Water As An Economic Tool (PDF)

By Brent Larkin

Northeast Ohio should regard building a vibrant water-based economy as a priority so important that the future of the entire region depends on it. It probably does.

Water isn’t the only key to a prosperous future. World-class medical facilities, biosciences, renewable and alternative energy all show promise of contributing to our 21st- century economy. But the unquestioned key to that future is an asset whose origin dates back more than a billion years—the world’s most abundant supply of fresh water.

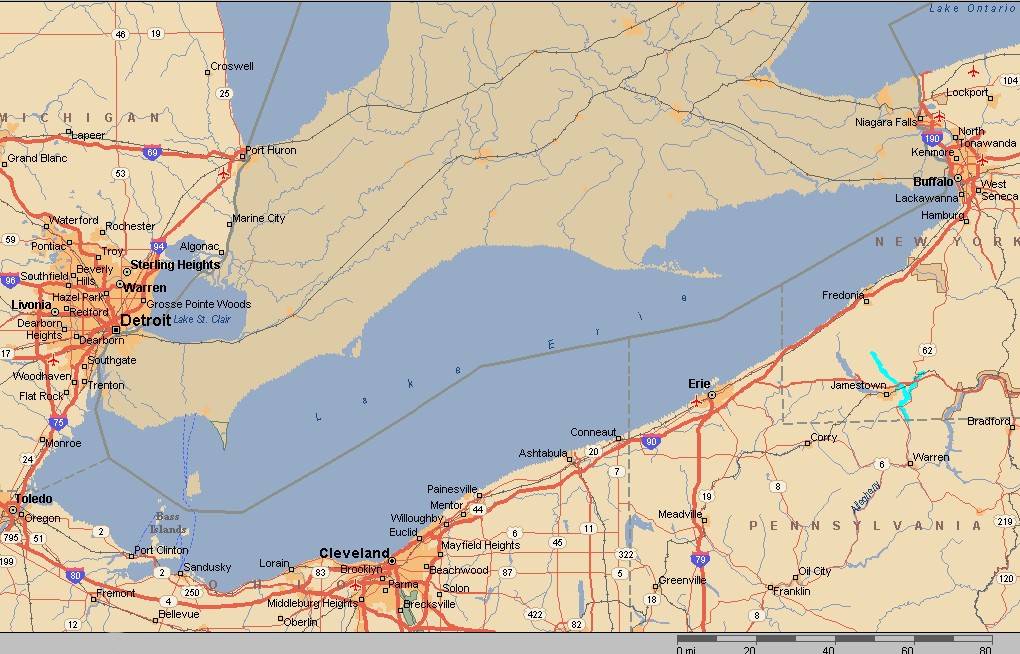

Of all the world’s water, 97 percent of it is salty. Another 2 percent is locked in ice or snow. Of that remaining 1 percent that is fresh water, the Great Lakes contain just under 20 percent of it. Lakes Erie, Ontario, Michigan, Huron, and Superior boast a total of 11,000 miles of shoreline. Recreation alone on the lakes is a $6 billion-a-year industry.

In considering the magnitude of the importance of Northeast Ohio’s most precious asset, consider that 46 percent of the world’s population does not have water piped into their home, that in undeveloped countries people must walk an average of 3.7 miles to get fresh water.

We have 6 quadrillion gallons (that’s 15 zeros) of it at our doorstep.

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.

Cleveland’s past greatness was rooted in its relationship and reliance upon that water. Lake Erie and the large albeit crooked river that flows into it (the Cuyahoga) made the city a giant in manufacturing, shipbuilding and rail transportation.

Manufacturing will remain a significant part of Northeast Ohio’s economy for the foreseeable future, but it’s decline as the centerpiece of that economy has been inexorable and—when viewed with the benefit of hindsight—inevitable.

But booming economies in the West, Southwest and Southeast are now running out of the water they so desperately need to sustain their growth. Indeed, some aquifers in California are down to 25 percent of

capacity.

So as other parts of the country—and world—dry up, cities with great quantities of clean, fresh water have the potential to enjoy an economic resurgence. By 2025, an estimated one-third of the world’s population will not have access to fresh water. As a 2008 Goldman Sachs report concluded, fresh water has become “the natural resource with no substitute.” but as Northeast Ohio plans a water-based economy, that planning requires an understanding and appreciation of history. So before explaining how water can return the region to prosperity, let’s examine its paramount role in the greatness of our past.

In 1772 and again in 1786, a missionary and geographer named John Heckewelder visited the Indian-occupied territory along the Lake Erie shoreline at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. Heckewelder was captivated by the location, which featured the vast lake and countless streams feeding into the river. It was, he thought, the ideal place for a settlement as the young nation expanded west.

