Newton D. Baker: Cleveland’s Greatest Mayor

By Thomas Suddes

Approaching age 30, Newton D. Baker, a West Virginian educated at two of America’s finest universities, came to Cleveland in 1899. Baker was enormously gifted. And Baker was searching for opportunity. He found it in Cleveland, like so many before him, like so many since.

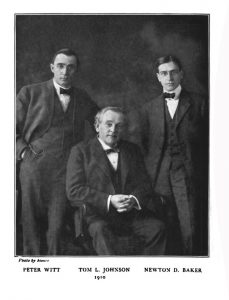

And in time, Baker became a protégé of perhaps Cleveland’s best-known mayor, the great reformer Tom L. Johnson, mayor from 1899 to 1909.

Baker also became the executor of Johnson’s political legacy, fashioning it into forms and philosophies that characterize Cleveland’s government and political culture even today.

Johnson’s vision and the battles he waged on behalf of ordinary Clevelanders likely make Johnson better-known today than Newton Diehl Baker is.

But in terms of follow-through, in terms of shaping the Ohio Constitution into what it is now, and fashioning a city charter to give Clevelanders more freedom to govern themselves than ever before, Baker, arguably, was Cleveland’s greatest mayor. Johnson had the dream, but Baker made much of it real.

Baker didn’t just share Johnson’s outlook. Baker made Johnson’s hopes concrete by deploying exceptional gifts for advocacy in the courtroom. Little wonder that Tom Johnson made Newton Baker first assistant law director for Cleveland.

Johnson, in his autobiography, lavishly praised Newton Baker for his many talents, but especially Baker’s legal acumen:

Though [Baker in 1903] was the youngest of us all, [he] was really the head of the Cabinet and adviser to us all. As a lawyer, he was pitted against the biggest lawyers in the State. No other City Solicitor ever had the same number of cases crowded into his office in the same length of time or so large a crop of injunctions to respond to, and in my judgment no other man in the State could have done the work so well.1

Baker, like Johnson, was an idealist. Baker’s idealism recommended him to The Plain Dealer when it endorsed him for mayor in 1911:

“[Baker’s] critics … call him a dreamer. … [But] the progress of the world is written in the dreams of dreamers. … Unless a man is a dreamer, he is a plodder. .. . Plodders have their place of course, but no wide-awake city wants one for mayor.”2

Three times the voters of Cleveland elected Baker their city solicitor (a job today called city law director). “Baker’s job,” Archer Shaw of The Plain Dealer wrote, “was to find the law to support the ambitious designs of [Johnson].” That is, Baker in effect channeled through litigation Johnson’s dreams for Cleveland: And “the most important battle the Johnson-Baker partnership waged was municipal operation of Cleveland’s street railroads.”3 Little wonder, then, that after Johnson’s 1911 death, Baker inherited “the mantle of chief [Cleveland reformer].”4

How did Baker appear to the colleagues and voters – and adversaries – who encountered him? The New York Tribune, profiling Baker when Wilson named him secretary of War, said Baker was “a slim little man with a fighting jaw and a whimsical eye. … He is possessed of a clear analytical mind which has been called one of the most intellectual in the country.”5 He was also “youthful in appearance, he was an excellent extemporaneous speaker and seldom wrote out even a major address.”6 In a 1916 study, published just after Baker had left the mayor’s office, Western Reserve’s C.C. Arbuthnot wrote this about Baker: “A cultivated taste and a wide intellectual outlook, united with a catholicity in judgment, made the scholar in the mayor’s office a source of more real gratification to many of his fellow townsmen than malls and monumental buildings.” 7

Baker’s popularity crossed party lines. For example, in 1909, even as the voters of Cleveland ousted Johnson from the mayor’s office and replaced him with Republican brewer Hermann Behr, those same voters re-elected Baker, Tom Johnson’s lieutenant and fellow Democrat, as Cleveland’s city solicitor. “Baker,” Shaw wrote, “was the only Democrat [that year] to survive the Republican onslaught.”8

The path from Martinsburg, W.Va., Baker’s hometown, to Cleveland, wasn’t direct, but in retrospect it looks preordained. Before coming to Cleveland, Baker had landed a patronage job as assistant to Postmaster General William L. Wilson, a West Virginian who from 1895 to 1897 was in Grover Cleveland’s Cabinet.9 In mid-1897, after Canton Republican William McKinley succeeded Democrat Cleveland, Baker took an Atlantic voyage. One of Baker’s shipmates was a highly successful Democratic lawyer from Cleveland, Martin A. Foran (1844-1921).10 In the 1880s, Foran served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was later elected a judge of Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court.

After Baker returned to the United States from his voyage, he sought a bigger arena than Martinsburg (and West Virginia) in which to practice law, such as Pittsburgh or Cleveland. Baker was, his biographer recorded, “impressed with the public spirit of Cleveland; everyone seemed to be aware of the importance of good government and public improvement.”11

Meanwhile, Foran asked another Cleveland lawyer, who happened to have been a Baker classmate at Johns Hopkins – Frederic C. Howe – to recommend an able lawyer to join Foran’s practice.12 (Howe was more than just a classmate of Baker’s – he was also a fraternity brother to Baker.)13 Howe suggested Baker; Foran remembered Baker from their voyage – and hired him.

