They Also Ran: The Women Who Would Be Mayor, 1961 to 1997

by Marian Morton

They were from different political parties, of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, and ran for mayor of Cleveland for different reasons. But they shared a common fate: they lost their elections. None was even close. But being elected mayor of Cleveland isn’t the only way to measure political importance. All four women served their communities and their parties for decades, challenged the political status quo, and redefined what it meant to be a woman in Cleveland politics. Like the women who went before them, Albina Cermak, Jean Murrell Capers, Mercedes R. Cotner, and Helen K. Smith, blazed the trail for the women who would follow.

Cleveland women first engaged in partisan politics in 1911 when they organized to win the vote. It was tough going. Parades and demonstrations, speeches on soap boxes, and ceaseless lobbying of men in power led only to failed campaigns in 1912 and 1914 to amend the Ohio constitution to enfranchise women. In 1917, a woman suffrage amendment to the Ohio constitution was rejected by voters. Finally, in 1920, the Nineteenth (Woman Suffrage) Amendment was ratified by Congress and the states, and adult American women became voters.

Trained and inspired by the suffrage movement, women in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County immediately seized the opportunity to run for political office. Two were elected to the Ohio legislature in 1922. Nettie McKenzie Clapp, a Republican, served three successive terms in the Ohio House of Representatives. Maude Comstock Waitt, also a Republican and a member of Lakewood City Council, was elected four times to the Ohio Senate. Mary B. Grossman, an active suffragist, a founder of the Women’s City Club, and a member of the League of Women Voters, lost her first bid for a municipal judgeship. In 1923, however, she won a place on the bench that she occupied until her retirement at age 80 in 1957. The most prominent of this first generation of women to run for office was Florence E. Allen. A stump speaker and debater for suffrage, Allen had successfully defended before the Ohio Supreme Court the right of East Cleveland women to vote in municipal elections. In 1920, she was elected to the Common Pleas court, the first woman in the United States to be elected to a judgeship. In 1922, she became the first woman to be elected to the Ohio Supreme Court; in 1934, the first to be appointed to a federal court, the U.S. 6th Sixth Circuit, and in 1958, the first woman to become a chief judge of any federal court, the U.S. 6th Circuit.

Cleveland women also ran for Cleveland City Council. Two – Anna Herbruck and Isabella Alexander – declared their candidacies for Council on August 20, 1920, the day that the Nineteenth Amendment passed. “Millinery in Ring for Council Race,” commented the Cleveland Plain Dealer.[1] Both women apparently thought better of their bold actions and withdrew.

In 1923, however, Clevelanders elected the first two women to City Council. Marie Remington Wing, a suffrage activist and lawyer, had worked for the YWCA and then for the Consumers’ League of Ohio, an organization dedicated to improving the working conditions of women and children. She ran as an independent. While on Council, Wing worked to establish a Women’s Bureau in the Cleveland Police Department. She lost her Council seat in 1927, but in 1933, she was appointed to the Cuyahoga County Relief Commission. From 1937 to 1953, she served as attorney to the regional Social Security Board. Helen H. Green was also elected to Council in 1923. Green, an endorsed Republican, was president of the county Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which for decades had launched women into public life. During Green’s first term, she expressed some dismay with her colleagues on Council: “The best trained man will not follow a woman, even to victory,” but defended them as “gentlemen, not highwaymen.” [2] During Green’s second term, she supported regulating industries “which give off fumes or liquid wastes considered dangerous to health,” an early effort to preserve the environment that outraged the Chamber of Commerce and other spokesmen for industry. [3] She also defended the job and salary of the woman who headed the city’s park department: “Mrs. Green Pleads for Equality,”read the headline. [4] Both women lost re-election bids in 1927. In its tribute to them, the Cleveland Plain Dealer emphasized their gender: “In Mrs. Green, the Council loses one of its two grandmothers [the other was Mildred Bronstrup, appointed to her husband’s seat after his death], its foremost dry, and one of its most assiduous workers …. In Miss Wing, the only woman attorney on Council will step out.” [5]

Thirty-seven women followed these pioneers onto Council. The longest-serving was Margaret McCaffery. First elected in 1948 to her late husband’s seat, she served her East Side ward until 1964 when she lost her seat to redistricting. Nothing daunted, she ran successfully two years later from the West Side, an unprecedented political crossing of the Cuyahoga River. When she resigned in 1973, she had been on Council a total of 24 years. McCaffery recalled that initially she battled the notion that a woman’s place was in the home, not in Council, but that male colleagues gradually came around and “started wearing ties and quit swearing.” In 1956, there were six women on Council, more than ever before, or since; they included McCaffery, Jean Murrell Capers, and Mercedes R. Cotner. The Councilwomen met in mini-caucuses – the men called them “hen parties” – to discuss the interests peculiarly appropriate to their gender, especially “good housekeeping and public safety,” McCaffery remembered. Three of the women served on Council’s committee on public welfare, chaired by McCaffery, which dealt with public health, charities, direct and work relief. (Capers was vice-chair.) Despite the difficulties she had experienced, McCaffery urged other women to get into politics: “politics needs women with understanding and compassion.”[6]

Albina Cermak

Albina Cermak (1904-1978), the first woman to run for mayor, followed in her parents’ political footsteps. Her father was a precinct committeeman. Her mother was a suffragist. Cermak’s pioneer candidacy in 1961 reflected her mother’s passion for equal political opportunities for women.

