Communications/Media/Journalism Links from Encyclopedia of Cleveland

– COMMUNICATIONS –

ACTIVE COMMUNICATIONS, INC.

ADDISON, HIRAM M.†

ADVANSTAR COMMUNICATIONS

ALBURN, WILFRED HENRY†

ALEXANDER, WILLIAM HARRY†

ALIENED AMERICAN

AMERICKE DELNICKE LISTY

AMERISKA DOMOVINA

AMERITECH (AMERICAN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES CORP.)

ANDERSON, ERNIE†

ANDORN, SIDNEY IGNATIUS†

ANDRICA, THEODORE†

ARMSTRONG, WILLIAM W.†

ASHMUN, GEORGE COATES†

BAKER, ELBERT H.†

BALDWIN, SAMUEL PRENTISS†

BANDLOW, ROBERT†

BANG, EDWARD F.†

BEAUFAIT, HOWARD G.†

BELL, ARCHIE†

BELLAMY, PAUL†

BELLAMY, PETER†

BENEDICT, GEORGE A.†

BERGENER, ALBERT EDWARD MYRNE (A.E.M.)†

BIGHAM, STELLA GODFREY WHITE†

BLACK, HILBERT NORMAN†

BLODGETT, WALTER†

BLUE, WELCOME T. , SR.†

BODDIE RECORDING CO.

BOHM, EDWARD H.†

BONE, JOHN HERBERT ALOYSIUS (J.H.A.)†

BRASCHER, NAHUM DANIEL†

BRIGGS, JOSEPH W.†

BROWNE, CHARLES FARRAR [ARTEMUS WARD, PSEUD.]†

BUSINESS & PROFESSIONAL WOMEN’S CLUB OF GREATER CLEVELAND (BPW)

BYSTANDER

CANKARJEV GLASNIK

CARROLL, GENE†

CATALYST: FOR CLEVELAND SCHOOLS

CATHOLIC UNIVERSE BULLETIN

CATTON, BRUCE†

CHANDLER, NEVILLE (NEV) ALBERT JR.†

CLEAVELAND GAZETTE & COMMERCIAL REGISTER,

CLEVELAND ADVERTISER

CLEVELAND ADVERTISING CLUB

CLEVELAND ADVOCATE

CLEVELAND BLUE BOOK

CLEVELAND CALL & POST

CLEVELAND CITIZEN

CLEVELAND DAILY ARGUS

CLEVELAND DAILY GAZETTE

CLEVELAND DAILY REVIEW

CLEVELAND EDITION

CLEVELAND FREE TIMES

CLEVELAND FREENET

CLEVELAND GATHERER

CLEVELAND GAZETTE

CLEVELAND HERALD

CLEVELAND HERALD AND GAZETTE

CLEVELAND JOURNAL

CLEVELAND JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME

CLEVELAND LEADER

CLEVELAND LIBERALIST

CLEVELAND LIFE

CLEVELAND MAGAZINE

CLEVELAND MESSENGER

CLEVELAND NEWS

CLEVELAND NEWSPAPER GUILD, LOCAL 1

CLEVELAND NEWSPAPER STRIKE OF 1962

CLEVELAND PRESS

CLEVELAND RECORD

CLEVELAND RECORDER

CLEVELAND RECORDING CO.

CLEVELAND REPORTER

CLEVELAND REPUBLICAN

CLEVELAND SHOPPING NEWS

CLEVELAND SUNDAY SUN

CLEVELAND SUNDAY TIMES

CLEVELAND TIMES (1845)

CLEVELAND TIMES (1922)

CLEVELAND TODAY

CLEVELAND TOWN TOPICS

CLEVELAND UNION LEADER

CLEVELAND WHIG

CLEVELAND WORLD

CLEVELANDER

CLIFFORD, LOUIS L.†

CLOWSER, JACK†

COBBLEDICK, GORDON†

COLLINS, JAMES WALTER†

COMBES, WILLARD WETMORE†

COMMERCIAL INTELLIGENCER

COVERT, JOHN CUTLER†

COWGILL, LEWIS F.†

COWLES, EDWIN W.†

DAILY CLEVELANDER

DAILY FOREST CITY

DAILY GLOBE

DAILY LEGAL NEWS

DAILY MORNING MERCURY

DAILY MORNING NEWS

DAILY NATIONAL DEMOCRAT

DAILY TRUE DEMOCRAT

DAVY, WILLIAM MCKINLEY†

DAY, WILLIAM HOWARD†

DENNICE NOVOVEKU

DEUBEL, STEFAN†

DIETZ, DAVID†

DIRVA

DONAHEY, JAMES HARRISON†

EAGLE-EYED NEWS-CATCHER

ELWELL, HERBERT†

ENAKOPRAVNOST

EXAMINER

FAIST, RUSSELL†

FETZER, HERMAN†

FINE ARTS MAGAZINE

FISHER, EDWARD BURKE†

FISHER, EDWARD FLOYD†

FOREST CITY PUBLISHING CO.

FORTE, ORMOND ADOLPHUS†

FREED, ALAN†

FRENCH, WINSOR†

FULDHEIM, DOROTHY†

GAYLE, JAMES FRANKLIN†

GEORGE R. KLEIN NEWS CO.

GERMANIA

GOMBOS, ZOLTAN†

GRANEY, JOHN GLADSTONE†

GRAY, JOSEPH WILLIAM†

GRILL, VATROSLAV J.†

GUTHRIE, WARREN A.†

HALLORAN, WILLIAM L.†

HANNA, DANIEL RHODES†

HANNA, DANIEL RHODES, JR.†

HARRIS, JOSIAH A.†

HAYES, MAX S. (MAXIMILIAN SEBASTIAN)†

HEINZERLING, LYNN LOUIS†

HERRICK, MARIA M. SMITH†

HEXTER, IRVING BERNARD†

HLAVIN, WILLIAM S.†

HOLDEN, LIBERTY EMERY†

HOPWOOD, AVERY†

HOPWOOD, ERIE C.†

HOVORKA, FRANK†

HOWARD, NATHANIEL RICHARDSON†

HOYT, HARLOWE RANDALL†

INDEPENDENT NEWS-LETTER

INGALLS, DAVID S., SR.†

JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS AND ART CRITICISM

KELLY, GRACE VERONICA†

KENNEDY, CHARLES E.†

KENNEDY, JAMES HENRY†

KOBRAK, HERBERT L.†

KOHANYI, TIHAMER†

KUEKES, EDWARD DANIEL†

KURDZIEL, AUGUST JOSEPH†

L’ARALDO

LA VOCE DEL POPOLO ITALIANO

LATINO

LEWIS, FRANKLIN ALLAN “WHITEY”†

LOEB, CHARLES HAROLD†

LORENZ, CARL†

LOVELAND, ROELIF†

MACAULEY, CHARLES RAYMOND†

MANNING, THOMAS EDWARD “RED”†

MANRY, ROBERT N.†

MARKEY, SANFORD†

MARSH, W. WARD†

MCAULEY, EDWARD J.†

MCCARTHY, SARA VARLEY†

MCCORMICK, ANNE (O’HARE)†

MCDERMOTT, WILLIAM F.†

MCLAUGHLIN, RICHARD JAMES†

MCLEAN, PHIL†

MODERN CURRICULUM PRESS, INC.