When Newton Baker arrived in Cleveland to practice law, he was far from alone in seeking his fortune in the lakeside metropolis. Greater Cleveland’s pulsing industrial might arguably made the city and its environs that era’s Silicon Valley, albeit a Silicon Valley that produced steel and chemicals and, perhaps above all, the machine tools that made Ohio one of the world’s manufacturing giants. The city and its enterprises were exploding with growth.

Population statistics offer dramatic evidence of that growth. In 1890, roughly a decade before Baker came to in Cleveland, the city had about 262,000 residents. The 1900 Census, taken the year after Baker settled in Cleveland, found that the city now housed more than 381,000 men, women and children. That is, in 10 years, the city’s population had grown 45 percent. “Cleveland,” historian Thomas Campbell wrote, “had reached the flowering stage of its industrial development.”

Campbell, biographer of another Western Reserve newcomer, Daniel Morgan of Southern Ohio’s Jackson County, described Cleveland around 1900 this way:

Thousands of people had poured in … Most were bewildered immigrants, speaking a babel of tongues … But not all had crossed the seas to make their home in Cleveland. Many … were … country folk leaving farms and small towns. … All of them, immigrants and migrants alike, were the new pioneers of the twentieth century … [in a] congested conglomeration of factories and office buildings, homes and slums, filled with a noisy, restless tide of humanity.14

It was, incidentally, that human tsunami that helped prompt the birth of Cleveland’s settlement house movement, which aimed to assimilate newcomers into the city, and the adult education movement, which aimed to educate working-class Clevelanders for jobs and citizenship.

Appropriately, adult education was a key ingredient in Newton Baker’s recipe for a better Cleveland. In the 1920s, after Baker had been Cleveland’s mayor and Wilson’s secretary of War, Baker was the heart and soul of Cleveland College, which was dedicated to adult education. Baker considered Cleveland College “the most significant educational project with which he was connected.”15

Daniel Morgan, from Jackson County’s Welsh-American village of Oak Hill, got to Cleveland in 1901 after graduating from Harvard law school. In time, Morgan would help Newton Baker write Cleveland’s charter. Still later, Morgan became Cleveland’s second city manager and, toward the end of his life, a judge of the Ohio Court of Appeals (8th District).

Morgan, with Baker, were two of the stars in a galaxy whose sun was Tom L. Johnson, born in Kentucky in 1854. Another person in the Johnson cohort was Harris Cooley, born in 1857 in what was then Royalton Township. Cooley was a Disciples of Christ minister who later served in Johnson’s Cabinet

Also orbiting Johnson was Peter Witt. Born in Cleveland in 1869, Witt, like Johnson, was a disciple of philosopher Henry George.

George (1839-1897) wrote Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Causes of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth, published in 1879. Reduced to essentials, George’s book called for a Single Tax on land to capture, for public benefit, the unearned increases in land’s value due to public improvements and economic growth.16 It is hard now to recapture the excitement generated by George’s Single Tax idea. Those who believed in the Single Tax claimed it would end poverty. The Single Tax captivated Tom L. Johnson: “[Johnson] had gotten an idea – the idea that poverty, unemployment, slums, disease, crime – could be eliminated.”17

Newton Baker was Johnson’s acolyte. Baker appreciated Henry George’s war on privilege. But Baker didn’t share Johnson’s enthusiasm for the Single Tax because, “unlike Johnson, [Baker] never believed there could be wholesale application of single-tax principles to the old and established society in which he lived.”18

Indeed, Baker’s personal library, at least in the 1930s, lacked a copy of Progress and Poverty (though a biography of Henry George, by George’s son, was.)19 That is, Baker was no radical. He was “basically an aristocrat who had little in common,” for instance, “with [Peter] Witt’s savage attacks, ruthless sarcasm, and lack of refinement.”20 In fact, according to another Baker biographer, Baker “consistently drew support from constructive conservatives, both Republican and Democratic, in Cleveland. [He was] deeply committed to stability and order.”21

If Baker were an “aristocrat,” he was an aristocrat of the liberal persuasion. Consider what Baker said in the 1920s about the liberalism he had always embraced in political life:

Liberalism is a state of mind and not a creed. A liberal uses his fellow man for their own benefit and not for his own. He judges political purposes by their effect on the common good, and he has in his mind’s eye, as the ultimate object of his concern “the forgotten man,” remote, obscure and inaudible in high places. Liberalism of this quality is imperishable and it has many brave services yet to perform for the American people.22

Programmatically, the 1912 Democratic state platform may be as good a guide as there is to the collective thinking of that era’s Ohio Democrats – and Newton D. Baker was then a member of the Ohio Democratic State Central Committee:

The [Ohio] Democratic party stands, first, for the restoration of the government to the people through direct legislation and through the simplification of the machinery of government so the people may adequately express themselves; and, second, for legislation looking to the abolition of privilege and to the restoration of equal opportunity to all.23

It was Foran who had told Tom L. Johnson about Baker, according to Hoyt Landon Warner: “Johnson, immediately attracted to Baker, brought him into his administration first as legal adviser to a tax boards and then, when an opening occurred, as an assistant law director.” 24 Baker had already done “social and civic work” at the urging of Howe, who’d “invited [Baker] to a join a social service club at the YMCA, which conducted a vigorous program for the welfare of children and workingmen.”25 Howe later recalled:

