well as a variety of foreign-language periodicals, tapes, and cassettes, were, according to the online Cleveland Encyclopedia article by Jerzy J. Maciuszko, posted at ech.cwru.edu, the most extensive for a public library in the United States.

The presence of so many diverse peoples and religions, and their connections to home countries, also made Cleveland a bridge to world politics. It was in Cleveland that Czechs and Slovaks came together in 1915 to agree, via the Cleveland Agreement, on a union of what was to become Czechoslovakia. Then there was the rise to leadership positions within Cleveland’s Jewish community of two influential rabbis who were fierce zionists, Rabbi Barnett Robert Brickner of the Anshe Chesed congregation and, especially, Lithuanian-born Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, who led the temple in Cleveland for more than four decades. Their intense advocacy for the state of Israel helped win U.S. and U.N. support for creation of a Jewish homeland.

Later in the 20th century, financial support from some ethnic groups in Cleveland became a factor in nationalist movements back home, from the IRA and the Irish Nationalist cause against the British in Ireland, to the 1991 Croatian independence struggle. The significance of Cleveland contributions drew to Cleveland two Croatians who later became Croatian president, Franjo Tudjman and Stipe Mesic, as well as Gerry Adams and others from Sinn Fein’s top political leadership in Northern Ireland.

Today, as Cleveland tries to reinvent itself as a smarter, savvier, more highly educated, more adaptable 21st-century city, it must not dismiss or overlook the core energy and drive that defines the immigrant experience. Immigrants still are helping to make our neighborhoods tidier, livelier, and more diverse. They are bringing economic focus and jobs. Immigrants—particularly highly educated immigrants, but also entrepreneurial family groups and immigrants who continue to act as a bridge to their home countries for attracting businesses and investors—may be the most overlooked economic drivers, both in Cleveland and the nation, of urban revitalization and future wealth.

Cleveland can do much—and much, much more than it’s doing now—to attract and nurture this sort of immigrant. Indeed, such immigrants already are effecting change in Cleveland. If you look closely, you may find them transforming a neighborhood near you.

History of Immigration in Cleveland

As long as Cleveland was a sleepy backwater, it attracted few immigrants apart from those early settlers, who descended largely from original English colonists.

But the Ohio and Erie Canal, which opened in the early 1830s, made Cleveland the important terminus of an economic lifeline extending deep into the country’s heartland and linking the city into a nationwide water transport network. Helped by industrial innovations from steel barons who pioneered what could be called the Cleveland system of manufacturing, in which factories no longer had to be located right next to mines or other sources of raw materials, but could take advantage of water transport to move heavy cargo and finished goods long distances, Cleveland boomed.

The expansion of the railroads reinforced the city’s manufacturing might, including in chemicals and oil refining—as did the Civil War, with its demands for iron and steel. Cleveland’s population exploded, growing almost 90-fold from 1830 to 1870, the year John D. Rockefeller incorporated his Standard Oil company in Cleveland.

From a tiny hamlet modeled on small New England villages with their central squares, Cleveland had transformed into the nation’s 15th largest metropolis by 1870, with nearly 93,000 residents. And it was still growing.

In 1920, with a population that had ballooned to nearly 800,000, Cleveland was the nation’s 5th largest city. The early decades of the 20th century were the halcyon days of the city’s economic power, nationally and internationally, a time during which immigration success paralleled economic success.

Immigrants were attracted not just by jobs, but by earlier waves of immigrants who brought familiar foods and other cultural attributes with them. Yet immigration was not just a mirror for Cleveland’s power. Immigrants themselves also enhanced the city’s economic prospects through their work ethics, craftsmanship, deep sense of social and religious structure, and other skills.

Many of Cleveland’s earliest hospitals were started by German church groups, including the former German hospital in Fairview Park, now Fairview Park Hospital, and Lutheran Hospital on the near West side. So were its breweries.

Well-educated dissidents from the unsuccessful 1848 revolutions in Europe and their descendants put their distinctive mark on the intellectual life of Cleveland. One such was physicist Albert Abraham Michelson, whose Jewish family emigrated in 1855 from Strelno, Prussia (later Strzelno, Poland), when he was a toddler, settling first in Western mining camps. In 1907, Michelson became the first American to win a Nobel Prize in the sciences, for his physics experiments at Cleveland’s Case School of Applied Science, measuring the speed of light.

