Confessions of a Reformer by Frederic Clemson Howe (google books)

Frederic Howe, Cleveland reformer, councilman, journalist writing about his favorite mayor, Tom L. Johnson

first page:

www.teachingcleveland.org

Confessions of a Reformer by Frederic Clemson Howe (google books)

Frederic Howe, Cleveland reformer, councilman, journalist writing about his favorite mayor, Tom L. Johnson

first page:

A History of the Cooley Farms Complex

Cleveland, Ohio

By Jeffrey T. Darbee, Historic Preservation Consultant

Benjamin D. Rickey & Co. 593 South Fifth Street Columbus, Ohio 43206

Phone 614.221.0358 Fax 614.464.9357

Drew Rolik Research Associate

July, 2001

Introduction

This monograph on the Cooley Farms complex has been prepared as part of mitigation efforts associated with issuance of a Section 404 permit under the Clean Water Act of 1970. Under regulations implementing Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, the federal agency providing funding or licensing of an undertaking involving historic properties (in this case the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) must determine the undertaking’s effect upon any such properties and find means of mitigating any adverse effects. Since the Chagrin Highlands project proposed for the Cooley Farms site will result in demolition of all remaining historic structures on the site, recordation through photography and preparation of this monograph have been agreed upon by the concerned parties as the appropriate means of mitigating the structures’ loss.

Charity, Philanthropy, and Welfare in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County

The concept of public provision of aid to Ohio’s ill, destitute, and disabled citizens dates to the territorial period in the late 18th century. A 1790 law empowered township justices of the peace to appoint overseers of the poor, who advised local government officials on the type and; amount of aid needed by local citizens. Townships could levy taxes to support these efforts.

The 1790 law was re-enacted with minor changes in 1805, two years after Ohio’s statehood. A provision passed in 1807 required black settlers to post a $500 “freehold bond” in case they became dependent upon relief, but this was abolished in 1829.

In response to a long economic slump beginning during the War of 1812, Ohio in 1816 enacted a statute enabling county commissioners to establish poorhouses for the destitute. Since Cuyahoga County did not act on this matter, Cleveland did, constructing a two-story frame poorhouse in 1827 near the Erie Street Cemetery. This was the beginning of a long history of generosity toward the less fortunate for which Cleveland would become famous and which continues today. In 1837, when another economic slump hit and Cleveland had achieved a population of about 9,000, the city’s poorhouse sheltered some two dozen poor, sick, and insane people, with another 200 receiving publicly-paid medical care.

In 1849 the city levied a tax to pay for a hospital and a new poorhouse, to which nearby communities sent their needy citizens and for which they paid Cleveland. The city thus became the center of care for poor, ill, and disabled people from throughout Cuyahoga County.

An 1850 law replaced the term poorhouse with infirmary, and in 1855 Cleveland replaced its original poorhouse with a new infirmary on the west side, near where its modern equivalent, Metro General Hospital, stands today on Scranton Road.

The Civil War brought in its wake new demands for services to the poor, ill, and disabled. Widows and children of dead soldiers, as well as surviving veterans who were ill or disabled, were numerous, particularly since Cleveland’s population doubled between 1860 and 1870. The economic growth of that period meant plentiful jobs, but poverty remained a real fact, and the large city population always had its share of sick and disabled people. 1865 state legislation improved organization and accountability of county infirmaries and put their management on a more professional basis. This was just in time for the economic panic of 1873, which was especially severe.

Private Efforts

In 1866, Ohio was the second state to establish a state Board of Charities, a response to the growing private movement to aid the poor, sick, and disabled. Lacking access to public dollars that funded the city and county’s poorhouse/infirmary system, private efforts were nonetheless important and were part of the social context within which public efforts took place. Private philanthropic efforts dated to 1830 and the founding of the Western Seamen’s Friend Society. This relief agency, focused of the mariners who were making Cleveland one the major ports on the Great Lakes, had both a philanthropic purpose (promoting moral values) and a charitable one (providing emergency food and shelter). Other early efforts included the Martha Washington & Dorcas Society of 1843, a temperance organization that also attempted to relieve poverty; the Cleveland Women’s Temperance Union in 1850; the Ladies Bethel Aid Society in 1867; and the Soldiers’ Aid Society of Northern Ohio, active during and after the Civil War. Most if not all of these early philanthropic efforts had a strong religious base and combined charitable relief functions with strong moral instruction intended to help recipients avoid actions and lifestyles that landed them in poverty.

In the post-Civil War period, private philanthropy focused on specialized institutions addressing particular problems or population groups, but still with a strong religious association. In this period, several different orphanages were established, as were homes for abandoned infants, known as “foundlings.” The YMCA, formed in the 1850s, was re-established in 1867, and the YWCA came into being the next year, both at Superior and West Third streets. As the city’s population exploded in the postwar period, with a resultant increase in urban ills such as it is prostitution and out-of-wedlock pregnancies, as well as increased poverty, local philanthropists responded with institutions such as the Catholic House of the Good Shepherd in 1869 and the Stillman Witt Home, part of the Protestant Orphan Asylum, in 1873.

As the end of the 19th century approached, Cleveland’s immigrant population grew rapidly in response to the job opportunities presented by the city’s rapid industrial development. Local government at this time, as earlier, still focused on general relief for people in various states of distress, and private efforts had started to aim at particular social ills. As a result, another form of private response to social needs, the settlement house, evolved to serve primarily the immigrant population. Settlement houses in Cleveland began mainly during the last decade of the century, when immigration was particularly high, and included Hiram House (1896) at 2723 Orange Avenue, Goodrich House (1896) at Bond Street and St. Clair Avenue, Alta House (1898) at 12515 Mayfield Road, all of which were Protestant organizations; and the Jewish Council Educational Alliance (1897).