The brilliant promise of Baker’s student days at Johns Hopkins was more than fulfilled in those early years of his maturity [in Tom Johnson’s Cleveland]. He was a splendid speaker, fluent, resourceful, and adaptable. Richly endowed mentally he seemed never to know what it was to be tired. He did his work easily, mastered intricate legal subjects quickly, and had time for wide and carefully selected reading.26

Besides Baker and Cooley, Morgan and Witt, others in Tom L. Johnson’s inner circle included Painesville native Charles W. Stage, a lawyer who served in Baker’s mayoral administration; Howe, born in Pennsylvania in 1867, a Cleveland City Council member allied to Johnson during Johnson’s mayoralty, who’d recommended Baker to Martin Foran; and Massachusetts-born Edward W. Bemis, who reformed Cleveland’s waterworks when Johnson was mayor. Coincidentally, Howe and Bemis, like Baker, held degrees from Johns Hopkins University, founded in 1876 as the first American research university, where future President Woodrow Wilson, who later figures large in the Newton Baker story, earned a Ph.D. in 1886.

In Cleveland, as in other big cities, a cauldron of industrial expansion and population growth brought with it enormous challenges. Some were obvious: Growth could easily outpace existing urban services (streets, sewers and drains, gas-, electricity- and telephone services, public transportation). But ruthless, determined monopolists controlled the immense sums of capital required to add or expand urban services. That stark fact created a conflict of interest between elected officials eager to provide their cities with public services – and the monopolists who owned utilities that monopolized extortionately priced public services.

Worse, urban service monopolists had an end-run in case a given cities officials scorned bribes and blackmail. In that case, special interests could quietly run (and lavishly finance) pet candidates. Or, at less risk, though at greater cost, special interests could grease the Ohio General Assembly to rip local decision- making away from local officials.

That was done through appropriately named “ripper” bills. In 1902, for instance, the Ohio General Assembly passed a bill stripping the mayor of Toledo (Sam “Golden Rule” Jones) of power over that city’s police board and police court. “And that was not the only ripper bill passed in the 1902 session. The tax boards of the cities were shifted from local to state control, and Cleveland also had its park board metamorphosed.”27

Earlier, in 1896, the General Assembly flaunted an especially smelly example of interference in local matters. Former Gov. Joseph B. Foraker, a Cincinnati Republican and major lawyer-lobbyist, engineered General Assembly passage of the “notorious Rogers Law,” which benefited the Cincinnati Street Railway Co., the city’s streetcar monopoly, by allowing Cincinnati officials to extend – for 50 years – the streetcar company’s franchise.

Among those who denounced the Rogers Law was the great muckraker Lincoln Steffens. He denounced the bill not only for what it was, but for what it demonstrated about how the marriage of political corruption and private greed were trampled at the Ohio Statehouse:

The plain, undeniable, open facts are that the Legislature of 1896 which elected Foraker to the United States Senate was led by the Senator … to pass in the interest of the traction company a bill which granted privileges so unpopular that public opinion required a repeal in the next Legislature of 1898. In other words, this man, who by his eloquence won the faith of his people, betrayed them for some reason to those interests which were corrupting the government in order to get privileges from it.28

Worse, Foraker later “represented the transit firm before [state officials] and succeeded in winning a $285,000 reduction in the company’s tax valuation.”29 Even more outrageously, after courts ruled that the Rogers Law was blatantly unconstitutional, General Assembly members in thrall to the teeming Statehouse traction lobby tried to pass a “curative provision” to overturn the court’s ruling and thus reinstate the Cincinnati Street Railway’s sweet, 50-year franchise.

This was the seamy Statehouse reality that reformers such as Johnson and Baker had to confront in Columbus. That so-called curative law, a bid “to restore such an ‘iniquitous franchise’ aroused the ire of [Newton] Baker and [Tom] Johnson, who delivered tirades against the curative proposal.”30 Foraker’s maneuvers demonstrated how it was that in that era of Ohio history, a corrupt legislature could be bought and sold by corporate interests in end-runs around good government reformers in Ohio’s city halls.

Baker later described the difficulties that Ohio cities faced at the Statehouse before home rule:

We had a legislature … which we called “The Garbage Legislature.” Men trafficked in votes upon legislation in the lobby of a hotel immediately across from the State House, and men were heard to weep and complain because the amount they had gotten for their vote was less than some associate legislator had gotten.31

In 1912, Baker wrote the Ohio Constitution’s municipal home rule amendment. And Baker helped form the commission that wrote Cleveland’s first home rule charter, which the city’s voters approved in 1913.32

A few years later, in 1914, after Ohio had empowered its cities and villages, Baker said this of the privately owned utilities whose excesses helped get home rule ratified: “All sincere and fair observers put their fingers upon the public utilities corporations in the city as at least the greatest contributing cause of the corruption of the American city.”33

Such interference by monopolies and a shady legislature that sparked Cleveland’s battle, on its behalf, and on behalf of Ohio’s other big cities, to determine local policies locally: Home rule.

Any discussion of Baker’s commitment to home rule needs to be guided by an important aspect of Baker’s thinking. Interference with the affairs of Cleveland by the General Assembly was, wrong, yes, and even if it hadn’t been wrong it was done for all the wrong reasons.

But what Baker really opposed was the strait-jacketing of Cleveland (or any community) with one-size-fits-all demands from a centralized government. His concerns were not so much philosophical as they were practical: Central imposition of uniform patterns was simply unworkable.

