by Grant Segall May 8, 2025

One hundred years ago, a pioneering librarian opened a new flagship for the pioneering Cleveland Public Library.

The link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

by Grant Segall May 8, 2025

One hundred years ago, a pioneering librarian opened a new flagship for the pioneering Cleveland Public Library.

The link is here

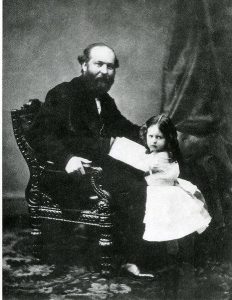

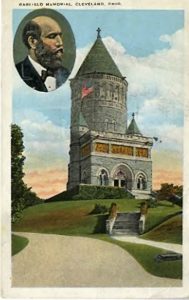

1) James A. Garfield at 16, 2) James A. Garfield with daughter Mollie in 1870, 3) Postcard of Garfield Monument at Lakeview Cemetary (All photos: Cleveland State Special Collections)

The Western Reserve’s Self-Made President

By Grant Segall

A delusional job-seeker and a backwards doctor ended one of Northeast Ohio’s most promising stories too soon.

James Abram Garfield was just 49 years old and not quite four months into the presidency when slain in 1881 by Charles J. Guiteau, a spurned supplicant trying to boost Garfield’s foes. It took Doctor (his real first name) Willard Bliss 79 more days to finish off the patient. Now we’ll never know what might have been accomplished by the second youngest president to that date and still the only one from the Western Reserve (the hopeful Mark Hanna, Newton D. Baker, Dick Celeste and Dennis Kucinich notwithstanding).

The self-made Garfield showed rare potential. He was the last person to rise from a log cabin to the White House. He’s still the only one to have gone there directly from the House of Representatives, although he was also a senator-elect at the time. During his swift career, he went from janitor to president of the future Hiram College, then to major general, House minority leader, long-shot presidential nominee and innovative front-porch campaigner. He never lost an election, even at college. A self-taught lawyer, he argued his first case in the nation’s highest court and won an important precedent. A polymath, he created a proof of the Pythagorean theorem that a journal published. He was such an exemplary Horatio Alger hero that Alger wrote his campaign biography.

But he also had plenty of flaws. He entered into conflicts of interest. He undercut a few superiors, sometimes while ostensibly supporting them. He joined a dubious partisan vote in 1876 that gave the White House to Rutherford “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes. He jilted a sweetheart and apparently cheated at least once on his wife. He zigzagged on some leading issues, including tariffs, Reconstruction, and civil service. He tried variously to appease and defy party bosses.

“Garfield,” former President U.S. Grant once wrote, “is not possessed of the backbone of an angleworm.”

Grant’s subject could be moody, touchy and self-righteous. He fumed in his diary about enemies: “barking hounds” with “vulture eyes” who launched “bitter and malignant assaults.” He sounded suspiciously innocent at times, as in “I am a poor hater” and “I am conscious of not being fitted for the partisan work of politics….” He could stretch the truth, as in “I have never asked anybody for a place.”

After he died, the nation memorialized him widely and moved on. In 1935, Novelist Thomas Wolfe called him one of the “lost presidents” of the late 1800s, already blurred by time. Garfield may have shaped his country more in death than life. His assassination clinched the case for civil service reforms and his mistreatment for medical ones.

His log cabin is gone, and his native Orange Township, too, but a replica cabin stands in what’s now Moreland Hills. The youngest of four surviving children, he was born on Nov. 19, 1831, and named James for a dead brother. His strong-willed mother, Eliza, later recalled that her biggest baby looked like a “red Irishman.”

Before James turned 2, his father died after bad medical care foreshadowing his son’s. Eliza said that the child learned to read at 3 at a local school and often escaped chores through books. When he was 10, she remarried. A year later, she fled with the children, shocking neighbors, provoking a divorce.

Garfield grew to a then-impressive 6 feet tall. He was sandy-haired, blue-eyed, and vigorous but clumsy. At 16, he left home despite Eliza’s pleas. He worked the Ohio and Erie Canal for six weeks and fell overboard 14 times. Not knowing how to swim, he had to be fished out. He came home sick and determined to work with his mind. He attended Geauga Academy in Chester Township and taught at a nearby school meanwhile.