As private social agencies and organizations multiplied in the post-Civil War period, there was concern about overlapping efforts, unwise giving, and creation of a dependent class of aid recipients. In response, the Charity Organization Society came into being in January of 1881 in an effort to coordinate all charitable giving in the city. One of 22 similar organizations in the United States, the C.O.S. emulated the first in the country, established in Buffalo in 1877, the idea having originated in England in the late 1860s. The Society distinguished between “honestly” poor people who wanted to find work and those who avoided work and sought a free ride, and much of the impetus for the organization seems to have been to outsmart the latter through a careful screening and certification process. Over time, however, the C.O.S.’s continuing investigations of charity cases in Cleveland resulted in recognition of factors that contributed to poverty. The group became an advocate for day nurseries so women could work, and it maintained job registries for both men and women. In 1884 the C.O.S. joined the Bethel Union to form Bethel Associated Charities, which evolved into the Family Services Association and, later, into today’s Center for Human Services, which remains a private, non-profit organization.

Public Hospitals

Against this backdrop of government and private efforts to assist the poor, ill, and disabled of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, the city established public hospitals for those who could not find or afford private care.

The cholera epidemic of 1832 spurred creation of the first component of what would become Ohio’s largest public health system. The City Hospital of Cleveland was founded in 1837 on East 14th Street, not far from the city’s poorhouse. Its stated purpose was to heal the indigent sick, but within a few years it had lost its focus and had become an asylum for the poor, infirm, and insane citizens, much like the poorhouse.

This state of affairs continued for a half-century, until 1889, when Cleveland built the first true “City Hospital” on the Scranton Road site west of the river, just north of where the poorhouse/infirmary had been located since 1855. This was in a portion of Brooklyn Township that was annexed to the City of Cleveland in 1873. As noted earlier, the public facilities at the Scranton Road site would evolve into today’s MetroGeneral Hospital. Maps from the 1880s identify the site as “City Infirmary” and as the location of “insane wards,” but the facility also provided actual medical care. By 1892 it had a staff of 28 doctors and a training school for nurses.

The Rise of Progressivism

By the turn of the 20th century Cleveland had become a major industrial center and was one of the nation’s largest and most important cities. With this status also came big-city problems such as crime, disease, and poverty on a scale Cleveland had not seen before. These were aggravated by several factors, including rapid industrialization that attracted large numbers of both native and immigrant unskilled workers; low wages and high levels of poverty due to a surplus of these workers; difficulty in organizing workers to seek better conditions, due to employer opposition to unions and fragmentation of workers into hard-to-unify national and ethnic groups; and an increasing gap between rich and poor that left people at the low end of the economic scale with fewer and fewer resources to meet daily needs.

Conditions such as these in cities across the nation gave rise in the 1890s to what became known as the Progressive Movement. For the first time, both public and private individuals, many of whom had worked for a long time in various social welfare undertakings, came together as a national social and political force seeking basic changes in the country’s direction. Progressives saw the nation’s social ills as the result of increasing concentration of political and economic power in fewer and fewer hands as the power of large corporations grew. In response, the movement articulated three primary goals: 1) to make government more democratic; 2) to attain social justice; and 3) to achieve a better distribution of the national income and wealth.

Tom Johnson and Progressivism in Cleveland

Tom L. Johnson was born in Kentucky in 1854 and was destined to become the principal municipal leader of the Progressive Movement. Though raised in a well-off family, Johnson early learned, primarily from his mother, to shed all distinctions of class and to accept people of any position in life as his equal; he would always be remembered for his optimistic view of life.

Johnson found employment as a youthful office boy at a street railway in Louisville. Showing his aptitude for the business, he became superintendent within two years and was thus launched on the path that would make him wealthy. His first big success was the invention of a street car farebox that both registered fares and kept the coins visible to detect counterfeits. With profits from this popular product, Johnson eventually purchased street railways in St. Louis, Detroit, Brooklyn, and Cleveland, where he moved in 1879. In 1889, he established a steel mill in Johnstown, Pennsylvania and produced specialized “girder” rails for street railway use, a product that enjoyed wide success due to the rapid expansion of the nation’s urban areas and transit systems.

Johnson was an advocate Henry George’s ideas on free trade and the “single tax” on land, intended to correct the abuses and economic inequality fostered by the existing system of wealth ownership and taxation. These thoughts blended well with Johnson’s egalitarian attitudes and led to his entering politics. In 1890 he ran for and won a seat in Congress, representing Cleveland’s 21st District. During this time he fought for free trade and against the protective tariffs advocated by his Republican opponents in Congress. In 1901 he ran for mayor of Cleveland and won.

Election as mayor gave Johnson the position and power really to do something about the problems facing one of the country’s major cities. During his four terms (he was defeated by the Republican candidate in 1909), Cleveland would become known as the most progressive and reform-minded large city in the nation. Johnson campaigned on issues of fair taxation, home rule, and breaking up of monopolies. He was perhaps best remembered for promoting a three-cent street car fare and municipal ownership of public utilities and services, both intended to help the legions of poorly paid urban workers. Cleveland’s Water Department, in particular, became a model of a successfully run municipal service.

Harris Reid Cooley and the Development of Cooley Farms

In his ongoing fight against people of privilege and on behalf of the “common man,” Tom Johnson found a friend and soulmate in his church pastor, Harris R. Cooley. Three years younger than Johnson, Cooley was born in Royalton, Ohio on October 18, 1857. His father was Lathrop Cooley, a well-known minister in the Disciples of Christ church. He was active in various ministries in the Western Reserve for six decades, and he imparted to his son a sense of duty and obligation to the less fortunate members of society. The elder Cooley preached at the city workhouse, the city jail, and the Aged Women’s Home, and he served as superintendent and chaplain of the Cleveland Bethel Union, a seaman’s mission involved in work-relief programs.