On his second visit, Heckewelder established a small trading post along the Cuyahoga, close to what is now known as Tinkers Creek. He also prepared a map of the region.

Relying in part on that map, in 1796 a group of eastern investors purchased from the state of Connecticut what is now the Greater Cleveland region, paying $1.2 million for about three million acres (a little more than 30 cents an acre). They named it the territory of the Western Reserve.

In May of 1796, investors in the Connecticut Land Co. designated Moses Cleaveland as their agent to visit the territory. On July 4, 1796, Cleaveland and his sailing party of about 50 men reached Conneaut. About two weeks later, the group mistakenly thought they had reached its final destination, disappointing surveyors at the small size of the river.

So unhappy was Cleaveland’s group that legend has it they named the small river the Chagrin. More likely is the Indians had already given the Chagrin its name.

Having discovered its likely error, Cleaveland’s party continued west, and on the morning of July 22, 1796, slipped into the Cuyahoga and embarked near the area of the Flats east bank, now known as Settlers Landing. On the day the Cleaveland party landed, the east bank of the Cuyahoga represented the most western point in the United States, or its territories, not controlled by Indian tribes.

Cleaveland was exhausted, but wrote that the location—with its crystal clear lake, magnificent rivers, rich forests, fertile soil, and rolling hills—exceeded investors’ expectations. Within days, Cleaveland had struck a deal with the Iroquois to plot a village east of the river, just south of Lake Erie.

Three months after arriving, Cleaveland left the city that now bears his name, absent that first “a.” He never returned.

In the late 18th century, both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were known to ponder ways of moving goods from the west (the area now known as the Midwest) to population centers in the east. Both centered on the idea of a canal that would move products east along the Ohio River, and at one point Washington was said to recommend a canal that would connect the Ohio to Lake Erie, alongside the Cuyahoga River.

Absent access to a market, farmers in and around the new village of Cleveland struggled in the town’s early years. Then, in the early 1820s, Ohio’s leaders concluded the only way to ensure economic prosperity for the entire state was to construct a canal from the Ohio river north, through Columbus, to Lake Erie.

Many thought the canal’s northern terminus should be in Warren or Sandusky. Alfred Kelley believed that terminus should be in Cleveland. And Alfred Kelley turned out to be a very persuasive man. A lawyer, county prosecutor, the youngest elected member of the legislature, and the first president (1815) of the village of Cleveland, Kelley became the state’s most outspoken and effective promoter of the Ohio & Erie Canal.

In 1821, the state legislature began deliberating issues relating to the canal’s funding, route and construction. Kelley’s relentless lobbying paid off, and in 1825 ground was broken on the northern section of the canal that would link Akron to Cleveland. On July 4, 1827, the first boat to travel the canal route from Akron arrived in the Cleveland Harbor.

By the early 1830s, construction on the canal was complete. Economic growth was now all but guaranteed. And Alfred Kelley had earned his place as one of Cleveland’s greatest citizens.

Consider the canal’s economic impact: In 1830, about three million pounds of goods traveled the canal. By 1838, that number had grown to nineteen million. Products from central Ohio’s farmlands poured into Cleveland’s port, filling the harbor with steamboats and other vessels awaiting their turns at the dock. The dramatic increase in business at the port sparked a building boom along the river and on Superior Avenue, as schools, churches, warehouses, and office space gave birth to what was becoming one of the most vibrant and successful ports on the Great Lakes.

Cleveland could offer something unique, direct access east to New York or southeast to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. No other city on the Great Lakes had water access to New York or New Orleans.

Water was pushing this new young village on a path to prosperity.

In the summer of 1860, the Cleveland Leader, one of the city’s daily newspapers, complained of the city’s plight, “We continue to make nothing and buy everything.” That was about to change. Railroads had dramatically reduced the importance of the Ohio & Erie Canal. By the start of the Civil War, five major rail lines passed through the city. At war’s end, iron from the Lake Superior region began arriving by lake carriers in record amounts.

Much was then shipped by rail to steel manufacturers in Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Youngstown. But by 1868, Cleveland itself was home to more than a dozen steel rolling mills. As the industrial revolution generated startling economic growth across the country, for a time no city grew faster than Cleveland. Water and rail made Cleveland a manufacturing giant, the country’s second largest automotive city, and the largest shipbuilding port on the Great Lakes.

Cleveland’s water-based economy was huge, diverse, and—as the 20th century arrived—seemingly recession-proof. In 1860, Cleveland was a relatively tiny town of 43,000. Seventy years later, it was home to a world-class port and a population of more than 900,000—the nation’s sixth largest. Access to water had made it a vibrant and prosperous city. but the end of that prosperity—and the city’s wise use of its water was nearing the end.