Cermak dropped out of nursing school to become the book-keeper for her father’s dry goods store, then went to work for the city’s public utilities department, where she became a supervisor. At age 21, she began her ascent up the political ladder, serving as Republican precinct committeewoman, vice chairman and secretary of the county Republican Central and Executive Committees, and chairman of the Republican Women’s Organization of Cuyahoga County. She was also a member of the county Board of Elections and a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1940, 1944, and 1952. In 1953, with the support of two Republican congressmen – U.S. Senator George Bender and U.S. Representative Frances P. Bolton -, Cermak was appointed U.S. Customs Collector for Cleveland by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. [7] (Bolton served the 22d Congressional District from 1940, when she succeeded her late husband, Chester C. Bolton, until 1968.)

In 1957, Cermak was elected president of the Catholic Federation of Women’s Clubs, and women’s organizations became her earliest supporters. (All news about Cermak, until she ran for mayor, appeared in the women’s section of the newspaper, alongside tips on hair styles and hats.) In 1961, Cermak’s customs appointment was threatened when Democrat John F. Kennedy became President. A speaker on the status of women at the Women’s City Club pointed to Cermak’s appointment as a “great gain” for women and complained, “Now there is no woman on the election board and the women in either party don’t seem to give a darn. This would not have been true 30 years ago. We are not only not making gains; we are losing ground.” [8]

In 1961, the Republicans’ first two choices, both male, declined to run for mayor against the popular Democrat Anthony Celebrezze, then completing his fourth term. Cermak got the nod. She ran unopposed in the Republican primary.

Anne Celebrezze, when asked how she felt about her husband running against Cermak, reportedly replied, “May the best man win.” [9] Cermak was well aware of her path-breaking role: “I hope nobody will vote for or against me because I am a woman.” [10] Her underdog status was enhanced by being a Republican in a Democratic town.

Although she had never run for city-wide public office, Cermak was an energetic, enthusiastic campaigner. She took the offensive immediately. Denied a permit to kick off her campaign on Public Square in front of the statue of Tom L. Johnson, Cermak accused the Celebrezze administration of denying her right to free speech. [11] She listed as her key issues air pollution, the need for new industry (“We’ve slipped. People are out of work because industry has moved”), saving the lake front (“It makes me mad when a mother has to rub her children down with alcohol after they’ve gone into the dirty lake”), slum clearance (“City Hall has certainly been dragging its feet in this regard”), and better public transportation (“When you have to wait 25 minutes for a bus, it’s ridiculous”). In good Republican fashion, she opposed a city income tax and accused the administration of wasting tax-payers’ dollars. [12]

In most unladylike fashion, she described Celebrezze’s as “an administration of political do-nothings unmatched in the city’s history. It takes arrogance for the mayor to run again on old promises that have not been carried out. ” [13] She challenged Celebrezze to pledge that if elected, he would serve out his term. She thought he was using the mayor’s office as a stepping stone for a run for higher office, probably governor. He didn’t take the pledge, and she was half right. In 1962, Celebrezze left Cleveland to become U.S. Secretary of Health Education and Welfare.

Her broad grin and trademark hat became familiar to voters. On the eve of the election, she and Celebrezze were lampooned at the Press Club’s Pan Lunch in a skit entitled “Anthony and Cleobina.” She laughed uproariously; Celebrezze managed a wan smile. [14]

No-one expected her to win, and she didn’t. Celebrezze won almost 75 percent of the vote, all precincts, and an unprecedented fifth term. Cermak ran unsuccessfully for state senator in 1962 and for clerk of Cleveland municipal court in 1963. For her loyal service to the Republican Party, however, she was appointed the first woman bailiff to the Common Pleas Court in 1964 and to a number of state positions subsequently. Plain Dealercolumnist Elizabeth Kardos, writing in the women’s section of the paper, commented on the importance of Cermak’s run: “Albina Cermak should be an inspiration to all women because she takes her chances on an equal basis with the men.”[15]