Cooley’s son Harris trained for the ministry at Hiram and Oberlin colleges and served as pastor in several Cleveland and northeast Ohio churches. At Cleveland’s Cedar Avenue Christian Church he befriended Tom Johnson, and the two men soon found that they shared strongly held beliefs about social justice and economic and political equality.

One of those shared beliefs concerned the causes of criminal activity. Cooley and Johnson, like most Progressives, believed that the physical setting in which people lived actually influenced whether they would engage in criminal activity. The city itself— especially the run-down industrial districts and the neighborhoods where industrial workers lived — bred crime like a swamp breeds mosquitoes. A collateral problem was the disease and disability often found in these places. Both Cooley and his friend the mayor believed that humane treatment, both of the ill and of the criminally inclined, was essential to the recovery of both and that removal from the city setting was the appropriate way to achieve this goal. The city’s citizens would regain physical and social health by being removed from the city — an anti-urban attitude that shaped much of American social and economic policy during the 20th century.

In his work, Cooley would enjoy Johnson’s unwavering support. In his autobiography Johnson observed of Cooley:

“His convictions as to the causes of poverty and crime coincided with my own. Believing as we did that society was responsible for poverty and that poverty was the cause of much of the crime in the world, we had no enthusiasm for punishing individuals. We were agreed that the root of the evil must be destroyed, and that in the meantime delinquent men, women and children were to be cared for by the society which had wronged them ~ not as objects of charity, but as fellow-beings who had been deprived of the opportunity to get on in the world.”

Such attitudes were the beacon by which Johnson — and like-minded associates such as Cooley — would administer the city in the first decade of the 20th century. Often viewed by conservative interests as dangerously radical, in true Progressive fashion Johnson sought nothing more than to give common working people a better deal than they were getting.

Immediately upon taking office as mayor, Johnson appointed Cooley as Director of Charities and Corrections for the City of Cleveland. Cooley held this post for ten years, into the administration of Mayor Newton D. Baker. Acting on his theory that the crowding, dirt, noise, and other negative aspects of urban life militated against public health and healthy lifestyles, upon his appointment to his city post Cooley began to develop the idea of a rural campus, “wholesome surroundings” in which the city’s charges could be cared for without the evils of the city intruding. Mayor Johnson gave Cooley his vigorous support, and acquisition of land began in 1904. The location was in Warrensville Township, some 10 miles southeast of downtown Cleveland, on a high tract of rolling rural land. The city had already begun acquiring land here in 1902 for a cemetery and between 1904 and 1912 acquired some 25 farms at a total cost of $350,000. The complex eventually totaled 2,000 acres, located primarily between Northfield and Richmond roads (which ran north-south) and on either side of Harvard Road (which ran east-west).

Cooley himself expressed the purpose of the new facility in terms which summed up his philosophy and his attitude toward his fellow man — terms which might be considered softhearted and romantic by some but which went to the core beliefs of this unusual public official. Speaking of the indigent and the delinquent in particular, Cooley said:

“They have made the human voyage. Among the unfortunates are some who have been wasteful, intemperate, and vicious. Some are undeserving, some have done wrong, but these things are true of some of the children of luxury.”

The entire complex became known as Cooley Farms and became widely known for its progressive approach toward the people in its care. Consistent with Cooley’s and the mayor’s ideas about crime, the complex also included a correctional facility for rehabilitation of lawbreakers. Attitudes of the time held that negative influences of the urban setting contributed to crime and vice and that removal of offenders from that environment was essential to their “correction.” The Cleveland Workhouse was first established in 1855 on the Scranton Road site near the city’s hospital and infirmary. It moved in 1871 to a site on Woodland Avenue at East 79th Street, and in 1912 it became part of Cooley Farms.

There were four components of Cooley Farms, all of which were in place by the period just before World War I. They included Colony Farm, which was the city infirmary/poorhouse, which also included a halfway house and cottages for elderly couples; Highland Park Farm, the city cemetery; Overlook Farm, a tuberculosis sanatorium; and Correction Farm, the city workhouse and house of corrections. The first two were north of Harvard Road, the cemetery in the northwest quadrant and Colony Farm in the northeast quadrant. The other two were south of Harvard, the Correction Farm in the southwest quadrant and Overlook Farm in the southeast. Each of the four occupied about 500 acres.

Adoption of the name “Farms” was not just to commemorate the original use of the land. Social philosophy of the time held that productive work was important in rehabilitating people of all kinds, from the aged and ill to the poor and the criminal. Thus the Cooley Farms complex was set up as a working farm, nearly self-sufficient, where everyone was expected to work according his physical and mental ability. Workhouse inmates did the heaviest work, which included operation of a quarry for building stone and cement production. They worked at the facility’s dairy, piggery, greenhouse, blacksmith shop, sawmill and cannery. Farm work included vegetable and feed production and an orchard. Workhouse inmates also maintained the grounds of the entire complex and worked on construction of many of the buildings. Able-bodied residents of the other “farms” also worked, mainly at lighter tasks. The entire Cooley Farms complex was considered a model for progressive treatment of social ills, the workhouse in particular. Social and economic journals of the day devoted considerable space to studies of the complex, and the Cleveland facility inspired similar efforts in Toledo and in two cases in New York City, the Farm Colony on Staten Island and the 1930s Camp LaGuardia in rural Orange County, intended for derelicts from the Bowery.

The workhouse at Correction Farm, completed in 1912, was also called the Cooley Farms Workhouse and the Cleveland House of Corrections. A women’s wing was added in 1913, and a separate boiler house was part of the original construction. The architect was J. Milton Dyer, a major Cleveland architect who had to his credit such important structures as Cleveland City Hall, the Peerless Motor Car Company, and the U.S. Coast Guard Station. The buildings employed a restrained Spanish Colonial Revival style, represented primarily by their red clay tile hip roofs and stuccoed walls. They were replaced by new facilities in the mid-1980s, and no historic structures survive at the site today.