The skills of old-world craftsmen can still be seen in the stonemasonry of Lakeview Cemetery monuments, many carved by Italian masters who settled in nearby Murray Hill, and the incredible carved wood, iron, and stone work and murals of the city’s ethnic houses of worship, from the intricately carved imported German white oak installed in the 1890s that decorates the interior of the old St. Stephen’s Church on West 54th street—a church for which German craftsmen used locally available wood and iron in place of traditional stone interiors, according to Cleveland Sacred Landmarks by Cleveland State University researchers—to the elaborate carvings and hand-hewn red oak pews lovingly created by Polish craftsmen for the shrine Church of St. Stanislaus in the little Warsaw section of Slavic Village. Not to mention the massive stone blocks hoisted by Italian immigrant brawn that in the 1950s became St. Rocco’s Church on the West side.

Sadly, some ethnic churches with their hand-carved woodwork, marbles, and distinctive stained glass and murals were closed as part of the 2009–2010 retrenchment by the Cleveland Catholic Diocese, in which 50 Roman Catholic parishes in the diocese were closed or merged because of declining numbers of worshippers. The closures were an especially poignant commentary on the relative loss of population in neighborhoods of Cleveland originally settled by immigrants; affected parishes were home to some of the city’s oldest Catholic churches built by Eastern European immigrants between 1880 and 1930—a period when the owners of Cleveland’s mills actively recruited Czech, Polish, Croatian, and other migrants.

Yet the city’s diverse artistic heritage finds ongoing expression in a variety of ethnic arts displays—from the folk-art, costumery, and ceramics of the Romanian Ethnic Art Museum on the West side, the Hungarian Museum in Tremont, and the Czech and Slovak Bohemian Hall on Broadway to the annual Cleveland Fine Art Expo of African-American and ethnic art. A thousand years of Jewish culture in Europe, largely eradicated by the holocaust, is celebrated not just in the city’s temples, but also in the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Beachwood.

The city’s revitalized cultural gardens along Martin Luther King Jr. Drive from Lake Erie to University Circle now include a restored statue of Marie Curie by Polish sculptor Frank l. Jirouche, an arresting stainless steel bowl-like sculpture entitled “Hearth” that was unveiled in 2008 by Azerbaijani artist Khanlar Gasimov, and, next to it, the local Armenian-American contribution, the 2009 geometric “Alphabet” sculpture by architect Berj Shakarian.

But immigrants to Cleveland didn’t just impact the city’s religious life and its arts and intellectual culture.

Tammany Cleveland

The tight-knit nature of some immigrant groups also translated into influence on city politics, with the Irish in particular adept at turning numbers into political clout. Robert E. McKisson, Cleveland mayor from 1895 to 1898, although himself descended from settlers of probable Scots-Irish derivation who’d arrived in northern Summit County early in the 19th century, ran one of the country’s earliest—albeit, shortest-lived—political machines based upon the tight-knit Irish immigrant community.

Even after that machine unwound at the end of the 19th century, ethnic political power persisted through ward heelers from neighborhoods of immigrants, whether Polish, Italian, Irish, or Hungarian. The ethnic loyalties were reinforced by the tendency of many immigrants to follow in the wake of friends, neighbors, or family, effectively transporting village and kinship loyalties to Northeast Ohio.

Most Irish immigrants to Cleveland, for instance, came from one county in Ireland— Mayo—and many of them were from the even tinier Achill Island off the Mayo coast. In 1995, when Plain Dealer reporter Mike O’Malley asked school children in one classroom on Achill Island to raise their hands if they had family members in Cleveland, almost every child raised a hand. A plaque on the wall of a Catholic church on the island thanked donors to the church’s 1964–1965 restoration, “especially our exiles in Cleveland.”

The tiny hamlet of Aitaneet in the Bekaa Valley of present-day Lebanon exported most of its sons and daughters to just a handful of destinations—Cleveland, Montreal, or Detroit.