Baker said that cities should be experiment stations, as, for instance, were the agricultural experiment stations Congress authorized in every state by the Hatch Act of 1887, signed by President Grover Cleveland. The act authorized grants to every land-grant college – Ohio’s is Ohio State University – to promote experimentation and disseminate the results of research.

For instance, writing to his friend John H. Clarke in March 1916, Baker said, “The problems of democracy have to be worked out in experiment stations rather than by universal applications, so that I regard Cleveland and Ohio as a more hopeful place to do things than in any national station whatsoever.”34 Thus, Baker, “during his years of struggle with officials at the state capital in Columbus… developed a profound distrust of government beyond the local or municipal level.”35

Experimenting locally meant cutting fetters clamped on at the Statehouse. In 1916, Mayo Fesler of the Cleveland Civic League sketched the objectives Baker and other urban reformers had in prying a home rule amendment from Ohio’s 1912 Ohio Constitutional Convention.

Cities and villages, Fesler wrote, wanted freedom from General Assembly interference. They wanted to exercise, themselves, “all powers of local self- government.” And they wanted power to determine their own specific forms of city or village government by writing, if they chose, their own charters, as Cleveland’s voters did in June 1913.

In 1916, just three years after the home rule amendment had become part of the Ohio Constitution, Fesler found that court rulings had advanced (or at least not impeded) those reform objectives.36 Interestingly, Fesler wrote that municipal home rule had “made Ohio a municipal laboratory … for promoting economy and business-like efficiency” – the very experiment stations that Newton Baker wanted Ohio’s cities and villages to become.

So what, before and after the 1912 convention, did Newton Diehl Baker do to realize the dreams of Tom L. Johnson and advance of the hopes of rank-and- file Clevelanders?

Looking back, Western Reserve University’s Arbuthnot observed in 1916 that, with the exception of Hermann Baehr’s two years in the mayor’s office, Cleveland “has been for fifteen years under the influence of the [Tom] Johnson school of politics.”37

True, Arbuthnot found that, financially, Cleveland was in a deficit. But Arbuthnot attributed that not to municipal mismanagement but to the revenue shortages faced by many American cities. But Arbuthnot made another observation, as sound today as it was in 1916: “The growth in civic necessities has been more rapid than the growth in civic consciousness.”38 In short, voters were willing to demand and use new city services, but were also reluctant to pay for them. Too, the Ohio General Assembly, as was its right under the home rule amendment, had limited city and village taxation via the so-called Smith law.

Offsetting those problems was completion by Baker of a new (today’s) City Hall; smooth implementation of the so-called Tayler plan regulating mass transit fares and service in the city; improvements in the East Ohio Gas Co.’s service inside Cleveland; and Baker’s policy of “seeking even in other cities for the best [administrative] talent available.” 39

Baker’s record of achievements as Cleveland’s mayor began in 1911 when voters elected him rather than the Republican candidate, Frank G. Hogen. (Hogan had been in the mayoral Cabinet of Hermann Baehr, who’d unseated Tom Johnson in 1909.)

Candidate Baker “made the chief issue of the [1911] campaign” the approval of a $2 million Cleveland city bond issue whose proceeds would expand what became known as Muny Light (today’s Cleveland Public Power. The Muny Light expansion “cut the electric-light rate to three cents.”

In the 1911 mayoral campaign, the primacy of the public vs. power debate was demonstrated by what historian Hoyt Landon Warner characterized as the campaign’s climax. It was a debate between Baker and Samuel Scovill, president of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co., now a tentacle of Akron-based FirstEnergyCorp.

Baker and Scovill faced each other in the auditorium of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. Baker, Warner wrote, “concluded with a characteristic dramatic touch, ‘I am in the house of have. I appeal on behalf of the house of want – for justice.’ ”40

Newton Diehl Baker’s record as mayor of Cleveland was a cavalcade of accomplishments, previewed by a 1911 campaign that copied some of Tom Johnson’s campaign techniques, including Johnson’s tent meetings.41 Baker’s 1911 victory, by a plurality of 17,738 votes, “was the largest received by a candidate for mayor up to that time.”42

One post-victory priority was perfecting home rule for Ohio cities by amending the Ohio Constitution, something Ohio’s (male) voters did in 1912; they approved many proposals of a state constitutional convention, including a home rule amendment. (Baker collaborated with another Ohio municipal reformer, Toledo’s Brand Whitlock in composing the amendment.)43

With the home rule amendment ratified, according to Baker biographer Cramer, Baker became known as the “three-cent mayor.” That is, Baker wanted “three-cent streetcar fares, [lighting], dances and fish,” the latter referring to a municipal fishery Baker supported to help consumers when prices climbed in the private market.44

In 1913, Baker won re-election. He captured a second mayoral term by besting GOP challenger, Harry L. Davis, whom Warner, the historian of Ohio Progressivism, described as “a politician of small caliber.”45 Davis was backed by the Cleveland Leader, owned by, and voice of, Dan Hanna, son of Mark.46 The Cleveland Press, in endorsing Baker, said, “Newton Baker has gone briskly and capably about his job of being a good mayor. … He has been part of every forward movement the people of Cleveland have made.”47