Overlook Farm, the tuberculosis sanatorium, was first located in the Robert J. Walkden house, one of the farmhouses acquired by the city when it was making land purchases for Cooley Farms. Located on the west side of Richmond Readjust north of Harvard Road, the house served from 1906 until completion of the main sanatorium in 1913. The Walkden house was an 1870 Italianate building of brick construction. It had been unused and was in a state of deterioration at the time it was destroyed by fire in 1982.

The 1913 sanatorium was known as both Sunny Acres Sanatorium and Sunny Acres Hospital (exposure to sunlight was at one time thought to help cure tuberculosis). Both the main building and a 1931 addition were designed in a simplified Mission Revival style, which complemented the Spanish Colonial Revival elements of the Cleveland Workhouse and the Colony Farm. The 1913 building was designed by Herman Kregelius, and the 1931 addition was designed by George S. Ryder. The original facility, and its 1931 addition, survived into the late 1970s, when they were demolished for a new facility, which still serves as part of the county’s health care system as a long-term skilled nursing facility. No historic structures remain at the Sunny Acres site today.

The principal buildings of the Colony Farm, which was the replacement for the old City Infirmary at the Scranton Road site near downtown, were completed between 1909 and 1912.

Other later structures, discussed below, expanded the complex, and a large new main hospital building was built in the early 1950s after the complex was transferred to Cuyahoga County. It was about this time that the complex became known as Highland View Hospital. The sit was on the north side of Harvard Road west of Richmond Road.

The original complex included eight buildings: the Old Couples’ Cottage, the Female Insane Cottage, the North Dormitory, the Administration Building, the Quadrangle, the Power House, the South Dormitory, and the Male Insane Cottage. The design of the complex was the work of J. Milton Dyer, architect of the workhouse. The symmetry of the complex indicated the formality of the Beaux-Arts design Dyer originally proposed, which was abandoned in favor of the modest Spanish Mission-influenced design ultimately built.

The complex at its peak had fifteen separate structures and today consists of nine standing buildings and one set of ruins. Four of the buildings standing on the site were listed in the National Register of Historic Places on August 8, 1979, including original Colony Farm buildings known today as Sweeney Hall, Bingham Hall, the Quadrangle Building, and Carter Hall; the nomination was prepared by the Cuyahoga County Archives and was called “Cooley Farms Group.” The nomination also included the Cleveland House of Corrections, the House of Corrections Boiler House, and the Robert J. Walkden House. As was noted above, all of these buildings have been demolished.

The combined Sanborn maps of 1926-51/1953-61 give a picture of the hospital complex when it had reached its greatest size. From north to south, the principal buildings by the late 1950s included the following:

1. Highland View Hospital, originally known as the Cuyahoga Chronic Hospital and currently as the Main Building, built between 1951 and 1953. The building is still standing and is cross-shaped in plan. At its southeast end is a synagogue and an addition known as Reynolds Hall, both built in 1957. The hospital and additions were built of concrete and brick in a modified Moderne style typical of the early 1950s, with banded aluminum windows and no architectural ornamentation.

2. The Chronic Hospital (so called on the Sanborn Map), still standing and today called the Blossom Building. Its main elevation faces south, and it is attached on its north side to the south end of Reynolds Hall. The Blossom Building was built in 1932 in a spare Moderne design with modest amounts of stylized ornamentation and steel windows.

3. The Old Couples’ Cottage, which was in place by 1910 and was one of the original buildings in the complex. It was demolished at some point in the past, possibly the 1970s or 1980s.

4. The Female Insane Cottage, still standing and known today as Sweeney Hall. It dates from the original construction period of the hospital complex, completed in 1912, and it has the same Spanish Colonial Revival style elements found in other original buildings to the south and west. These elements include a red clay tile roof, exposed roof rafter ends, stuccoed wall surfaces, and some use of arched openings.

5. The North Dormitory, today called Bingham Hall. It is still standing and also dates from the 1912 original construction period. This building, too, was built with Spanish Colonial Revival style architectural elements and was part of an assemblage of buildings, as can be seen on the Sanborn map.

6. The administration building, located west of the main quadrangle and probably built about 1912 along with the other original buildings. This building was demolished at an unknown date, possibly in the 1970s or 1980s.

7. The original Quadrangle Building, also built in 1912 as part of the original complex. Like Sweeney and Bingham halls, this building had elements of the Spanish Colonial Revival style. It was a true quadrangle, with an open courtyard in the center. The west and north legs were demolished in the 1960s, leaving an L-shaped building which today is still called the Quad Building.

8. The Power Plant is of indeterminate date and is still standing, attached to the east side of the Quad Building. The chimneys and other portions of the plant probably are original, since the complex’s remote location around 1912 likely would have meant that public utilities were unavailable. The plant would have provided steam for heating and would have generated electric power for the complex. The Power Plant has been modified over the years, and all its equipment appears to have been removed, but the building and chimneys are still standing. The Power Plant appears to be included in the National Register nomination (this conclusion is based on the map of the Cooley Farms Group, which appears to show the Power Plant attached to the east side of the Quadrangle Building), but it is not identified as a separate structure.

9. The eastern dormitory building, today called East House. This building, which is still standing, was built with Spanish Colonial Revival style elements and probably dates from the c!912 period. Its remote location suggests that it may have housed contagious patients, but this has not been verified.

10. South of East House was a greenhouse, which was demolished at an unknown date, possibly the 1970s or 1980s.

11. The South Dormitory, standing today and called Carter Hall. It was built in a “mirror” design of the North Dormitory and, together with the Administration Building and the Quadrangle Building, formed a symmetrical west-facing cluster of buildings of common architectural design. Dating from 1912, it formed part of the original core of the hospital complex.

