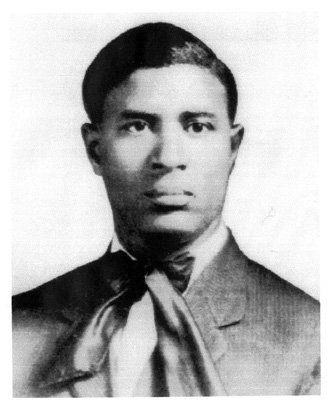

Ohio Historical Society Photo

The pdf is here

INVENTOR GARRETT MORGAN,

CLEVELAND’S FIERCE BOOTSTRAPPER

By Margaret Bernstein

Garrett Morgan was a boundary-pusher and a status-quo smasher.

The son of Kentucky slaves, he moved to Cleveland in 1895, where he would become one of Ohio’s most prolific inventors. His curious mind seemed to crank at breakneck speed at all times, ferreting out problems that needed to be solved and providing the creative spark for his many inventions.

But neither Cleveland nor the nation were ready for a black man operating on such an entrepreneurial level in the early 1900s.

Just like he invented many “firsts,” Morgan himself was a first in many ways as he tried to insert himself and his inventions into the economic mainstream. And as a result, he collided repeatedly with social mores that for centuries had kept blacks in their place.

Persevering in the face of barriers and professional slights, he learned to navigate his way within the tightly segregated confines of 20th century America, although it sometimes meant he had to disguise his race in order to sell his products.

Morgan designed many items, including two life-saving devices – a gas mask that helped firefighters and soldiers survive in suffocating circumstances, and a traffic signal that restored order to intersections that had become chaotic and dangerous after the advent of the automobile.

He even invented institutions that helped nurture Cleveland’s fledgling black middle class. Once Morgan’s products earned him enough income to support his family, he started up a black newspaper, a black businessman’s league and even a black country club.

Decades after his death, it’s not unusual for this black Clevelander to be mentioned prominently during Black History Month, always a time when the achievements of African-Americans are listed and lauded across the nation.

Today he is recognized in his adopted hometown as well. Cleveland has a school, a waterworks plant and a neighborhood square named for the famed African-American inventor.

But these accolades arrived long after he could enjoy them. Although he eventually earned enough to live off his inventions and enjoyed a standard of living experienced by few blacks, he always felt blocked by barriers placed on him because of his race.

——————————

Garrett Augustus Morgan was born in Kentucky on March 4, 1877, the seventh of 11 children.

His parents, both of mixed parentage, had been slaves before the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

His father, Sidney Morgan, was the child of a female slave and a Confederate colonel, John Hunt Morgan. But Sidney Morgan’s father was also his family’s slave owner, and as a result the child suffered great physical abuse from his owners. History books show that this was a common plight for mulatto slaves – their owners would treat them cruelly since they were the physical reminders of an indiscretion on the part of a white man.

“Morgan’s father shared stories of the cruelty and abuse he had suffered, and sought to teach his son about the racial prejudices he would surely have to face in the world,” according to a detailed biographical essay on Morgan that appeared in a 1991 issue of Renaissance magazine.

His mother, Eliza Morgan, was half-Indian and half-black, and reportedly received her maiden name from her slave master. Her father, a Baptist minister, was a spiritual and law-abiding man. His deep and abiding faith would go on to have a big influence in Garrett’s life, giving him patience when he found doors to opportunity slamming in his face.

Young Garrett Morgan attended elementary school in Kentucky and worked on his parents’ farm.

It was a brutal time in Morgan’s native Kentucky, which was still reeling with resentments caused by the abolition of slavery. Lynchings of black men happened frequently in the 1880s and 1890s. Garrett Morgan showed the ambition and independent nature that eventually would make him a wealthy man when he decided, as a teen, that he would leave his family to head north.

At age 14, he arrived in Cincinnati with just a few cents in his pocket. He got a job as a handyman for a white property owner.