Likewise, many of Cleveland’s Italian immigrants traced from a small number of towns in Sicily and the Campania and Abruzzi regions. Gene P. Veronesi in his 1977 book, Italian-Americans and their Communities of Cleveland, cites Josef Barton’s seminal 1975 study of differing patterns of immigration to Cleveland as indicating that half of all Italian immigrants to the city arrived from just 10 villages in Southern Italy. That was in contrast to Romanian and Slovak migration patterns to Cleveland, in which such relationship chains were relatively rare.

For the Irish and Italians and some other immigrant groups, such as Croatians and Slovenians who came from relatively small Balkan enclaves, the propinquity of origin and destination helped solidify political power, and perpetuate ties with the “old country.”

John J. Grabowski of Case Western Reserve University and the Western Reserve Historical Society, the area’s leading expert on immigration and settlement patterns in Cleveland, has charted how these migration chains impacted Cleveland area neighborhoods, for decades drawing waves of related immigrants to certain addresses, intersections, and city areas. These ranged from “Dutch Hill” and “The Angle”—the city’s oldest Irish neighborhood—both on the west side, to the St. Clair (Croatian, Slovenian, and Serbian), Kinsman (Jewish), Cedar Central (African-American), and Buckeye (Hungarian) neighborhoods on the east side.

In Lakewood, the “Bird’s Nest” neighborhood was created more or less as a company neighborhood by the old National Carbon Company (later Union Carbide), which in the 1890s laid out the streets named for birds, as part of a recruitment drive of Slovak factory workers. Some of these settlement patterns persist to this day. The St. Clair neighborhood east of downtown continued to attract Balkan immigrants from Serbia, Albania, Bosnia, and Croatia throughout the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

Although the Buckeye neighborhood near Shaker Square now is largely African-American—four of every five residents—2 percent still listed Hungarian ancestry in the 2000 census.

Politicians with Eastern European roots continue to exercise influence: Joe Cimperman, first elected to Cleveland City Council in 1997, is a first-generation Slovenian, as was former Ohio Governor Frank Lausche decades before him. Lausche became the first Cleveland mayor of Eastern European descent, when he was elected in 1941.

Former Cleveland mayor and seven-term (as of 2010) congressman Dennis Kucinich is a second-generation Croatian, while the politician who unseated Kucinich as Cleveland mayor, George Voinovich, who then became a two-term Ohio governor and two-term U.S. senator, is descended from Slovenes and Ethnic Serbs from Croatia.

Immigration continues from Eastern Europe to this day, notably Germans, Romanians, Russians, Italians, and Poles following co-nationals to Cleveland.

In the early 20th century, area steel mills also began recruiting in the Western Hemisphere, primarily in Mexico.

Large-scale Puerto Rican migration to Cleveland and Lorain began after World War II, when area auto and steel plants such as National Tube Company, later part of U.S. Steel, recruited heavily in the Commonwealth, whose residents have been U.S. citizens since 1917 (many serving in the U.S. Armed Forces in both world wars and in every war since).

As of 2008, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that more than 34,000 people of Puerto Rican heritage or birth lived in Cuyahoga County, making it the 28th largest county for Puerto Rican residence in the United States—and the primary reason the U.S. Justice Department demanded in 2010 that Cuyahoga County begin printing all election ballots in both English and Spanish.

But large blocs of immigrants also have come from the Palestinian territories, Jamaica, Vietnam, Ukraine, China, the Philippines, India, Guatemala, Somalia, West Africa, Bosnia, and Iraq—to mention only some.

The Cuyahoga County Board of Elections began providing Russian and Chinese language speakers in some voting districts. And despite the U.S. Justice Department’s focus on the voting rights of Spanish-speaking voters of Puerto Rican descent, the Cleveland neighborhood with the highest percentage of residents with deficient English skills in the 2000 census was the Little Asia neighborhood of Goodrich/Kirtland Park on the near east side, where Chinese and other East Asian languages are the impediment. That neighborhood ranked first in Cleveland in 2000 both in number of foreign-born residents and in number of Asian immigrants, the bulk from mainland China.

No Welcome Mat for Immigrants

All has not been smooth sailing for new arrivals to Cleveland, even in the years when immigration boomed. Immigrants to Cleveland confronted discrimination in housing, employment, and education, and attempts by some white Protestant groups to acculturate other groups, both linguistically and religiously. Often, immigrants experienced infighting within their own immigrant communities over ideology and religion.