12. Twin garages, built of brick and each of 10-car capacity. They appear to have had flat roofs. Both were destroyed by fire some time ago and today consist only of brick rubble. Their original date is unknown.

13. Building 54, which probably was the Male Insane Cottage, judging from its footprint and its location on the site. It dated from some time around the original construction and was demolished at some time in the past, possibly the 1970s or 1980s.

14. The Central Laundry Building, still standing and built in 1950. The building was functional in design, with brick walls, a flat roof, industrial-style windows, and no ornamentation.

15. As noted on the Sanborn map, a Recreation Building and a Dining Hall were located adjacent to a swimming pool. These were 800 feet southwest of the South Dormitory (Carter Hall), which would have placed them south of Harvard Road, which runs along the south side of the complex. These two buildings and the pool were demolished at an unknown date.

Other surviving elements of the site include concrete walks, paved drives and parking areas, and portions of former tunnels and covered passageways that provided all-weather access between some buildings. There are numerous trees and shrubs, many of which obviously were part of the site’s landscaping; others have grown up since the property was abandoned in the early 1980s.

Under the county’s administration, Highland View Hospital became well known for its care of chronically ill patients, specializing in treating the chronically disabled, stroke victims, and patients with neuro-muscular diseases. In 1957-58 the Cuyahoga County Hospital system was established and was credited with being the nation’s first county-run public hospital system. Highland View and City Hospital (now MetroHealth Medical Center, at the original Scranton Road location) were the system’s two principal units.

Between 1969 and 1973, the county began a move to phase out Highland View in favor of MetroGeneral Hospital at the location near downtown Cleveland. This decision apparently was made for financial reasons, to cut the cost necessary to run two large hospital complexes. By 1978 the last of Highland View’s patients was transferred to MetroGeneral. Other than use of two wings of the Main Building in the early 1980s as an alcoholism treatment center, the buildings at Highland View were never used again. The site was proposed for redevelopment during the 1980s by a local industrialist, but these plans never materialized. More recently, the property has been transferred to a Cleveland developer and is proposed for long-term commercial development.

MetroGeneral Hospital

Back near downtown Cleveland, after removal of the non-medical functions to Cooley Farms by the period just before World War I, City Hospital continued to operate in both the 1889 structure and in the former infirmary building. A tuberculosis sanatorium was established at the site in 1903, and the complex also cared for the insane, but these functions also were moved out by the mid-‘teens. From that period forward, the focus of the facility was on medical care, primarily for the indigent.

The distinction between the early institutions appears to have been that the City Hospital was for those suffering from short-term ailments and injuries, while the Infirmary was intended for people with chronic and long-term health problems. The long distance from the city apparently was thought not to be an inconvenience for such patients, perhaps because they were thought of as permanent residents with little need to leave the facility.

At MetroGeneral Hospital, there has been considerable demolition and re-building at the site, but three major structures — the General Hospital Building, the Psychopathic Building (both built in 1922), and the Nurses’ Residence (1926) — survive with a high level of integrity as excellent representatives of Cleveland’s early public health institutions.

Recommendations for Future Study

All of the historic structures at the Cooley Farms site will soon be gone as redevelopment goes forward. This will leave MetroGeneral Hospital’s historic buildings as the only ones remaining with a connection to city and county efforts to create large-scale public health facilities. For this reason, National Register nomination of Metro General’s surviving historic structures should be a high priority.

Other avenues of study could also be fruitful. For example, the schedule and budget for preparation of this monograph did not permit extensive use of primary source materials associated with the relationship between Cooley and Johnson and their decision to build the farm complex.

An identification and evaluation of any such materials would shed additional light upon the relationship of the two men and how they put their Progressive principles into practice in Cleveland.

In addition, study of the opposition ~ conservative, anti-Progressive economic and political interests — could help establish more of the context with which the Cooley Farms complex was created and operated. Such a large-scale effort, though successful, would not have gone forward without at least some opponents raising red flags. Newspapers of the time, in particular, could give a vivid picture of the opposing forces at work as early 20th century Cleveland struggled to deal with the issues of its new industrial economy.

Fred Kohler Speech on “A Golden Rule” to International Association of Chiefs of Police in Detroit MI June 3, 1908

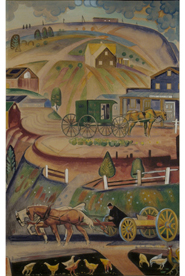

The Cleveland School – Watercolor and Clay by William Robinson

From the Canton Museum of Art

The Cleveland School

Watercolor and Clay

Exhibition Essay by William Robinson

Northeast Ohio has produced a remarkable tradition of achievement in watercolor painting and ceramics. The artists who created this tradition are often identified as members of the Cleveland School, but that is only a convenient way of referring to a diverse array of painters and craftsmen who were active in a region that stretches out for hundreds of miles until it begins to collide with the cultural orbit of Toledo, Columbus, and Youngstown. The origins of this “school” are sometimes traced to the formation of the Cleveland Art Club in 1876, but artistic activity in the region predates that notable event. Notable artists were resident in Cleveland by at least the 1840s, supplying the growing shipping and industrial center with portraits, city views, and paintings to decorate domestic interiors.

As the largest city in the region, Cleveland functioned like a magnet, drawing artists from surrounding communities to its art schools, museums, galleries, and thriving commercial art industries. Guy Cowan moved to Cleveland from East Liverpool, a noted center of pottery production, located on Ohio River, just across the Pennsylvania border. Charles Burchfield came from Salem and Viktor Schreckengost from Sebring, both for the purpose of studying at the Cleveland School of Art. To be sure, the flow of talent and ideas moved in multiple directions. Leading painters in Cleveland, such as Henry Keller and Auguste Biehle, established artists’ colonies in rural areas to west and south. William Sommer, although employed as a commercial lithographer in Cleveland, established a studio-home in the Brandywine Valley that drew other modernists to the country. So, while the term “Cleveland School” may not refer to a specific style or a unified movement, it does identify a group of interconnected artists active in a confined geographic region, many of whom who shared common experiences, backgrounds, training, professional challenges, and aesthetic philosophies.