Jean Murrell Capers

Jean Murrell Capers ( 1913- ) met head-on the challenges of being both female and black by maintaining her outspoken political independence. The daughter of teachers, she went to Western Reserve University on a scholarship, one of the university’s few black students at the time. She earned a degree in education and taught briefly before getting her law degree from Cleveland Law School. She passed the Ohio Bar in 1945 and was appointed assistant police prosecutor by Mayor Thomas A. Burke in 1946. “[A]nother first for Negro women,” the Cleveland Call and Post announced proudly. [16]The newspaper later applauded Capers as the one of several “lady lawyers [who] bring beauty [and] brains” to the local legal community. An accompanying photo shows a stylish Capers, smiling mischievously. [17]

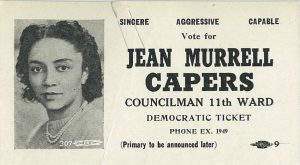

Capers made her first foray into partisan politics in 1943, staging an unsuccessful write-in campaign for City Council. She also ran unsuccessfully for Council in 1945 and 1947. Like Cermak, she early gained the support of organized women’s groups, and in 1949, she got one of her few political endorsements from the Glenara Temple of Elks, of which she was a member. “[I]t is high time that Negro womanhood took its place in the sun of city politics,” said Republican leader and temple member, Lethia C. Fleming. [18] In 1949, on her fourth try, Capers became the first black woman to be elected to City Council and the first Democrat to be elected from what had historically been a Republican ward.

Her four subsequent elections to Council reflected her ability to organize her ward and get out her supporters, doubtless impressed by her education, her political skills, and her glamorous appearance. Capers fought for a swimming pool for her ward’s children and offered a prize for the neighborhood’s cleanest yard.

But she also sparked plenty of controversy and made plenty of enemies. She joined forces with Council member Charles V. Carr in an unsuccessful effort to make the possession (as opposed to the sale) of policy slips legal despite police efforts to crack down on the numbers racket. [19] And despite the opposition from local pastors, she got a license for a local bingo parlor. She criticized Cleveland’s ambitious slum clearance program: “In every instance since urban renewal began, the city has created more problems than it has cured. This is reflected in increased crime and lower sanitation standards.”[20] (Its critics often referred to urban renewal as “Negro removal.”)

Her opponents alleged that she had ties to rackets figures and pointed to her poor attendance record at Council meetings. There were also allegations of voter fraud in her ward in 1952 and 1953. In 1956, she was the only black member of Council to oppose the fluoridation of city water, further estranging her from the Democratic majority. [21]

Even though it had earlier praised her, Capers’ most outspoken critic became the Cleveland Call and Post, the city’s African-American and Republican newspaper, which accused her of being a lazy Councilman and a “wholly irresponsible person.” [22] She was a “vicious, skilled campaigner,” the paper claimed, whose sex “protected her from retaliation in kind.”[23] Her sex did not protect her from savage attacks by the paper – for example, for her opposition to the appointment of Charles P. Lucas, a black, to the Cleveland Transit Board in 1958: “the odor of selfish irresponsibility and putrid demagoguery … marked the conduct of Mrs. Jean Murrell Capers,” the paper spluttered. [24] Everyone wanted her out of office except her constituents.

By 1959, however, although she was chairman of Council’s powerful planning committee, Capers had lost her Council seat to James H. Bell, the candidate endorsed by local Democrats. Bell “ has retired, at least temporarily, one of Cleveland’s most colorful and successful political demagogues …. [who] was possessed of a vibrant sort of feminine attractiveness, an excellent family background, and a razor sharp mind, ” wrote the Call and Post. [25] Capers unsuccessfully filed suit in Common Pleas Court to set aside Bell’s “fraudulent victory.” [26] Undiscouraged, she ran unsuccessfully in 1960 in the Democratic primary for state Senate in a large field that included Carl Stokes, and in 1963, she lost a primary race for her old Council seat.

In 1965, Capers and her League of Non-Partisan Voters organized the movement to draft Stokes to run as an independent mayoral candidate, a race which he lost. Only two years later, however, the league supported Republican Seth Taft when he ran against Stokes for mayor. Capers minced no words when she explained league’s about-face: “Mr. Taft has qualities superior to those of his opponent and has the broad personal knowledge necessary to administer the complex affairs of the city. Stokes knows nothing about anything and is far too superficial in our judgement to serve as mayor. Carl Stokes especially lacks the knowledge and understanding necessary to solve this city’s crisis in human relations.” [27] Capers subsequently acted as the lawyer for Lee-Seville homeowners who fought off Stokes’ plan to locate public housing in their neighborhood. In his embittered autobiography, Stokes called her “one of the brightest politicians ever to come out of Cleveland” but also accused her of being a hustler who supported him in 1965 only to get herself back into politics. [28]

In March 1971, Capers decided to run as an independent in the mayoral primary. She had joined the new National Organization for Women and hoped to win support from the emerging woman’s movement. In mid-summer, she discovered that she had missed the Board of Elections filing date for independents but persuaded a federal judge to overturn this early filing date. The date became a moot point since she did not get enough valid signatures on her petition and was disqualified from the mayoral race. Thanks to a divided Democratic Party, Republican Ralph Perk was elected mayor.