The Cleveland Encyclopedia, prepared for the city’s bicentennial in 1996, says that bilingual education was offered in Cleveland public schools as early as 1870—not for altruistic reasons, but as an attempt to induce the city’s large Germanic population to abandon nationality schools taught only in German and to assimilate to English-language education instead.

Protestants sent “missions” into ethnic neighborhoods while the city’s Catholic diocese, under its first bishop, French-born Louis Amadeus Rappe, resisted in the late 19th-century setting up ethnic parishes—until lobbying of Rome by the city’s Germans and Irish ended the prohibition.

By 1908, The Cleveland Encyclopedia reports, more than half the city’s Roman Catholic parishes were “nationality” parishes, rather than neighborhood ones.

Adding to the diversity were the early 20th-century migrations of African-Americans to Cleveland, seeking the opportunities denied them in a south constricted by Reconstruction and later Jim Crow. This wholesale migration, following the rail lines north, established in Cleveland what scholar Kimberly Phillips called “Alabama North,” in her award-winning 1999 book of that name, describing the impact of this migration chain. It indelibly affected neighborhoods from Central to Mount Pleasant. More than half of all southern blacks in the Great Migration northward in 1916–1918 came to just five cities, Phillips writes—Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and Pittsburgh.

Adding to the diversity were the early 20th-century migrations of African-Americans to Cleveland, seeking the opportunities denied them in a south constricted by Reconstruction and later Jim Crow. This wholesale migration, following the rail lines north, established in Cleveland what scholar Kimberly Phillips called “Alabama North,” in her award-winning 1999 book of that name, describing the impact of this migration chain. It indelibly affected neighborhoods from Central to Mount Pleasant. More than half of all southern blacks in the Great Migration northward in 1916–1918 came to just five cities, Phillips writes—Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and Pittsburgh.

African-Americans brought with them their southern customs, cooking, music, and values, including a focus on the church and family as the center of the community. they also made Cleveland a locus of black intellectual life, ranging from author Charles Chestnutt, born in Cleveland in 1858, to Langston Hughes, who in the early part of the 20th century boarded in a number of homes on the east side of Cleveland, as he worked for his education.

But by 1915, reversing earlier, more liberal trends, black migrants to Cleveland faced a backlash of intense prejudice in finding homes, jobs, and cultural and educational acceptance. unlike the assimilation efforts aimed at most immigrants, African-Americans faced closed doors and extreme segregation, from beaches to neighborhoods, schools, and educational avenues of mobility. The effects of this segregation remain painfully apparent to this day in the many Cleveland neighborhoods that are more than 95 percent African-American.

Cleveland’s ethnic enclaves also boiled with rivalries that reflected conflicts in home countries. These were seen in Cleveland Slovaks’ successful 1902 veto of the Hungarian community’s attempt to build a statue on Public Square honoring Hungarian nationalist Lajos Kossuth—the statue was built at University Circle instead. Slovaks had successfully mobilized against the monument by lobbying many of the Cleveland region’s Slavs, whose countrymen had been absorbed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Immigrant Jews of German origin who favored more liberal tenets and assimilation confronted, sometimes uncomfortably, newer arrivals from Eastern Europe with more conservative religious notions, and deeper social needs.

Serbian Orthodox Christians split down the middle into an anti-Communist church that opposed anything emanating from then-Communist Yugoslavia and those who still looked to the home-country church for guidance. This split was resolved only by the wave of Serbian Nationalism that arose during the 1990s Yugoslav wars.

In the America of the early 21st century, immigration has become a negative word, often paired with the adjective “illegal.”

Yet this attitude obscures the real trends in U.S. immigration, ignores the stabilizing, family-friendly, and entrepreneurial nature of most immigrants, and diminishes the positive impact that immigrants can make, especially in communities such as Philadelphia that have worked hard to attract well-educated, well-heeled immigrants, who can make an immediate economic difference.

Recent studies of immigration trends by think tanks as diverse as the conservative Hoover Institution and Rand Corporation and the liberal Brookings Institution suggest that only in states such as California that are overwhelmed by very poor immigrants with low educational attainment has immigration become a net drain on the economy. One inference from these findings is that a smarter economic strategy would be to do more to erase discrimination and to lift other barriers to productive employment for these poorer immigrants, including a greater investment in education, thereby making them net contributors.

