Edgar Byers from “Freedom’s Forum” by Dr. Thomas Campbell

“Regionalism and Shaker Heights” forum Aug 18, 2016

“Regionalism and Shaker Heights” forum Aug 18, 2016

“Regionalism and Shaker Heights” Aug 18, 2016

Issues facing almost all of Northeast Ohio’s suburbs

w/Panelists:

Armond Budish, Cuyahoga County Executive

Edward Kraus, Cuyahoga County Director of Regional Coordination

Earl M. Leiken, Mayor, City of Shaker Heights

Hunter Morrison, Director, NE Ohio Sustainable Communities

Consortium

Moderator:

Judy Rawson, Former Mayor, City of Shaker Heights

Thursday August 18, 2016 7-8:30 p.m.

Shaker Public Library, 16500 Van Aken Blvd, 44120

Cost: Free & Open to the Public

Cosponsored by

Shaker Public Library & League of Women Voters-Shaker Chapter

“Redistricting and Voting Rights in Ohio” forum August 25, 2016

“Redistricting and Voting Rights in Ohio” August 25, 2016

Panelists:

Representative Kathleen Clyde (D), Ohio House District 75

Dr. John C. Green, Director, Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics

Senator Frank LaRose (R), Ohio Senate District 27

Moderator: Thomas Suddes, Editorial Writer, Cleveland.com

Overall Theme:

As with weather, everyone talks about gerrymandering — drawing legislative districts to favor one party over another — but until recently, few in Ohio were prepared to do anything about it. Nonetheless, Ohio has recently reformed how its draws General Assembly districts — and reform of congressional “districting” is on some Columbus agendas. This panel explores the hows and whys.

CWRU Siegal Facility, 26500 Shaker Blvd., Beachwood OH 44122

Cost: Free & Open to the Public

Co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University Siegal Lifelong Learning Program, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland, Cleveland.com, Plain Dealer plus Lakewood and Cuyahoga County Library Systems

Corporate sponsor: First Interstate Properties, Ltd.

Water Quality of Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River Forum 9/15/16

Water Quality of Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River Forum 9/15/16

Thursday September 15, 2016 7-8:30p.m.

Panelists:

Kyle Dreyfuss-Wells, Deputy Director of Watershed Programs, NEORSD

Jane Goodman, Executive Director, Cuyahoga River Restoration

Jim White, Director, Sustainable Infrastructure Prog., Port of Cleveland

Moderator: Jim McCarty, Metro Reporter, The Plain Dealer

Our panel addressed the vital water issues in Northeast Ohio, specifically in Lake Erie, the Cuyahoga River and the other creeks, streams and rivers that empty into the lake. We discussed harmful algal blooms, PCBs and Mercury pollution, invasive species, the impending removal of 2 dams on the Cuyahoga River, the ongoing conflict with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over the disposal of dredged material, and the status and success of the NE Ohio Regional Sewer District’s multi-billion dollar tunnel project.

Cost: Free & Open to the Public

Fairview Park Branch, Cuyahoga County Public Library

21255 Lorain Road, Fairview Park 44126

Co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University Siegal Lifelong Learning Program, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland, Cleveland.com plus Lakewood and Cuyahoga County Library Systems

Corporate sponsor: First Interstate Properties, Ltd.

“Marijuana Legalization in Ohio” forum Thursday October 13, 2016

“Marijuana Legalization in Ohio” forum Thursday October 13, 2016

Panelists:

Kelly Kefauver, Senior Legislative Aide to Senator Kenny Yuko, Ohio Senate

Breanna Stabler, Administrative Aide to Senator Kenny Yuko, Ohio Senate

Dr. Brian Bachelder, President of OSMA and Family Physician at Akron Gen Hosp

Garett Fortune, CEO, FunkSac, Compliant Packaging for the Cannabis Industry

Thomas G. Haren, Seeley, Savidge, Ebert & Gourash., L.P.A., editor, OH Marijuana Law Blog

Moderator: Jackie Borchardt, Columbus Bureau Reporter, Cleveland.com

Ohio became the 25th state to legalize medical marijuana earlier this year but the debate about cannabis reform is far from over in the Buckeye State. Rules for the medical marijuana program will be written in the coming months, and advocates as well as the national group that had spearheaded a competing ballot initiative are pushing lawmakers to make good on promises made when they approved the program. What will Ohio’s medical marijuana program look like? And what does the law mean for future marijuana reform efforts in Ohio?

