From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The link is here

TRANSPORTATION has been of vital importance to Cleveland–a principal factor that explains why the city grew into a major metropolis. Initially, that meant Cleveland’s access to water; a town site along the mouth of the CUYAHOGA RIVER made real sense. Much of the community’s early history involved LAKE TRANSPORTATION, with scores of sailing schooners, brigs, and barks that transported intercity cargos. Eventually, steam-powered vessels appeared, and quickly took over much of the carrying trade. The first steamboat on the Great Lakes, the 330-ton WALK-IN-THE-WATER, made its maiden voyage in 1818; by 1840 more than 60 steamboats served the lakes, and many called at Cleveland’s docks. These vessels were faster, and in most cases could carry bigger payloads, than their wind-driven counterparts. The value of the Great Lakes to Cleveland also increased because of internal improvements to these waterways–lighthouses, deeper harbors and channels and the like–made them more useful to shipping interests. The opening of the Welland Canal between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie in Nov. 1829 enhanced the overall value of the Great Lakes to Cleveland, and construction in the 1850s of the Sault Canal around the falls of the St. Mary’s River at the foot of Lake Superior had an even more pronounced effect. Most of all, the city’s iron and steel industry blossomed. The basic components of these metals–iron ore and limestone–could be transported to sites along the Cuyahoga River by an inexpensive all-water route from the Lake Superior country.

While heavy cargoes dominated Lake Erie commerce, especially after the Civil War, boats also carried people. Daily passenger service between Buffalo and Detroit via Cleveland began in 1830, and the “Forest City” became home port to several of the leading Great Lakes passenger carriers. As late as the first quarter of the 20th century, the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Co. and the CLEVELAND & BUFFALO TRANSIT CO. boomed the merits of pleasure and overnight business trips by water: “Spacious stateroom and parlors combined with the quietness with which the boats are operated ensures refreshing sleep.” But by World War II, the automobile and airplane–the same transportation forms that would greatly reduce intercity rail passenger travel–virtually killed lake passenger service, and the piers at the foot of E. 9th St. became quiet. Modernization also affected freight-carrying vessels on the lake. Great “fresh-water whales”–the long bulk carriers–appeared early in the century and continued the tradition of transporting raw materials to Cleveland plants. By the 1960s these distinctive boats shared water space with oceangoing ships. Completion of the artificial channels and locks of the St. Lawrence Seaway project in 1959 made the latter’s entry possible, and thus Cleveland became an ocean port. The mariner’s map of the world had been altered significantly.

While an evolutionary process was at work on the Great Lakes, Cleveland’s other important water route, the OHIO AND ERIE CANAL, eventually stopped being a transportation artery, but not for several generations after its opening. Even though Cleveland’s population in 1820 totaled only 606, it could still rightfully claim to be a premier lake port. Therefore, state officials wisely selected the community during the early 1820s to be the northern terminus of the projected 308-mi. canal. When completed in 1832, the “Great Ditch” linked Lake Erie at Cleveland with the Ohio River near Portsmouth. A usage pattern somewhat resembling the one seen for lake commerce characterized the Ohio Canal. At first both “hogs and humans” traveled this waterway; the latter boarded specially fitted packets. Admittedly, it was smoother than the ride provided by the various stagecoach lines, but canal travel was extremely slow and unavailable during cold weather or occasional flooding. This means of transportation reached its zenith in the 1840s but declined dramatically with the advent of railroads. Freight, which included wheat, flour, whiskey, pork, salt, limestone, and coal, continued to move by canal long after packets disappeared. Even as late as 1900, the low rates charged by boat owners still attracted bulk cargoes, mostly coal, from east-central Ohio into the ClevelandFLATS. But eventually railroads, in particular the Cleveland Terminal & Valley, conquered the venerable Ohio Canal.

Steam RAILROADS revolutionized Cleveland transportation. By the outbreak of the Civil War, only a dozen years after the arrival of the first steam locomotive, this means of intercity transport was firmly established. The vast majority of people selected railroads for personal travel and to meet their shipping needs. All recognized that water competitors were slow and were universally susceptible to the vagaries of the weather, especially thick winter ice. Furthermore, the railroad offered convenience; businesses tended to choose a railroad rather than a water location. By the post-Civil War era, the flanged wheel had become virtually synonymous with transportation. Yet the Railway Age did not last forever. The first major challenge to the dominance of steam trains came with the introduction of the electric INTERURBANS. Clevelanders in 1895 could brag that they had one of the country’s first intercity traction lines, the Akron, Bedford & Cleveland Railroad. Within a decade, residents had the services of a half-dozen interurban systems that radiated out of the city to the east, south, and west. Interurbans, with their frequent runs, attractive rates, and noticeable cleanliness, siphoned off tens of thousands of potential steam railroad patrons, and captured much of the highly profitable package express and less-than-carload freight business. At times the Cleveland-area steam roads slashed charges or increased trips, but usually they let the interurbans have much of the traffic.