MONITOR CLEVELANDSKI

MOORE, GEORGE ANTHONY†

MOTHERS’ AND YOUNG LADIES’ GUIDE

MUELLER, JACOB†

MYERS, PIERRE (PETE, “MAD DADDY”)†

NEW CLEVELAND CAMPAIGN

NEW DAY PRESS

NEWBORN, ISSAC (ISI) MANDELL†

NEWMAN, AARON W.†

NORTHERN OHIO LIVE

NOVY SVET

OHIO AMERICAN

OHIO CITY ARGUS

OTIS, CHARLES AUGUSTUS, JR.†

PANKUCH, JAN†

PEIXOTTO, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN†

PENFOUND, RONALD A. (CAPTAIN PENNY)†

PENTON MEDIA

PENTON, INC.

PERKINS, ANNA “NEWSPAPER ANNIE”†

PERKINS, MAURICE†

PETERS, RICHARD DORLAND†

PLAIN DEALER

PLAIN PRESS

POINT OF VIEW

PORTER, PHILIP WYLIE†

PRESS CLUB OF CLEVELAND

PRINT JOURNALISM

PRINTING AND PUBLISHING IN CLEVELAND

RAPER, JOHN W.†

ROBERTS, WILLIAM (BILL) E.†

ROBERTSON, CARL TROWBRIDGE†

ROBERTSON, DONALD Q. “DON”†

ROBERTSON, GEORGE A.†

ROBERTSON, JOSEPHINE (JO) WUEBBEN†

ROBINSON, EDWIN†

ROCKER, SAMUEL†

ROGERS, JAMES HOTCHKISS†

SCENE

SCRIPPS, EDWARD WILLIS†

SELTZER, LOUIS B.†

SIEDEL, FRANK†

SIEGEL, RICHARD H.†

SILHOUETTE

SILVER, DON†

SMEAD, TIMOTHY†

SMITH, HARRY CLAY†

SMITH, HERALD LEONYDUS†

SNAJDR, VACLAV†

SOCIAL REGISTER

SPERO, HERMAN ISRAEL†

STAGER, ANSON†

STASHOWER, FRED P.†

STEMPUZIS, JOSEPH†

STOKES, CARL B.†

STRASSMEYER, MARY A.†

SUN NEWSPAPERS

SUNDAY POST

SUNDAY STAR

SUNDAY VOICE

SVET-AMERICAN

SVOBODA, FRANK J.†

SZABADSAG

TELEGRAPHY AND TELEPHONES

TELEVISION

TELLO, MANLY†

THIEME, AUGUST†

THORNTON, WILLIS†

TIME

UNDERGROUND PRESS

VAIL, HARRY LORENZO†

VAIL, HERMAN LANSING†

WAECHTER UND ANZEIGER

WALKER, WILLIAM OTIS†

WCLV

WCPN

WEIDENTHAL, LEO†

WEWS (Channel 5)

WEY, ALEXANDER JOSEPH†

WGAR

WHAT SHE WANTS

WHITE, STELLA GODFREY†

WHK

WIADOMOSCI CODZIENNE

WICAL, NOEL†

WICKHAM, GERTRUDE VAN RENSSELAER†

WIDDER, MILTON “MILT”†

WIESENFELD, LEON†

WILLIAM FEATHER CO.

WJMO†

WJW-TV (Channel 8)

WKYC (Channel 3)

WMMS

WOLF, FREDERICK C.†

WRESTLING

WRMR

WVIZ (Channel 25)

WWWE

WZAK

YIDDISHE VELT

Gladys Haddad speaks about Flora Stone Mather

Speech given by Gladys Haddad in 2007 author of “Flora Stone Mather: Daughter of Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue and Ohio’s Western Reserve”

The Civic Revival in Ohio – Dissertation by Robert Bremner (full download)

The complete doctoral dissertation written by Robert H. Bremner, The Ohio State University in 1943

Be patient, the document will take a few minutes to download.

The download is here (approx 45mg)

A History of the Karamu Theatre of Karamu House, 1915-1960

A history of the Karamu Theatre of Karamu House, 1915-1960

Doctorate thesis by Reuben A. Silver, Ohio State University, 1961

554 pages, download is approx 48mg (so be patient)

News Aggregator Archive 3 (4/24/12 – 6/30/12)

The Great Lakes Region Played a Key Role in the War of 1812, and You Can Visit Several Important Sites (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Health-Law Reaction Draws Fire (Toledo Blade)

Ohio Faces Medicaid Decision After Health Care Ruling (Dayton Daily News)

Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s Adminstration Wrestles With Health Care Ruling, Considers Next Steps (Plain Dealer)

Cuyahoga Community College Seeking Out-of State Students for Online Degree Program (Plain Dealer)

Political Battle Over Health Care Looms For Ohio (San Francsco Chronicle)

Sprawl Costs Regional Households and Economy, Sustainability Report Shows (Plain Dealer)

Cleveland Developers Win Tax Credits to Bring 111 Apartments Downtown (Plain Dealer)

Mayfield Heights Rejects Cuyahoga County’s Anti-Poaching Agreement (Sun News)

Ohio, Ky. May Consider Get-Tough Immigration Laws (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Homes, Museums of Presidents Garfield, Hayes and McKinley in Ohio Recall Their Era (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

United Execs Laud Efforts to Back Local Hub (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Ohio Has Role In Healthcare Reform (Chillicothe Gazette)

Portman Squarely in the Spotlight These Days (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Cities Invest Big in River Plans (Dayton Daily News)

Let Cleveland Metroparks Run the Lakefront Parks: Editorial (Plain Dealer)

Cleveland’s Lakefront Parks Have Problems That Go Beyond Trash and Weeds: Mark Naymik (Plain Dealer)

Cleveland’s State-Run Lakefront Parks are Embarrassing: Mark Naymik (Plain Dealer)

New Beachwood Law Will Put Points on Driver’s Licenses for Motorists Caught Using Cellphones (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Win Critical for Obama and Romney (Washington Post)

Drought Worries Growing in Ohio (Columbus Dispatch)

Downtown Cleveland Remains a Major Employment Center (Plain Dealer)

New Orleans’ Effect on Newspapers (Youngstown Vindicator)

New Orleans Times-Picayune Cuts Half of Newsroom Staff (Business Week)

Ohio Gains 19,600 Workers Thanks to Boost from Rebounding Auto Sector, Among Others (Columbus Dispatch)

From Waste to Watts: Cleveland’s Controversial Pursuit of Trash Collection Technology (Plain Dealer)

Two Ohio Cities Hold Key to Who Carries State in November (Los Angeles Times)

Surprise! Ohio Colleges Among the Most Expensive (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Clinical Trials Boost Economy in Ohio (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland Public Library’s TechCentral Offers Users Advanced Technology (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Hydrogen Fuel-Cell Makers Poised for Boom Times (Lima News)

Ohio University to Open Medical School Branch in Warrensville Heights (Columbus Dispatch)

Sheep Serve as Lawn Mowers in Cleveland (Ohio News Network)

NPR Celebrates a Revitalized Downtown Cleveland (Cleveland Scene)

