League of Women Voters-Cleveland

“The Voter” January 2002

www.teachingcleveland.org

The Ohio Constitution – Is It Time For a Rewrite? From the Plain Dealer 12/17/06

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

AMERICANIZATION. The heavy influx of immigrants into cities such as Cleveland before and after the Civil War tested the belief that America could easily assimilate foreign newcomers. Hector Crevecoeur, an 18th-century French writer, had popularized the image of America as a mix of races and nationalities blending into and forming a new culture. On the other hand, nativists who had organized the Know-Nothing Party before the Civil War feared that the foreign customs and “vices” of non-Anglo-Saxon people would destroy America. Anglo-conformists with a similar concern believed in less drastic solutions to make immigrants shed their foreign customs and assimilate into the Protestant, middle-class American mainstream. The public schools were especially burdened with this task.

One of the primary objectives of the CLEVELAND PUBLIC SCHOOLS since their beginning in 1836 has been the assimilation of foreign-born immigrants into American society. The leaders of the city’s schools before the Civil War were transplanted New Englanders who believed that the public or common school was a panacea for the social and economic ills of American society. They claimed, like educator Horace Mann of Massachusetts, that the compulsory attendance of all children in the public schools would educate children not only in the “three Rs,” but also in the cultural values of Anglo-Saxon America. In 1835 Calvin Stowe, one of the most influential leaders of Ohio’s public-school movement, told teachers that it was essential for America’s national strength that the foreigners who settled on our soil should cease to be Europeans and become Americans. But the public school found that immigrant children needed specialized programs to succeed in the classroom. In Mayflower School, built at the corner of Mayflower (31st St.) and Orange in 1851, the majority of students came from Czech families (see CZECHS), and only 25% of the pupils could speak English by the 1870s. Teachers spent a portion of each day providing special lessons in the English language. In 1870 superintendent ANDREW RICKOFF† and the school board instituted the teaching of German, to successfully enroll the majority of the more than 2,000 children of German parentage (see GERMANS) who had previously attended PRIVATE SCHOOLS that taught subjects in German. Educational leaders in Cleveland before the turn of the century believed that the addition of different nationalities would strengthen Anglo-Saxon America, as long as the newcomers conformed to the dominant culture. The goal of mixing nationalities in the common schools was not endorsed by all immigrant groups in the 19th century. Cleveland’s Irish Catholics followed the advice of Bp. RICHARD GILMOUR†, who condemned the public schools as irreligious and told his congregants that they were Catholics first and citizens second (see CATHOLICS, ROMAN). By 1884 123 parochial schools had enrolled 26,000 pupils (see PAROCHIAL EDUCATION (CATHOLIC)). Nationality churches served over 200,000 people by the turn of the century. Parochial schools of the Catholic diocese that taught foreign languages and customs flourished as Cleveland became the home of newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe. Described as “the new immigrants,” they increased from 43,281 to 115,870 people between 1900-10.

School reformers questioned the effectiveness of the policy of Anglo-conformity in the face of the growing cultural diversity of the student population. Some celebrated the philosophy of the “melting pot,” or the mixing of nationalities together. Brownell School on Prospect Ave. had enrolled, for example, over 30 different nationalities by the turn of the century. SETTLEMENT HOUSES, such as HIRAM HOUSE in the Central-Woodland neighborhood of Eastern European Jews and ITALIANS, provided the city’s first citizenship and vocational-education programs, and became the social-service model for Cleveland’s immigrants. In doing so, the settlements carried forward citizenship programs that had been instituted early in the century by patriotic societies such as the Daughters of the American Revolution. In 1901 Harmon School provided “steamer classes,” language instruction for foreign-born children. Evening schools taught adult immigrants civics and English, to help them pass naturalization exams. Schools also expanded social-welfare programs to meet the needs of immigrant, working-class children and youth. In 1907 a medical dispensary, the first of its kind, opened in LITTLE ITALY. Despite these efforts to reach immigrants, the CLEVELAND FOUNDATION‘s school survey of 1915 criticized the school system for not providing enough steamer classes and other specialized programs: among public school students, over 50% came from homes in which a foreign language was spoken. It was estimated that over 60,000 unnaturalized immigrants lived in Cleveland and that two-thirds of the student population left school before the legally required age of 16 for girls and 15 for boys.

The entrance of America into World War I increased anxiety over the effectiveness of the public schools’ Americanization program in securing the loyalty of foreign-born immigrants and their children. RAYMOND MOLEY†, a political science professor from Western Reserve Univ. (see CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY.), was hired to direct its activities. On 6 April 1917, Mayor HARRY L. DAVIS† appointed the MAYOR’S ADVISORY WAR COMMITTEE, which created a “Committee of the Teaching of English to Foreigners,” with business leader HAROLD T. CLARK† as chair. Renamed the Cleveland Americanization Council, the organization coordinated 68 local groups and worked with state and federal programs. The Board of Education trained language teachers, and the Citizens Bureau at city hall supplied instructors of naturalization. Both programs were offered at schools, factories, libraries, social settlements, churches, and community centers. Naturalization classes enrolled 2,067 students during the fall of 1919. The council launched a citywide publicity campaign, which included posters in different languages and advertisements in 22 nationality newspapers. The ideology of social efficiency, often used with employers, stressed that the Americanization of foreign workers would increase their punctuality, orderliness, and productivity. Moley wrote Lessons in Citizenship, a civics handbook, to help immigrants pass naturalization exams. The War Advisory Committee asked ELEANOR LEDBETTER†, a foreign-language librarian for the CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY (CPL), and other researchers to write a series of sympathetic studies of the city’s nationality cultures and neighborhoods. The library also provided newspapers and books in over 20 different languages to reach the foreign-born. Despite this advocacy of cultural pluralism as the basis for mutual exchange and respect, the bitter controversies and feelings aroused during wartime America caused many Americans to lose faith in public school assimilation.

Superintendent FRANK SPAULDING† and the majority of the school board supported the removal and prosecution of a socialist board member who publicly opposed America’s participation in World War I, under the Espionage Act of 1917. The board also terminated the teaching of German and required a loyalty oath from teachers as part of the wartime campaign for “100% Americanism.” Events surrounding the MAY DAY RIOTS and Red Scare of 1919-20 aroused public anger against foreign immigrants who supported radical or progressive causes. On 1 May 1919, the Socialist party’s march in support of the Russian Revolution on Cleveland’s PUBLIC SQUARE incited a riot and the arrest of 116 demonstrators. Local newspapers quickly pointed out that only 8 of those arrested had been born in the U.S. The city government immediately passed laws to restrict parades and the display of red flags. Newspapers and business, labor, and civic organizations called for the deportation of foreigners not wanting to become Americans. Others called for stronger Americanization programs.