Morgan had only attained a fifth grade education while growing up in Claysville, Ky. “He knew how to read. He could write and he could figure,” said his granddaughter, Sandra Morgan of Cleveland, in a 2012 interview.

“But he had higher expectations for himself,” she added. And so he used his earnings as a young teen to hire personal tutors to teach him English and grammar. These competencies, he hoped, would help him get ahead.

Yet young Garrett found that Cincinnati’s racial dynamics did not seem much different from the Jim Crow restrictions of the deep South. A few scattered lynchings had been reported in southern Ohio too, during the years Morgan lived there.

And so he decided to move on. Cleveland seemed as good a place as any to land, since Morgan had some relatives in northern Ohio. He packed up his things and arrived in the area on June 17, 1895. He was one of the earlier blacks to migrate to the area. In 1890, just over 3,000 blacks had been recorded in Cuyahoga County.

Taking a room in a Central Avenue boarding house, Morgan began looking for work. According to Renaissance magazine, his enthusiasm was doused quickly, as he was told over and over, “We don’t employ niggers here.”

He eventually landed a job sweeping floors at Roots & McBride, a sewing machine factory, earning $5 a week. The youth proved to be a quick study, and he had a strong work ethic. He taught himself to sew and to repair sewing machines, and soon started working as a repairman.

Roots & McBride became the setting where his inventor’s spirit took root, and Morgan soon created his first invention — a belt fastener for sewing machines. He sold the idea in 1901 for $150.

In 1907, the Prince-Wolf Company hired him to be their first black machinist. There he met an immigrant seamstress from Bavaria, Mary Hasek. “They would engage in innocent conversations, until Morgan was warned by his supervisor that black men were not allowed to talk to white women in the company. Incensed at being told who he could and could not speak to because of his color, Morgan went to the Personnel Office and quit,” according to Renaissance magazine.

Morgan had been saving his money for years, with a goal of being his own boss. This was the moment, he realized. Using his savings, he rented a building on West Sixth Street and opened a sewing machine repair shop. It was just a few blocks from the Prince-Wolf Co.

These were tough times for African-Americans, but Morgan vowed to make his business a success. He was known to have a motto: “If a man puts something to block your way, the first time you go around it, the second time you go over it, and the third time you go through it.”

While building his business, he also worked hard at another goal: pursuing the seamstress who had caught his eye, Mary Hasek. Although her family refused to accept the interracial relationship, Mary had an independent streak herself and she fell in love with her outgoing and ambitious suitor. The couple married in 1908.

His business had been profitable enough to allow him to build a home at 5204 Harlem Ave. in Cleveland, where he later brought his mother to live, after his father died.

With Mary at his side, Morgan expanded his enterprises. The couple began manufacturing clothing, and developed a line of children’s garments.

Granddaughter Sandra Morgan remembers fondly the beautiful velvet coats with matching muffs that she wore as a little girl, all handmade by Mary. “My party coats, my summer clothes – my grandmother made everything.”

Garrett and Mary’s marriage lasted more than 50 years, until their deaths in the 1960s. Mary came from a big family, but she had little contact with her relatives after she married a black man. She was even excommunicated from her Catholic faith. Sandra Morgan, who still keeps Mary’s rosary and her Bible written in German, believes it hurt her grandmother deeply.

Garrett Morgan didn’t have much contact with his family either after leaving his native Kentucky. For him and his wife, their three children became their world, and they tried to keep their clan closely knit. “I can still remember going to my grandmother’s house, it was sacred. Every Sunday, you were at that house for dinner,” Sandra Morgan said.

And although she was just a young child in 1963 when her grandfather died, she remembers well the values he instilled. “When my grandfather came to Cleveland, he really did work with his hands and worked hard to pull himself up by his bootstraps.”

Her father, Garrett Jr., who pitched in to help his father sell his products, had a similar work ethic and passed that credo down to her: “There’s no slackers in the Morgan family” was a succinct motto they lived by.

At his home near East 55th Street and Superior Avenue, Garrett Morgan Sr. spent hours tinkering in his workshop, trying to come up with solutions to common problems. Around 1910, he had been working on a way to ease the scorching caused by a sewing machine’s rapid movement against wool, when he stumbled into a valuable discovery.