Special Interest Groups Outside of State Pumping Money Into Ohio (Dayton Daily News)

War of 1812: Culmination of 20 Years of Conflict Opened Up the Future of Ohio – Elizabeth Sulivan (Plain Dealer)

Established Locally, Some Restaurateurs Looking Beyond NE Ohio (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Ohio Doubles Film Incentive (Variety)

TravelCenters of America, Shell to Add 200 Natural Gas Fueling Lanes to Truck Stops Along Highways (Plain Dealer)

“Endangered” Designation Couple Spare Zoar Village–One of Ohio’s Historic Treasures (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland’s 2nd Inner Belt Bridge Could Be Built 7 Years Earlier Than Expected (Plain Dealer)

Cincinnati Comes Back to Its Ohio River Shoreline (NewYork Times)

Farmers Markets in Northeast Ohio Swing into Full Season (Plain Dealer)

The Price of Pay-To-Play. As Sports Fees Rise, More Students Forced to Sideline (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Teen Job Prospects Brighten Dramatically (Plain Dealer)

Kasich Signs Lake Erie Water Bill (Toledo Blade)

Cuyahoga County Offers Services in Pursit of Regionalism (Plain Dealer)

Removal of Billions of Gallons of Water from the Earth’s Surface Arouses New Opposition to Fracking (Akron Beacon Journal)

Remembering Cleveland’s Muhammad Ali Summit, 45 Years Later (Plain Dealer)

Farmers and Shoppers Unite to Create Year-Round Market for Local Food (WKSU News)

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson’s Feat of Statesmanship Wins Admiration – Brent Larkin (Plain Dealer)

Instead of Heading to College, 3 Northeast Ohio Graduates Take Roads Less Traveled (Plain Dealer)

Kasich Signs Texting-While-Driving Ban Into Law (Columbus Dispatch)

Shale Gas Boom Could Bring Manufacturing Jobs Back to U.S., Economists Say (Plain Dealer)

Proposal Would Allow Driver’s Ed Classes to be Taken Online (WVIZ/WCPN Ideastream)

Federal Government Waives No Child Left Behind Standards For Ohio (Plain Dealer)

Federal Waiver in Hand, State to Get Tough Evaluating Schools (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio White Working-Class Voters: On the Fence (Reuters)

On Memorial Day, Clevelanders Observe the 200th Anniversary of War of 1812 Outbreak (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Lawmakers Approve New Oil and Gas Regulations (Plain Dealer)

Beachwood Approves Goat Ordinance (Cleveland Jewish News)

House Fracking Bill Reworked (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Start-Up to Bring Gigabit Broadband to Six U.S. Communities (LA Times)

Ohio Senate Passes Water Use Bill Easily, Gov John Kasich Will Sign It (Plain Dealer)

Siemens Energy Interested in Lake Erie Wind Turbine Project (Plain Dealer)

Cuyahoga County Council Debates Casino Revenues (Plain Dealer)

We Are Ohio Pushes for Redistricting Reform (Columbus Dispatch)

Campaign Contributions From Employees of Canton Firm Under Investigation (Columbus Dispatch)

Eaton Corp. Plans to Merge with Ireland’s Cooper Industries on a $11.8 Billion Deal (Plain Dealer)

American Greetings Details Headquarters Plan, Says Westlake Construction to Start in Early 2013 (Plain Dealer)

The Battleground: Ohio’s New Politics of Class, Money and Anger (New Republic)

Cleveland Student David Boone Worked Hard to Go From Homeless to Harvard (Plain Dealer)

Rural Ohio Poor Face Unique Challenges (Toledo Blade)

Higbee Building Lives Again as Cleveland Bets on Casino (Toledo Blade)

Ohio’s Unemployment Rate at Lowest Since October 2008 (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland’s RTA Joins NASA to Test Bus Powered by Hydrogen Cells (Plain Dealer)

A Pause in Ohio’s Gas Boom as Chesapeake Energy Struggles (Plain Dealer)

Pepper Pike to Move Dispatch to Beachwood as Early as July (Sun News)

Statewide Texting Ban, Teen Rules Sent to Ohio Governor (NewsNet 5)

Warm Spring Weather Could Spur June Algae Outbreaks (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Driving Classes May Go Online (Dayton Daily News)

The Long Class War in Cleveland – Roldo Bartimole (Cleveland Leader)

Fracking: A Rush to Riches. A Special Report (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Undergraduate Chinese Students Enrolling in Ohio Colleges in Record Numbers (Plain Dealer)

Healthcare Jobs Lift Pittsburgh From Recession (Los Angeles Times)

Rust Belt Chic: Declining Midwest Cities Make a Comeback (Salon)

Ohioans Have Some of Highest Student Debt in Nation (Columbus Dispatch)

Businesses are Following the Crowd to the Cleveland Asian Festival (Plain Dealer)

Coleman Wants NBA Team For Columbus (Columbus Dispatch)

Procter & Gamble to Move Beauty Unit to Singapore From Cincinnati (Reuters)

Residents in Cleveland’s Detroit-Shoreway Neighborhood Stop Criminal Activity (NewsNet 5)

Cleveland’s Ingenuityfest to Move This Year to Warehouses and Lakefront (Plain Dealer)

Ohio House Passes Election Law Repeal (WKSU News)

Coventry Street Arts Fairs Canceled For Summer in Cleveland Heights (Plain Dealer)

The Curse of Chief Wahoo (Cleveland Scene)

Experts: Northeast Ohio Litter Problem Growing, More Education Needed (NewsNet 5)

Positively Cleveland Aims to Shape Region’s Image (Crain’s Cleveland Business)

Riding the Fracking Boom (Columbus Dispatch)

Ohio Revenue Beats Projection by $350M. Legislators Seek to Spend Surplus. (Toledo Blade)

Cleveland’s Dynamic Decade, 1912-22, Can Teach Us a Lot Today: Brent Larkin (Plain Dealer)

Cleveland’s Downtown Rebound – Richard Florida (TheAtlanticCities.com)

Ohio Bill Could Ban Teen Drivers’ Texting (Toledo Blade)

Obama vs. Romney: Ohio is Now Too Close to Call (Plain Dealer)

Northeast Ohio Counties Fail to Meet Ozone Standards (Akron Beacon Journal)

Employers Save $422 Billion If They Dump Health Coverage. Will They? (Washington Post)

Northeast Ohio Wine Growers “Devastated” by Hard Freeze (Newsnet5)

Ferry Break Down Leaves Pelee Island Isolated (Fremont News-Messenger)

FirstEnergy Will Keep Some of Its Older Plants Open Until 2015 and Launch Nearly $1 Billion in Transmission Upgrades (Plain Dealer)

Deteriorating Levee Threatens Historic Zoar (Akron Beacon Journal)

Cleveland Shares Spotlight in HBO Film on Obesity (Plain Dealer)

Pennsylvania Boom Shows Ohio What Might Be Ahead (Akron Beacon Journal)

Cash Chase Intensifies at Ohio’s Statehouse – Tom Suddes (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Lags Neighbors on Tourism Marketing (Columbus Dispatch)

Cleveland is Growing Faster Than its Suburbs as Young Professionals Flock Downtown (Plain Dealer)