Still, as Cramer recorded, Baker beat Davis by just 3,258 votes in 1913, a much smaller margin than Baker had accumulated in 1911 against Hogen. Interestingly, Baker received “decisive nonpartisan support [from] independent Republicans,” likely the result of Baker’s nonpartisanship.48 As mayor, Cramer concluded, “had given Cleveland both dignified and distinguished service,” which had contributed to Baker’s re-election victory.49 (Nevertheless, as Cramer also observed, “the position [of mayor] in City Hall was destined to be the last elective office held by the ‘Big Little Mayor.’ ”)50

Muny Light opened in 1914. It was, according to Cramer, “the largest in the nation at the time,” and Baker later estimated that over the plant’s first eight years, “it saved the people of Cleveland almost fourteen million dollars.”51

Western Reserve’s Arbuthnot made it clear that, in the absence of better accounting data, it was unclear if Muny Light – which began operating in July 1914 and by 1916 had 15,000 customers – was operating in the red or operating in the black.

Foreshadowing what would become nearly a century of attacks on public power, Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co., which had 75,000 Cleveland customers at the time Arbuthnot wrote, claimed Muny Light was operating in the red. Muny Light, Arbuthnot reported, claimed it had accrued a $33,000 profit during the first seven months of 1915. Undeterred, the Illuminating Co. claimed Muny Light had incurred an $81,000 loss during that same period that was masked by Muny Light accounting that, intentionally or not, the Illuminating Co. claimed was incorrect.52

Baker’s appointment of Peter Witt as traction commissioner was considered a major success, as were such Baker accomplishments as a subsidized municipal orchestra, new city piers, and the realization of some features – sadly, not all of them – of Daniel Burnham’s Group Plan for the Mall.53

On the other side of the ledger, an adulterous affair led to the removal of police chief Fred Kohler, and for reasons that now seem inexplicable, Baker failed to see the urgency of securing for Cleveland a first-class and salubrious water supply, although in time he attacked that problem.54

In or out of City Hall, Baker’s prominence and accomplishments made him a sparkplug of the Democratic Party’s reform wing. From youth until death, Baker was among Democrats’ most revered and senior national statesmen, even if, in time, Baker broke with the New Deal outlook of his fellow Democrat and longtime acquaintance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s brand of liberalism wasn’t Baker’s brand. One historian said that Baker, like many of that era’s other conservative Democrats, might best be described as “internationalist in foreign outlook and conservative in domestic philosophy.”55

Baker didn’t seek a third term as mayor, left office on Jan. 1, 1916 – and, soon after, Woodrow Wilson named him secretary of War.

Today a Greater Clevelander knows much about Newton Baker, that’s likelier due not to Baker’s illustrious civic leadership but, say, to the 800-lawyer Cleveland-based BakerHostetler law firm, which Baker helped found. Or, if a Clevelander is an Ohio State University alumnus, perhaps he or she knows that an Ohio State dormitory, Baker Hall, which opened in 1940 on the university’s south campus, several years after Baker died, is named for Baker. He was once an Ohio State trustee.

Fame is fleeting, but accomplishments last. It is only a slight exaggeration to say of Baker and of the Cleveland and Ohio he helped create, as the epitaph of the British architect Christopher Wren says of Wren in Wren’s St. Paul’s Cathedral: “If you seek his monument, look around.” In Baker’s case, that means looking around Greater Cleveland – and looking around Ohio, especially at the state’s constitutional and statutory framework for city and village self- government.

On the roster of political godparents of today’s Cleveland, Johnson arguably has primacy over Baker, at least in public memory. But Baker indisputably was Tom Johnson’s heir.

Baker came to believe, though, that not all the reforms Progressives ballyhooed in Ohio in 1912 were necessarily unqualified plusses. Among reforms Baker later believed had been “tried and found of less value in practice” were the initiative, referendum, recall, non-partisan primaries, the commission form of city government and proportional representation.56 Ohio authorizes the initiative and referendum, and grants cities and villages, if they wish, the recall, non-partisan elections, a commission form of local government and proportional representation (though “commission” municipalities are few, and proportional representation now appears to be absent from Ohio).

Baker, writing in the 1920s, a decade after being mayor, said that home rule had made a salutary difference in local government in Ohio:

Many cities have made and re-made their own charters and a series of informing experiments has been made in municipal institutions, so that city government is freer from bossism, more responsive to popular control and more efficient than it used to be. With these changes has come the full acceptance of the program of municipal activity for which radicals used to contend – better public schools, parks, bath houses and public control of public utility monopolies.57

Early in his days at Cleveland City Hall, Baker’s reputation for sturdy liberalism in the face of such right-leaning Ohio Democrats as Gov. Judson Harmon, a railroad lawyer from Cincinnati, evoked at least one published call, in a letter to the editor of the influential North American Review, for Baker’s nomination for president in 1916 in lieu of incumbent Democrat Wilson, seen by the letter-writer as too conservative:

In the fight for a [reformed] constitution in Ohio the master hand and master mind of Newton D. Baker could be traced at every turn, – the same Baker that fought through fifty-seven injunctions from the lowest court in Ohio up to the Supreme Court of the United States to fix forever the principle that every American city has a right to its own streets?58

On the social front, Newton Baker, first as a Johnson lieutenant, then as mayor of Cleveland, finally as a post-mayoral Clevelander, promoted the idea of public responsibility for enculturation (or, in the case of immigrants, acculturation) by, for example, as noted above, establishing Cleveland College as a school for adult learners.

