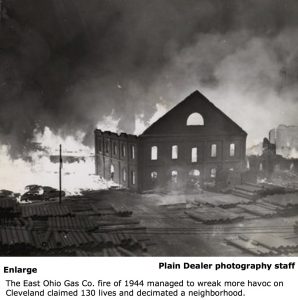

Courtesy of the Plain Dealer. Published October 18, 2004

East Ohio Gas explosions — 60 years later

Edward Krivacic will go to Mass next Sunday because it’s time to remember.

Time to remember the day his neighborhood exploded. Time to remember his dead mother wearing her apron, and his infant niece. And his home destroyed on East 61st Street.

Others will also remember one of the worst disasters in Cleveland’s history: Oct. 20, 1944, the explosions and fire at the East Ohio Gas Co. plant.

Steve Mraz recalls the miracle of his mother’s wedding dress. Anne Strazar, who thought Cleveland was being bombed by the Germans. And Louis Turi, still haunted by parts of a body on a chain-link fence.

It happened 60 years ago, on a bright fall afternoon.

The death toll was 131 people, including 55 employees of East Ohio. Some of the victims were so badly burned they would never be identified.

The first explosion rocked the neighborhood about 2:40 p.m., a Friday.

Krivacic, who had just turned 14, was at Willson Junior High. He did not have to hear the blast. He saw it through the window of his science class.

“It was facing the lake, which was where the fire was,” he recalled. “The teacher thought it was the corner gas station that blew up because it looked that close. But it was probably a mile away.”

“We got released at 10 to 3. I started running down 55th toward my home when I ran across my brother-in-law at 55th and St. Clair. That’s as far as they let us go. They [the fire department] had it blocked off.

“We went down St. Clair and saw everything,” he said. “We saw the manhole covers blowing up, the fire truck blowing up at Norwood and St. Clair.”

The memories of that day are still vivid for the Rev. Victor Cimperman, a Catholic priest who wants to forget.

“I don’t want to remember what I saw,” he said, gazing north from the St. Vitus Village house where he now lives in the old neighborhood. “But none of us can ever forget.”

He can’t forget the devastated wasteland that was his neighborhood. Or the crying children. And frightened adults wandering the streets, looking for relatives, or pieces of their homes.

His sister can’t forget, either.

Anne Strazar, then 18, was working at the nearby Fisher Auto Body when she looked out her window at the “giant silver balls” that housed liquid natural gas at the plant, known as No. 2 works.

“I looked at them all the time, wondered what would happen if they exploded,” she said. “Then, that day, they did. The top blew sky high. There were three or four men on the tank when it exploded. It was horrendous. I thought that the Germans were bombing us, and ran to get away.”

She and her fellow workers ran outside behind the plant to escape, but were blocked by a tall chain-link fence.

“We dropped to our knees and dug in the dirt until we could get under the fence,” she said. “One of my friends died there, she was unable to get under the fence. There were orange and red fireballs everywhere as we ran along the railroad tracks to 71st Street.

It was days before the young woman would be reunited with her family.

The explosion at the plant north of St. Clair Avenue sent a 3,000-degree fireball into the sky, burning, sometimes vaporizing, a square mile of Cleveland’s mostly Slovenian neighborhood. The area looked like Dresden or London after a World War II bombing raid.

Like Anne Strazar, many people thought the explosion was the work of German bombers, or saboteurs.

The disaster was something the neighborhood had always feared.

“People looked at those big gas storage tanks and worried that they would explode someday,” said Father Cimperman, who grew up in the neighborhood. “The gas company always said it could never happen, that the tanks were perfectly safe.”

Cleveland in 1944 was a very different city. Employment was booming, buoyed by war demands for tanks, planes and ammunition.

Fuel for those factories came in the form of liquid gas supplied by East Ohio. Years before, scientists had determined that 600 times more gas could be stored if it was liquefied at minus 250 degrees. At No. 2 works, there were four tanks – three globular and one cylindrical – holding millions of gallons of liquid natural gas.

On the afternoon of Oct. 20, a thin wisp of vapor was seen leaking from beneath the cylindrical tank – No. 4. The vapor wafted to East 61st Street. Somehow, the vapor was ignited by a spark. The exact cause was never determined.

Houses on both sides of East 61st and 62nd streets burst into flames. People in other parts of the city thought the entire East Side was burning. Birds were flash-fried in flight. Houses a half-mile away were blistered by the heat.

The force of the explosion blew out storefronts a mile away and caused the bells to chime at St. Vitus Church on Glass Avenue.

At 3 p.m., intense heat melted supports on the ball-shaped tank next to No. 4. It collapsed and exploded. The ball of flame could be seen at John Adams High School, seven miles away.

Freed from the tanks, liquid gas ran down the streets and disappeared into sewer openings. The gas seeped into basements. Homes exploded. Manhole covers were blown hundreds of feet into the air.