First Unitarian Church Installs High-Tech Solar Array (Plain Dealer)

Cleveland Student Wins Maltz Essay Contest Grand Prize (Cleveland Jewish News)

Cleveland State University Finding New Ways to Attract First-Year Students (Plain Dealer)

Lung Association Report Shows Some Air Quality Improvement in NE Ohio (News-Herald)

Top Northeast Ohio Manufacturers Post Big Earnings Gains as Industrial Economy Improves (Plain Dealer)

Ohio Steel Mills Expand to Meet Demand in Energy and Auto Industries (New York Times)

Click Here For More News Aggregator Archives

Myth, Modernity, and Mass Housing: The Development of Public Housing in Depression-Era Cleveland by Jennifer Donnelly

Myth, Modernity, and Mass Housing: The Development of Public Housing in Depression-Era Cleveland by Jennifer Donnelly

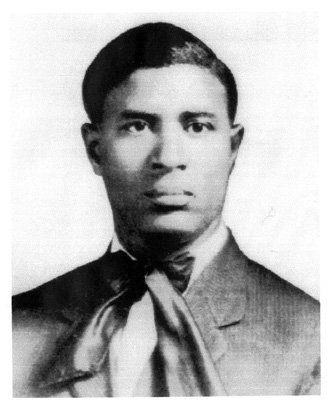

Inventor Garrett Morgan, Cleveland’s Fierce Bootstrapper by Margaret Bernstein

Ohio Historical Society Photo

INVENTOR GARRETT MORGAN,

CLEVELAND’S FIERCE BOOTSTRAPPER

By Margaret Bernstein

Garrett Morgan was a boundary-pusher and a status-quo smasher.

The son of Kentucky slaves, he moved to Cleveland in 1895, where he would become one of Ohio’s most prolific inventors. His curious mind seemed to crank at breakneck speed at all times, ferreting out problems that needed to be solved and providing the creative spark for his many inventions.

But neither Cleveland nor the nation were ready for a black man operating on such an entrepreneurial level in the early 1900s.

Just like he invented many “firsts,” Morgan himself was a first in many ways as he tried to insert himself and his inventions into the economic mainstream. And as a result, he collided repeatedly with social mores that for centuries had kept blacks in their place.

Persevering in the face of barriers and professional slights, he learned to navigate his way within the tightly segregated confines of 20th century America, although it sometimes meant he had to disguise his race in order to sell his products.

Morgan designed many items, including two life-saving devices – a gas mask that helped firefighters and soldiers survive in suffocating circumstances, and a traffic signal that restored order to intersections that had become chaotic and dangerous after the advent of the automobile.

He even invented institutions that helped nurture Cleveland’s fledgling black middle class. Once Morgan’s products earned him enough income to support his family, he started up a black newspaper, a black businessman’s league and even a black country club.

Decades after his death, it’s not unusual for this black Clevelander to be mentioned prominently during Black History Month, always a time when the achievements of African-Americans are listed and lauded across the nation.

Today he is recognized in his adopted hometown as well. Cleveland has a school, a waterworks plant and a neighborhood square named for the famed African-American inventor.

But these accolades arrived long after he could enjoy them. Although he eventually earned enough to live off his inventions and enjoyed a standard of living experienced by few blacks, he always felt blocked by barriers placed on him because of his race.

——————————

Garrett Augustus Morgan was born in Kentucky on March 4, 1877, the seventh of 11 children.

His parents, both of mixed parentage, had been slaves before the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

His father, Sidney Morgan, was the child of a female slave and a Confederate colonel, John Hunt Morgan. But Sidney Morgan’s father was also his family’s slave owner, and as a result the child suffered great physical abuse from his owners. History books show that this was a common plight for mulatto slaves – their owners would treat them cruelly since they were the physical reminders of an indiscretion on the part of a white man.

“Morgan’s father shared stories of the cruelty and abuse he had suffered, and sought to teach his son about the racial prejudices he would surely have to face in the world,” according to a detailed biographical essay on Morgan that appeared in a 1991 issue of Renaissance magazine.

His mother, Eliza Morgan, was half-Indian and half-black, and reportedly received her maiden name from her slave master. Her father, a Baptist minister, was a spiritual and law-abiding man. His deep and abiding faith would go on to have a big influence in Garrett’s life, giving him patience when he found doors to opportunity slamming in his face.

Young Garrett Morgan attended elementary school in Kentucky and worked on his parents’ farm.

It was a brutal time in Morgan’s native Kentucky, which was still reeling with resentments caused by the abolition of slavery. Lynchings of black men happened frequently in the 1880s and 1890s. Garrett Morgan showed the ambition and independent nature that eventually would make him a wealthy man when he decided, as a teen, that he would leave his family to head north.

At age 14, he arrived in Cincinnati with just a few cents in his pocket. He got a job as a handyman for a white property owner.

Morgan had only attained a fifth grade education while growing up in Claysville, Ky. “He knew how to read. He could write and he could figure,” said his granddaughter, Sandra Morgan of Cleveland, in a 2012 interview.

“But he had higher expectations for himself,” she added. And so he used his earnings as a young teen to hire personal tutors to teach him English and grammar. These competencies, he hoped, would help him get ahead.

Yet young Garrett found that Cincinnati’s racial dynamics did not seem much different from the Jim Crow restrictions of the deep South. A few scattered lynchings had been reported in southern Ohio too, during the years Morgan lived there.

And so he decided to move on. Cleveland seemed as good a place as any to land, since Morgan had some relatives in northern Ohio. He packed up his things and arrived in the area on June 17, 1895. He was one of the earlier blacks to migrate to the area. In 1890, just over 3,000 blacks had been recorded in Cuyahoga County.

Taking a room in a Central Avenue boarding house, Morgan began looking for work. According to Renaissance magazine, his enthusiasm was doused quickly, as he was told over and over, “We don’t employ niggers here.”

He eventually landed a job sweeping floors at Roots & McBride, a sewing machine factory, earning $5 a week. The youth proved to be a quick study, and he had a strong work ethic. He taught himself to sew and to repair sewing machines, and soon started working as a repairman.

Roots & McBride became the setting where his inventor’s spirit took root, and Morgan soon created his first invention — a belt fastener for sewing machines. He sold the idea in 1901 for $150.

In 1907, the Prince-Wolf Company hired him to be their first black machinist. There he met an immigrant seamstress from Bavaria, Mary Hasek. “They would engage in innocent conversations, until Morgan was warned by his supervisor that black men were not allowed to talk to white women in the company. Incensed at being told who he could and could not speak to because of his color, Morgan went to the Personnel Office and quit,” according to Renaissance magazine.

Morgan had been saving his money for years, with a goal of being his own boss. This was the moment, he realized. Using his savings, he rented a building on West Sixth Street and opened a sewing machine repair shop. It was just a few blocks from the Prince-Wolf Co.

These were tough times for African-Americans, but Morgan vowed to make his business a success. He was known to have a motto: “If a man puts something to block your way, the first time you go around it, the second time you go over it, and the third time you go through it.”

While building his business, he also worked hard at another goal: pursuing the seamstress who had caught his eye, Mary Hasek. Although her family refused to accept the interracial relationship, Mary had an independent streak herself and she fell in love with her outgoing and ambitious suitor. The couple married in 1908.