Cleveland College was part of what is now Case Western Reserve University. The college’s founding was a huge boost for Greater Clevelanders: Before the college opened, “Cleveland didn’t have a municipal or quasi-municipal institution of higher education. In contrast … [there were] … 11 municipal colleges or universities [elsewhere] … including Ohio’s Akron, Cincinnati, and Toledo universities.”59

Baker’s lasting national prominence was such that, even years after leaving Cleveland City Hall, and more than a decade after Wilson’s presidency ended, he was a potential Democratic presidential nominee. That fact, often overlooked today, earned mention in a book of A.J. Liebling’s essays published a decade later, in the 1940s.60

Liebling’s New Yorker profile of newspaper mogul Roy Howard of the Scripps Howard chain (which included The Cleveland Press) recorded that Howard had been part of a “stop (Franklin) Roosevelt” movement at the 1932 Democratic National Convention.

Howard’s take on Baker’s potential for landing the nomination in lieu of FDR: If Roosevelt’s convention foes managed to stop Roosevelt, that might eventuate in Baker’s nomination. (And Baker, Liebling tartly noted, was “incidentally, general counsel for the Scripps-Howard newspapers.”)

Not everyone was either persuaded by Baker’s eloquence or edified by his stated idealism. For example, in a slashing 1932 article, the great liberal journalist Oswald Garrison Villard denounced Baker in every mood and tense:

Just another politician and orator without fixed principles, veering to the wind if necessity arises or there is an opportunity to take office or make money – this is Newton D. Baker. … He started out as an idealist of the finest type; he can clothe his ideals in beautiful language and touching generalities. … Then he can and will forsake them whenever expediency counsels.61

After leaving Wilson’s Cabinet, Baker was not simply a “prominent lawyer” or a “former mayor.” In life, as in politics, Baker was not all one thing or the other, which was evidently part of what irked Villard. Baker’s biographer wrote:

Baker believed sincerely in the ultimate objectives of the Progressive Movement but often disagreed with his colleagues on the most suitable means to achieve them. With [Tom L.] Johnson he agreed in the soundness of the anti-privilege position taken by Henry George; unlike Johnson he never believed there could be a wholesale application of single-tax principles to the old and established society in which he lived. There was a lot of Southern tradition in Baker, and it sometimes seemed contradictory that this lawyer and scholar should espouse the cause of the people and take an abiding interest in modern sociology and politics. But he had a warm heart along with his cool head, and the heart was moved by Tom Johnson just as it was to be excited later by Woodrow Wilson.62

After World War I, Baker helped build BakerHostetler; tended to personal investments; and further burnished his reputation as a superb advocate for his clients and causes. And Baker, like his close friend John Clarke, who in 1916 Wilson had named to the U.S. Supreme Court , was an ardent League of Nations supporter, a cause that was a moving force in Wilson’s presidency, though that quest ended in failure.63 (To Villard’s disgust, Baker later abandoned his call for U.S. membership in the League.)

Baker’s plea for League membership, given in a speech to the 1924 Democratic National Convention. “was remembered by Adlai Stevenson as the greatest speech he had ever heard.”64 It “enhanced [Baker’s] stature and cemented his image as heir apparent to the [Wilson] mantle.”65

Baker’s great gifts as a courtroom advocate were both a plus and a minus to after he returned to private life while remaining active in Democratic Party affairs. For instance, though it may seem paradoxical given Baker’s support for and identification with what’s now Cleveland Public Power, “Baker’s greatest handicap [in the 1930s] with Progressives was his identification [as a lawyer] with private utility interests.”

A particularly piquant instance was Baker’s legal representation of Appalachian Power Company, today’s American Electric Power Co., in what was known as the New River Case, a 15-year court fight over whether federal law could require Appalachian to secure a Federal Power Commission license to dam the New River.66 And support of public power (as opposed to private power) was a key test of political authenticity to the Progressives who by then were key players in Democratic presidential nomination campaigns

One such Progressive, Judson King, of the National Popular Government League, said this of Baker: “Baker has taken a long stray to the right since I used to know him back in 1906 to 1910 as the right arm of Tom Johnson.”67

Moreover, Baker was also a supporter of the so-called open shop, a fact he had confirmed in 1922 correspondence with Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor.68 An “open shop” refers to a workplace that does not require an employee to join a labor union as a condition of his or her employment in that job. The Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, of which Baker had been president, favored the open shop.

Franklin Roosevelt, not Newton Baker, was Democrat’s 1932 nominee, and FDR handily won the presidency, then a second term in 1936, despite the misgivings of Baker and other conservative Democrats. FDR’s policies concerned Baker to the point that he confided in his close (maybe closest) friend, retired Justice Clarke, that Roosevelt might not get Baker’s vote in November 1936. In a letter to Clarke, who had retired to San Diego, Baker indicted the New Deal “for its ‘frightful extravagance,’ for the ‘wickedness of a political administration of these government favors,’ for … ‘coercion.’ … ‘Our present government is a government by propaganda and terrorism.’ ”69 But as the 1936 election neared, Baker hinted to Clarke that Roosevelt might have improved his standing with Baker, if slightly:

If I am sure the President will be re-elected, I shall not vote for him. If I think there is any doubt I shall … If I could have my way, Roosevelt would be reelected by one vote and the House of Representatives would be so closely divided that one sensible and courageous man would hold the balance of power.70

Newton Baker’s 1936 take on FDR had an uncanny resemblance to the plaintive remark of a New York Democrat disillusioned in 1896 by another perceived Democratic radical, William Jennings Bryant: “I was a Democrat before the …convention, and I am a Democrat still – very still.”71

Footnotes

1 Archer H. Shaw, “New War secretary as his neighbors know him,” The New York Times (March 12, 1916).

2 “Newton D. Baker, Dreamer,” The Plain Dealer, Oct. 30, 1911.