Yet immigration is changing. In many if not most U.S. cities, the studies suggest, a new generation of what might be called new-economy immigrants is expanding economic opportunities for all residents by creating new companies, revitalizing neighborhoods, driving the new innovation economy, and attracting investments from overseas.

So even as the stereotypical view persists that immigrants take jobs from native citizens, immigration is changing fundamentally into a value-added proposition.

The Brookings studies in particular suggest that post-1990 immigration has drawn educated immigrant groups not just to cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, and Indianapolis, which have specific programs to lure them, but also to Cleveland, where the city’s emerging power in biotech and affordable neighborhoods close to Cleveland State University and Case Western Reserve University have attracted clusters of highly-educated immigrant Indians, Chinese, and others.

Immigrants within these clusters then lure other immigrants to provide the food and services they crave. And these new-economy immigrants, initially drawn by educational opportunities, later team to start their own firms, including the next generation of high-tech startups.

In the 2000 census, the Cleveland neighborhood with the highest percentage of foreign-born residents—14.5 percent—was the University Circle area around CWRU, the Cleveland Clinic, and University Hospitals. (the top five non-native nationalities living there were Chinese, Indian, Russian, Japanese, and Thai, in that order.) More than three-quarters of this population had immigrated since 1990, in contrast with the city’s older immigrant neighborhoods, such as south Collinwood, where 41 percent of the foreign-born arrived before 1965.

In marked contrast with their 19th-century counterparts, these new-economy immigrants tend to think globally in how they see their roles, their firms, and their personal opportunities. that’s certainly true of Japan-born, CWRU-educated physicist Hiroyuki Fujita, who in 2006 started Quality Electrodynamics LLC in his CWRU lab, making parts for Magnetic Resonance Imaging machines. Now headquartered in Mayfield Village, QED is one of the Cleveland region’s biotech success stories. Yet Fujita didn’t draw inspiration from the old Cleveland manufacturing system. Instead, as he told Mary Vanac of Cleveland’s Medcity News in a 2010 interview, he drew the model for his firm from one of Japan’s early globalists, the entrepreneur-philanthropist Kazuo Inamori, who in 1959 founded a Kyoto ceramics company that was to become the electronics giant Kyocera.

Brookings studies of the impact of such immigrants suggest that the communities that are best able to attract and retain new-economy migrants will see a huge economic spinoff in job creation and innovation. These impacts can happen organically, but Brookings notes that Philadelphia has greatly accelerated them, using a welcome center to recruit and retain immigrants.

Yet even as Philadelphia and other cities worked hard in recent years to attract immigrants, Cleveland lagged, without the political will and vision to make similar moves, and with Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson late to the table on the immigration issue. Fortunately the Cleveland area’s Jewish community—which helped assimilate tens of thousands of Russian Jews and has successfully used immigrant ties to israel to attract Israeli medical businesses to locate in Cleveland—in mid-2010 stepped forward with a strategic study and plan to establish an International Welcome Center in Cleveland.

At the same time, immigrant Eddy Zai of Pepper Pike was setting up the Cleveland International Fund to take advantage of a U.S. program that offers green cards, a step toward citizenship, to foreign investors who sink substantial sums in depressed parts of the United States. Zai recruited potential Cleveland investors in countries as diverse as England, India, and China. The result: a $20 million initial investment in 2010 in the Flats East Bank project, a critical component of that project’s financing. Zai expected to pull together millions more in immigrant investments for that East Bank redevelopment as well as for health-care opportunities, real estate, and movie-making efforts in Cleveland.

Zai’s personal story of immigrant success may, unfortunately, have been necessary to counteract perceptions overseas that Cleveland is not welcoming to immigrants. That view has gained currency in China, in particular, because of the prominent opposition of Cleveland-area politicians such as Senator Sherrod Brown to recent free-trade deals and aspects of U.S. trade relations with China.

These perceptions may be inaccurate—the Cleveland region relies heavily on exports to support tens of thousands of jobs in steel, metalworking, chemical, appliances, large machinery, and other industries, and Brown says he supports free but fair trade. The city continues to welcome immigrants, with the help of the networks of prior immigrants, who tend to form entrepreneurial as well as political and cultural bonds.