His business had been profitable enough to allow him to build a home at 5204 Harlem Ave. in Cleveland, where he later brought his mother to live, after his father died.

With Mary at his side, Morgan expanded his enterprises. The couple began manufacturing clothing, and developed a line of children’s garments.

Granddaughter Sandra Morgan remembers fondly the beautiful velvet coats with matching muffs that she wore as a little girl, all handmade by Mary. “My party coats, my summer clothes – my grandmother made everything.”

Garrett and Mary’s marriage lasted more than 50 years, until their deaths in the 1960s. Mary came from a big family, but she had little contact with her relatives after she married a black man. She was even excommunicated from her Catholic faith. Sandra Morgan, who still keeps Mary’s rosary and her Bible written in German, believes it hurt her grandmother deeply.

Garrett Morgan didn’t have much contact with his family either after leaving his native Kentucky. For him and his wife, their three children became their world, and they tried to keep their clan closely knit. “I can still remember going to my grandmother’s house, it was sacred. Every Sunday, you were at that house for dinner,” Sandra Morgan said.

And although she was just a young child in 1963 when her grandfather died, she remembers well the values he instilled. “When my grandfather came to Cleveland, he really did work with his hands and worked hard to pull himself up by his bootstraps.”

Her father, Garrett Jr., who pitched in to help his father sell his products, had a similar work ethic and passed that credo down to her: “There’s no slackers in the Morgan family” was a succinct motto they lived by.

At his home near East 55th Street and Superior Avenue, Garrett Morgan Sr. spent hours tinkering in his workshop, trying to come up with solutions to common problems. Around 1910, he had been working on a way to ease the scorching caused by a sewing machine’s rapid movement against wool, when he stumbled into a valuable discovery.

It happened by accident, when Morgan wiped his hands on a cloth after experimenting with a lye-based solution in his workshop.

Later, he noticed the woolen fibers had gone from crinkly to straight. Curious to see if he could replicate the result, Morgan experimented on a neighbor’s Airedale dog, and eureka: G.A. Morgan’s Hair Refining Cream was born.

It was the first product ever shown to chemically straighten kinky black hair – a forerunner to the popular hair relaxers of today — and Morgan shrewdly deduced its potential marketability. To go along with it, he developed a comprehensive line of hair care products, from his Hair-Lay-Fine Pomade that “makes unruly hair lay where you want it” to a special pressing comb for “heavy hair.” Morgan called his hair products “the only complete line of hair preparations in the world,” and soon he had a thriving business shipping the items to drugstores across the country.

He did whatever he thought it took to market his hair products. At one point, Morgan purchased a calliope and positioned the steam-powered organ inside a bus. He and son Garrett Jr. would blast the calliope loudly as they drove through Cleveland neighborhoods, attracting attention from people on the street whom they would then direct to drugstores that sold their creams and other items.

Around the same time, he was also working on “safety helmet” that he first developed in 1912. His intent, Morgan once wrote, was to invent an apparatus that could “provide a portable attachment which will enable a fireman to enter a house filled with thick suffocating gasses and smoke and to breathe freely for some time therein, and thereby enable him to perform his duties of saving lives and valuables without danger to himself.”

Morgan had long been aware of the fire hazard posed by wooden shanty houses like the ones in some areas of Cleveland and also in his rural Kentucky hometown. A fire could race through these homes in an instant, giving occupants barely seconds to get out. Morgan sometimes joked that that these homes went up in flames so quickly that the first thing to burn would be the fire bucket. But he was serious about the need to devise a solution.

In 1914, he patented his version of the gas mask. His safety hood had two tubes that extended to the floor, where Morgan assumed that fresh air was most likely to be found in case of fire. His device included a backpack of unpressurized reserve air.

Always quick to seek ways to sell his products after obtaining patents, Morgan traveled the nation after 1914 to demonstrate his device to fire departments. Knowing fire departments in the South would have no interest in enriching a black inventor, Morgan hired a white actor to pose as the inventor while Morgan dressed up as an Indian chief in New Orleans during a demo at the International Association of Fire Chiefs. During their schtick, the actor would announce that “Big Chief Mason” would don the mask and go inside a smoke-filled tent for 10 minutes. The audience was stunned when Morgan emerged unharmed after 15 minutes in the suffocating tent, and orders began to flow.

He had disguised his identity previously in 1911, when his mask won an award at the New York Safety Exposition. Again, he sent a white actor to accept the honor. “It was a little bittersweet that he couldn’t accept his own award,” said his granddaughter. “He couldn’t claim credit for his own work.”

Yet Morgan’s strategy paid off, literally. Mine owners and fire departments from across the United States and Europe began purchasing the hoods, and the U.S. Army used a slightly redesigned version of the Morgan mask during World War I.

The mask would endure a huge test in Morgan’s adopted hometown of Cleveland, when a group of miners was injured in a shaft under Lake Erie on July 25, 1916. An explosion had torn through an underwater tunnel, trapping more than a dozen men in an area filled with smoke and gas.

Morgan’s phone rang at 3 a.m. in the morning, summoning him to the scene. Still in his night clothes, he rushed to the lake with his safety hoods, bringing along his brother Frank and a neighbor.

Although rescue accounts differ, it is believed that his rescue team brought six men back to the surface and saved their lives, proving the hood’s effectiveness.

But the inventor’s heroism resulted in more slights. The Carnegie Hero Commission declined to recognize the Morgan rescue as an act of bravery. Even Morgan’s request for the city of Cleveland to help him with his medical bills, after he encountered noxious smoke in the waterworks tunnels, was unsuccessful.

Morgan’s granddaughter said her family also believes that sales of the gas mask began to drop as news traveled the nation that the inventor was a black man. “As far as I know, they were selling very well until it was discovered that the patent holder was black, and then sales dried up. That was very upsetting for him.”

Morgan, who had moved to Cleveland in search of opportunities denied to black men in the South, was clearly disappointed, Sandra Morgan said. He wanted nothing more than to be known as a “black Edison,” he told his family.

What he craved wasn’t the fame enjoyed by Thomas Edison, known nationally as “the Wizard of Menlo Park.”

Morgan wanted to live without limits, to be fairly remunerated for his many innovations and create a business empire as Edison had done. It disturbed him that he wasn’t afforded that chance. Of course, few inventors reached the heights achieved by Edison – it wasn’t just race that kept Morgan from following in his footsteps.

But opening doors closed to blacks had been a priority for Morgan throughout his life. A fervent bootstrapper, he believed strongly in doing all he could to strengthen Cleveland’s black community. In 1920, Morgan started a newspaper, the Cleveland Call, the predecessor to Cleveland’s Call & Post. Even this decision was a stab at righting a wrong against blacks. At the time, blacks weren’t allowed to advertise in white papers, and also reporting about blacks was considered negative and stereotypical.

By that time, Morgan had become a wealthy business owner with dozens of employees.

Automobiles were just becoming popular with the masses, and Morgan is believed to be one of the first black men in Cleveland to own one. From then on, “He always loved sweet-looking rides,” his granddaughter recalled with a laugh.