The Cleveland School enjoys a well deserved reputation for achievement in watercolor painting. In May 1942, Grace V. Kelly commented in the Plain Dealer: “Watercolor painting is the special pride of Cleveland and the medium through which its artists are known to connoisseurs throughout the country.” Interest in the medium grew modestly during the nineteenth century, and then accelerated after the founding of the Cleveland Society of Watercolor Painters in 1892. At the time, many people still considered watercolor a form of drawing and inferior to oil painting. After the turn of the century, artists increasingly altered their approach as they began thinking of watercolor, not as tinted drawings, but as an independent form of painting with unique aesthetics and technical issues. The key aspect of watercolor that sets it apart from other painting media is transparent color. Applying thin washes of transparent watercolor over white paper allows light to penetrate the paint layer and reflect off the paper, thereby illuminating the colors with a special radiance. This effect can be enhanced by combining watercolor with areas of opaque gouache and white body color. From a technical standpoint, watercolor is an extremely medium difficult because the liquid paint is quickly absorbed into the paper and dries almost immediately, making it nearly impossible to rework a composition without muddying the colors. Watercolor painters must work swiftly and accurately because there is almost no margin for error.

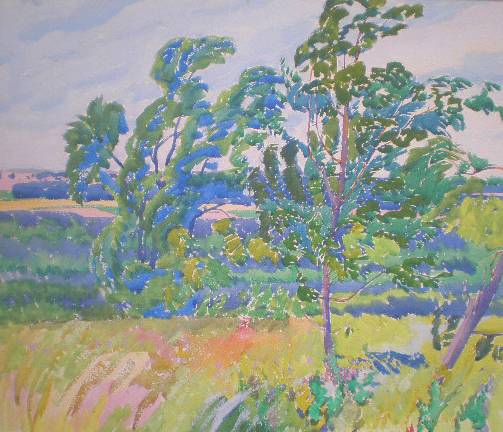

The artists of northeast Ohio developed their own watercolor traditions and raised the medium to such heights that it stands out as an area of special achievement. They learned to exploit the medium’s most distinctive quality—transparency—and to paint quickly and freely, sometimes without preliminary drawing. Ora Coltman (1858-1940) from Shelby, Ohio, was among the early practitioners of the medium. Like other artists of his generation, he found watercolor ideal for making travel sketches and deftly exploited the medium’s inherent transparency to evoke the intensity of sun-drenched, outdoor light. Henry Keller (1869-1949), who taught at the Cleveland School of Art from 1903 to 1945, masterfully employed both transparent and opaque watercolor, also known as gouache. His works range in style from experiments in abstract design, such as Futurist Impression: Factories, to freely rendered views of the Ohio countryside and the beaches of La Jolla, California. A highly influential teacher, Keller introduced a generation of his students and colleagues to modernist principals of abstract design and color theory. He began experimenting with abstract design as early as 1913, the year he exhibited in the Armory Show. Grace Kelly (1877-1950) and Clara Deike (1881-1918) were among the many artists who painted outdoors with Keller at the summer school he established in Berlin Heights, Ohio, in 1909. The large, flat planes of abstract color—especially the intense blue shadows—in Deike’s Sunflowers with Chickens and Kelly’s Cypress are signature features of the modernist style developed by Keller and his colleagues.

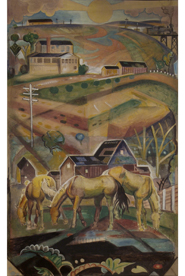

Auguste Biehle (1885-1979) and William Sommer (1867-1949), two of the most important and influential pioneers of modernism in Ohio, worked in Cleveland’s commercial art industries. Biehle studied in both Cleveland and Munich. After attending the first exhibition of the German Expressionist group, The Blue Rider, Biehle returned to Cleveland in 1912 and began painting in an avant-garde style that merged abstract color with decorative design. Like many of his Cleveland colleagues, Biehle was a versatile artist who worked masterfully in variety of styles, from modernist abstraction to American scene realism.

William Sommer deserves special recognition as one of the finest American watercolorist of the twentieth century. Born in Detroit, Sommer came to Cleveland in 1907 to work for the Otis Lithograph Company, where he developed a close relationship with William Zorach (1887-1966). Together, they became leaders in the regional avant-garde movement. In 1911, Sommer helped establish two organizations dedicated to advancing modernist art in Cleveland: the Secessionists and the Kokoon Klub. In 1914, he converted an abandoned school house in the Brandywine Valley, about 20 miles south of Cleveland, into a home and studio that attracted visits from progressive poets and painters, including Hart Crane and Charles Burchfield. Sommer continued painting in a modernist style during the 1920s and 1930s, a period when many artists abandoned abstraction for American scene realism. Sommer’s large watercolor U.S. Mail interprets rural Ohio through the modernist lens of flattened and compressed space, powerfully reductive forms, and inventive color.

Although often described as an isolated, self-taught artist working in the rural hinterlands of America, Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) was an extremely sophisticated painter who learned principles of modernist composition and color theory through Henry Keller, his teacher at the Cleveland School of Art from 1912-1916. Burchfield also discovered avant-garde art by frequenting exhibitions at the Kokoon Klub and by traveling to Brandywine in 1915 to meet “Big Bill Sommer.” It was during this period that Burchfield developed his signature style and ideas about the nature of the creative process. He shared Sommer’s philosophy of using watercolor as a means of externalizing emotions and exploring subconscious fears and dreams by painting quickly and intuitively. Burchfield once explained why he adopted watercolor as his ideal medium: “My preference for watercolor is a natural one . . . whereas I always feel self-conscious when I use oil. I have to stop and think how I am going to apply the paint to canvas [when working in oil], which is a determent to complete freedom of expression . . . To me watercolor is so much more pliable and quick.”

