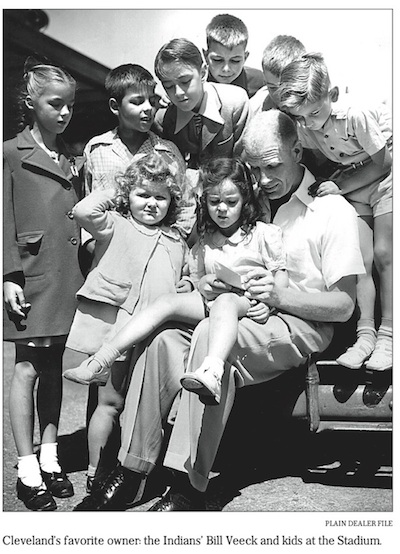

Bill Veeck. The Man Who Conquered Cleveland and Changed Baseball Forever.

By Bill Lubinger

The morning of Oct. 12, 1948, was chilly and battleship gray.

But the city of Cleveland may have never felt so glorious; its residents never so proud.

Estimates vary. Some say more than 300,000 fans jammed the sidewalks of Euclid Avenue, from Public Square to University Circle. Others put the number closer to 500,000.

They lined the city’s main artery, squeezing parts of the two-lane thoroughfare down to one, all to celebrate their championship baseball team.

The Indians had finally won a World Series championship – their first since 1920 and, as the cruel baseball Gods would have it more than six decades later, their last.

Convertibles carrying the Indians’ players and their wives and city leaders paraded the 107 blocks past a cheering throng.

“I remember getting off a train and riding in an open car down Euclid Avenue at 8 o’clock in the morning,” recalls Al Rosen, one of only three players from that team still living. “The town lined up on either side of the street. It was remarkable. The people turned out en masse.”

Teammate Eddie Robinson, now 91 and retired in Fort Worth, Texas, still remembers how the sidewalk crowds were elbow to elbow. Some revelers perched themselves on parked cars and buses.

“It was wonderful,” he says. “It was a wonderful year.”

A year largely orchestrated by a chain-smoking man in the lead car with reddish hair, a wooden leg from a World War II injury and a huge smile that matched his gregarious personality.

No, not Indians’ 31-year-old shortstop/manager and World Series hero Lou Boudreau. Not Cleveland Mayor Tom Burke. But team owner Bill Veeck, who left an indelible mark on Cleveland and Major League Baseball.

“Maverick” is the term biographers and others still use to describe him, because he had the strength and conviction to follow his own path despite insults and criticism from traditionalists.

While other team owners scoffed and ridiculed him for what they considered low-brow publicity stunts, Veeck introduced many of the fan-friendly promotions that still make heading to the ballpark an experience that transcends the playing field.

In keeping with his own social conscience, he signed the American League’s first African-American player and continued as a pioneer in civil rights activism throughout his career.

And, of course, it was under his stewardship that Cleveland Indians’ fans last reveled in a world title.

“I think winning the World Series put Cleveland on the map,” Robinson says. “I think Bill Veeck and the stuff that he did during the year, all the promotions he had, I think Cleveland became super big-league in a hurry.”

Cleveland celebrated a baseball champion that fall day, but it also celebrated itself.

The city was a much different place back then. Vibrant. Nationally respected. And much, much bigger.

Cleveland, named an All-America City for the first time in 1949, was also a burgeoning industrial force at the time, built on shipping, automotive and iron and steel before the decline began in the 1960s. With more than half of the North American population within 500 miles of Public Square, Cleveland was considered prime real estate.

But if the baseball championship was what truly defined the city as “big league,” then William Louis Veeck Jr. was the creative mind that wrote and directed the script.

*****

Veeck wound up in Cleveland by way of Chicago, where he was born and grew up in a baseball-happy family. (William Veeck Sr. was a former sports writer who built the Chicago Cubs into pennant winners in the early 1930s.)

Veeck desperately wanted to own a major-league team and apparently came within 24 hours of landing the Pittsburgh Pirates.

According to Paul Dickson’s biography, “Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick,” the Pirates’ $2 million asking price was too high. So Veeck set his sights on Cleveland, which was considered a better business location because it wasn’t as dependent on one industry – in Pittsburgh’s case, steel.

Weeks before buying the Indians, Veeck did his homework, taking cabs and streetcars around the city, talking to people in restaurants, bars and social clubs for feedback on the team and their ballpark experiences.

