Article about Margaret Bourke-White written by Patrick Cox, Ph.D

| Margaret Bourke-White History Making Photojournalist and Social Activist January 2003 |

|

In the beginning, there was Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971). One of the trailblazers in twentieth century photojournalism, Bourke-White played an historic role in media and women’s history. As a woman photojournalist, her reputation rivaled Ida Tarbell, the muckraker who exposed the abuses of Standard Oil, in its impact on modern journalism. Bourke-White became an internationally famous photographer and holds many “firsts” in her portfolio. In addition to her professional contributions, her activism on behalf of the poor and underprivileged throughout the world places her among the foremost humanitarians of the century.

When Bourke-White entered the field of journalism in the 1920’s, few women participated as professional journalists or photographers. A handful of women photographers, Frances Benjamin Johnson, Jessie Tarbox Beals and a few others represented an earlier generation whose photos appeared in newspapers and magazines in the early twentieth century. Although social and vocational roles expanded in the 1920’s, women lived in an era of rigid expectations. Female journalists remained mostly confined to the women’s and society pages of the metropolitan newspapers. As more women entered the profession in the 1920’s and 1930’s, a few doors began to open for women to assume the tasks traditionally taken by male reporters and photographers. Margaret Bourke-White rushed through this door to become a leading figure in the profession.

With the encouragement and guidance of her father, Bourke-White began taking photographs at an early age. She completed college at Cornell and opened her own photographic studio in Cleveland. She ventured into the fiery steel plants where women never ventured. The fiery cauldrons, molten steel, and showers of sparks depicted the industrial might of the nation. The dynamic series of industrial photos in the 1920’s caught the attention of Henry Luce. The well-known publisher hired Bourke-White as the first photographer at Fortune magazine in 1929. Her first assignment in the premier issue provided a physical and a professional challenge – covering the Swift hog processing plant – a site as challenging as the steel mills with its pungent air, bloody working conditions and where one misstep could prove fatal. She went to Russia and provided the first extensive photo series on Soviet Union. Dams, factories, farms, workers, farmers and every day life in Stalin’s communist state came to life for the first time to viewers in the west.

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.

During this period Bourke-White teamed with the popular southern novelist Erskine Caldwell. One of the most widely read authors of the twentieth century, Caldwell is best known for his works God’s Little Acre and Tobacco Road. Working in the poverty-stricken rural areas of the American South, the dynamic team published You Have Seen Their Faces. The pictures of poverty and discrimination in the south rivaled the urban privation photos of Jacob Riis. The gaunt faces revealed the abysmal social and economic conditions of the Depression-era south. Their work received acclaim but was criticized for its bias and exposure of racism in the south. Years after their automobile tour of the south, Caldwell lauded Bourke-White. “She was in charge of everything, manipulating people and telling them where to sit and were to look and what not. She was very adept at being able to direct people,” he said in an interview. Bourke-White and Caldwell were the only journalists in the Soviet Union when the German Army invaded in the summer of 1941. The couple married in 1939 but their relationship ended during World War II.

During World War II, Bourke-White became one of a stalwart group of women correspondents who covered the war from the front lines. Her book They Called It Purple Heart Valley provided a narrative and photographic study of the war in Europe in 1944. She took photos of foot soldiers and generals, victims of the war and its destruction. She slogged through the mud and heat and went everywhere from the front lines to the hospital wards. As she accompanied troops in the Italian campaign, Bourke-White wrote of one encounter. “Right beneath my feet, at the foot of the cliff, was a row of howitzers sending out sporadic darts of flame. Since I was so high up and so far forward, most of our heavies were in back of me, and I could look over the hills from which we had come and see the muzzle flashes of friendly guns, looking as if people were lighting cigarettes all over the landscape.”

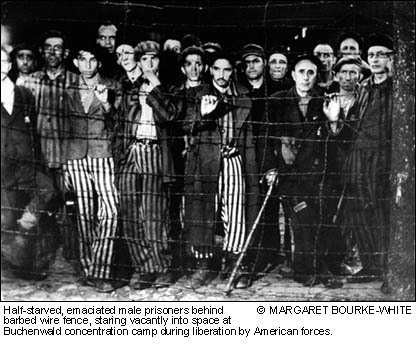

In one of her most difficult tasks, Bourke-White accompanied U.S. troops as they liberated the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1945. With portraits of starving prisoners and dead bodies heaped one upon another, she documented some of the worst horrors of the Nazi regime. Even with government censorship, Bourke-White and her fellow photographers and journalists gave Americans an unprecedented view of the global conflict and the human suffering the war created.

After the war, Bourke-White continued her worldwide photography and focused much of her work on humanitarian issues. She covered Gandhi’s campaign of nonviolence in India and African mine workers and apartheid in South Africa. Carl Mydans of Life said, “Margaret Bourke-White’s social awareness was clear and obvious. All the editors at the magazine were aware of her commitment to social causes.” She joined with other artists to form the American Artists’ Congress that advocated state and public support for the arts and fought discrimination. The FBI began collecting information on her political activity in the 1930’s. During the McCarthy era, she became the subject of scrutiny for her involvement with organizations that promoted civil and political rights. She received criticism by the House Un-American Activities Committee and newspaper columnists for her work on You Have Seen Their Faces and other publications she authored. As she wrote in the Nation magazine on February 19, 1936, “It is my own conviction that defense of the economic needs, as well as their liberty of artistic expression, will inevitably draw them closer to the struggle of the great masses of American people for security and the abundant life which they are more than anxious to earn by productive work.”

Bourke-White developed Parkinson’s disease in 1956. After the diagnosis, she spent six years writing her autobiography. Portrait of Myself was published in 1963. She continued taking photographs and writing until her death in 1971. The most recent study of her career is Vicki Goldberg’s Margaret Bourke-White: a biography. A collection of her works are in The Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White, edited by Sean Callahan. A recent movie entitled “Double Exposure” chronicled her early life and years with Erskine Caldwell. Margaret Bourke-White combined professional skills and a socially responsive philosophy that made her one of the 100 most influential women of twentieth century.

© Patrick Cox, Ph.D

Assistant Director, Center for American History

University of Texas at Austin

pcox@mail.utexas.edu

Dr. Cox authored the biography on the late U.S. Senator Ralph W. Yarborough (D-Texas) published by the University of Texas Press. Ralph W. Yarborough: The People’s Senator, was a finalist in the Western Writers Association and the Robert Kennedy Foundation Book Award for 2002