At the time, cars and horse-drawn buggies were all competing with pedestrians for space on Cleveland’s crowded streets. Morgan realized a device to control the haphazard traffic was needed, and devoted himself to inventing a solution.

On Nov. 20, 1923, he received a patent for the invention for which he’s best known: the traffic signal.

Although many say Morgan invented the traffic light, that is not technically true. There were no lights on Morgan’s device.

Morgan’s manually operated signal was mounted on a T-shaped pole. It gave people approaching an intersection three choices: stop, go or stop in all directions (which halted cars and buggies so that pedestrians could move safely).

General Electric, realizing the necessity for Morgan’s invention, purchased the patent from him for $40,000.

In 1923, he used some proceeds from sale to purchase a large piece of property near Wakeman, Ohio. There he created Ohio’s first black country club – a place where middle-class blacks could enjoy recreation like horseback riding, fishing and horseshoes. “The all-black facility, however, was not wanted in the area by local whites,” reported Renaissance magazine, which said that Klan members rode onto the property one night and burned a cross.

“Morgan and his brothers ran the m off with guns and warnings of their own. The KKK never returned, and the club enjoyed uninterrupted success until Morgan lost the bulk of his money in the 1929 stock market crash. With a freeze on his savings account, Morgan wisely sold 200 acres of the Wakeman land to pay the taxes on the remaining 200.”

Morgan died in 1963. The city of Cleveland never did grant his request for pension benefits in light of injuries sustained in the 1916 rescue.

Sandra Morgan said her family still has a letter that Morgan sent to Cleveland mayor Harry Davis expressing anger that he wasn’t compensated after the waterworks disaster. “I’m not an educated man, but I have a Ph.D from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment,” it began.

Did he die a bitter man? Sandra Morgan thinks not. Her grandfather had expressed disappointment many times over, but just as he tirelessly tested his inventions, Garrett Morgan took pride in surviving test after test of his mettle. The sale of the traffic signal had put him in a position where he didn’t have to work for anyone else any more, leaving him free to pursue the things that interested him most. And with that freedom came a sense of peace, she believes.

His headstone at Lakeview Cemetery reads simply: “By his deeds, he shall be remembered.”

And in 1991, 28 years after his death, one of his most heroic deeds — saving lives that seemed doomed in the underwater tunnel beneath Lake Erie — was remembered and recognized. The city of Cleveland finally honored Morgan by renaming its lakefront waterworks plant for him.

For more on Garrett Morgan, click here

War of 1812: Culmination of 20 Years of Conflict Opened Up the Future for Ohio: Elizabeth Sullivan

Courtesy of the Plain Dealer June 10, 2012

War of 1812: Culmination of 20 years of conflict opened up the future for Ohio: Elizabeth Sullivan

When federal census-takers ventured into the wild Ohio country in 1800, they found (pdf) 45,365 settlers already living in “the Northwest Territory.”

So many had flooded into this frontier land — from the East Coast, looking for cheap, fertile land; from slave-owning states, wanting to live in a slave-free area; from eastern cities, looking to profit on land speculations — that Ohio had almost reached the magic 60,000 number needed to become a state. It achieved that milestone in 1803.

These newcomers had headed for Ohio despite a series of shockingly violent wars and raids in the 1790s pitting early settlers against indigenous Indian tribes determined to hold on to land specifically guaranteed them in a 1768 British treaty.

An equal thirst for territory propelled the migrants, however — the same inexorable expansionism that set the stage for Ohio’s part in the War of 1812, which started 200 years ago this month.

The war, as it was fought in Ohio, was in many ways the logical extension of more than a decade of Indian warfare for title to this verdant tract of land. Even before war was formally declared on June 18, 1812, the enterprise was viewed with far more enthusiasm on the Ohio frontier than in Philadelphia, New York or Washington.

While East Coasters fretted about the serious economic repercussions, Ohioans correctly understood the stakes as nothing less than control of America’s frontier, the key to the American experiment.

For more than a decade, folks in Ohio and neighboring Kentucky had been on the front lines of a series of Indian wars fought with the help of British weapons and other provisions.

Long after the Revolutionary War had ended, it seemed to many local settlers that Britain was determined to kill the United States through its back door, using indigenous tribes as proxies.

While that impression was exaggerated — the British were much more interested in preserving their stake in the lucrative fur trade than in starting another expensive war — British officials delayed enlightening Indian allies about their narrow aims, or about the 1783 treaty ending the Revolutionary War, when Britain had ceded to the fledgling United States the entire “Old Northwest” that the tribes considered theirs.

The ceded land included all or parts of what was to become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota — although Britain kept armed forts in the area, ostensibly to secure its fur-trading interests.

In this way, more than a quarter-million square miles of prairie, deciduous forests, rivers, swamplands and fertile land became the logical pathway for U.S. expansion — America’s “manifest destiny” long before the phrase was coined.

That’s also why the 1790s Indian wars naturally morphed into the War of 1812 — which did settle, once and for all, America’s expansionist destiny westward, although not northward into Canada, after several invasion attempts failed.

No mere skirmishes, the 1790s wars involved pitched battles by a federation of Indian warriors who knew the stakes, acting in concert under skilled military leadership — and exacting, in 1791, what’s still the worst single-battle U.S. Army loss against Native Americans.

On Nov. 4, 1791, on the Wabash River near present-day Fort Recovery in western Ohio, more than 600 U.S. Army officers, men and militia members under the command of Arthur St. Clair, an aging Revolutionary War veteran afflicted with gout, were slain, along with hundreds of their camp followers, during a surprise attack by 1,000 warriors led by Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket.

That was more than twice the casualties of the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The sweeping 1795 Treaty of Greenville was supposed to put the Indian claims in Ohio to rest.

That treaty followed the trouncing that troops led by U.S. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne dealt to a united force that included Shawnee, Wyandot, Delaware and Miami tribesmen at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, in present-day Maumee.

But the 1790s wars did not resolve all of the competing claims.

When Ohio Gov. Return J. Meigs Jr. called in April 1812 for troops to assemble in Dayton — months before war was formally declared — so many showed up to fight that the Army didn’t have supplies for all of them.

Qualified commanders also were in short supply. Local militias near Dayton had to take up armslater that summer to defend the area’s settlements, after the ignominious capitulation in August 1812 of William Hull, another ailing Revolutionary War veteran, who had shockingly surrendered his Ohio and U.S. troops at Detroit to a smaller British-American Indian force, virtually without firing a shot.

Fortunately, other U.S. forces had more success. And the magnificent victory, in September 1813, of Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry in the naval Battle of Lake Erie was a strategic triumph that cut key British supply lines, although it would take another year to end the war.

By 1820, more than half a million people were in Ohio, many hoping to make their fortunes, others heading elsewhere. I was amazed to see, when I looked closely at the census earlier this year, that no fewer than 10 of my direct forebears were in Ohio by 1820.