Harold T. Clark asked for the passage of a law to compel young people to attend school until the age of 21, and for the adoption of methods used by the army to teach soldiers English. Allen Burns, former director of the CLEVELAND FOUNDATION‘s survey program, conducted a series of studies to improve Americanization programs for the Carnegie Foundation. Cleveland educators and social workers complained about the postwar financial cuts in citizenship training. The PLAIN DEALER alarmingly reported that the city’s immigrant population contained over 85,000 unnaturalized men, and if their families were counted, the number of unnaturalized foreigners rose to approx. 212,000 out of a total residential population of 796,841. The postwar arrival of millions of Southern and Eastern Europeans created a sense of panic throughout America. Schools were judged incapable of assimilating what were seen as biologically inferior groups of immigrants. In 1924 Congress passed a quota law that drastically reduced the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe to 3% of their prewar level, and in effect banned Asians from coming to America.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, immigrant neighborhoods and organizations responded to the needs of the second generation. Often the American-born and -educated children clashed with the values and customs of their parents and moved from their ethnic neighborhoods. Intermarriage between individuals of the same religious faith but different ethnic background created the triple melting pot among Catholics, Jews, and Protestants (see RELIGION). Ethnic parishes and newspapers began to communicate in English as the second and third generations lost the urgency to speak their mother tongue. LA VOCE DEL POPOLO ITALIANO, an Italian nationality newspaper, advertised in English and urged its readers to naturalize. Some ethnic groups controlled assimilation by modifying and adapting their organizations. The Polish immigrant parish gradually changed, for example, to the hyphenated parish of the Polish-American community, and finally to the American parish of Polish ancestry (see POLES). The nationality parish declined in membership in the central city and became a rarity in the SUBURBS because of restrictive immigration laws and demographic changes. Between 1930-40, Cleveland’s foreign-born population decreased by 51,763, or 22.2%, and dropped to a total of 179,183. The proportion of foreign-born in the city’s total population declined from 30.1% in 1920 to 14.5% in 1950. As the second and third generations became more successful economically and more Americanized, or less dependent on nationality organizations, they moved into what were once Protestant-dominated suburbs after World War II.

Different generations of immigrants continued to search for an identity that balanced both their ethnic heritage and the American environment. A conscious celebration of nationality cultures counteracted American ethnocentrism. Folk festivals, sponsored by the CLEVELAND FOLK ARTS ASSN., nationality holidays, fraternal organizations, the All Nations Festival, and the CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDEN FEDERATION all celebrated immigrant contributions to the city. In 1948 the Mayfield Merchants’ Assn. in LITTLE ITALY sponsored a banquet to honor Miss Florence Graham. Of Irish descent, she had faithfully served and fought discrimination against the city’s Italian-American community since 1908, during her tenure as teacher and principal in the neighborhood’s Murray Hill School. The Intl. Institute of the YOUNG WOMEN’S CHRISTIAN ASSN. (YWCA), organized in 1916, trained older immigrants to work with recent arrivals. The Citizens Bureau, with the support of the Welfare Federation, supplied aid, advice, and naturalization classes. The bureau also cooperated with the citizenship and English classes for foreign-born pupils in the public schools, classes which 130,000 foreign-speaking students had attended by 1929.

Eleanor Ledbetter, in addition to building a foreign-language collection at CPL, compiled a volume of Czech fairytales and a bibliography of Polish literature. HELEN HORVATH†, who had immigrated from Hungary in 1897, began mothers’ clubs and educational programs for foreign newcomers. The public schools asked to incorporate her efforts, and she spoke about immigrant education at many universities. John Dewey, the leading philosopher and proponent of progressive education, praised the work of Verdine Peck Hull, who had pioneered a course in interracial tolerance in the public schools in 1924. He declared that the program’s emphasis on mutual understanding represented true Americanism. In 1973 the city created Senior Ethnic Find, a program to help elderly immigrants use available social services. The Nationalities Services Center (see INTERNATIONAL SERVICES CENTER), created by a merger of the Intl. Institute and the Citizens Bureau in 1954, and the LEAGUE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (est. 1934) helped immigrants displaced by totalitarian regimes and World War II. The Cleveland Immigration & Naturalization Service has helped residents sponsor the immigration of relatives, friends, and refugees from other countries and assisted newcomers in becoming citizens.

With the decline in European immigration after World War I, Cleveland employers looked to the American South as a source of cheap labor. Over 100,000 Appalachians and 200,000 blacks migrated to the Greater Cleveland area in the ensuing years (see AFRICAN AMERICANS). The URBAN LEAGUE OF GREATER CLEVELAND helped blacks find jobs and housing and, assisted by the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP), to fight discrimination. A plethora of black churches, KARAMU HOUSE, and fraternal organizations helped rural black newcomers adjust to the urban environment. In the 1960s, public schools began remedial and special education programs for minorities or others described as culturally disadvantaged. Cleveland’s post-World War II population became even more diverse with the addition of Asians, Russian Jewish refugees (seeJEWS & JUDAISM), and Spanish-speaking people from Puerto Rico and Central or South America, Cuba, and Mexico (see HISPANIC COMMUNITY). Displaced persons from Eastern Europe were the major foreign group in English classes, which enrolled over 2,000 students in the public schools in 1949. The Nationalities Service Center flew 270 Cuban refugees into the city as thousands fled Fidel Castro’s victory in 1959.

In 1965 Congress changed the immigration law. With ethnic origin no longer a factor in admittance to the U.S., preferential treatment was given to people with relatives living in America or occupational skills that America needed and refugees from Communism. People from the Far East and India were allowed to enter in large numbers. By the mid-1970s, almost one-third of America’s immigrants came from Asia. Filipinos (see ), Chinese, KOREANS,VIETNAMESE., and Cambodians swelled the population of cities. In 1975 the greatest proportion of the 400,000 immigrants came from the West Indies and Mexico. New and old organizations developed programs to meet the needs of Cleveland’s changing immigrant population. Cleveland’s Islamic Center (see ISLAMIC CENTER OF CLEVELAND) built a mosque in PARMA to serve the needs of the Arab community. The city’s Vietnamese people opened a Buddhist Temple in Cleveland’s near west side. A refugee resettlement office was started to serve approx. 1,500 Vietnamese as well as Laotian and Cambodian immigrants by providing social, employment, and translating services. Approximately 10,000 Asian Indians, of whom the majority were educated professionals, were dispersed throughout the metropolitan region. Cleveland’s Asian community constructed a new addition to the city’s Nationality Gardens in Rockefeller Park near UNIVERSITY CIRCLE and held an annual festival celebrating the diversity of their cultures. The U.S. State Dept. asked the JEWISH FAMILY SERVICE ASSN. to adapt its methods of resettlement to other groups. JFS helped more than 600 Indo-Chinese as well as 1,500 Russian refugees to resettle locally.

By the 1980s, Cleveland’s Spanish-speaking groups had more than 30,000 members in Cleveland. Already citizens of the U.S., Puerto Rican migrants were the largest group. They were assisted by a variety of civic and fraternal organizations, the Spanish American Committee (see SPANISH AMERICAN COMMITTEE), an official liaison at city hall, and an employment-service bureau. Spanish Catholics established SAN JUAN BAUTISTA on the city’s near west side. The Hispanic community helped their young adults with scholarships and educational or cultural programs through the ESPERANZA, INC., Program and the Julia de Burgos Cultural Center. Fifteen hundred Spanish-speaking students constituted the major group in the “English as a Second Language” program in the Cleveland public schools. Over 100 Vietnamese children were also enrolled in the bilingual course.

The PACE ASSN. (Program for Action by Citizens in Education), organized in 1963, developed a human-relations curriculum and trained teachers to increase multicultural understanding. The public schools also developed curriculum to promote an awareness of the history and contributions of minority groups. To combat prejudice against the city’s newest immigrant groups, the Bilingual and Multicultural Education Program of the Cleveland Public Schools helped foreign newcomers learn English and to celebrate their cultural backgrounds. In 1981 it started an annual conference to promote multicultural education as part of the curriculum of the public schools. The program helps students live in a pluralistic world by fostering an appreciation and respect for people of different backgrounds.

Historically, the reaction of Clevelanders to immigrants and migrants has paralleled that of the country in general. Important differences between and among nationality groups have shaped their responses to the culture of the host country. “Birds of Passage,” immigrants who came to America to earn as much money as quickly as possible before returning home, had little interest in becoming citizens or in being Americanized. Programs to assimilate immigrants depended heavily on the immigrants’ reasons for coming to America, as well as the public’s attitudes toward newcomers. When the economy of the city was expanding and in need of cheap labor, immigrants were seen as a vital part of the labor force and capable of becoming American. When the economy slumped in the 1890s and 1930s, or when the public became inflamed over patriotic unity, as occurred in the post-World War I and VIETNAM WAR eras, immigrants were viewed as threats to social harmony and incapable of assimilating. Native-born fears about new immigrants revealed a deep insecurity about American social life and were connected directly to cycles of economic growth and decline. Resentment against the racial backgrounds and illegal entry of foreign newcomers, job losses, and the rising cost of social-welfare and educational services also increased in the 1980s, as approx. 9 million immigrants arrived in America. The total surpassed all previous decades in American history.