3 Beaver, 4.

4 Ibid.

5 Frederick Palmer, Newton D. Baker, America at War (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1931), 7, citing the New York Tribune, March 7, 1916.

6 Beaver, 7.

7 Arbuthnot, 240.

8 Ibid.

9 C. H. Cramer , Newton D. Baker: A Biography (Cleveland: World Publishing Co. , 1961), 26-29.

10 Ibid. 29-30; Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present, s.v. “Foran, Martin Ambrose. ”

11 Cramer, op. cit., 30.

12 Howe,1867-1940, a key ally of Tom L. Johnson, was later elected to the Cleveland City Council and the Ohio Senate: Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, s.v. “Howe, Frederic C.”

13 Warner, op. cit., 63.

14 Thomas F. Campbell, Daniel E. Morgan, 1877-1949, The Good Citizen in Politics (Cleveland: The Press of Western Reserve University, 1966), 10.

15 C. H. Cramer , Newton D. Baker, a Biography (Cleveland: W orld Publishing Co. , 1961), 198.

16 American National Biography, s.v. “George, Henry.”

17 Cramer , C. H. , Newton D. Baker, a Biography (Cleveland: W orld Publishing Co. , 1961), 36.

18 Ibid., 41.

19 Willis Thornton, Newton D. Baker and His Books (Cleveland, The Press of Western Reserve University, 1954), 71.

20 Cramer, op. cit., 41.

21 Beaver, op. cit., 5.

22 “Where Are the Pre-War Radicals?” The Survey 55 ( Feb. 1, 1926): 557.

23 “Ohio Democratic Platform, 1912,” Ohio Almanac and Hand-Book of Information (1914), 222-223. 24 Ibid.

25 Ibid..

26 Frederic C. Howe, The Confessions of a Reformer (New Y ork: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 190.

27 Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press for the Ohio Historical Society, 1964), 36, 106.

28 Lincoln Steffens, The Struggle for Self-Government, Being an Attempt to Trace American Political Corruption to Its Sources in Six States in the United States, with a Dedication to the Czar (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1906), 176-177.

29 Robert H. Bremner, “Asa S. Bushnell, 1896-1900,” in The Governors of Ohio (Columbus: The Ohio Historical Society, 1954), 133.

30 Warner, op. cit., 112.

31 Baker, “Municipal Ownership,” op. cit., 190.

32 The Dictionary of Cleveland Biography, s. v . “Baker , Newton Diehl. ”

33 Newton D. Baker, “Municipal Ownership,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 57 (January 1915): 189. This number of the Annals published the Proceedings of the Conference of American Mayors on Public Policies as to Municipal Utilities, held in Philadelphia on Nov. 13 and Nov. 14, 1914.

34 Beaver, 1.

35 Beaver, 5.

36 Mayo Fesler, “The Progress of Municipal Home Rule in Ohio” National Municipal Review (v. 5, no. 2) April 1916, 242.

37 C.C. Arbuthnot, “Mayor Baker’s Administration in Cleveland” National Municipal Review (v. 5, no. 2), April 1916, 226.

38 Ibid., 227.

39 Ibid.

40 Warner, op. cit., 302.

41 Cramer, 47.

42 Ibid., 48-49.

43 Ibid., 49-50.

44 Ibid., 50-51.

45 Ibid.. 444; Davis (1878-1950) eventually did win election as mayor, and in 1920 he was elected governor of Ohio for one term (1921-1923); Davis was mayor for a fourth term 1933 and 1934: The Governors of Ohio (Columbus: Ohio Historical Society, 1954), 163-165. Davis tried an unsuccessful gubernatorial comeback in 1924.

46 Warner, op. cit., and Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, s.v., “Cleveland Leader.”

47 “What the issue is,” The Cleveland Press, Nov. 1, 1913.

48 Cramer, op. cit., 58 49 Ibid., 57.

50 Ibid., 59.

51 Ibid., 51.

52 Arbuthnot, 239. 53 Ibid., 52-54.

54 Ibid., 55-56.

55 Elliott A. Rosen, “Baker on the Fifth Ballot? The Democratic Alternative: 1932,” Ohio History 75 (autumn 1965): 229. Though the idea of Democrats as “business conservatives” may appear paradoxical, that would aptly characterize Grover Cleveland’s Democratic administration, in whose Post Office Department Baker served. And in 1896, one of Baker’s closest friends, future U.S. Supreme Court Justice John H. Clarke, likewise a Greater Cleveland progressive, declined to support the pro-silver inflationary Democratic presidential ticket led by William Jennings Bryant but instead backed the National Democratic (”gold Democrat”) ticket led by John M. Palmer; so, incidentally, did

Wilson; see David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, “Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900,” Independent Review 4 (spring 2000): 568, 569.