They came because of hatred of slavery (James Sullivan from North Carolina between 1808 and 1811), thirst for cheaper land (Thomas Crook from Maryland in 1814), the adventure of the frontier (Jacob Kessler and Henry Horn, in-laws and Revolutionary War veterans, from Pennsylvania via Virginia between 1806 and 1814) and to make money in the state’s nascent manufacturing that needed abundant water for power (George Seager, who in about 1811 had emigrated illegally from Britain, where his skills as a wool carder and machine maker were considered an industrial secret “not for export”)

Thomas Crook, my great-great-great-grandfather, briefly served in the 1812 war at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, according to his sworn affidavit, then moved to Wayne Township northeast of Dayton — named for the general who’d defeated Native American forces in 1794. Many of Wayne Township’s early residents were veterans of the Revolutionary, Indian or 1812 wars.

One of Crook’s younger sons was George Crook, a West Point graduate and later famed Indian fighter who became an early champion of Native American civil rights.

Gen. Crook’s attempt in the late 1800s to seek redress for the broken promises to Apache leaders and others whom he’d first fought and then befriended was a lonely battle that alienated him from some of his oldest military friends.

But it suggests how combat veterans often see war — as a failure to act decisively to redirect the elements that are spinning out of control and propelling conflict and violence.

Gen. Crook, who was born on the Ohio frontier a dozen years after the War of 1812 ended, would have grown up surrounded by men who understood that.

Sullivan is The Plain Dealer’s editorial page editor.

Remembering Cleveland’s Muhammad Ali Summit, 45 Years Later-Plain Dealer 5/3/12

Remembering Cleveland’s Muhammad Ali Summit, 45 Years Later-Plain Dealer 5/3/12

Courtesy of the Plain Dealer

Remembering Cleveland’s Muhammad Ali Summit, 45 years later

Published: Sunday, June 03, 2012

On June 4, 1967 at 105-15 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, a collection of some of the top black athletes in the country met with — and eventually held a news conference in support of — world heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali (front row, second from left), about Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the U.S. Army in 1967. • Mouse over the picture to put names with the famous faces and read details.

CLEVELAND, Ohio — On a sunny Sunday afternoon in early June 1967, several hundred Clevelanders crowded outside the offices of the Negro Industrial Economic union in lower University Circle. None of those gathered, including a collection of the top black athletes of that time, realized the significance of what would happen in that building on this day.

Muhammad Ali, the most polarizing figure in the country, was inside being grilled by the likes of Bill Russell, Jim Brown and Lew Alcindor, who would later change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. They weren’t interested in whether Ali was going to take his talents to South Beach or any other sports labor issues.

They wanted to know just how strong Ali stood behind his convictions as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. The questions flew fast and furious. Ali’s answers would determine whether Brown and the other athletes would throw their support behind the heavyweight champion, who would have his title stripped from him later in the month for his refusal to enter the military.

“When I look at the situation in Florida (Trayvon Martin case) and when I look through all my adult life, there’s always been a period where something happens that causes this country to struggle, be it racial or whatever,” said former Green Bay standout Willie Davis. “I look back and see that Ali Summit as one of those events. I’m very proud that I participated.”On June 4, 1967 at 105-15 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, a watershed moment occurred in the annals of both the Civil Rights Movement and the protest against the Vietnam War. Every cultural force convulsing the nation came together – race, religion, politics, young vs. old, peace vs. war. This is the story about how such an extraordinary meeting developed. How it transpired in Cleveland. And of what that meeting means now, looking back though the lens of 45 years.

The core of the summit was the NIEU, later named the Black Economic Union (BEU).

The organization was co-developed by Brown in 1966, a year after he retired from the NFL to become a full-time actor. The BEU served various communities across the country, mostly in economic development. The BEU also supported education and other social issues within the black community.

The BEU and this meeting with Ali stemmed from Brown’s social consciousness. For the meeting with Ali, Brown brought together other socially conscious black athletes of the time. Besides Russell, Alcindor and Davis, there was Bobby Mitchell (Washington Redskins), Sid Williams (Browns), Jim Shorter (Redskins), Walter Beach (Browns), John Wooten (Browns), Curtis McClinton (Kansas City Chiefs) and attorney Carl Stokes.

“The principal for this meeting of course was Ali,” McClinton said. “The principal of leadership for us was Jim Brown. Jim’s championship leadership filtered to all of us.”

The Sixties

The United States in the 1960s was ripe for political, social and cultural change. It was a time of upheaval, and re-awakening.

“The time dictated the passion in all of us,” Brown said.

Forty-five years ago, the United States was in the midst of a Civil Rights movement. There was also an increase in protests against the Vietnam War. Malcolm X was killed in New York in 1965. Later that year, black football players refused to play in the AFL All-Star Game in New Orleans because of racism and discrimination in that city. The game was moved to Houston. In July 1966, riots erupted in the Hough neighborhood of Cleveland. Two major race riots erupted in Newark and Detroit during the summer of 1967. Opposition to the Vietnam War grew with protests on college campuses and in several major cities. And 10 months after the Ali Summit, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis.

In many ways, Cleveland was also the epicenter of black political and social progress. In November of ’67, Stokes became the first black mayor of a major U.S. city when he was elected in Cleveland. The city became a destination for thousands of blacks who migrated from the south because of job opportunities. When it came to sports, the Browns were popular in the black community, mostly because of their history with black players, such as Marion Motley, Bill Willis and Brown.

“Black people were coming to Cleveland from all over the country to see what we were doing here politically and economically, because no other city was doing it like we were,” said former BEU treasurer Arnold Pinkney, a long-time entrepreneur and political activist.

“Cleveland was a hotbed for black power, energy and Black Nationalism at this time,” said Leonard N. Moore, University of Texas professor and author of the book, “Carl B. Stokes and the Rise of Black Political Power.”

“In so many ways, it was fitting that the meeting happened on the East Side of Cleveland,” he said.

A little over a month before the Cleveland gathering, Ali refused to step forward for induction into the U.S. Army in Houston. That set off a firestorm of criticism of the champ. Ali was also a member of the Nation of Islam, broadly seen as an anti-white cult, even in some circles within the black community.

Harry Edwards, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of California-Berkeley, said there was so much consternation concerning the war and Ali that the fighter became symbolic of almost every rift in society.

“He was already regarded as a loud-mouth Negro while he was Cassius Clay,” said Edwards, referring to Ali’s birth name before his conversion to Islam. “When he joined the Nation of Islam, that exacerbated it even more.”

Ali’s stance helped ignite the rising level of anti-war sentiment.

“The anti-war movement really hit the headlines when Ali refused induction and made his statement about not having any quarrel with the Viet Cong,” Edwards said. “And then to refuse to comply with the draft, that lined up all of those people who were on one side or the other of the Vietnam War.”

Enter Jim Brown

In 1967, Brown was in his second year of retirement after leaving the sport as the NFL’s all-time leading rusher. His post-NFL career was spent as an actor, but Brown never lost his zeal as a social activist. When Brown helped form the BEU, the organization established offices in Los Angeles, Kansas City, Philadelphia, New York, Washington and Cleveland. His former teammate, John Wooten, became the executive director of the Cleveland office. Everyone in the meeting with Ali, with the exception of Russell, was a BEU member.

Ohio State graduate student Robert Bennett III, who will complete his dissertation thesis on the BEU later this year, said supporting Ali was not out of the ordinary for the BEU.

“Oftentimes when you look at the history of black athletes, it often looks at their achievements on the field,” Bennett said. “And it’s rare for someone to look at their social or political activism off the field. The athletes involved with the BEU were about defending and supporting issues that supported the black community.”