Near age 20, he entered the fledgling Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, run by his childhood denomination, the Disciples of Christ. (The school would later be renamed Hiram College for its town.) Garfield worked his way through as a janitor, carpenter, teacher, and ordained minister, speaking and preaching eloquently around the area for faith, abolition, and more. “I love agitation and investigation and glory in defending unpopular truth against popular error.” he wrote in a letter.

He studied deeply and widely but also played: hunting, fishing, shooting billiards, drinking a little, and passing time with the ladies. He courted a woman and backed off rather late by the era’s standards. Then he spent several years courting the smart, serious Lucretia (Crete) Rudolph, a Hiram trustee’s daughter. The two declared their love but set no wedding date. “There is no delirium of passion nor overwhelming power of feeling that draws me to her irresistibly,” he told his diary. “I feel inclined to be cautious.”

At age 22, Garfield left his sweetheart behind and entered Williams College in Massachusetts. Charming his young Eastern classmates, he led a literary club and journal, crusaded against fraternities, joined the new Republican Party, and became class salutatorian.

He returned to the Eclectic and taught many subjects. He sheltered a runaway slave and tried to rescue two captured slaves, but the latter proved to be pranksters in blackface. After a year back at the school, he helped the faculty oust the president and won the helm over an older rival.

In 1858, he finally married Crete. They had seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood. The next year, while refusing to campaign, he let the party nominate him on the fourth ballot for state senator and secure his easy election in a Republican district. At age 28, Columbus’s youngest senator quickly became a leading speaker and draftsman. Trying to reconcile the North and the South, he spoke in Louisville and brought Kentucky and Tennessee lawmakers to Ohio. He also wrote reports on weights and measures, education, and geology, calling vainly for a state geological survey. Meanwhile, he studied law on his own and passed the bar exam.

During the Civil War, Garfield organized a regiment, beat greater forces in Kentucky, and galloped through fire at Chickamauga. He became chief of staff to Gen. William Rosencrans, who wrote that the aide was “ever active, prudent and sagacious… He possesses the energy and the instinct of a great commander.” But Garfield criticized his superior’s dilatory warfare in a letter to a higher-up that later leaked and drew blame for Rosecrans’ demotion.

At home, Garfield was a kind, playful father. But, during his war wanderings, he seems to have had at least one affair, according to biographer Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University. Garfield later wrote to Crete that “by your grand faith and truth and endurance, our love was saved and purified through the fiery ordeal of the years.”

While off at war, he was elected to the House of Representatives. He took his seat in late 1863 and served 17 years. He chaired committees on banking and appropriations, the Census, and military affairs. He strengthened the wartime draft. He helped to start the U.S. Geological Survey, doing for the nation what he’d failed to do for Ohio. He spurred what would become the Education Department. He supported “hard money” backed by gold. He opposed unions and wanted troops to break strikes. He opposed most federal relief and called cooperative farms “communism in disguise.” He docked the wages of his political appointees to print a campaign speech supporting civil service reform.

Outside the Capitol, Garfield joined the boards of the Smithsonian Institution, the historically black Hampton Institute, and his former schools, Hiram and Williams. After Lincoln’s slaying, the Congressman reportedly calmed a vengeful mob in New York City, declaring, “God reigns, and the government at Washington still lives.” He also practiced a little law. In “ex parte Milligan” of 1866, he defended Southern sympathizers in the U.S. Supreme Court on charges of treason and won lasting limits on the jurisdiction of military courts.

The early 1870s brought controversies. Garfield took $5,000 to help a company win a contract to pave D.C. streets. Also, despite his initial denial, he apparently held shares or options awhile in Credit Mobilier, linked to the federally funded transcontinental railroad, and made or borrowed some $300 from the company. He was denounced on the campaign trail but survived.

In 1869, Garfield built a brick home in D.C. In 1876, keeping up with gerrymandered borders, he bought a grassy farm on Euclid Avenue in Mentor that reporters would punningly call Lawnfield. Soon he added that handy front porch.

Also in 1876, Garfield became Republican minority leader. That year’s presidential election foreshadowed 2000’s. Hayes lost the popular vote, but a commission including Garfield voted along party lines to give him pivotal Southern electoral votes, including Florida’s. Garfield fought for some of the president’s goals and opposed others, including a ban on political campaigning for civil servants.