56 “Where Are the Pre-War Radicals?” op. cit., 556.

57 Ibid.

58 John McF. Howie, “The Master Hand and Mind of Newton D. Baker,” North American Review 204 (August 1916), 319.

59 Thomas Suddes, “The Adult Education Tradition in Greater Cleveland,” 11, in Teaching Cleveland, citing John P . Dyer , Ivory T owers in the Marketplace: The Evening College in American Education (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1956), 35.

60 A. J. Liebling, The T elephone Booth Indian (Garden City , N. Y . : Doubleda y , Doran and Co . , 1942), 245- 246.

61 Oswald Garrison Villard, “Presidential Possibilities VII: Newton D. Baker – Just Another Politician,” The Nation (April 13, 1932), 414.

62 Cramer, op. cit., 41-42.

63 Clarke, a co-owner of the Youngstown Vindicator, resigned in1922 from his lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court in order to devote himself full-time to campaigning for U.S. membership in the League.

64 Daniel R. Beaver, “Baker, Newton Diehl,” in American National Biography Online. Stevenson, later governor of Illinois, was the Democratic nominee for president in 1952 and 1956, and a grandson of Adlai E. Stevenson, vice president of the United States from 1893 to 1897, elected on fellow Democrat Grover Cleveland’s 1892 Democratic presidential ticket.

65 Beaver, op. cit.

66 Rosen, op. cit., 237. In December 1940 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-2 (one justice recused himself) that Appalachian Electric Power Co., a unit of American Electric Power was indeed required to get a Federal Power Commission license for a dam on the New River, a watercourse in Virginia and West Virginia. The ruling represented a loss for the company, Baker’s client. Moreover, the ruling vastly broadened federal jurisdiction over hydroelectric projects generally.

67 Ibid., 238.

68 Ibid., 239.

69 Hoyt Landon W arner , The Life of Mr . Justice Clarke: A Testament to the Power of Liberal Dissent in America (Cleveland: Western Reserve University Press, 1959), 192.

70 Carl Wittke, “Mr. Justice Clarke – A Supreme Court Judge in Retirement,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 36 (June 1949): 44. Emphasis is in the original.

71 New York Gov. David B. Hill, letter dated Sept. 12, 1896, to New York state Supreme Court Justice Hamilton Ward, in Hamilton Ward Jr., Life and Speeches of Hamilton Ward, 1829-1898 (Buffalo: Press of A.H. Morey, 1902), 399.

References

Arbuthnot, C.C., “Mayor Baker’s Administration in Cleveland, National Municipal

American National Biography. Review 5 (April 1916), 226-241.

Newton D. Baker, “Municipal Ownership,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 57 (January 1915).

Daniel R. Beaver, Newton D. Baker and the American War Effort, 1917-1919 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966).

David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, “Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900,” Independent Review 4 (spring 2000): 568, 569.

Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present.

Robert H. Bremner, “Asa S. Bushnell, 1896-1900,” in The Governors of Ohio

(Columbus: The Ohio Historical Society, 1954).

Thomas F. Campbell, Daniel E. Morgan, 1877-1949, The Good Citizen in Politics (Cleveland: The Press of Western Reserve University, 1966).

C. H. Cramer , Newton D. Baker: A Biography (Cleveland: World Publishing Co. , 1961).

Dictionary of Cleveland Biography. Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

Mayo Fesler, “The Progress of Municipal Home Rule in Ohio” National Municipal Review 5 (April 1916), 242-251.

The Governors of Ohio (Columbus: Ohio Historical Society, 1954).

Frederic C. Howe, The Confessions of a Reformer (New York: Charles Scribner’s

Sons, 1925).

John McF. Howie, “The Master Hand and Mind of Newton D. Baker,” North American Review 204 (August 1916).

A.J. Liebling, The Telephone Booth Indian (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1942).

“Newton D. Baker, Dreamer,” The Plain Dealer, Oct. 30, 1911.

“Ohio Democratic Platform, 1912,” Ohio Almanac and Hand-Book of Information (1914).

Frederick Palmer, Newton D. Baker, America at War (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1931).

Elliott A. Rosen, “Baker on the Fifth Ballot? The Democratic Alternative: 1932,” Ohio History 75 (autumn 1965).

Archer H. Shaw, “New War secretary as his neighbors know him,” The New York Times (March 12, 1916).

Lincoln Steffens, The Struggle for Self-Government, Being an Attempt to Trace American Political Corruption to Its Sources in Six States in the United States, with a Dedication to the Czar (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1906)

Thomas Suddes, “The Adult Education Tradition in Greater Cleveland,” teachingcleveland. org

Willis Thornton, Newton D. Baker and His Books (Cleveland, The Press of Western Reserve University, 1954).

Oswald Garrison Villard, “Presidential Possibilities VII: New D. Baker, Just Another Politician,” The Nation (April 13, 1932).

Hoyt Landon Warner, The Life of Mr. Justice Clarke: A Testament to the Power of Liberal Dissent in America (Cleveland: Western Reserve University Press, 1959).

Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press for the Ohio Historical Society, 1964).

“What the issue is,” The Cleveland Press, Nov. 1, 1913.

“Where Are the Pre-War Radicals?” The Survey 55 (Feb. 1, 1926).

Carl Wittke, “Mr. Justice Clarke – A Supreme Court Judge in Retirement,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 36 (June 1949).