Just as steam railroads showed their vulnerability to interurbans, the latter proved to be even more susceptible to competition. Gasoline-powered vehicles speedily replaced those propelled by electricity. After the dawn of the 20th century, Cleveland emerged as a major center of the AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY, and per capita ownership of the horseless carriage soared. In 1916, for example, Cuyahoga County’s automobile registrations totaled 61,000; 10 years later the figure stood at 211,000. Cleveland’s long-standing ties to the automobile are represented nicely in the career of resident Frank B. Stearns (1878-1955). In 1898 Stearns launched a manufacturing concern, the F. B. STEARNS CO., to build automobiles of his own design and established himself as an important American automobile maker. He also participated in several road races to demonstrate the remarkable potential of this new method of transport. In Jan. 1900 he helped found the Cleveland Automobile Club, the nucleus of the powerful and influential American Automobile Assn. (see OHIO MOTORISTS ASSN.). Services offered by the Cleveland Automobile Club helped expand automobile usage in the area by the 1930s.

Better roads stimulated automobile sales after World War I, and they also did much to encourage expansion of bus and trucking operations. Cleveland’s early intercity bus companies operated relatively short routes; in fact, their system maps closely resembled interurban maps. In 1925, for example, travelers could board vehicles of the Cleveland-Ashtabula-Conneaut Bus Co. on PUBLIC SQUARE for travel to these communities and numerous intermediate points; they might select a run of the Cleveland-Akron-Canton Bus Co., a carrier that followed much of the route of the Northern Ohio Traction & Light Co., or they could opt for buses of the Cleveland-Warren-Youngstown Stage Co., among others. In the 1930s these smaller firms gave way to larger ones. The Cleveland-based Buckeye Stage System served Columbus, Cincinnati, Elyria, and Sandusky; and the Cleveland-based Central Greyhound, associated with Greyhound Lines, operated throughout the eastern Midwest. The remaining smaller operators eventually either folded or merged with Greyhound or its major rival, Continental Trailways. Ultimately, in the 1980s both of these bus giants became one firm.

Although Cleveland never evolved into the region’s leading motor-carrier center, it benefited enormously from the steady growth of this transportation form. But in terms of truck production and truck transport, Cleveland profited greatly from the early innovations of the WHITE MOTOR CORP., which sent 5 experimental trucks in 1902 on a successful round-trip run from New York City to Boston. That company, which for several decades was Cleveland’s largest independent manufacturer in any field, remained in the forefront of truck development and production and also sported a sizable bus-building division. Small trucking concerns, often equipped with White vehicles, appeared before World War I; most provided intracity cartage. But with the triumph of the state’s good-roads movement in the 1920s and early 1930s, and subsequent heavy spending by Congress on federal highways, companies became regional and even interregional in scope.