It happened by accident, when Morgan wiped his hands on a cloth after experimenting with a lye-based solution in his workshop.

Later, he noticed the woolen fibers had gone from crinkly to straight. Curious to see if he could replicate the result, Morgan experimented on a neighbor’s Airedale dog, and eureka: G.A. Morgan’s Hair Refining Cream was born.

It was the first product ever shown to chemically straighten kinky black hair – a forerunner to the popular hair relaxers of today — and Morgan shrewdly deduced its potential marketability. To go along with it, he developed a comprehensive line of hair care products, from his Hair-Lay-Fine Pomade that “makes unruly hair lay where you want it” to a special pressing comb for “heavy hair.” Morgan called his hair products “the only complete line of hair preparations in the world,” and soon he had a thriving business shipping the items to drugstores across the country.

He did whatever he thought it took to market his hair products. At one point, Morgan purchased a calliope and positioned the steam-powered organ inside a bus. He and son Garrett Jr. would blast the calliope loudly as they drove through Cleveland neighborhoods, attracting attention from people on the street whom they would then direct to drugstores that sold their creams and other items.

Around the same time, he was also working on “safety helmet” that he first developed in 1912. His intent, Morgan once wrote, was to invent an apparatus that could “provide a portable attachment which will enable a fireman to enter a house filled with thick suffocating gasses and smoke and to breathe freely for some time therein, and thereby enable him to perform his duties of saving lives and valuables without danger to himself.”

Morgan had long been aware of the fire hazard posed by wooden shanty houses like the ones in some areas of Cleveland and also in his rural Kentucky hometown. A fire could race through these homes in an instant, giving occupants barely seconds to get out. Morgan sometimes joked that that these homes went up in flames so quickly that the first thing to burn would be the fire bucket. But he was serious about the need to devise a solution.

In 1914, he patented his version of the gas mask. His safety hood had two tubes that extended to the floor, where Morgan assumed that fresh air was most likely to be found in case of fire. His device included a backpack of unpressurized reserve air.

Always quick to seek ways to sell his products after obtaining patents, Morgan traveled the nation after 1914 to demonstrate his device to fire departments. Knowing fire departments in the South would have no interest in enriching a black inventor, Morgan hired a white actor to pose as the inventor while Morgan dressed up as an Indian chief in New Orleans during a demo at the International Association of Fire Chiefs. During their schtick, the actor would announce that “Big Chief Mason” would don the mask and go inside a smoke-filled tent for 10 minutes. The audience was stunned when Morgan emerged unharmed after 15 minutes in the suffocating tent, and orders began to flow.

He had disguised his identity previously in 1911, when his mask won an award at the New York Safety Exposition. Again, he sent a white actor to accept the honor. “It was a little bittersweet that he couldn’t accept his own award,” said his granddaughter. “He couldn’t claim credit for his own work.”

Yet Morgan’s strategy paid off, literally. Mine owners and fire departments from across the United States and Europe began purchasing the hoods, and the U.S. Army used a slightly redesigned version of the Morgan mask during World War I.

The mask would endure a huge test in Morgan’s adopted hometown of Cleveland, when a group of miners was injured in a shaft under Lake Erie on July 25, 1916. An explosion had torn through an underwater tunnel, trapping more than a dozen men in an area filled with smoke and gas.

Morgan’s phone rang at 3 a.m. in the morning, summoning him to the scene. Still in his night clothes, he rushed to the lake with his safety hoods, bringing along his brother Frank and a neighbor.

Although rescue accounts differ, it is believed that his rescue team brought six men back to the surface and saved their lives, proving the hood’s effectiveness.

But the inventor’s heroism resulted in more slights. The Carnegie Hero Commission declined to recognize the Morgan rescue as an act of bravery. Even Morgan’s request for the city of Cleveland to help him with his medical bills, after he encountered noxious smoke in the waterworks tunnels, was unsuccessful.