Since the 1970s, the American public has seen the rise of a “new ethnic consciousness,” a movement celebrated in Michael Novak’s The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics. Novak believes that millions of ethnics who tried to become Americanized according to the norms of the dominant culture were delighted to find that they no longer had to pay that price. Ethnic pride in cultural differences provided not only a stronger sense of community for immigrant groups, but also an antidote to an age in which modern systems of communication and commerce emphasized the greatest common denominators for a mass audience of supposedly like-minded individuals. This new attitude of cultural pluralism was quickly manifested in cities such as Cleveland. During the 1970s and 1980s, a series of programs began, including the Greater Cleveland Ethnographic Museum, Peoples & Cultures, the WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY‘s Cleveland Regional Ethnic Archives Program, the Public Library’s Cleveland Heritage Program, and CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE‘s Community Studies Program and Oral History Center, that reflected this change in American attitudes. They continued the celebration of regional cultural vitality begun by people such as Eleanor Ledbetter and Helen Horvath, who created a sympathetic understanding of immigrants as the basis for the Americanization of Cleveland.

Edward M. Miggins

Cuyahoga Community College

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY, the third largest research library in the United States, has provided free public access to books and information since 1869. A school district library, it is governed by a seven-member Board of Trustees appointed for seven-year terms by the Cleveland Board of Education.

Although earlier library service had been offered through the Cleveland Municipal School District’s CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL, the present library system opened for business on February 17, 1869 in rented quarters located in the Harrington Block on the southwest corner of PUBLIC SQUARE. Luther M. Oviatt was the first librarian.

The Cleveland Public Library’s innovative, service-oriented philosophy was established by the third and fourth librarians, WILLIAM HOWARD BRETT† and LINDA ANNE EASTMAN†, with the support of long-time Library Board president, lawyer JOHN G. WHITE†. Beginning with Brett, the library worked to bring books to the entire community. It offered open access to bookstacks, services to children and youth, extension work in neighborhood branches and school libraries, and library stations in businesses, factories, and hospitals. Through Brett’s persuasion, Andrew Carnegie donated $590,000 for the construction of 15 branch libraries. Service to the blind began in 1903 with a collection of books in Braille. Specialized reference services to business were developed, leading to the establishment of the Business Information Bureau under ROSE VORMELKER† in 1926.

The Main Library occupied several downtown locations prior to the opening of its landmark building at 325 Superior on May 6, 1925. Bond issues financed the building in 1912 and 1921. Cleveland architects WALKER AND WEEKS were selected in a national competition for the Library, which was to conform to the design of the other civic buildings in Daniel Burnham’s group plan for the MALL.

During the Depression, the Library set all-time attendance records with intensive use of all its resources by Cleveland’s unemployed population. The continuous growth of the Main Library reference and research collections filled the building by the late 1940s. In an effort to alleviate space problems, in 1959 the trustees acquired the adjacent PLAIN DEALER building to house the Business and Science Departments. The area between the two buildings, named Eastman Park in 1937 in honor of Linda A. Eastman, was landscaped as an outdoor reading garden under the leadership of board president Marjorie Jamison in 1960.

By the late 1970s, library use had declined and revenues from the state intangibles tax were no longer sufficient to support the extensive network of neighborhood branches. Branch buildings and their collections deteriorated. In 1974 ERVIN J. GAINES† was appointed the eleventh director; he began a reorganization and revitalization of the Library system. Additional funding was secured through a successful city tax levy in 1975, which supported a $20 million building program to upgrade the branches. Eighteen new or remodeled facilities with attractive new book collections opened.

Gaines oversaw the installation of a computerized on-line bibliographic database to replace the card catalog in 1981. Internal systems and procedures were streamlined and an automated circulation system was introduced. This technology was made available to other local libraries. Cleveland Heights-University Heights was the first to join the CLEVNET system. By 2004 more than 31 libraries from nine Ohio counties, as well as 28 Cuyahoga County Public Libraries were members of the network.

Gaines deferred a major renovation of the Main Library building in favor of the branches, but by the late 1980s the physical deterioration of the older Plain Dealer building placed the collections that it housed at risk. In Sept. 1986, Marilyn Gell Mason was named director and immediately began to plan for a complete modernization of the Main Library complex. In 1991 a $90 million bond issue was approved by Cleveland voters for the renovation of the Walker and Weeks building and for the construction of a new annex to be called the East Wing. In an international architectural competition, the New York firm of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer was selected to design the replacement for the Business and Science building. The former Plain Dealer structure was demolished in May and June of 1994. The completed Louis Stokes Wing, named in honor of Ohio’s first African-American U.S. Congressperson, was dedicated on April 12, 1997, and included 11 floors totalling 267,000 square feet and more than 30 miles of book shelves for a capacity of 1.3 million books.

Director Mason accelerated the library’s technological innovations with the introduction in 1988 of remote access to the library’s catalog through the Cleveland Public Electronic Library from personal computers in homes and offices.

After 12 years, Mason left her post in 1999. Andrew A. Venable, Jr., who had served as deputy director under Mason for three years, became director in June of the same year. Venable remained committed to technology, making the Cleveland Public Library a national leader in web-based services. In addition to on-line resources such as KnowItNow24X7 and Seniors Connect, the institution was the first public library in the United States to offer eBooks, which are electronic books that can be downloaded on to a laptop or PDA for a set period of time. Venable also remained committed to giving people access to the printed word; in 2001, after a 15-year hiatus, the Library re-launched mobile services with a new, high-tech, handicapped accessible mobile library unit. By 2004, the Mobile Library served 43 different locations, including The City Mission, Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital for Rehabilitation, Karamu House, and the Miles Avenue YMCA after-school program.

Cramer, C. H. Open Shelves and Open Minds: A History of the Cleveland Public Library (1972).

Wood, James M. One Hundred and Twenty-Five, 1869-1994: A Celebration of the Cleveland Public Library (1994).

Cleveland Public Library. Annual Reports (2001, 2002, 2003)

www.cpl.org

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

REGIONAL GOVERNMENT. The regional government movement was an effort by civic reformers to solve by means of a broader-based government metropolitan problems arising from the dispersion of urban populations from central cities to adjacent suburbs. When suburban growth accelerated after WORLD WAR II, reform coalitions proposed various governing options, with mixed results. In the 1950s approximately 45 proposals calling for a substantial degree of government integration were put on the ballot. However, supporters failed to make a compelling case for change in areas where diverse political interests had to be accommodated, and less than one in four won acceptance. The most successful efforts to create regional government occurred in smaller, more homogeneous urban areas such as Davidson County (Nashville), Tennessee (1962), and Marion County (Indianapolis), Indiana (1969).

Cleveland was Cuyahoga County’s most populous city by the mid-19th century, and as it continued to grow adjacent communities petitioned for annexation in order to obtain its superior municipal services. As Cleveland’s territorial growth slowed after the turn of the century, a movement was launched by the CITIZENS LEAGUE OF GREATER CLEVELAND to install countywide metropolitan government “while 85% of the area’s population still live in Cleveland and before the problems of urban growth engulf us,” as the League put it in 1917. These reformers believed that the conflicting interests present in the city’s diverse population encouraged political separatism and helped create a corrupt and inefficient government controlled by political bosses. They argued that consolidating numerous jurisdictions into a scientifically managed regional government would improve municipal services, lower taxes, and reconcile the differences within urban society under the aegis of a politically influential middle class. In essence, their proposals were designed to remedy the abuses of democratic government by separating the political process from the administrative function.