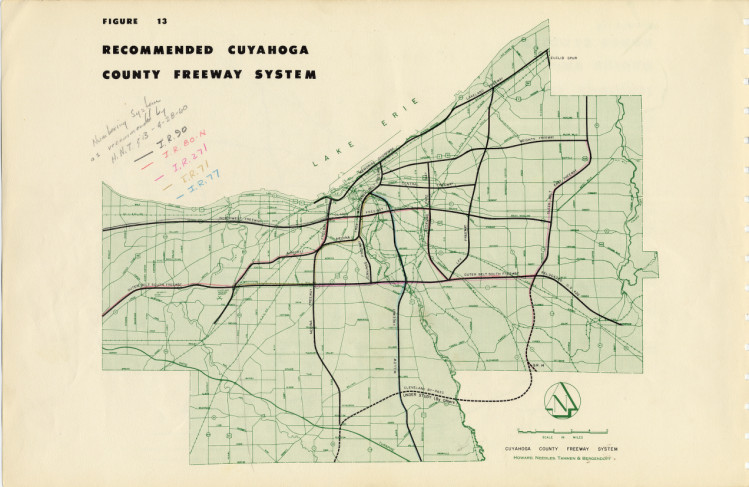

The massive construction of the interstate highway network after 1956, the growing power of the Brotherhood of Teamsters, and other factors gave rise to motor-carrier consolidation. Cleveland was serviced by the industry’s “Big 5”: Roadway, Consolidated Freightways, Pacific Intermountain-Express, Yellow Freight, and McLean Trucking which, with federal deregulation in 1982, became only Roadway, Consolidated Freightways, and Yellow Freight. These companies and their competitors took advantage of the Cleveland market through such improved roadways as the Ohio Turnpike and interstates 71, 77, 90, 271, and 480. The presence of a vigorous motor-carrier enterprise and, to a lesser degree buses, reduced Clevelanders’ dependency on water and rail. Even though rubber-tired vehicles freed the shipper, local businesses here commonly experienced stiff competition from those in other communities who lacked access to a sophisticated Cleveland-type transportation infrastructure. The truck, more than any other transportation form, challenged Cleveland’s claim as the “best location in the nation.”

Clevelanders, though, could smile about their good fortune with AVIATION. Throughout the life of commercial aviation, the city benefited from virtually unequaled air service. Even prior to regularly scheduled passenger operations, Cleveland and a select number of other places enjoyed access to airmail flights. When the public began to travel by air after the mid-1920s, the local terminal never lacked for carriers. In the 1930s a number of companies provided service, but by World War II only 3 dominated: American, Pennsylvania-Central (subsequently Capital and then United) and Central itself. While regulators in the late 1940s opened the city to other strong firms, the number of carriers remained stable. Deregulation in 1978, however, ushered in a plethora of companies, and Cleveland became more of a “hub” operation. United, Cleveland’s largest airline, gradually left the area, and USAir and Continental replaced it as the primary carriers operating out of Hopkins Airport.

Passengers who used CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT after the early 1960s enjoyed easy access to Public Square and other east and west side locations, for Cleveland could claim to be the city with the first rapid-transit line connecting its airport to the downtown area. The Cleveland Transit System (later the GREATER CLEVELAND REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY) was merely the latest operator of Cleveland’s surface rail network. Like most sister cities, Cleveland experienced all types of intracity transportation (see URBAN TRANSPORTATION). The earliest rolling stock to appear on its streets was the horse-drawn omnibus, the 19th century forerunner of the taxi. Omnibus runs started in 1857 and connected the railroad station and lake docks with various public houses. Soon though, the horse (and occasionally the mule) pulled an omnibus-type car on flanged wheels over light rails fixed in the streets. By the Civil War, these “streetcars” rolled on EUCLID AVE.. as far as Erie ( E. 9th) St., turning south on Prospect Ave. and east to the corporation limits. While horse lines flourished in the postwar period, they disappeared in the 1890s. Most communities with horsecars converted to the much more efficient and economical electric trolleys introduced in 1887.

While this transformation likewise occurred in Cleveland, an intermediate phase took place, the cable car phenomenon of the 1880s and early 1890s. Cleveland joined such places as Chicago, Cincinnati, Kansas City, and St. Louis in using cable cars. While inferior overall to the future trolley, the cable car was more desirable than the horsecar, largely because of its greater speed and lower operating cost. In the 1890s Cleveland’s 261,000 citizens rode cars belonging to the Cleveland City Cable Railway from UNION DEPOT up Water (W. 9th) St., and then east on Superior Ave.; or they could change to the Payne Ave. line that continued eastward to Lexington and Hough avenues. In 1893 the CCC became part of MARCUS HANNA†’s WOODLAND AVE. AND WEST SIDE RAILWAY CO., which took the name Cleveland City Railway. The cable lines continued to run throughout the 1890s, even though the faster and more reliable electric cars spread quickly throughout the city. The higher costs of cable operation and the difficulty of expansion led to conversion of the Superior line to trolleys in 1900; the remainder of the system met a similar fate a year later.

Not only did Cleveland’s developing electric streetcars spell doom for the horse and cable cars, but the substantial profit potential and the high capitalization requirements led to the unification of various electric lines in 1893. The result was the creation of 2, at times competing, systems, the CLEVELAND ELECTRIC RAILWAY CO. and the Cleveland City Railway Co. The local press called the former the “Big Consolidated” and the latter the “Little Consolidated,” which common parlance soon shortened to “Big Con” and “Little Con.” The urge to form a private monopoly led to merger of the “Big Con” and “Little Con” in 1903, creating “ConCon.” Although the city finally had its streetcar lines under a single management, consumers wanted a 3-cent fare, not the prevailing charge of 5 cents. Progressive mayor TOM L. JOHNSON† led the battle for a permanent solution to the “streetcar problem”–MUNICIPAL OWNERSHIP. During the Johnson years, reformers repeatedly fought “ConCon” over the fare issue through such consumer-sensitive alternative car lines as the Forest City Railway Co. (1903), Municipal Traction Co. (1906), Low Fare Railway Co. (1906), and Neutral St. Railway Co. (1908). With the establishment of the CLEVELAND RAILWAY CO. in 1910, a prolonged period of reasonable rates ensued, but true public control did not occur until 1942, when the CRC was purchased by the City of Cleveland and became the Cleveland Transit System.