Morgan’s granddaughter said her family also believes that sales of the gas mask began to drop as news traveled the nation that the inventor was a black man. “As far as I know, they were selling very well until it was discovered that the patent holder was black, and then sales dried up. That was very upsetting for him.”

Morgan, who had moved to Cleveland in search of opportunities denied to black men in the South, was clearly disappointed, Sandra Morgan said. He wanted nothing more than to be known as a “black Edison,” he told his family.

What he craved wasn’t the fame enjoyed by Thomas Edison, known nationally as “the Wizard of Menlo Park.”

Morgan wanted to live without limits, to be fairly remunerated for his many innovations and create a business empire as Edison had done. It disturbed him that he wasn’t afforded that chance. Of course, few inventors reached the heights achieved by Edison – it wasn’t just race that kept Morgan from following in his footsteps.

But opening doors closed to blacks had been a priority for Morgan throughout his life. A fervent bootstrapper, he believed strongly in doing all he could to strengthen Cleveland’s black community. In 1920, Morgan started a newspaper, the Cleveland Call, the predecessor to Cleveland’s Call & Post. Even this decision was a stab at righting a wrong against blacks. At the time, blacks weren’t allowed to advertise in white papers, and also reporting about blacks was considered negative and stereotypical.

By that time, Morgan had become a wealthy business owner with dozens of employees.

Automobiles were just becoming popular with the masses, and Morgan is believed to be one of the first black men in Cleveland to own one. From then on, “He always loved sweet-looking rides,” his granddaughter recalled with a laugh.

At the time, cars and horse-drawn buggies were all competing with pedestrians for space on Cleveland’s crowded streets. Morgan realized a device to control the haphazard traffic was needed, and devoted himself to inventing a solution.

On Nov. 20, 1923, he received a patent for the invention for which he’s best known: the traffic signal.

Although many say Morgan invented the traffic light, that is not technically true. There were no lights on Morgan’s device.

Morgan’s manually operated signal was mounted on a T-shaped pole. It gave people approaching an intersection three choices: stop, go or stop in all directions (which halted cars and buggies so that pedestrians could move safely).

General Electric, realizing the necessity for Morgan’s invention, purchased the patent from him for $40,000.

In 1923, he used some proceeds from sale to purchase a large piece of property near Wakeman, Ohio. There he created Ohio’s first black country club – a place where middle-class blacks could enjoy recreation like horseback riding, fishing and horseshoes. “The all-black facility, however, was not wanted in the area by local whites,” reported Renaissance magazine, which said that Klan members rode onto the property one night and burned a cross.

“Morgan and his brothers ran the m off with guns and warnings of their own. The KKK never returned, and the club enjoyed uninterrupted success until Morgan lost the bulk of his money in the 1929 stock market crash. With a freeze on his savings account, Morgan wisely sold 200 acres of the Wakeman land to pay the taxes on the remaining 200.”

Morgan died in 1963. The city of Cleveland never did grant his request for pension benefits in light of injuries sustained in the 1916 rescue.

Sandra Morgan said her family still has a letter that Morgan sent to Cleveland mayor Harry Davis expressing anger that he wasn’t compensated after the waterworks disaster. “I’m not an educated man, but I have a Ph.D from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment,” it began.

Did he die a bitter man? Sandra Morgan thinks not. Her grandfather had expressed disappointment many times over, but just as he tirelessly tested his inventions, Garrett Morgan took pride in surviving test after test of his mettle. The sale of the traffic signal had put him in a position where he didn’t have to work for anyone else any more, leaving him free to pursue the things that interested him most. And with that freedom came a sense of peace, she believes.

His headstone at Lakeview Cemetery reads simply: “By his deeds, he shall be remembered.”

And in 1991, 28 years after his death, one of his most heroic deeds — saving lives that seemed doomed in the underwater tunnel beneath Lake Erie — was remembered and recognized. The city of Cleveland finally honored Morgan by renaming its lakefront waterworks plant for him.

For more on Garrett Morgan, click here