Local reformers were unable to achieve their goals by enlarging the city through annexation. The lure of better city services was not an incentive to those prosperous SUBURBS which could afford to provide comparable benefits to their residents and which preferred to distance themselves from the city’s burgeoning immigrant population, machine politics, and the pollution generated by its industries. Cleveland’s good-government groups focused on restructuring CUYAHOGA COUNTY GOVERNMENT either by city-county consolidation or by a federative arrangement whereby county government assumed authority over metropolitan problems, while the city retained its local responsibilities.

Originally, county government in Ohio had been organized as an administrative arm of the state, with three county commissioners exercising only those powers granted to them by the state legislature. To obtain the metropolitan government these progressive reformers envisioned, a state constitutional amendment was needed to increase the authority of these administrative units to a municipal level. The Citizens League submitted such an amendment to the Ohio legislature in 1917, allowing city-county consolidation in counties of more than 100,000 population. It was turned down, but was resubmitted at each biennial session until it became clear that opposition from the rural-dominated legislature required a new approach. Regional advocates then proposed a limited grant of power under a county home-rule charter allowing it to administer municipal functions with metropolitan service areas, establish a county legislature to enact ordinances, and reorganize its administrative structure. Despite backing from civic, commercial and farm organizations, Ohio’s General Assembly still refused to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot, but its backers secured enough signatures on initiative petitions to submit it directly to the voters, who approved it in 1933.

The amendment required four separate majorities to adopt a home rule charter which involved transfer of municipal functions to the county: in the county as a whole, in the largest municipality in the county, in the total county area outside the largest municipality, and in each of a majority of the total number of municipalities and townships in the county. The fourth majority allowed small communities to veto a reform desired by the urban majority. Ostensibly designed to ensure a broad consensus of voters if the central city was to lose any of its municipal functions, this added barrier satisfied Ohio’s rural interests, a majority of whom were unwilling to open the door for a megagovernment on the shores of Lake Erie.

Metropolitan home rule proved to be a durable issue in Cuyahoga County; between 1935 and 1980 voters had 6 opportunities to approve some form of county reorganization. When an elected commission wrote the first Cuyahoga County Home Rule Charter in 1935, the central problem was how much and what kind of authority the county government should have. Fervent reformers within the commission, led by MAYO FESLER†, head of the Citizens League, wanted a strong regional authority and sharply restricted municipal powers. Consequently, they presented a borough plan that was close to city-county consolidation. The proposal crystallized opposition from political realists on the commission who advocated a simple county reorganization which needed approval from Cleveland and a majority of the county’s voters. Any transfer of municipal functions required agreement by the four majorities specified in the constitutional amendment. The moderates prevailed, and a carefully worded county home rule charter was submitted to the voters in 1935, calling for a county reorganization with a 9-man council elected at large which could pass ordinances. The council also appointed a county director, a chief executive officer with the authority to manage the county’s administrative functions and select the department heads, eliminating the need for most of the elected county officials. HAROLD H. BURTON†, chairman of the Charter Commission, and popular Republican candidate for mayor, promoted his candidacy and passage of the home rule charter as a cost-cutting measure. Both Burton and the charter received a substantial majority in Cleveland, and the charter was also approved by a 52.9% majority countywide, supported by the eastern suburbs adjacent to Cleveland and outlying enclaves of wealth such as HUNTING VALLEY and GATES MILLS. Opposition came from voters in the semi-developed communities east of the city, together with all the southern and western municipalities in the county. The countywide majority was sufficient for a simple reorganization, but before the charter could be implemented its validity was contested in the case of Howland v. Krause, which reached the Ohio Supreme Court in 1936. The court ruled that the organization of a 9-man council represented a transfer of authority, and all four majorities were required–effectively nullifying the charter, since 47 of the 59 municipalities outside Cleveland had turned it down.

A county home rule charter continued to be an elusive goal. After World War II the accelerated dispersion of Cleveland’s population to the suburbs encouraged reformers to try again. When the voters overwhelmingly approved the formation of a Home Rule Charter commission in 1949 and again in 1958, it was viewed as another projected improvement in municipal life: an improvement comparable to the construction of a downtown airport; the expansion of Cleveland’s public transportation system; and the creation of integrated freeways. Metropolitan reformers agreed. They were concerned about the growing fragmentation of government service units and decision-making powers in the suburbs and the unequal revenue sources available to them. This made the need for regional government even more urgent. In addition, Cleveland was hard pressed to expand its water and sewage disposal systems to meet suburban demands for service, making those municipal functions prime candidates for regionalization.

Democratic mayors THOMAS BURKE† and Anthony Celebrezze counseled a gradual approach to the reform efforts. The elected charter commissions, however, pursued their own political agenda, unwilling to compromise their views on regional government to suit the city’s ethnic-based government. The commissioners, a coalition of good government groups and politicians from both parties, wrote strong metropolitan charters calling for a wholesale reorganization of Cuyahoga County which would expand its political control. Two key provisions in each charter demonstrated the sweeping changes in authority that would occur. An elected legislature would be chosen either at-large (1950) or in combination with district representatives (1959), isolating ward politics from the governing process and ensuring that the growing suburbs would acquire more influence over regional concerns. The reorganized county would have exclusive authority over all the listed municipal functions with regional service areas and the right to determine compensation due Cleveland for the transfer without its consent (1950), or in conjunction with the Common Pleas Court (1959). If approved, these charters could significantly change the political balance of political power within Cuyahoga County.

Charter advocates, led by the Citizens League and the LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS (LWV) OF CLEVELAND, argued that a streamlined county government with efficient management could act on a score of regional improvements which would benefit the entire area. However, they were unable to articulate the genuine sense of crisis needed for such a change. The majority of voters who had elected the charter commissions approved county home rule in theory; but, faced with specific charters, they found the arguments for county reorganization unconvincing. Cleveland officials successfully appealed to city voters, forecasting that the charters would raise their taxes and “rip up” the city’s assets. Many suburbs also were skeptical, viewing comprehensive metropolitan government as a threat to their municipal independence. As a result, the 1950 and 1959 charters failed to receive a majority. Three more attempts were made by the same good-government groups. An alternate form of county government establishing only a legislature and an elected county administrator was turned down by voters in 1969, 1970, and again in 1980 with opposition from a growing number of AFRICAN AMERICANS, unwilling to dilute their newly acquired political authority by participating in a broader based government. In 1980 only 43.7% approved the change, and there were no further attempts to reorganize Cuyahoga County government. It was clear that a majority of voters cared little about overlapping authorities within the county, they were not persuaded that adding a countywide legislature would produce more efficient management or save money, and most importantly, they wanted to retain their access to and control of local government.

While the future of county home rule was being debated during the postwar period, other means were found to solve regional problems. Cuyahoga County quietly expanded its ability to provide significant services in the fields of public health and welfare by agreeing to take over Cleveland’s City Hospital, Hudson School for Boys, and BLOSSOM HILL SCHOOL FOR GIRLS in 1957. Independent single function districts were established in the 1960s and 1970s to manage municipal services such as water pollution control, tax collection, and mass transit–services that existing local governments were unable or unwilling to undertake. These districts had substantial administrative and fiscal autonomy and were usually governed by policymaking boards or commissions, many of them appointed by elected government officials. Most were funded by federal, state, and county grants or from taxes, and several had multicounty authority. These inconspicuous governments solved many of the area’s problems, but their increasing use also added to the complexity of local governance. Critics maintained that districts, using assets created with public funds, were run by virtually independent professional managers, making decisions outside public scrutiny with no accountability to the electorate. Nevertheless, in Cuyahoga County the limited authority granted to them was an acceptable alternative to comprehensive metropolitan reform–one that did not threaten existing political relationships.