The same technological change that affected the nature of 20th-century intercity travel likewise affected urban transit. “Jitney” buses invaded Cleveland streets before World War I but usually could not compete with the 3-cent trolley fares. Conventional buses joined the Cleveland Railway Co.’s transportation fleet during the 1920s, and eventually the trolley disappeared from Cleveland’s streets; the last streetcar rattled into its car barn from its Madison Ave. run on 24 Jan. 1954. Yet the use of rail transit did not end. The SHAKER HEIGHTS light rail line had since 1914 carried thousands of patrons daily (seeSHAKER HEIGHTS RAPID TRANSIT). Then in 1948, Mayor THOMAS A. BURKE† obtained a commitment from the federal government’s Reconstruction Finance Corp. to buy City of Cleveland revenue bonds to build a crosstown rapid-transit network. After a charter amendment gave an expanded transit board the necessary authority to manage such an operation, the Reconstruction Finance Corp. made the loan for $29.5 million in July 1951. Ground was broken on 4 Feb. 1952, and by the mid-1950s the “rapid” connected Windermere on the east side with W. 117th St. and Madison on the west side, through Terminal Tower on Public Square, and it entered the airport a decade later. In 1975 a revamping of the city’s transit system produced the Regional Transit Authority, which included the Shaker Hts. Rapid; thus the area’s rail and bus operations came under one governing body. During the 1980s, however, the continued exodus of population from the central city has reduced passenger travel on RTA. In 1994 the Gateway project, new home to the CLEVELAND INDIANS and the CLEVELAND CAVALIERS was directly connected with RTA at TOWER CITY CENTER and its use by fans was expected to improve the system’s ridership.

While competition between the various modes had characterized much of Cleveland’s transportation, the complete picture reveals striking examples of coordination and cooperation between transport forms. Obviously, intracity transit operations historically have united local stations and terminals. Trucks and buses, too, have served as vital links in the transportation chain. Less apparent have been the ties between the intracity water, rail, and air carriers. Steam railroads almost from their inception have made connections with lake vessels, especially those that hauled bulk commodities such as coal. In time interurbans offered interchange arrangements with passenger boats. The Northern Ohio Traction Co. established through tariffs for travelers on its system who were bound for Great Lakes cities on the Cleveland & Buffalo or Detroit & Cleveland boats. In the same vein, the NICKEL PLATE ROAD, virtually alone among Cleveland steam roads, promoted steam-electric railroad interchange of freight. A company advertisement in the early 1920s announced proudly: “A physical connection is made with the Nickel Plate Railroad at Cleveland, which permits the movement of Electric Railway Freight Cars into the Nickel Plate Freight terminal for the interchange of both carload and less-than-carload freight.” Like the Nickel Plate, the interurbans were hungry for any type of revenue business, and they commonly established remarkably creative relationships with other types of transport. The most fascinating are 2 traction companies’ dealings with the infant airline industry. In Feb. 1926, officials of the Northern Ohio Traction Co. inaugurated “Freight Aeroplane Service.” Package freight (largely automobile-related) moved by interurban to Cleveland, and then was trucked to the airport for a flight via the “New Ford Air Mail Service” to Detroit. Two years later, on 28 May 1928, the Cleveland & Southwestern claimed to be the first railroad in the nation to offer a through coordinated rail-air service. Interurban passengers purchased a Cleveland-to-Detroit airplane ticket on STOUT AIR SERVICES, INC. from any of 10 stations: Oberlin, Elyria, Wellington, Medina, Wooster, Ashland, Mansfield, Crestline, Galion, or Bucyrus.

Ultimately, the automobile and the motor truck reduced the service given by most of the incumbent forms of public transportation. Since the 1930s, these have been the modes that have altered dramatically the landscape of Cleveland and America; they have truly made the 20th century “the age of the rubber tire.” Cleveland, of course, has continued to benefit from those old 19th-century traffic arteries, Lake Erie boats, and the railroads. Moreover, it has exploited well the advantages of air service. Cleveland remains one of the best-served places in the nation.

H. Roger Grant

Univ. of Akron