Co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University Siegal Lifelong Learning Program, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland, Cleveland.com, Plain Dealer plus Lakewood and Cuyahoga County Library Systems

Corporate sponsor: First Interstate Properties, Ltd.

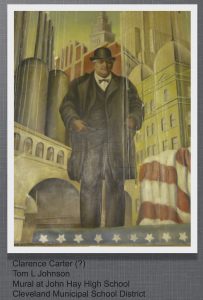

Tom L. Johnson Mural at Cleveland’s John Hay High School

Tom L. Johnson Mural at Cleveland’s John Hay High School

To read more about Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson (1901-1909), click here

“Regionalism and the West Shore Communities” forum 11.14.16

“Regionalism and the West Shore Communities” forum 11.14.16

Panelists:

Pamela Bobst, Mayor, City of Rocky River

Armond Budish, Cuyahoga County Executive

Dave Greenspan, Cuyahoga County Council, District 1

Edward Kraus, Director of Regional Coordination, Cuyahoga County

Michael Summer, Mayor, City of Lakewood

Moderator: Janice Patterson, LWV-Greater Cleveland

The panel discussed current initiatives in the delivery of services in Cuyahoga County. They explored possibilities for future cooperation and responded to audience comments and questions.

Sponsored by the League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland and Lakewood Public Library

“Relationship Between Cleveland Police and the Community” forum 11/15/16

“Relationship Between Cleveland Police and the Community” forum 11/15/16

Panelists:

Blaine A. Griffen, Exec. Dir, Community Relations, City of Cleveland

Deon McCaulley, Deputy Chief, Cleveland Police Department

Dr. Rhonda Williams, Dir, Social Justice Inst, Case Western Res Univ

Moderator: Mark Naymik, Metro Reporter, Cleveland.com

Cleveland and cities across America say they are reinvesting in community policing as a way to rebuild trust between their police departments and the communities they protect. But community policing takes many forms and could take years to make a difference.

We take a look at what Cleveland is already doing, where the department is headed and what it’s learned in the past two years, which have been among the most eventful in the police department’s history.

Tuesday November 15, 2016 7-8:30p.m.

Cost: Free & Open to the Public

Tinkham Veale University Center, CWRU Campus

11038 Bellflower Road, Cleveland OH

Co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University Siegal Lifelong Learning Program, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland, Cleveland.com plus Lakewood and Cuyahoga County Library Systems

Corporate sponsor: First Interstate Properties, Ltd.

Sports Stadium Financing in Cleveland forum Thursday, November 17, 2016

Sports Stadium Financing in Cleveland forum Thursday, November 17, 2016

Panelists:

Len Komoroski, CEO, Cleveland Cavaliers and Quicken Loans Arena

Peter G. Pattakos, Lawyer, sports fan and vocal opponent of the sin tax

Thomas Chema, President, Gateway Consultants Group

Moderator: Peter Krouse, Public Interest and Advocacy Reporter, Cleveland.com

Co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University Siegal Lifelong Learning Program, League of Women Voters-Greater Cleveland, Cleveland.com plus Cleveland Hts/University Hts, Lakewood and Cuyahoga County Library Systems

Corporate sponsor: First Interstate Properties, Ltd.

A Brief History of Religion in Northeast Ohio by George W. Knepper

A Brief History of Religion in Northeast Ohio by George W. Knepper

The link is here

If that link does not work, try this