The comprehensive charters written in 1950 and 1959 represented the apogee of the regional government movement in Cleveland. However, the elitist reformers who wrote them eschewed substantive negotiations with the city’s cosmopolitan administrations and failed to appease the political sensibilities of county voters who preferred a “grassroots” pattern of dispersed political power. Carrying on the progressive spirit of the failed CITY MANAGER PLAN, they attempted to impose regional solutions that would significantly change political relationships in the area–a single-minded approach that constituted a formidable obstacle to any realistic metropolitan integration.

Mary B. Stavish

Case Western Reserve University

Agriculture from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

AGRICULTURE. The first settlers in Cuyahoga County followed the usual pioneer routine. They made clearances, planted corn, buckwheat, and rye, fenced in garden patches, and kept oxen, cows, and swine. When the soil had been “tamed” by other crops, they sowed wheat. They carried on their activities in spite of malaria, the ravaging of crops by multitudes of squirrels, and attacks on their livestock by wolves. Many were really professional land clearers who, after a few years, moved on to repeat the farm-making process elsewhere. The remainder, like the incomers who bought partially cleared holdings, became “regular farmers.”

The first settlers in a community under clearance had the advantage of a “newcomers’ market” because later immigrants often had few or no livestock and before long exhausted the food supplies they brought with them, so that they had to buy locally. In parts of Cuyahoga County, the newcomers’ market lasted until ca. 1810. During the WAR OF 1812 Cleveland became an accumulating point for army supplies, and after the war, Cuyahoga County shared the general agricultural depression afflicting the western country.

The depression continued until 1825, when the opening of the Erie Canal allowed shipments of wheat to markets in the east. Later, when the OHIO AND ERIE CANAL opened, there was a ready demand in the adjacent territory for wheat and other farm products, and Cleveland changed from a village to a bustling urban center. At the same time, Cuyahoga County became a region of old cleared farms where most of the occupants engaged in a mixed agriculture, relying on an income from the sale of wheat, wool, and cattle.

The most important local farm specialization was dairying; butter was manufactured for sale to peddlers and storekeepers, but cheese was also made on some farms in Cuyahoga County from the early 1830s. While the county was much less important in cheesemaking than the Western Reserve counties to the east, its output of butter and cheese together in 1839 was valued at $96,083. In 1859 the county’s production of butter was put at 1,162,665 pounds and of cheese at 1,433,727 pounds. During the 1840s, many farmers just outside Cleveland delivered milk to urban residents–some sold at a market or by peddling through the streets, others to milkmen with routes. The Western Reserve dairy farmers bought their cows from drovers in the spring and sold them off in the fall, congratulating themselves on their good judgment when they found a few good milkers among the nondescripts.

A second type of specialization was the commercial growing of orchard fruits by farmers along Lake Erie. By mid-century the fruit, mainly cherries and peaches, was shipped by boat and rail to eastern and western markets. The value of the orchard output in the county in 1839 was placed at $18,179, and in 1859 at $67,437. During the 1840s, grapes were grown in Cleveland and the northernmost townships, primarily as a garden crop, and by 1855 there were about 200 acres of vineyards near EUCLID. There was only a small production of wine; most of the crop was sent by rail as table grapes to eastern and midwestern cities.

A third specialization was market gardening, which involved growing a variety of vegetables, plus strawberries and other small fruits. Limited to the thinly populated parts of Cleveland and its environs, it was carried on almost exclusively by European immigrants and their families, as native-born Americans had no relish for the incessant spading, hoeing, and weeding required. The value of production in 1839 was given as $4,554 (which was probably understated), and in 1859 as $61,192.

In general, Cuyahoga County farmers prospered during the 3 decades preceding the Civil War, and consequently they were able to improve their buildings and buy new types of implements as they became available. Like other Ohio counties, Cuyahoga in the pre-Civil War era had agricultural societies. The first society, organized in 1823, held a few fairs or “cattle shows” but attracted little general support among farmers, disappearing about the 1830s. A second short-lived society was organized in 1834; a third came into being in 1839, held fairs from 1839-41, then suspended operations in 1842. The fourth, established in 1846 under a new state law that provided for a subsidy from the county treasury, was successful mostly because it featured horse trotting at its fairs. This society is still (1995) in existence, but its fairs have long since ceased to be essentially agricultural and have become primarily community homecomings.

In the half-century or so after the Civil War, Cuyahoga County farming became more specialized as increasing urban demand led to a considerable expansion in dairy buttermaking. Dairy cheesemaking was superseded by the factory system, introduced ca. 1863. In 1875 there were 16 of the new factories in operation, and in 1880 about 20, all of which made butter as a sideline. Those west of the CUYAHOGA RIVER were operated by proprietors (“Cheese kings”), and those east of it by cooperatives. The most significant development, however, was the supplying of milk to the Cleveland market, which began in 1868 when the first milk train began operating into Cleveland from Willoughby in Lake County. Originally, passenger trains took on milk cans as an express item at a special rate, but later they might be local freights running on a schedule. As the railroads carried milk cans at a flat rate, the milk suppliers near the city were at a disadvantage, compared to remoter farmers with cheaper land where new dairying country developed ribbon-fashion along the railroads. With dependable transportation available, some dairymen engaged in “winter dairying” (i.e., year-round production), which introduced silage to feed the milking cows through the winter. Although the first silo in Ohio was built at NEWBURGH in 1880, there were few others in Cuyahoga County till after the famous Silo Convention at Cleveland in 1889, when silo construction flourished. By the mid-1890s, Cuyahoga reputedly had more silos than any other Ohio county.

As soon as the milk-train system was established, dairymen ceased to sell milk directly to consumers but marketed it through middlemen in the city, some of whom established depots near the stations for buying and shipping the product. In a subsequent variation, they set up “creameries”–skimming stations with machinery to separate cream from milk. As the milk depots and creameries operated throughout the year and paid better for their supplies than did the cheese factories, the factories began to shut down or sold their facilities to their rivals; by the mid-1890s none remained in the county.

Farmers involved in the milk industry found that the returns were regular and dependable; however, the economic security they gained was offset by an erosion of their independence. They had to comply with the increasingly strict regulations of the CLEVELAND BOARD OF HEALTH, and to be competitive with other suppliers; they had to replace their ordinary cows with those of popular dairy breeds. When they shipped directly to dealers, they had to adjust their workday to the milk-train schedules, which were usually arranged so that milk would arrive in the city by 8 A.M. Perhaps worst of all, they were disposing of a perishable product to buyers who were interested in keeping prices low and who found ways of having the suppliers assume all the hazards of the market.

In response to the unsatisfactory dealer-farmer relationship, some suppliers in the Cleveland milkshed organized the Northern Ohio Milk Producers’ Assn. in 1901 to establish a fair price for milk. Although the group had some success in public relations, its members tended to make individual contracts with dealers whenever it was to their advantage to do so. However, when the Cleveland milk dealers refused to raise prices to reflect the increasing costs of labor and feed in 1916, the association suddenly revived and provided leadership in a short strike, culminating in a settlement which recognized the association as a contracting agent. Soon it began to function as the Ohio Farmers’ Cooperative Milk Co., one of several such organizations in Ohio.