However, such perceptions underscore how critical it is for a metropolis to be seen as a player on the international stage—not simply as a place where the barricades are up.

The truth is that Cleveland is competing successfully in the tech-oriented immigrant bazaar, thanks to its biomed and university anchors and the entrepreneurial dollars that have been attracted by state-supported Third Frontier seed money. But how far it has to go was made clear by a recent book, Immigrant, Inc., by Cleveland authors Richard T. Herman, an immigration lawyer, and Robert L. Smith, a Plain Dealer reporter.

Herman and Smith subtitled their 2010 book Why Immigrant Entrepreneurs Are Driving the New Economy (and how they will save the American worker). The authors’ numbers are striking:

• Immigrants make up 12 percent of the total u.s. population but “nearly half of all scientists and engineers with doctorate degrees.”

• Nearly one-fourth of Silicon Valley startups during the computer boom of 1980–1998 were started by immigrants from India and China.

• Immigrants helped launch an astounding 25 percent of all new technology and engineering firms nationwide from 1995 to 2005. That figure was higher in California (39 percent), new Jersey (38 percent), and Massachusetts (29 percent). In Ohio, it was 14 percent.

• In 2006, noncitizen immigrants were listed as inventors or co-inventors of 24 percent of U.S.-filed international patent applications. That compared with 7 percent in 1998.

Herman and Smith contrast Cleveland City Hall’s closed door to immigration policy with the open door of Philadelphia, which “welcomed 113,000 immigrants between 2000 and 2006,” while Cleveland lost “another 7 percent of its population and became almost entirely native-born.”

Fortunately, the Brookings studies suggest that cities can quickly alter their immigration profile through astute policies.

In this regard, Cleveland, where many pre-1965 immigrants retain ties to the “old country,” has assets that other cities do not. In its most vibrant neighborhoods, the city retains the character of an ethnic mixing pot. And diversity can mean a big payoff in neighborhood revitalization.

Cleveland Council Member Matt Zone, for instance, attributes the recent development successes in the Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood that he represents on the West side—the neighborhood that has seen construction of one of the biggest concentrations of new housing in Cleveland, and the advent of trendy eateries and restored theaters as part of the Gordon Square Arts District—to planners’ efforts to retain economic, racial, and ethnic diversity. A small Italian neighborhood complete with backyard bocce courts exists side-by-side with upscale homes for young professionals. Subsidized housing was included in the planning, and the neighborhood should get a further boost by plans to turn the West Shoreway into a more pedestrian and bike-friendly mall, with easier access to the Lake Erie shorefront.

No major ethnic or racial group dominates in Detroit-Shoreway, with 23 percent of residents listing Hispanic heritage, 18 percent African-American, 13 percent Irish, 12 percent German, and 7 percent Italian in the 2000 census. And the neighborhood continues to attract immigrants—with more than 1,000 foreign-born residents as of 2000, the largest numbers from Romania, Mexico, Italy, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

Immigrants don’t just seed new businesses. They’re also are a key driver of population growth—highly desirable in an advanced industrial nation such as the United States that has a low birth rate, since it helps assure that jobs will be filled by working-age people supporting social programs, even as the native-born population ages. The importance of immigration as a population driver was underscored in 2009 when, in part because of declining immigration tied to the Great Recession, the U.S. birthrate dipped to its lowest level in at least a century, 13.5 births for every 1,000 people.

In 1900, according to the Brookings Institution, Cleveland was the nation’s fifth most important immigrant gateway city, with nearly 33 percent of its population foreign-born.

In 2006, it wasn’t even in the top 10. But that can change. Philadelphia—the country’s third largest immigrant gateway in 1900—initially fell as fast and as hard as Cleveland, to become another rusty former gateway and aging industrial city fallen on tough times. Yet Philadelphia changed that trajectory through policies focused on attracting immigrants to revitalize neighborhoods and seed jobs, doubling its foreign-born population after 1970, with 45 percent growth in the 1990s alone.

Cleveland can do the same—or better, building on assets it already has. It not only can, it must. Immigration isn’t a negative word. It’s a word that spells opportunity, growth, jobs, and the future. It has done that for Cleveland before. It can do so again.