In 1880, U.S. Treasury Secretary John Sherman of Ohio endorsed Garfield for the federal Senate, effective the next year. State lawmakers, who chose senators back then, complied. In turn, Garfield promised to nominate Sherman for president.

With Hayes not seeking a second term, the leading Republican candidates were Maine’s strong-willed Congressman James G. Blaine of the so-called Half-Breed faction and former president U.S. Grant of the Stalwarts, led by New York’s domineering senators, the body-building, philandering Roscoe Conkling and his protege, the slight, philandering Thomas Platt. Politicians and reporters began calling Garfield a dark horse who might unite the party at its May convention in Chicago.

Garfield chaired the convention’s rules committee and thwarted a Stalwart demand for each state to vote as a bloc. Then he nominated Sherman with more praise for unity than for the candidate. On each ballot from the second through the 28th, Garfield got one or two votes. On the second day and the 34th ballot, he got 17. He objected to the votes but was overruled. He won handily on the 36th ballot, still the latest one in Republican history, and gave in.

His first challenge was to placate the Stalwarts, whose support was crucial, especially in New York. He picked a minion of theirs as a running mate: Chester A. Arthur, whom Hayes had dumped as customs collector of Manhattan’s port for doling out too many patronage jobs. In Garfield’s acceptance letter, he promised to consult local leaders about local appointments. Then he made a pilgrimage to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York to assuage Republican leaders there. Conkling checked in but skipped out before the meeting, perhaps to hide his hand in any deal. Afterwards, Garfield wrote in his diary “No serious mistake had been made and probably much good had been done. No trades, no shackles, and as well fitted for defeat or victory than ever.” Conkling resurfaced, claimed that Garfield had kowtowed, and condescended to stump for the ticket.

Back at Lawnfield, Garfield created the front-porch campaign, later perfected by William McKinley in Canton and Warren Harding in Marion. He spoke in English and German to more than 17,000 choreographed visitors, from President Grant to the Jubilee Singers of the historically black Fisk University. On view, he worked the farm and played horse with his sons. With a telegraph and two secretaries, he oversaw the campaign nationwide.

Supporters of the Democratic nominee, General Winfield Scott Hancock of New York, resurrected some controversies and invented others, including a forged letter in which Garfield supposedly called for unrestricted Chinese immigration. In the end, Garfield won by less than 0.1 percent of the popular vote but with a more comfortable 214 of 369 electoral votes, including New York’s.

Between victory and assassination, Garfield’s toughest challenges were appointments. He chose “Ben Hur” novelist Lew Wallace for ambassador to Turkey and poet James Russell Lowell for London. He outraged the Stalwarts by picking Blaine as secretary of state. He tried vainly to mollify them with Isaac MacVeagh from a Pennsylvania Stalwart family as attorney general and New York Postmaster Thomas James as postmaster general. At his hotel the night before the inauguration, Garfield was hastily revising his address when Conkling stormed into the room with Platt and Arthur to blast the proposed cabinet. Garfield listened in near silence.

For months, the president remained trapped between the Stalwarts, the meddlesome Blaine and the Democrats. Nominations were withdrawn, resignations threatened, maneuvers executed, and a filibuster thwarted. Garfield gave Arthur’s old port job to Judge Wililam Robertson, a leading Half-Breed. An outraged vice president gave his boss the silent treatment for a month but said plenty to the New York Herald, such as, “Garfield has not been square, nor honorable, nor truthful.” The president barred him from the White House for a while.

In other matters, Garfield supported a probe by the surprisingly independent-minded James and MacVeagh of postal graft by Republicans, including Garfield’s campaign manager. He refinanced war debts from 6 percent interest to 3.5 percent, saving more than $10 million per year, or more than 3 percent of the federal budget. He signed the Treaty of Washington, which called for arbitration of Civil War damage claims against Britain and renewed fishing agreements with Canada. He and Blaine offered to mediate disputes between other countries in our hemisphere. They also planned a Pan-American conference that President Arthur would scrap.

The Stalwarts finally imploded. Conkling and Platt quit the Senate to protest Garfield’s appointments. They presumed re-election in Albany, but the Half-Breeds promptly caught Platt in bed with a woman not his wife, and the legislature turned elsewhere.