After the Civil War, commercial orchard production declined; cherries, peaches, pears, and plums became uncertain crops because of insect and fungus problems, and many of the orchardists turned wholly or partially to viticulture. By 1890 there were 5,000 acres of vineyards in the county, stretching somewhat intermittently from the Lake County line westward to the market gardens on the outskirts of Cleveland, with a smaller development west of the city. At least during the 1870s, more table grapes were being shipped from COLLAMER(southwest of Euclid) than from any other railroad station in the county; its only near rival was Dover (now WESTLAKE). Grape production in the county reached its maximum in 1899 at 11,591 tons, declining to 3,753 tons in 1919.

Vegetable growing also expanded after the Civil War. Potatoes, always important for farm consumption, developed commercial significance–partly because of market availability. The crop also fit into whatever rotation was being used, left the soil in good tilth, and did not demand excessive labor when farmers bought the available planters, sprayers, and diggers. Although in 1909 Cuyahoga was the leading potato producing county in Ohio, with 1,141,469 bushels, the industry fell off rapidly, with 1919 production only 35.4% of what it had been 10 years before. The decline was attributable to the increasing prevalence of fungus diseases and to soil depletion. Continued lack of profitability in later years reduced its commercial production further.

The market-garden specialty (now usually called truck farming) grew in the Cleveland area in proportion to the increasing population. Of particular importance was the forcing industry, the growing of vegetables under glass for the out-of-season market. In 1900 truck growers had about 21 acres in hotbeds or cold frames and 4 acres in greenhouses, the latter concentrated in the Brooklyn area.

Cuyahoga County agriculture in the years after World War I was in some respects simply part of the national pattern, with a general increase in mechanization. Fundamentally, however, the course of its development was determined by the continued expansion of metropolitan Cleveland. The table shows the decline in farmland acreage and the dwindling number of farms from 1900 on. The reversion to farmland in the 1930s was attributable to the fact that many failed real estate promotions were sold or rented to farmers.

Concurrently, there was a change in the concept of what was meant by a farm. Ca. 1920, with the exception of a few “showplaces” belonging to wealthy Clevelanders, the farms were still operated in conventional fashion by either owner or tenant. Farms of under 10 acres constituted about 10% of the total, but these were usually in intensively cultivated truck crops. With the advent of the automobile, country dwellers could work in the urban sector, and city wage earners could move miles beyond the suburbs. As a result, subdivisions appeared along the roads to the metropolis, with landlords selling off lots on their frontage. Though these parcels were classified as farms, in some cases they served as sites for antique stores, beauty parlors, dog kennels, and other small enterprises, and in many instances the occupants used them primarily as dormitories. Thus, in 1949 (the first year for which such figures are available) there were 136 farms in the county reporting no sales whatever of agricultural produce, and 563 “part-time farms” that reported sales of less than $400. The areas cultivated on the low output farms were so small that there were 404 farms in the county without a tractor, a horse, or a mule.

Changing times made for important developments in the market-milk industry. Beginning in 1917, owners of heavy trucks competed in milk hauling with the railroads and trolley lines, offering the advantages of charging $.04 a can less, picking up the cans from stands at the farmers’ gates, and returning them later in the day. As early as 1919, wherever there were hardtop roads the system of taking cans to rail stations or milk depots was almost a thing of the past. By 1925 some of the trucking lines collecting milk for the Cleveland market reached as far as Ashtabula and Trumbull counties, and during subsequent years, Cuyahoga County milk producers, like other dairymen, suffered from the perennial surplus-milk problem. Perhaps their worst problem was that the rising price of land made dairying uneconomical. The average value of Cuyahoga County farmland per acre (with buildings) was $359 in 1945, $747 in 1950, $1,064 in 1954, and $1,650 in 1959. For these reasons, market-milk production declined sharply after World War II. In 1944, 236 farms sold a total of 9,094,182 lbs. of milk; in 1954, 47 farms sold a total of 4,508,254 lbs.; and in 1959, 10 farms sold a total of 124,190 lbs. In 1964 there were only 100 milk cows reported, on only 7 farms; the industry was gone.

The expansion of the metropolis steadily nibbled away at the fruit-growing areas. From the 1920s on, the only orchard product worth mention was apples, and by 1959 their average value per farm reporting was only about $75. In 1978 there were still orchards on 25 farms, but collectively they comprised only 136 rundown acres. Viticulture also was declining. The production of grapes in the county was 2,849 tons in 1939, and 213 tons in 1978 from the 17 farms still in the business.

While the market-milk and the horticultural industries were disappearing, the truck-farming business continued to expand. Some truck farmers acquired vehicles, enabling them to extend the sphere of market gardening 15 mi. or so into the rural areas, where they often resorted to direct marketing, erecting roadside stands. Even though expenses in the industry were high, operators increased their yields as a consequence of better cultural practices and more mechanization, and often benefited from appreciating land values. As roads improved, they extended their marketing area to include urban centers other than Cleveland, and by selling through cooperative associations they got a larger share of the consumer’s dollar. After World War II, there was a steady decline in open-air vegetable growing as holding after holding was swallowed up by the advance of the metropolis. Truck-farming production, however, continued to increase because many of the open-air growers added to their facilities and entered the forcing business.

The greenhouse sector of truck farming, at least in its concentration in the BROOKLYN (Old Brooklyn) community, was not displaced by urban development. Nevertheless, the rising price of land meant that new facilities tended to be in other areas, especially aroundOLMSTED FALLS. In the mid-1920s Cuyahoga was supposed to have about 160 acres under glass–more than any other American county. The maximum area under glass appears to have been reached ca. 1959, when the census reported 236 acres. Although some of the greenhouses specialized in flowers for the florist trade, most were devoted to lettuce, tomatoes, and cucumbers. By 1982 most of the greenhouse operators were corporations or partnerships; that year there were 16 farms (greenhouse establishments) having sales of over $250,000 each, with an average of $542,813. The county then had 122.5 acres under glass and an output of “nursery and greenhouse products” valued at $11,673,000, or 89.5% of the stated agricultural sales ($13,039,000) of the county.

Until well into the 20th century, living conditions among Cuyahoga County farmers were similar to those in other parts of Ohio. Much of the old isolation had disappeared with the advent of organizations such as the Grange in the 1870s, Farmers’ Institutes in the 1880s, and the introduction of the telephone and free mail delivery. After World War I there was a great improvement in amenities throughout the rural area. In 1930 almost half the farm dwellings had water piped in. Of the 1,589 farms enumerated in the 1950 census, 1,380 had telephones, 1,531 had electricity from power lines, and 1,490 were on hardtop roads. During the 1920s, nearly every farm had an automobile or a pickup truck or both, and practically all had radios, as they would later have televisions. The few one-room schools left in the early 1920s were soon replaced by consolidated ones. There were new organizations, some involved in cooperative marketing, and others education and social, such as the 4-H clubs; many, however, became victims of advancing urbanization.

The steady encroachment of metropolitan Cleveland meant that in 1982 the agricultural census classified only 8,854 acres (13.8 sq. mi.) in the county as “land in farms,” much of it fragmented by limited-access roads, parkways, airports, golf courses, parks, reservoirs, and wasteland. While the agriculture was concentrated in greenhouse operation and other truck farming, there were perhaps still a dozen farms engaged in general husbandry, selling soybeans, shelled corn, melons, sweet corn, and some livestock. Of the 8,854 acres of farmland, 2,364 were in woods. Of the remaining area–classified as “cropland”–336 acres were used only as pasture, and 959 acres were lying idle, which suggested that the land was unprofitable for agricultural purposes or that it was being held for speculation, or both.

Although the 1982 census showed that Cuyahoga County had 193 farms, only 135 had any “harvested cropland.” As had been the pattern since the 1920s, many of the operators engaged in agriculture only part-time or not at all. No doubt some commuted throughout the week to factory or other jobs in the Cleveland or Akron area. All in all, outside the truck-farming sector, Cuyahoga County agriculture in the 1980s had become a marginal operation. As in other old rural complexes surrounding a megalopolis, the prospects were for a gradual further decline.