Diane Solov is Program Manager of Better Health Greater Cleveland, a multi-stakeholder alliance dedicated to improving the quality of health care for people in Northeast Ohio with chronic illness. Based at Case Western Reserve University’s Center for Health Care Research and Policy at MetroHealth Medical Center, Solov manages the day-to-day operations of all aspects of the program.

Solov came to MetroHealth in March 2007 following a career in journalism, winning numerous awards and recognition for her work. She spent her last 15 years as a journalist at The Plain Dealer, Cleveland’s daily newspaper, as a medical editor, and previously, as a medical reporter. For nearly a decade, Solov often broke and edited stories about Northeast Ohio’s expansive health care market and national health care issues that affected them and their patients.

Solov earned a B.A. in anthropology from the University of Missouri and completed coursework in the M.A. program at its renowned School of Journalism. She was a 2010 Fellow of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Ladder to Leadership program.

Aggregated healthcare news from the Plain Dealer

Web exhibit at Cleveland State Special Collections about Cleveland’s 50+ year history as a “Mecca” for heart care

In the summer of 2004 a lot of the people who had labored to create Cleveland’s much-touted “comeback” in the 1990s were dismayed—if not exactly shocked—when a new Census Bureau report declared it to be America’s poorest city. Christopher Warren was no exception. Warren started out as a community organizer in Tremont long before Barack Obama gave that career path a patina of ivy league cool and long, long before the words trendy and Tremont became joined at the hip. The Tremont Warren worked in was an aging neighborhood of poor white ethnics, isolated from the rest of Cleveland by geography, crumbling roads and closed bridges.

Then in 1990, newly elected Mayor Michael R. White invited him to join his first Cabinet as Director of Community Development. After years of organizing protests against bankers, downtown developers and political power-brokers, Warren was literally at the table with them.

Then in 1990, newly elected Mayor Michael R. White invited him to join his first Cabinet as Director of Community Development. After years of organizing protests against bankers, downtown developers and political power-brokers, Warren was literally at the table with them.

The decade that followed was a heady time for White, Warren (who eventually became his economic development director) and the City of Cleveland. Blessed with a friendly Republican governor in Columbus (former Cleveland Mayor George Voinovich), a powerful member of the House Appropriations Committee in Washington (Louis B. Stokes, the brother of another former Cleveland mayor), a Democratic president who understood the importance of Ohio’s electoral votes (Bill Clinton) and a willing partner at the Cuyahoga County Board of Commissioners (Tim Hagan), White’s administration marched one big project after another across the finishing line: The Gateway complex of new homes for the Indians and Cavaliers, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and the Great Lakes Science Center, the rebirth of Tower City and a new Cleveland Browns Stadium.

But all that did not reverse decades of middle-class flight. Cleveland’s population dropped during the 1990s , as it had in every decade since 1950, to below 500,000 for the first time since 1900. Because so many of those left behind were poorly educated and lacked the skills needed in the modern workplace, Cleveland became an older and poorer city as it hollowed out. That was the snapshot taken by the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The numbers really should have been no surprise—even at the height of its “comeback,” Cleveland had been always been among the 10 poorest cities, if you were simply looking at the income of those people who actually lived within its city limits.

To Warren, part of the problem was where those limits had been drawn many decades ago. Unlike Columbus, whose seemingly elastic boundaries were a source of endless fascination and frustration to him and many of those with whom he served at City Hall, Cleveland was locked in by suburbs. It encompassed only 77 square miles—barely a third the footprint of Columbus. That meant that when a business told Warren’s economic development department that it needed more land to expand, he often had nothing to show within the city limits except brownfields that would require years of expensive, environmental clean-up. In Columbus, his counterparts would have plenty of options, including open space – greenfields, in the lexicon of development – where a business could build immediately, add payroll and start paying more taxes. Warren took great pride in one modern office park he did manage to develop – Cleveland Enterprise Park, but that was on land that the city happened to own in suburban Highland Hills.

Just imagine, Warren mused one day at lunch, if Cleveland’s boundaries were not the meandering zig-zag that appears on maps today, but squared off like those of most cities. Just imagine if the city limits stretched from the Rocky River on the west to SOM Center Road on the east and from the shores of Lake Erie south to interstate 480.