Garfield’s domestic life was more respectable. His mother lived at the White House and often rode the stairs in his arms. His wife caught malaria in swampy D.C. and recuperated on the shore in Elberon, N.J. Crowds kept streaming into a rather open White House in search of jobs. “Some civil service reform will come by necessity,” Garfield told his diary, “after the wearisome years of wasted Presidents have paved the way for it.”

No one was more wearisome than Guiteau, a self-taught lawyer, like Garfield, and a dropout from a polygamous commune. Guiteau hounded the White House, the State Department, even Garfield’s church, ranting during a service. He was often turned away but never arrested. He began to tote a pistol but balked twice at shooting the president. On July 2, he tracked Garfield to the Baltimore and Potomac depot. The president planned to join Crete, drop off two sons at Williams, get an honorary degree there, and summer at Lawnfield. This time, Guiteau found the nerve to fire.

“My God!” cried Garfield, lurching. “What is this?”

Guiteau fired again. “I am a Stalwart,” he declared, “and Arthur will be president.” One bullet grazed the victim’s arm. The other lodged in a vertebrae.

Doctor Bliss was summoned, and Garfield was carted back to the White House. Spurning a recent trend for antiseptic care, Bliss and chosen associates repeatedly probed Garfield’s wounds with unwashed hands and tools. Alexander Graham Bell brought an invention to find the hidden bullet but failed. For weeks, the patient was feverish, nauseous and underfed, losing some 100 pounds. The doctors barred him to most of his colleagues, and the administration largely idled.

Garfield finally insisted on a trip to the Jersey shore. He died there on Sept. 19. A train draped in black took his body to Cleveland’s Public Square. There 150,000 people, about equal to the city’s population, paid their respects.

On trial, Guiteau blamed Garfield’s death on the doctors. He was convicted and hung, but medical experts agree with him today. He fulfilled his goal with Arthur’s reign. But the ascendant, tainted by a killer’s support and secretly dying from a kidney disease, promoted the Pendleton Act of 1883, which created civil service jobs, tests and protections.

Meanwhile, friends raised funds to support Garfield’s survivors, build the Garfield Monument at Lake View Cemetery, turn Lawnfield into a shrine, and create the first presidential memorial library there. Crete finished raising impressive children, including a Williams president and a U.S interior secretary. She died near the then-impressive age of 86.

In the “American Presidents” series, Ira Rutkow gives Garfield tepid reviews: “Garfield was not a natural leader and did not dominate men or events…”

In “Garfield,” Allan Peskin of Cleveland State University says that the Mentor man’s “stormy presidency was brief and, in some respects, unfortunate, but he did leave the office stronger than he found it.” He also says Garfield and Blaine “forged the Republican Party into the instrument that would lead the United States into the twentieth century.”

Kenneth D. Ackerman, author of “Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield,” told The Plain Dealer in 2006 that Garfield grew during his short reign. “He could have become a much stronger, much more effective president if he’d had the chance. Unfortunately, we’ll never know.”

For further reading:

“Garfield,” Allan Peskin, Kent State University, 1978, 1999.

“Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield,” Kenneth D. Ackerman, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003.

Places to visit:

The Garfield Monument, open daily, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., April 1 to November 19, Lakeview Cemetery, 12316 Euclid Ave., Cleveland (or enter at Mayfield and Kenilworth Roads, Cleveland Heights), 216-421-2665, lakeviewcemetery.com.

Garfield’s replica childhood cabin, open 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturdays, Moreland Hills village campus, 4350 SOM Center Rd. Photos and memorabilia are also displayed at the hall, open 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays. See morelandhills.com/moreland-hills-historical-society/the-james-a-garfield-memorial-cabin.

About the Author

Grant Segall has spent 39 years on daily newspapers, including 30 at The Plain Dealer. He currently writes the My Cleveland column and covers the Berea school district for the PD and Sun News. He has shared in three national prizes and won several state and regional ones.

Segall has freelanced for Time, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil has been published by Oxford University Press and by houses in Korea and China. His short stories have been published in college journals, including Whiskey Island at Cleveland State, and in independent zines. He lives in Shaker Heights and has three sons.