Robert L. Jones

A POLEMIC ON ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND CULTURAL CONSERVATISM IN CLEVELAND

by Steven Litt

Archibald Willard had no way of knowing it at the time, but when he completed his eight-by-ten foot painting, The Spirit of ’76 for the 1876 Centennial celebration in Philadelphia, he launched what would become the single most famous artistic image produced in Cleveland in the city’s history. Reproduced and copied, celebrated or lampooned in illustrations, cartoons, or parodies by other artists, Willard’s brainchild entered the national mainstream in the 19th century a manner that anticipated Norman Rockwell’s highly popular magazine covers for Saturday Evening Post in the mid 20th century.

Based on memories of a parade witnessed by the artist when he was a child, Willard painted two grizzled men playing the part of veterans of the War of Independence, marching alongside a young boy in a Revolutionary War outfit. While the image is famous, it is less widely known that it originated in Cleveland and arose out of purely commercial impulses. The concept grew out of a commission from publisher James F. Ryder, who realized that the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1876 represented a fantastic opportunity to sell chromolithographs as patriotic souvenirs in Philadelphia, the site of a major national celebration.

In 1875, Ryder recruited Willard, then supporting himself as a carriage painter and a part-time maker of fine-art easel paintings in rural Wellington, Ohio, to move to Cleveland to work on the assignment. Following the success of the lithograph and the original painting, Willard spent the rest of his career creating subsequent versions, one of which now hangs in Cleveland’s City Hall, where an adjacent park at the northwest corner of Lakeside Avenue and East Ninth Street bears the artist’s name.

The success of Willard’s painting, described in detail in the catalog of a 1996 exhibition on the history of Cleveland art at the Cleveland Museum of Art, would appear to be little more than an odd historical footnote. From a larger perspective, however, its prominence is not accidental. It embodies the practical, moneymaking role often assigned to artists in Cleveland, an industrial city in which art has often been closely linked to commerce. The Cleveland Institute of Art, the city’s four-year independent art college, crystallized this utilitarian, business-oriented view of art memorably in its catchy, longtime motto: “Making Art Work.” Embedded in the motto is the notion that Cleveland is a place where no one should be squeamish about exploring connections between creativity and commerce. The motto also conveys a fundamental skepticism about the value of art for art’s sake, or about art as a way to express innovative new ideas. In other words, the motto is unintentionally revealing as a description of less than positive aspects of the city’s artistic and intellectual climate.

Today, public and private philanthropic support for the arts in Cleveland is stronger than ever, and the arts are being called upon to perform a truly big job: to help revive the city’s struggling economy and to make it a more attractive place to live. The question arts supporters and audience members should be asking is whether success in the arts should be evaluated primarily in quantitative economic terms, or according to the more subjective, qualitative benchmarks such as quality, originality, and critical and scholarly esteem. Put in a different way, if economic impact is the primary measure of artistic success and importance, we can all be proud of Archibald Willard and his Spirit of ’76. If, on the other hand, artistic quality is the truer measure of the impact of a city’s cultural contributions, it should be cause for at least mild concern that the author of the most famous artistic image in the city’s history is an obscure 19th-century painter whose work borders on kitsch and whose name is all but forgotten outside Cleveland.

Such concerns are worth discussing, now that the arts are being asked to play a bigger role than ever in the city’s economy. Cleveland’s urban predicament as a shrinking industrial city in a troubled region is widely known. Its population is hovering just over 400,000, roughly sixty percent lower than it was in 1950. The old industrial base is fading rapidly, but new industries, such as health care and biotechnology, are not growing fast enough to reverse decline. Decades-old tensions over race and poverty have caused an exodus of middle-class residents, both black and white. Meanwhile, low-density residential subdivisions in the suburbs consume more and more open land every year, creating a pattern of sprawl without growth.

Within this urban context, the arts, measured by activity levels at major and minor institutions, are certainly working hard. The cultural calendar in Cleveland is packed; venues across the city offer a range and quantity of plays, concerts, exhibitions, and recitals that far exceeds what one might expect for a metropolitan area of Cleveland’s size. Cleveland still compares well in cultural terms with fast-growing cities in states such as Florida, Arizona, Texas, and California. For example, the Cleveland Museum of Art ranks as one of the top 10 institutions of its kind, as measured by endowment wealth. The Cleveland Orchestra is regularly touted as one of the top five in the nation. Playhouse Square, which draws a million visitors a year to Broadway touring shows and local productions, is the second largest unified arts complex in the nation after Lincoln Center in New York. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum steadily attracts a half million visitors a year.

Financial support for the arts in Cleveland is at an all-time high. Evidence of this enthusiastic backing includes the Cleveland Museum of Art’s ongoing $350 million expansion and renovation, described as the largest single cultural project in Ohio history. Other indicators include the 10-year, 1.5 cents per cigarette tax approved by Cuyahoga County voters in 2006 to create a $15 million annual fund to support arts and culture. The fund is the first of its kind in county history. Across the city, developers and planners tout local arts districts as key tools in the fight to preserve struggling neighborhoods. What’s problematic here is that arts funding is based primarily on a utilitarian view of cultural activity as a lifestyle amenity and as a generator of economic activity, not as an expression of the city’s ability to foster original creative thinking of global significance.

Artists and architects in Cleveland rarely attract much notice outside the city. In architecture, local firms rarely win the biggest and most prestigious assignments. Instead, clients prefer to hire prestigious out-of-town firms, which often do less than their best in Cleveland. In painting and sculpture, most of the most famous artists associated with the city have left to pursue their ambitions elsewhere, a telling example of a creative brain drain.

In this context, it’s haunting to consider that Cleveland’s conservative views on the arts have at least until now paralleled the city’s economic decline. This doesn’t necessarily mean that, if Cleveland had been a hotbed of artistic radicalism throughout the past century, it would be in far better economic shape today. But it is true that throughout history, artistic breakthroughs have occurred most often in vibrant and growing cities where innovation and originality in the arts are related to breakthroughs in business, science, and technology. This makes it worth considering whether new and different approaches to the arts could help reverse Cleveland’s decline by making it a place more open to fresh and innovative ideas it has traditionally disregarded or even shunned.

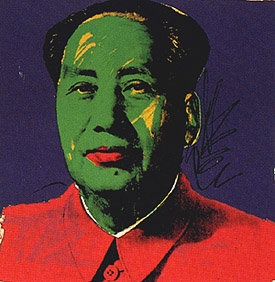

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of Progressive Corp. in Mayfield. Starting in the 1980s, Lewis built one of the largest and most dynamic corporate collections of contemporary art in the country. Curated for more than 20 years by his ex-wife and friend, Toby Lewis, the collection had the explicit goal of dynamic intellectual climate in the workplace as a way to challenge complacency among employees. The Lewises hung multi-colored portraits of Mao Zedong by Andy Warhol in the boardroom. They displayed a racially charged painting by the black Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall outside a cafeteria. Elaborate chandeliers made of dripped wax, by Petah Coyne, graced a stairwell.

No city is entirely homogeneous in its cultural outlook, and this is certainly true of Cleveland. At any one time, the city has had its share of mavericks in art, architecture, and other branches of the visual arts. Perhaps most important among them is Peter B. Lewis, the chairman and former longtime CEO of Progressive Corp. in Mayfield. Starting in the 1980s, Lewis built one of the largest and most dynamic corporate collections of contemporary art in the country. Curated for more than 20 years by his ex-wife and friend, Toby Lewis, the collection had the explicit goal of dynamic intellectual climate in the workplace as a way to challenge complacency among employees. The Lewises hung multi-colored portraits of Mao Zedong by Andy Warhol in the boardroom. They displayed a racially charged painting by the black Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall outside a cafeteria. Elaborate chandeliers made of dripped wax, by Petah Coyne, graced a stairwell.