Cyrus Eaton, Cleveland’s world-renowned industrialist, once said the Depression hit his hometown harder than any city in the country.

Indeed, the loss of jobs and the post-war flight to the suburbs launched Cleveland on a path of slow, albeit relentless, economic decline.

As the city began to lose residents and jobs, Cleveland also paid a price for not tending to its greatest asset. By the 1960s, both Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River became dangerously polluted, significantly damaging the Northeast Ohio fishing industry and dealing a crippling blow to the city’s reputation.

On June 22, 1969, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga caught fire. Flames on the river reached five stories high. Wooden bridges burned. The city’s water, the primary source of its greatness, made it the butt of jokes that linger to this day.

Three things must happen with our fresh water is it is to play a pivotal role in northeast Ohio’s economic recovery. We must: 1. keep that water here. 2. keep it clean. 3. rebuild the port as an economic hub.

For decades, Lake Erie and the river suffered as phosphorous and other industrial pollutants poured into the water unchecked, killing fish and other helpful species, giving the water an untenable odor, closing beaches, and spreading contamination north to the Canadian shoreline.

In 1972, Congress finally acted, passing the Clean Water Act, which regulates the discharge of pollutants into the nation’s surface waters, including lakes, rivers, streams, wetlands, and coastal areas. The act dramatically curtailed the discharge of untreated waste water and sewage from government and industrial sources, and eventually made both Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River safer for swimming and fishing.

The results were remarkable. But eventually, problems returned. Lake Erie today again faces significant problems—largely invasive species, sediment, and the vestiges of pollution. The lake and the river are back from the dead, positioned to play a vital role in the 21st-century economy. But it is worth restating that this rebirth will be sustained only if we keep our water clean, wisely build an economy around it, and prevent other parts of the country from tapping into what is Greater Cleveland’s most precious resource.

Toward that end, in 1986 Congress passed the Water Resource Development Act designed, in part, to prevent diversion of Great Lakes water. But many legal scholars thought the act vulnerable to a legal challenge, so in the mid-1990s representatives of the eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian provinces began negotiating a basin-wide approach to decisions on water usage.

The result was the St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact—commonly called the Great Lakes Compact, a product of more than four years of negotiations by the governors, a 39-member advisory committee, and input from thousands of U.S. and Canadian citizens. Canada enacted the compact rather quickly. Approval by the eight states and the congress took more than five years.

The Ohio House twice ratified the compact, the second time by a vote of 90–3. But Ohio was one of the last states to give its final approval because the compact stalled in the Ohio Senate for more than a year. an April 27, 2008, editorial in the Cleveland Plain Dealer—one of many the newspaper wrote urging Ohio to ratify the agreement—angrily suggested the Senate’s foot-dragging “represents one of the most unforgivable public policy abuses perpetrated upon the people of Northeast Ohio in decades.” The paper accused more than several senators of concocting “some crackpot theory” that exposed “all of Ohio to economic harm.”

After allowing some face-saving for the Senate, Ohio became the sixth state to ratify the compact. In October of 2008, President George W. Bush signed it, just days after its approval by the U.S. House and less than a month after passing the U.S. Senate.

Now the law of the land, the Great Lakes Compact essentially bans diversion of large amounts of water outside the Great Lakes. In the United States, each of the eight Great Lakes states has a seat on a water resources council. Any water withdrawal exceeding five million gallons daily must be approved by a majority of the council. Similar diversion rules apply in Canada. In Ohio, only counties straddling the Great Lakes Basin are allowed to use Lake Erie water. Diversion approved prior to the compact’s ratification, like Akron’s large scale use of Lake Erie water, are allowed to continue.

The importance of preventing diversions is enormous, as public officials in arid parts of the country have been publicly talking of preying on Great Lakes water since the early days of the 21st century. In late 2007, when he was running for president, new Mexico Governor Bill Richardson called for a national policy to consider redistribution of water to needy areas, remarking that the West was drying up while places around the Great Lakes were “awash in water.” It was around then that a professor at the University of Alabama produced a plan to pipe water out of the Great Lakes into the Sunbelt.

David Naftzger, a former director of the Council of Great Lakes Governors, predicted in 2008 that an eventual water grab is a certainty. “Look at a map showing water shortages and population growth and see how they match up,” Naftzger told the Plain Dealer. “Now look at us and you can see a concern that, as times move on, those areas will be looking at the Great Lakes to bring them water— through either a tanker, pipeline, or natural channels.”

While Congress has the power to repeal the Great Lakes Compact, for now the world’s largest supply of fresh water appears safe. But as a great many commentators have observed, while 20th-century wars were often fought over oil, 21st-century wars will be waged over fresh water.