Led by Burchfield, Sommer, Biehle, and their colleagues, a nationally distinguished school of watercolor painting emerged in northeast Ohio during the early years of the twentieth century. They exploited the inherent advantages of watercolor for painting quick, lively views of American scene subjects. Frank Wilcox (1887-1964) developed a masterful à la prima technique for portraying the rural countryside and imagined scenes of Ohio history. William Eastman (1888-1950) depicted the recently constructed Terminal Tower in Cleveland rising against a sunset sky with ominously dark clouds. Clarence Carter (1904-2000) came to Cleveland from Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1923, and developed a national reputation as an imaginative interpreter of American scene subjects, accomplished with a personal blending of realism and modernism.

Carl Gaertner (1898-1952) began haunting the city’s steel mills and factories during the early 1920s and rapidly established himself as a preeminent painter of industrial Ohio, renowned for his dark, moody, deeply expressive winter scenes. Other prominent watercolor paintings of this generation include Lawrence Blazey, Carl Broemel, Charles Campbell, Kae Dorn Cass, Joseph Egan, William Grauer, Joseph Jicha, Earl Neff, Paul Travis, and Roy Bryant Weimer.

Cleveland artists of the next generation continued to develop this regional tradition in watercolor painting. Hughie Lee-Smith, Moses Pearl, Kinely Shogren, and Joseph Solitario were all born after the outbreak of World War I, yet largely followed in the footsteps of their predecessors in using watercolor to record exacting images of life in modern America. One of the most distinguished African-American artists of his time, Lee-Smith came to Cleveland in 1925, took studio classes at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland School of Art, and taught at the Playhouse Settlement (Karamu House) from the 1930s to the early 1940s. His haunting images of lonely and deserted urban settings, sometimes occupied by a few isolated figures, seem symbolic of the alienated condition of African-Americans during a period of pervasive Jim Crow laws, lynchings, a resurgent KKK, and segregation in the military. Solitario recorded memorable images of weary, bored soldiers traveling by train during World War II. Pearl spent a lifetime painting watercolors of Cleveland urban and industrial sites, starting from his teen years in the 1930s to his death in 2003.

Art historians have praised northeast Ohio for its long tradition of excellence in decorative arts and crafts. R. Guy Cowan (1884-1957), a pioneer in the production of fine art ceramics, established studios that attracted leading talents from around the region and served as a center for collaborative production. Born to a family of potters in East Liverpool, Ohio, Cowan settled in Cleveland in 1908 after studying at the New York State School of Clayworking and Ceramics. He founded the Cleveland Pottery and Tile Company in 1913, and later the Cowan Pottery Studios in nearby Lakewood and Rocky River. Cowan’s early works, such as his Lusterware Vase of 1916-17, feature simple yet elegant forms, reflecting the aesthetics of the nineteenth-century Arts & Crafts Movement, accentuated by delicate, monochromatic glazes. Cowan attracted national attention and awards for his ceramics as early as 1917. Critics praised his unique glazes, spectral colors, and high quality materials. During the 1920s, he produced critically acclaimed ceramic figurines in an Art Deco style, as exemplified by Flower Frog with Scarf Dancer of 1925. Adam and Eve of 1928 energizes and unites two figures through decorative rhythms that flow electrically across space.

Cowan began teaching at the Cleveland School of Art in 1928. He used his contracts there to bring leading artists to his studio in Rocky River to collaborate on the production of ceramics, launching a regional renaissance in the medium. Cowan Pottery attained national acclaim prior to its closing in December 1931. Among the notable artists who worked there were: Walter Sinz, Alexander Blazys, Thelma Frazier Winter, Edris Eckhardt, Waylande Gregory, Russell Aitken, and Viktor Schreckengost.

Nationally renowned for his work as a ceramist, industrial designer, painter, and teacher, Schreckengost was born in 1906 to a family of potters in Sebring, Ohio. After attending the Cleveland School of Art from 1924 to 1929, he spent a year studying ceramics at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, and then returned home to find the nation in the midst of the Great Depression, but lucky enough to receive a joint appointment shared between his alma mater and the Cowan Studios. He produced his famous New Yorker or Jazz Bowl at the Cowan Studios in 1931. Commissioned by Eleanor Roosevelt to celebrate his husband’s re-election as governor of New York, the bowl interprets a distinctly American subject—the city at night bursting with the energetic rhythms of jazz—in a lively, Cubist style. Schreckengost noted that the subject was inspired by a night he spent at the Cotton Club listening to Cab Calloway. To suggest a sense of the city at night, Schreckengost employed an innovative sgraffito technique of scratching through a lustrous black upper glaze to expose the deep Egyptian blue below. The bowl was so popular that he created versions in different sizes and glazes. Schreckengost also excelled at incorporating caricature and humor into his ceramics, as seen in his plates devoted to sports, part of an attempt, so he said, to lift the spirits of people devastated by the Depression. The infectious humor of his ceramics seems to have rubbed off on his colleagues at Cowan, who followed the same path of emphasizing light-hearted, whimsical subjects as an antidote to the brutal realities of the era.

After 1945, a new emphasis on geometric abstraction emerged in Schreckengost’s ceramics and watercolors. The same trend appears in the post-war ceramics of other Cleveland School artists, including Claude Conover, Leza Sullivan McVey, and Clement Giorgi. Increasing experimentation with organic forms and delicate glazes also suggests the influence of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s growing collection of Asian art.