“I don’t think anybody would be talking about Cleveland as the poorest city in the country then,’’ said Warren, pointing out that neither county nor the metropolitan area had poverty rates above the national averages. “We’d look pretty good.’’

Well, thank you, Tom Johnson.

A century after he left City Hall, Tom Loftin Johnson remains the gold standard against which every Cleveland mayor—and maybe every mayor in America—is measured. Elected in 1901, after making a fortune operating private streetcar systems in Cleveland and other cities, Johnson turned Progressive movement ideals into concrete political action.

He created municipal utilities and public baths, enforced inspection standards for meat and milk, built playgrounds in crowded immigrant neighborhoods, expanded the city’s park system and convinced that city dwellers occasionally needed a dose of bucolic country life, purchased the land in far eastern Cuyahoga County on which Chris Warren would one day locate the back offices of downtown banks. He promoted Daniel Burnham’s Group Plan for public spaces and public buildings downtown. He turned City Hall into a laboratory for innovation and a showcase for how an city could and should be run. Even the great muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens declared Johnson to be “the best mayor of the best-governed city in America.’’

Oh yes. And he also pushed for Home Rule.

For the century before Johnson took office, Ohio law had constricted the power of city governments. The state had a hodge-podge approach to issuing municipal charters, which resulted in wildly inconsistent rules for what individual cities could or could not do. The state also retained the right to override local laws, giving it final say over anything that Cleveland or any other city might decide to do. It even dictated the structure of local government.

This bothered Johnson and his allies on two levels. Their Progressive ideals held that people should have as much say as possible over how they were governed. Thus the idea that officials in faraway Columbus could override the will of Clevelanders was an affront to their notions of democracy. Ohio’s cities, Plain Dealer associate editor Arthur B. Shaw would write in 1916, were “handicapped and humiliated. They were governed by a legislature controlled by rural members’’ – a complaint still heard today.

On a more practical level, Johnson and the many able people he brought to City Hall (his most notable protégés included Newton D. Baker and Dr. Harris Cooley) believed that they were more than capable of running Cleveland without the big brother of state government looking over their shoulders. When it came to the daily work city government, they wanted to be left alone. “Home rule” was the first plank in Johnson’s 1901 platform, but try as he did, he never managed to sell it to Ohio as a whole.

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced Ohio’s 1912 Constitutional Convention to add strong home rule language to the state’s newly amended governing document. It gave cities wide latitude to do almost anything that did not conflict with the general laws of the state and federal governments. With Baker stumping throughout the state, the new amendments were approved by voters that fall.

That task eventually fell to Baker, who was elected mayor in 1911, two years after Johnson had been defeated for re-election and just months after his death. Baker convinced Ohio’s 1912 Constitutional Convention to add strong home rule language to the state’s newly amended governing document. It gave cities wide latitude to do almost anything that did not conflict with the general laws of the state and federal governments. With Baker stumping throughout the state, the new amendments were approved by voters that fall.

The victory freed Baker and his administration to do what they were already doing rather well – govern the city efficiently and innovatively. Baker became chairman of Cleveland’s first Charter Commission and helped draft a document that did away with partisan ballots or labels in municipal elections. It was swiftly ratified by city voters and Baker, initially elected as a Democrat like Johnson, served a second term before heading off to Washington as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of War.

The city he left behind was unquestionably well-governed and booming. Cleveland’s population had mushroomed from 381,000 in 1900, just before Johnson’s election, to 560,000 in 1910 on its way to 797,000 in 1920. By the end of World War I, it was the fifth-largest city in the country. Its steel mills, factories and port pulsated with energy and activity. Immigrants, especially from Eastern Europe, poured in to fill all those jobs. Entrepreneurs and inventors sprouted like weeds in a city that might fairly be called the Silicon Valley of the Industrial Age.

But all that economic and political success, says Cleveland State University urban affairs professor Norman Krumholz, helped set in motion the city’s eventual decline and some of the problems that bedevil it now in the Information Age.

As more and more people moved in to the city and the output of its factories increased, so did the unpleasant by-products of rapid urbanization and industrialization. Neighborhoods became overcrowded. Pollution darkened the skies and befouled the air.

Faced with these obvious quality of life issues, those who could afford to, moved away from the sources of irritation.