Veeck discovered, Dickson writes, that Clevelanders loved their team but not the group that had owned it since 1928. He was stunned to learn that balls hit into the stands had to be thrown back, that games weren’t broadcast on the radio and that most cab drivers and bartenders had no idea when the Indians were playing in town.

With that as the backdrop, Veeck, on June 22, 1946, got an investor group comprised mainly of Chicago bankers – but also included comedian Bob Hope – to buy the Indians for $1.54 million.

For some perspective, Forbes magazine recently estimated the Indians’ franchise value at more than $400 million. And that $1.5 million for the Tribe in the post-war era? That might buy a team a very low-level free agent today.

The Indians were a fifth-place team the season before. Between that weak finish and the team’s obvious marketing void, Veeck had much work to do. He got right to it.

Veeck talked to fans and, more importantly, he listened to his customers. To draw more fans to the ballpark, no detail was too small.

He added mirrors to the ladies’ rooms when he found out there weren’t any. He often sat in the bleachers with the common fans. When he discovered the ballpark announcer couldn’t be heard clearly way out there, he had the sound system fixed.

Within weeks of buying the team, games began being broadcast on radio. He added special ladies’ days, enticing them with free hard-to-get nylons or orchids imported from Hawaii. He had National League scores posted in the ballpark, added clerks to make it easier to order tickets by phone, spiffed up the stadium ushers in uniforms and polished shoes, ran game-day buses to and from rural areas and paid special attention to the stadium food, especially the hot dogs, peanuts and mustard.

In-game entertainment and post-game fireworks became staples of the Veeck-led version of Major League Baseball, just as they are today.

Veeck also made himself available to any group that needed a luncheon or dinner speaker – and not just in Cleveland, but regionally, from Erie to Buffalo to Cincinnati.

He schmoozed the media and was even more gracious with fans, listing his home number in the phone book and often standing outside the ballpark gates to thank them as they left. He was a player-friendly owner who even threw batting practice at times.

As his plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., reads, Veeck was “a champion of the little guy.”

All along, Veeck fielded criticism from fellow major-league owners who took shots at him. Baseball was serious business, the national pasttime, not a circus sideshow. (As owner of the St. Louis Browns, he once sent a midget to the plate to draw a walk.)

But fans loved it.

Once the Indians moved all their home games to massive Municipal Stadium (where Cleveland Browns Stadium now stands), the turnstiles spun. Previously, the team had played at 22,500-seat League Park on the city’s East Side and in the 78,000-seat Municipal Stadium only on weekends, holidays and when larger crowds were expected.

In 1946, the club finished sixth but drew more than a million fans for the first time in team history.

Veeck and his team also made history in 1947 by signing Larry Doby from the Negro Leagues’ Newark Eagles, making him the first African-American in the American League. It was just 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers became baseball’s first black player.

Many major-league owners railed against teams hiring black players because they had their own self-interest to protect. Negro League teams rented their ballparks. As black stars moved from the Negro Leagues to the big leagues, the Negro League games drew fewer fans, generating less rental income for the ballpark owners.

Former teammate Eddie Robinson believes Doby, who wrestled with the same racism and for-whites-only segregation, didn’t get the recognition he deserved because Jackie Robinson was the first.

“Doby handled himself well,” says Eddie Robinson, who lived in a Rocky River apartment when he played for the Indians. “He took the jabs and all from the visiting players and the fans, and went right along and did his work just like (Jackie) Robinson did.”

(“It wasn’t very pleasant being a Jew at the same time, either,” says Al Rosen.)

By the time he retired from baseball, Doby, who died in 2003, was a seven-time All-Star outfielder who spent 10 of his 13 major-league seasons in Cleveland.

Larry Doby Jr. was born after his father was through playing, so his impressions are based on stories his dad told him.

While some teammates refused to shake his hand when he was introduced, there were others, such as Bob Lemon, Jim Hegan and Joe Gordon, “who didn’t care where he came from or what color his skin was,” says Doby Jr.

“It was tough, but there were a lot of good guys who reached out to him and made the tough times not so tough.”

Eddie Robinson also remembers Doby being generally well-accepted by the team.

“Well, there was some southern boys, of course, if you were from the South and they were bringing up a black guy on to the team,” he says, “it was something different.”