But even under a worst-case scenario, if some Great Lakes water ends up being diverted later in the century, the advantages enjoyed by the bountiful supply of fresh water enjoyed by just 8 of the 50 states argue strongly for future economic growth.

President Barack Obama has championed a proposal, as of this writing not yet law, that would spend an additional $5 billion over a 10-year period to continue Great Lakes cleanup as part of a plan to revive the lakes’ economic, recreation, and navigational potential. A 2008 Brookings Institute report concluded that such a cleanup would provide Cleveland with an economic boost between $2.1 billion and $3.7 billion with the overall economic benefit to the Great Lakes states estimated at a staggering $100 billion.

The logic is irrefutable. A cleaner Lake Erie for fishing, boating, swimming, and other water activities would not only drive up property values, but would also make the region more desirable for businesses creating jobs and generating wealth. As Greater Cleveland Partnership President, Joe Roman correctly noted, “With 300 miles of shoreline, Cleveland and the rest of Northern Ohio could thrive if we are able to fully realize the economic potential of this tremendous asset.”

Officials in Wisconsin figured this out years before it occurred to those in Greater Cleveland. Four of the world’s 11 largest water technology companies are located in Wisconsin. Milwaukee alone is home to 120 water-related companies. Marquette University Law School now has a water-law curriculum. And planning is underway for a $30 million lake-front headquarters of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Great Lakes Water Institute. Board members and leaders at the Great Lakes Science Center are now engaging in similar water technology efforts, but no one disputes that Greater Cleveland lags behind Milwaukee in planning for a water-based economy of the future.

Toledo Blade

Another significant problem is the troubling growth of toxic algae in Lake Erie and the spread of zebra mussels. The algae colors the water green and can be dangerous to humans, pets, and wildlife. Zebra mussels harm the fishing industry and pollute beaches. These festering problems only underscore the importance of a sizable, federally-funded Great Lakes cleanup plan.

Rebuilding Cleveland’s port as a significant shipping center is proving an even more daunting challenge. the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port authority, a vision of former Mayor Carl Stokes and Council President James Stanton, was created by county voters in 1968 to oversee what was then one of the Great Lakes’ busiest ports. For the first few decades of its existence, the port thrived. For decades, shipping raw materials to make steel was the port’s main business. But even with the steel industry’s decline, an economic impact study in the late 1990s found the port directly accounted for 4,700 jobs, generated $400 million in spending annually, and $64 million in taxes.

But the port also engaged in a obscene amount of over-ambitious thinking, devoting an inordinate amount of time on plans for a World Trade Center, cruise ship and ferry service, an aquarium and lake front retail none of which materialized. Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, shipping at the port declined steadily.

With shipping revenues in a free-fall, the port has struggled to raise its $158 million share of the $600 million tab the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers needs to dredge mountains of muck from the port and Cuyahoga River. Without that dredging—and a place to dump the muck, federal officials have warned that the Cleveland harbor could be shut down by 2015.

By the summer of 2010, Cleveland’s port was in clear crisis mode. the nine-member board fired its director and hired a new one. it scrapped a costly, $1 billion plan to build a new port several miles east of downtown. there was no clear game plan to raise the funds needed for dredging, nor one to revive its slumping shipping business. adding to those woes was the city’s need to secure federal funding to fix a crumbling slope above the river that threatened shipping to sites downstream.

In a series of news stories and editorials, The Plain Dealer outlined the port’s many “immense challenges,” underscored the need for dramatic change, and correctly linked the need for that change with the necessity of the port playing a major role in reviving Greater Cleveland’s economy.

An old, now somewhat trite, saying holds that, in determining the success of a business, the three most important factors are always location, location, and location. The visionary pioneers who settled this territory more than 200 years ago understood that.

Northeast Ohio and, indeed, the entire Great Lakes region, has something the rest of the world desperately needs. What’s more, we have a lot of it.

More than ever before, the fresh water that served us so well in the past represents our best hope for the future.

Bibliography

archives, The Atlantic “Water Summit.” October 29, 2009.

archives, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. 2009.

archives, The Plain Dealer. 1991–2010.

Miller, Carol Poh and Robert Wheeler. Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796–1996. 2nd edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Rose, William Ganson. Cleveland: The Making of a City. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1950. reprinted with a new introduction. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1990.

Van Tassel, David D. and John J. Grabowski. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. 2nd edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Wallen, James. Cleveland’s Golden Story: A Chronicle of Hearts that Hoped, Minds that Planned and Hands that Toiled, to Make a City “Great and Glorious.” Cleveland: William Taylor & Son, 1920.

Water: Our Thirsty World. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, April 2010.

Further resources: http://www.great-lakes.net/teach/about/