Shortly after Ali’s refusal to join the military on grounds of being a conscientious objector, Brown received a telephone call from Ali’s manager, Herbert Muhammad. Several boxing governing bodies had already suspended or threatened to suspend Ali’s boxing license. Brown said Herbert wanted him to help convince Ali to reconsider because of the potential loss of income, and because of the anticipated backlash.

Herbert Muhammad was torn because of his religious faith, but he was also in the business of helping Ali make money.

“Herbert wanting Ali to go into the service was a shocker,” Brown said. “I thought the Nation of Islam would never look at it that way. But Herbert figured the Army would give Ali special consideration so he would be able to continue his career. But he couldn’t talk to Ali about that, so he reached out to me and I had the dilemma of finding a way to give Ali the opportunity to express his views without any influence. I never told Ali about my conversation with Herbert. I never told anyone, really.”

There was another backdrop to the meeting. Bob Arum and Brown were partners in Main Bout, Arum’s company that promoted Ali’s fights. Convincing Ali to go into the military would provide economic opportunities for the athletes in the summit.

“The idea was that these guys would become the chief closed-circuit exhibitors for Ali’s fights all over the United States,” Arum said. “Each of them would get a particular region and they would make a nice chunk of change every time Ali fought.”

Subsequently, Brown reached out to Wooten and asked him to contact some of the top black athletes in the country to attend a meeting in Cleveland with Ali.

“Herbert wanted me to talk with Ali, but I felt with Ali taking the position he was taking, and with him losing the crown, and with the government coming at him with everything they had, that we as a body of prominent athletes could get the truth and stand behind Ali and give him the necessary support,” Brown said.

Where and when

The athletes’ response did not surprise Wooten.

“After I called all of the guys and explained what we were meeting about, they didn’t ask who’s going to pay for this or that, they just asked where and what time,” Wooten said.

Alcindor, who had just finished his sophomore year at UCLA, didn’t hesitate to make the trip.

“Muhammad Ali was one of my heroes,” said Abdul-Jabbar, who was active in the BEU office in Los Angeles. “He was in trouble and he was someone I wanted to help because he made me feel good about being an African-American. I had the opportunity to see him do his thing [as an athlete and someone with a social conscience], and when he needed help, it just felt right to lend some support.”

More importantly, the meeting wasn’t just for Ali.

“Our assembling there was about Ali defining himself, because that definition was a part of us,” McClinton said.

The athletes at the summit were not going to give Ali blind support. Many needed answers to exactly why Ali claimed to be a conscientious objector. There was some confusion regarding Ali’s motives. Three years earlier, Ali failed the Armed Forces qualifying test due to sub-par writing and spelling skills. In early 1966, the tests were revised and Ali was reclassified as 1A, making him eligible for the draft. Initially, Ali said he didn’t understand the change and there was no reference to religion or being a conscientious objector. Many wondered if he was only upset because of the interruption to his boxing career.

At the summit, Ali also had to convince a group that had several members with a military background. Brown, as a member of the Army ROTC, graduated from Syracuse as a second lieutenant. Wooten completed his military obligation in 1960. Shorter served in a reserve unit, and Mitchell served with a military hospital unit in 1962. Beach spent four years in the Air Force. Stokes served in World War II, and McClinton served in the Army Signal Corps.

Making his case

Brown didn’t set up a gauntlet for Ali. He also did not set up a meeting for Ali to waltz through.

“I wanted the meeting to be as intense and honest as it should’ve been, and it was because the people in that room had thoughts and opinions, and they came to Cleveland with that purpose in mind,” Brown said.

“We weren’t easy on him,” Mitchell said. “We weren’t slapping hands. In that room, especially early on, it got a little heated.”

How heated?

“F. Lee Bailey [a famous trial lawyer] would’ve been proud in the way we questioned the champ,” Wooten said. “Those guys shot questions at the champ, and he took them, and fought back. It was intense because we were all getting ready to face the United States public relations machine — the media, and put our lives and careers on the line. What if this fails? What if he goes to jail?”

Although it wasn’t discussed as a group before the meeting, many of the men planned to convince Ali to accept his call to the military.

“But after about 15 minutes of being there, I’m saying to myself, ‘No way is this guy going to change his mind,'” Davis said.

Ali made it clear that he would not participate in the Vietnam War. He spoke on Islam, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, and black pride, but it all came down to his religious beliefs, and nothing was going to convince him otherwise.

“Jim told me that Ali talked for two straight hours,” Arum said. “And you have to understand that at that time, Ali was functionally illiterate. And here he was in a room with these great athletes who were all college educated, but he was able to convince all of them that the path he was taking was the correct one. And people at that point and time didn’t realize how smart Ali was.”

In fact, Ali was so convincing that many in the room nodded their heads in agreement whenever Ali made several points.

“The champ stood strong,” Wooten said.

“During those hours, he said he was sincere and his religion was important to him,” Mitchell said. “He convinced all of us, even someone like me, who was suspicious. We weren’t easy on him. We wanted Ali to understand what he was getting himself into. He convinced us that he was.”

McClinton also noted how the summit was not entirely about supporting Ali as a conscientious objector.

“Our presence there was more to the freedom for Ali to go left or right,” McClinton said.

“We didn’t have a right to tell Ali what to do,” Williams said. “All we could do is show our support for him in whatever he was going to do. That decision was up to him and he made it.”

Following the meeting, Brown led the group to a press conference. Russell, Ali, Brown and Alcindor (Abdul-Jabbar) sat in the front row at a long table. Stokes, Beach, Williams, McClinton, Davis, Shorter, and Wooten stood behind them.

Brown said the group supported Ali and his rights as a conscientious objector. And they felt his sincerity.

‘Absolute and sincere faith’

Russell declined to comment when approached for this story during the NBA All-Star Weekend in February, but shortly after the summit, Russell said this to Sports Illustrated in the June 19, 1967 issue:

“I envy Muhammad Ali. … He has something I have never been able to attain and something very few people possess. He has absolute and sincere faith. I’m not worried about Muhammad Ali. He is better equipped than anyone I know to withstand the trials in store for him. What I’m worried about is the rest of us.”

Supporting Ali certainly wasn’t a popular move, but Brown and the others were willing to take the risk. None of the participants could cite any direct fallout when it came to supporting Ali, but being there for a friend was worth any risk.

“We didn’t care about any perceived threats,” Wooten said. “We weren’t concerned because we weren’t going to waver. We were unified. We all had a real relationship with each other and we knew we were doing something for the betterment of all.”

In an even broader sense, the Ali Summit — not known by that name at the time — helped to validate Ali’s religious beliefs. But those beliefs and the summit could not prevent the actions of the U.S. Government two weeks later when Ali was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years. He stayed out of prison as his case was appealed. The Supreme Court would overturn the decision in 1971.

But the summit had other immeasurable benefits.

“We knew who we were,” said McClinton of the athletes who stood united 45 years ago. “We knew what we had woven into our country, and we stood at the highest level of citizenship as men. You name the value, we took the brush and painted it. You raised the bar, we reached it. You defined excellence, we supersede it. As a matter of fact, we defined it.”

© 2012 cleveland.com. All rights reserved.