The idea was to irritate, provoke and remind employees that they lived in a world of constant change, and that they had better grapple with it. The ultimate goal, of course, was to make Progressive a stronger company. Apparently, it worked. While building the collection, Lewis also guided Progressive’s growth from a tiny company with 100 employees in the mid-1960s to its current ranking as the nation’s third largest auto insurer, with 26,000 employees. Lewis also made himself a billionaire in the process. The company’s success certainly derives from as much from Lewis’s leadership and management practices, but cutting-edge art is a strong part of the corporate culture. It could be argued that Lewis’s use of art as a motivational tool is a utilitarian approach to art, but what makes it different from the norm in Cleveland is its profound emphasis on embracing innovation, change, and new ideas.

As the Lewis example shows, a “progressive” approach to culture just might change the city’s traditionally conservative mindset. There’s ample room for similar efforts. These could include rebuilding the region as a center for industrial and product design, based on the rich legacy of creativity left behind by the greatest visual thinker in the city’s history, industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost. Equally important would be a revolution in the city’s architectural and urban design culture, signaled by improvements in the design of buildings, streets, parks, and public places of all kinds. The Cleveland Museum of Art, whose conservative tastes have had a chilling effect on the city’s artistic community, could take a bolder approach. Greater financial support could flow to the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, which has done an outstanding if under-appreciated job of championing the cause of progressive thinking in the visual arts.

THE ROOTS OF CONSERVATISM

Before considering the city’s future, it’s important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of its legacy in the visual arts. Cleveland has certainly played a role in the history of modern and contemporary art and architecture, but not a big one, and it’s important to understand why. The 20th century unleashed a concatenation of new ideas, movements, and artistic breakthroughs across Europe, but emanating primarily in the early decades from Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and other cities. These ideas, ranging from a plethora of art movements such as Cubism and Fauvism, to modernist architecture and design, were introduced to America first in the New York Armory Show of 1913, and the Museum of Modern Art’s first exhibition on modern architecture, in 1932. Following the Depression and World War II, New York replaced Paris as the global center of the art world. Modernist architecture spread across the country, producing vibrant results, especially in Los Angeles and Chicago, but also in New York, Detroit, Philadelphia, and other cities. The same was not as true in Cleveland.

While it’s obvious that Cleveland has had a fairly conservative artistic climate for decades, scholarly work on local art history is fairly thin, which indicates a lack of interest among art historians—a negative comment in and of itself. There exists no large, single-volume historical survey providing a broad overview of local developments in the visual arts in Cleveland and relating them to political, social, and economic trends. Nor does there exist any large study relating the city’s creative output with that of other cities in America and Europe. Such a study would create a clearer understanding of the place Cleveland truly occupies as an artistic and cultural center.

Mostly, the city’s art history is revealed through narrowly focused monographic books on individual artists. The Cleveland Artists Foundation, a small non-profit organization devoted to the visual arts of Northeast Ohio, has published many of these studies.

Though valuable, they don’t provide the bigger picture. The Cleveland Museum of Art attempted a larger overview in 1996 with its exhibition Transformations in Cleveland Art, 1796–1946. Valuable as it was, the exhibition only covered the first 150 years of the city’s artistic history, leaving the rest of the story for a future show. Organized by curators David Steinberg and William H. Robinson, the 1996 exhibition was accompanied by a catalog with an essay that said, “almost nothing has been written about how economic, social, and political events affected the character of Cleveland art.”

Nevertheless, historical and anecdotal information suggests strongly that the city’s cultural conservatism has several roots. One is ethnic heritage. After its initial settlement in the early 19th century, Cleveland’s population grew quickly as waves of immigrants arrived from New England and, later, from countries across Europe. Often, immigrant communities wanted to preserve traditions from their homelands. “Whatever was brought over in the late 19th century stayed that way,” scholar Holly Rarick Witchey, author of The Fine Arts in Cleveland told The Plain Dealer in an interview in 1996.“ When Greeks look for historical folk dances, they come to the U.S., where you are not allowed to innovate. You are preserving the homeland tradition.”

Elite taste also remained conservative throughout the city’s rise to industrial prominence, from 1890 to 1930, and in the decades following. For much of the city’s history, powerful backers of the arts were primarily members of the city’s wealthy and white Anglo-Saxon families. Members of this group included the Severances, the Hannas, and the Mathers. They and others were extremely interested in art and culture, and were extremely generous. Through donations and bequests, they built a large collection of cultural institutions in the early 20th century, starting with the Music School Settlement in 1912, Karamu and the Cleveland Play House in 1915, the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916, the Cleveland Orchestra in 1918, and the Cleveland Institute of Music in 1920.

The cultural largesse of the city’s leading industrial families was motivated by noblesse oblige, a desire to acculturate immigrants newly arrived from poor countries in central and Eastern Europe, and the impulse to compete in terms of prestige with other growing cities. Unlike arts patrons across the industrial Midwest, Cleveland’s wealthy appointed professional managers to guide major institutions, especially the museum and orchestra, to ensure high standards of performance and achievement. Even so, the museum, for example, largely pursued a conservative approach to art history, thereby honoring the tastes and preferences of trustees, who actively discouraged directors and curators from investing in modern and contemporary art.

CONSERVATISM AT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART

Conservatism in culture isn’t necessarily a negative value. In the best sense, it means conserving the finest expressions of the past, maintaining high standards of excellence, and focusing on appreciation of the best of the past, rather than exploring the more risky and unsettled field of contemporary art. In essence, this was the core philosophy of Sherman Lee, the highly influential director of the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1958 to 1983, a period in which the museum rose to international prominence but also gave short shrift to new art.

A serious, sober, deep-voiced authority with an imposing personal presence, Lee was considered during his tenure the opposite of the flamboyant director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Hoving, who first made popular the notion that art museums should cater to a broad public with blockbuster exhibitions and glamorous social events.

When Lee became the third director of the Cleveland museum in 1958, the institution received a massive bequest of $34 million from the estate of industrialist Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., worth roughly $250 million in 2010 dollars. The gift, the single largest in the museum’s history, made it for a time the wealthiest art museum in America, in terms of endowment wealth. Following his mission of conserving the best of the past for the future, Lee used the bequest systematically to build up the museum’s collection of European Old Master paintings, acquiring important works by Francisco Zurbaran, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Nicolas Poussin, Antonio Canova, and Jacques-Louis David. Simultaneously, he built a world-renowned collection of Asian art.

Meanwhile, the museum spent relatively little on modern and contemporary art made after the first decade of the 20th century. The museum assembled a strong collection of Blue, Rose, and Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso, but satisfied itself mainly with works of secondary importance by such important contemporaries as Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, or Jackson Pollock. To this day, the seminal art movements of the 1950s and ’60s, including Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, remain under-represented in the museum’s permanent collection, or are represented by works of secondary quality. Other significant gaps exist throughout the 20th-century collection, which is noticeably weaker than the museum’s highly respected holdings in everything from ancient Greek and Roman art, through Medieval European and Asian art to 19th-century American paintings.

Lee is often pigeonholed as an archenemy of new art, but his story is more complex. He realized in the 1960s and ’70s that prices for modern and contemporary art were rising, and he tried on occasion to persuade trustees to become more open-minded, but he faced heavy opposition. In an oral history interview after his retirement, he recalled a meeting with museum trustees in which he described how a Cubist painting by Picasso had enormously increased in value after the museum bought it. In response, a trustee jokingly shot back: “Sell!” In another instance, Lee recalled how a trustee donated a sculpture by Henri Matisse to the museum after having received the work as a gift from a friend.