Father Cimperman shudders at what would have happened if the blast occurred a half-hour later.

“Think about it,” he said. “All the children would have been at home or walking home when it happened. They would have been killed along with everyone else if it had happened just a little later.”

Turned away by firefighters, Ed Krivacic, whose father had died of cancer the previous February, went to the home of his sister and brother-in-law in Euclid. His school was used by the Red Cross to house 680 people left homeless by the blast.

Three days later he was able to get back to the neighborhood. His mother’s body was found later that day in the

ruins of a neighbor’s house. “They found her, my mom, on top of my niece,” he said.

Krivacic was not there then. But he did see searchers “dig up four siblings [from the neighbor’s family]. They were all charcoal wood.”

Frank Likovic, a brother-in-law, identified Krivacic’s mother. Likovic had been with her before the fire and recognized the apron she had been wearing.

Krivacic thinks his mother went next door because it was a bigger house and she thought it might be safer.

“But even if she’d stayed home, it would have been the same,” he said. “All the nearby houses were destroyed. If she would have gone out the back to 55th, she probably would have survived.”

Behind four of the incinerated houses was a company called Knock Fire Brick, with stacks of bricks in the open air. The bricks survived.

The Cuyahoga County morgue was besieged by people desperate to know if their relatives or loved ones were among the dead.

Identification took a long time, for many because bodies were charred beyond recognition. Identification was made by clothing, dental work and jewelry.

Sixty-one victims, including 21 never identified, are buried around a monument at the Highland Park Cemetery on Chagrin Boulevard.

Steve Mraz survived.

He was 6, and remembers heading back to the upstairs apartment his family rented in a house at East 61st Street and Carry Avenue. The home was gone.

On Oct. 20, his mother, Ann, had just returned from the grocery store when the first blast went off. She grabbed her son.

“I just got home from the hospital,” recalled Mraz, 66, of Auburn Township. “I had pneumonia. She grabbed me and ran down the stairs. She had lost her slippers and had the choice of running through fire or glass. She chose glass and never got cut. She hailed a cab, and went to my aunt’s, her sister’s, on East 40th across from St. Paul’s.”

His most dramatic memory would come after the fire, “what we call the miracle deal,” he said.

“The entire house was gone except the chimney,” he said. “My dad got a pass to go through the police line the next day, and there at the base of the chimney were my dad’s tamburitza [an instrument similar to a mandolin] and my mother’s wedding dress.”

The dress did not have a scorch mark on it, and his mom, now 86, still has it. And the tamburitza? “I still play it,” he said. Others lost everything.

People cried over tin boxes that held charred remains of their life’s savings. After the Depression, many people kept their money in tin cans. These were incinerated.

Despondent survivors were told the federal government

would only refund bills that were at least 3/5 intact. Anything less than that was subject to a determination by the Treasury Department.

Louis Turi, 81, of Wickliffe, thought he wouldn’t get to see any action in World War II, but he saw plenty in 1944 – without ever leaving Cleveland.

Turi, then 21, was a member of what is now called the Ohio Military Reserve, which backstops the Ohio National Guard during emergencies. He joined the unit after being deferred from World War II.

Turi, now a lawyer, was a college student working at Graphite Bronze Co. on St. Clair Avenue when East Ohio blew up.

“I got the call and dropped everything. I told people I didn’t know when I was going to be back,” Turi said. “We were there four days. They evacuated the entire area from 55th east to 65th or 67th, to just south of where Sterle’s [restaurant] is on East 55th.”

Two sights haunt him still.

“On a fence there were the remains of a human body, a chain-link fence. Somebody tried climbing it [to escape the fire].” he said. The other was a 1935 or ’36 Plymouth that the initial explosion pitched into a lamp pole, slightly folding the heavy vehicle around the pole.

“The whole thing looked like a war zone.”

Neil Durbin, a spokesman for Dominion East Ohio, said the gas company’s most significant safety measure after the tragedy was when they “shifted from liquefied natural gas to a system of underground natural-gas storage.”

Durbin said the technology was developed in the 1940s, and allowed them to convert depleted gas wells into natural-gas storage facilities by pumping the gas into the old wells.

“We currently operate the largest underground storage in North America, much of it in this area.” He said a lot of the gas is stored near Belden Village mall in North Canton.

Cleveland City Councilman Joseph Cimperman, nephew of Father Cimperman and Anne Strazar, said he respects East Ohio Gas for staying in his district and helping to heal the community.

East Ohio Gas paid more than $3 million in damage settlements to the neighborhood and $500,000 more to families of the dead gas company employees. Houses were replaced, new families moved in and the life of the neighborhood continued.

The gas company remains part of the neighborhood. The former location of the tanks is now Grdina Park.

— This article was originally published in The Plain Dealer on Oct. 18th, 2004. It was written by Michael Sangiacomo and James Ewinger.