Although American artists shifted their focus away from regional schools after the end of World War II, northeast Ohio remained a thriving center of activity in watercolor painting and ceramics. Today, members of the Ohio Watercolor Society come from every corner of the state and actively organize exhibitions that enrich the lives of people in urban and rural communities alike. Northeast Ohio is also dotted with studios, workshops, teaching programs, and societies devoted to ceramics. Museums dedicated to ceramics can be found from East Liverpool to Rocky River. Watercolor painting and ceramics should be celebrated in northeast Ohio, not only as historical artifacts of artistic achievement, but as vital cultural activities that continue to bind the region together.

Image Credits:

“Futuristic Impressions Factory” by Henry Keller, Courtesy of Rachel Davis Fine Arts

Summer Landscape by Grace Kelly, Courtesy of Michael & Lee Goodman

US Mail/Brandywine Landscape by William Sommer, Purchased in Memory of John Hemming Fry, Canton Museum of Art, 2011.18.A.B

“Buildings” by Carl Gaertner`, Courtesy of Rachel Davis

“Jazz Bowl” by Viktor Schreckengost, Courtesy of Thomas W. Darling

“First Nighter” by Edris Eckardt, Courtesy of a private collection

Notes:

[1] According to Mark Bassett, the term “Cleveland School” was first used by Elrick Davis in article published in the Cleveland Press in 1928.

[1] Grace V. Kelly, “May Show’s Watercolors Maintain Usual High Levels Despite Wartime Pressures,” Cleveland Plain Dealer (May 10, 1942), B:12.

[1] “Charles Burchfield Explains,” Art Digest 19 (April 1, 1945), 56.

Section on West Park and Kamm’s Corners from Fresh Water Cleveland

Plain Dealer article (8/29/10) written by John Soeder about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame after 15 years.

Courtesy of Cleveland Plain Dealer

Short Documentary about Cuyahoga River fires produced by CSU Digital Humanities

Article published September 24, 1999

Visionary mayor used Golden Rule in business, politics

Apolitician almost by accident, he struck fear into the hearts of the political elite of the day.

A sitting U.S. president, the speaker of the U.S. House, and the leader of the Senate traversed Ohio campaigning against him, trying to mute the strong appeal of his populist message.

He was Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones, a penniless man who became a millionaire businessman before turning his attention to politics, where he was one of the nation’s foremost political reformers as mayor of Toledo. A stubborn man who hated political parties because of the corruption they encouraged, Mr. Jones ran his company and his administration based on the Biblical precept that one should treat others as one would want to be treated.

He gained national attention for his municipal reforms and for his success in fighting corruption.

He died during his eighth year in office, but the legend of Samuel Jones lives on – nearly 100 years after his death, experts have rated him the fifth-best mayor in United States history.

Mr. Jones arrived in Toledo from Wales via Pennsylvania and Lima, establishing the Acme Sucker Rod Co., which made oil drilling equipment. He won the nickname “Golden Rule Jones” for the policies he implemented at the firm, including the eight-hour workday, paid vacations, and a company park for his employees.

In 1897, with the local Republican Party badly split over whom to offer as a mayoral candidate, they settled on him as a compromise. He won but quickly fell out of favor with the GOP because of his refusal to fulfill their patronage demands. He ran and won re-election as an independent in 1899, winning 70 per cent of the vote.

He served until his death in 1904.

While in office, he implemented many reforms, including a civil service system for police officers and firefighters, and he was known for bringing his “Golden Rule” philosophy to city government, preaching love and forgiveness and light sentences for petty crimes.

When a group of local ministers urged him to force prostitutes out of town, he asked “To where?” Mayor Jones suggested that the ministers take the girls into their homes to shelter them and pledged that, if the ministers would comply, he and Mrs. Jones would do the same.

He was criticized for not closing city bars on Sundays, but he maintained Toledoans worked long and hard six days a week and deserved their beer on the seventh.

In 1899, a few months after winning re-election, he became an independent candidate for governor, though some in the state Republican Party tried to entice him to run for the GOP nomination.

To quash Mr. Jones’s candidacy, New York Gov. Teddy Roosevelt, U.S. House Speaker David Henderson, U.S. Senate President Pro Tem William Fry, and both of Ohio’s senators traveled the state campaigning against him, and for George Nash, who won. Even President William McKinley, an Ohio native who did not campaign for his own presidency three years before, traveled the state to speak on behalf of Mr. Nash, causing the Toledo News Bee newspaper to wonder: “What office is William McKinley running for this year?”

On election night, as the vote totals flowed into election headquarters in the Valentine Building in downtown Toledo, Mayor Jones called his strong third-place finish and his effort to fight the two-party system a “moral victory,” saying his independent candidacy won more votes than any other such effort in Ohio history.

He carried Toledo by 2,270 votes after having spent $250 on his campaign here. In Cuyahoga County, he won 54 per cent but lost badly in rural areas.

Eventually, the reforms that Mr. Jones fought for became commonplace in the American work force and in government. But because of his foresight and commitment to the “Golden Rule,” he has earned a lasting place in American political history.

Dr. John J. Grabowski holds a joint position as the Krieger-Mueller Historian and Vice President for Collections at the Western Reserve Historical Society and the Krieger-Mueller Associate Professor of Applied History at Case Western Reserve University. He has been with the Society in various positions in its library and museum since 1969. In addition to teaching at CWRU he serves as the editor of The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History and The Dictionary of Cleveland Biography, both of which are available on-line on the World Wide Web (http://ech.cwru.edu). He has also taught at Cleveland State University, Kent State University, and Cuyahoga Community College. During the 1996-1997 and 2004-2005 academic years he served as a senior Fulbright lecturer at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey. Dr. Grabowski received his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in history from Case Western Reserve University. He is a member of Phi Beta Kappa.

1957 corridor report for interstate and alternative routes in Cuyahoga County

From CSU Special Collections