Eddie Robinson, as his thick drawl reveals, was one of those southern boys. He admits to having to adjust to a black man in the clubhouse.

“Well, it bothered me just like it bothered everybody else,” he says. “It was something that was going to happen, so you sucked it up and went along with it and it turned out to be very good.”

What troubled Robinson more was that Boudreau replaced him with Doby in the lineup just two days after the manager reassured him he was the team’s first baseman.

“That’s how it bothered me most,” he says.

Doby lived with a family in Shaker Heights for part of his time in Cleveland. Although the city was – and largely remains – racially-divided, Doby was welcomed by Northeast Ohio, according to his son.

“I’m going to tell you what he told me,” says Doby Jr. “My father was the kind of guy who didn’t talk about the past much, but here’s what he told me about Cleveland. He said he never got booed there, ever. So that, to me, sums up what he felt about that city and what that city felt about him.”

When the 1947 season ended, the Indians had improved to fourth place and drew 1.5 million fans – second most in the league. Veeck continued to put the pieces together both on and off the field.

“Bill was a great showman,” Rosen says. “Probably the best that baseball’s ever known.”

And the great showman’s biggest show was about to arrive.

The 1948 Indians featured five future Hall of Famers: pitchers Bob Feller, and Lemon, Doby in the outfield, Joe Gordon, a second baseman the Indians obtained from the New York Yankees in a trade, and Boudreau, the shortstop/manager. The team also acquired Gene Bearden, an unheralded knuckleballer who would become the team’s World Series hero.

About midway through the season, Veeck, in another controversial move, would add a sixth future Hall of Famer.

The Indians needed an effective reliever. Veeck’s solution was 42-year-old Satchell Paige, a star of the Negro Leagues who was signed by the Indians on his birthday.

Again, Veeck was criticized. Just another cheap publicity stunt to sell tickets, other owners claimed.

But Veeck’s commitment to civil rights was genuine and deep-rooted. He had joined the NAACP after arriving in Cleveland, according to Dickson’s memoir, and appeared in an NAACP recruiting poster with Doby and Paige.

By the time he sold the Indians after the 1949 season for $2.2 million, Veeck had integrated every level of ballpark operations, from security to ushers to vendors and the front office. In fact, he had hired Olympic gold medal-winner Harrison Dillard in the team’s public relations office.

Fans filled the ballpark, but not because Paige was an over-the-hill freak show with the crazy windup, high leg kick and something he called a “hesitation pitch.” Paige went 6-1 down the season’s stretch run, including a 1-0 three-hitter over Chicago in front of a record night-game crowd of 78,382.

The Indians wound up tied for first with the Boston Red Sox, resulting in a one-game playoff at Fenway Park. The Tribe took that one, 8-3, to advance to the World Series against the National League’s Boston Braves.

Veeck’s Indians beat the Braves in six games. Doby became the first black man to homer in a World Series. And Game Five, in Cleveland, drew a record 86,288 fans.

The Indians drew 2.6 million fans that season, a major-league record that stood for 14 years.

“The team began to play well and (the players) believed in themselves,” says Rosen, who got called up from the minors late that season and played behind third baseman Ken Keltner. “It was all very magical, and when someone reminds of it I get chills.”

Major League Baseball has expanded to more cities. Players, who once took part-time jobs in the offseason to help pay the bills, are now extremely well paid, to the point where securing other work isn’t necessary.

Although some of the rules have changed, the game is relatively the same. But fans experienced their Tribe much differently from their family rooms.

Now, all but a few Indians’ games are broadcast on television. Fans can watch every inning of an entire season in their living room if they so choose. No so in 1948. The first telecast by Ohio’s first TV station (WEWS) didn’t occur until 1947. So televised Indians’ games were rare.

“It was all radio,” remembers Carl Parise of Mayfield Heights, describing what it was like to hear announcers Jack Graney and Jimmy Dudley call the games.

“You’d be listening to them on the radio, they’d have you up out of your seat. They were just great,” says Parise, who was 8 years old when the Tribe last won a World Series. “You’ve got to remember, if you were sports fans back then, you were spoiled. The Browns and Indians were winners.”

As was Cleveland – largely because of a fun-loving, risk-taking, marketing genius named Veeck.

To read more about Bill Veeck and the 1948 Cleveland Indians, click here