By 1976, Capers had become a Republican herself, and her former nemesis, the Call and Post, endorsed her candidacy for Juvenile Court Judge. She lost this race, but Republican Governor James A. Rhodes appointed her to a municipal judgeship in 1977, a position she held until her retirement in 1986. Reflecting on her long, difficult political career, Capers pointed to her double handicaps of race and gender, maintaining that her “detractors resented her not just because she was a black woman but because she was an educated black woman. ‘They still had the concept that the only place for a Negro woman was on her knees scrubbing the floors. If I had been a dumb Negro woman, I would have gotten along much better.’”[29]

In recognition of her long, difficult political career, Capers earned many professional honors. These include the Norman S. Minor Bar Association Trailblazer Award and induction into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame.

Mercedes R. Cotner

Mercedes R. Cotner (1905-1998) had a long, respected career in Cleveland politics. Although she was often publicly identified as a wife, mother, and grandmother, her gender did not become a political liability until she ran for mayor in 1973.

She grew up in Ohio City. Her father, John S. Trapp, was a jeweler. She learned stenography and bookkeeping at St. Mary Commercial High School; her first job was at Harrington Electric.

Cotner began her political career at the grassroots level as a Democratic precinct committee member and then ward leader. In 1954, she was appointed to fill a vacancy on Cleveland City Council from her West Side ward. In 1955, she won the preferred rating from the Citizens’ League: “Age 50; housewife … [she] has shown an intelligent approach to city and ward problems, if frank and forthright; deserves election on her record.” [30] It was the first of many endorsements. She won that election to Council and four more.

She joined the group of five women on Council that included McCaffery and Capers. They were occasionally asked to address “women’s issues.” In 1958, for example: “Would Women Be Better Leaders Than Men.” Cotner answered diplomatically: “If women were in control, things might be different, but of course, I think that we must have the thinking of both men and women to achieve a complete, well-rounded approach.” (Capers agreed.)[31] In 1960, when someone noticed that there were more women than men of voting age, Cotner, and other women in political office, were asked to comment on women’s roles in politics. “Where would the men be without us?” she asked. “Virtually all the booth workers, precinct committeemen, and those who hand out literature on election day are women.” (McCaffery agreed.)[32] It apparently didn’t occur to Cotner that a woman would run for mayor because Cermak hadn’t yet, and Cotner’s own mayoral contest was more than a decade away.

Cotner’s first battle on Council was against the Celebrezze administration’s plan to put an incinerator on Ridge Road in her ward. Her constituents packed City Council chambers in her support. She lost the fight, but must have gotten some satisfaction when the incinerator, just as she had predicted, spewed smoke and dust into her ward: “The worst thing I have ever seen,” she claimed. [33] Except maybe Public Auditorium, which was discovered to be dirty and untidy: “You need a woman to supervise your maintenance, as City Hall has,” she advised Celebrezze. [34]

Cotner was chosen chairman of the urban renewal and planning committee of Council, a visible and powerful position, as the city set out on the most ambitious urban renewal plan in the country. She supported the Erieview project, the plan’s only success, and advocated high density housing for the St. Vincent Charity neighborhood, which turned out to be too expensive to build and too expensive for its intended low-income residents.

In 1960, Cotner led the opposition to a city fair housing law that would have prohibited discrimination in the sale or rental of property. In a heated debate that pitted her against fair housing advocates, Dr. Benjamin Spock and Reverend John Bruere, Cotner maintained “… I don’t believe I’m breaking any moral code when I say I don’t want to take a certain person into my house – regardless of race, color or creed …. I’ve gone into neighborhoods where garbage is lying on the ground. Don’t tell me they can’t buy a garbage can when there are four or five cars in the driveway.” She also claimed that a fair housing law would violate her constitutional rights to sell or rent to whomever she pleased.[35] In 1973, as a candidate for mayor, she disavowed these embarrassing remarks, saying that the times and the law had changed and so had she. (Cleveland City Council did not pass a fair housing law until 1988.)

In 1963, in a Democratic caucus, her vote for James V. Stanton helped to oust Jack P. Russell as Council President, and Cotner was chosen the first woman Clerk of Council, a position she held for 25 years. During that quarter of a century, she became the adviser and ally of Council Presidents Stanton, Anthony J. Garafoli, and George L. Forbes.

Thirteen days before the 1973 mayoral election, Democrat James Carney, slated to run against incumbent Perk, decided to bow out of the race. At the urging of Garafoli and Forbes, Cotner stepped in as a write-in candidate. The men’s publicly stated intent was to run her not as a serious candidate but to “use her” candidacy to point out that the city charter did not allow a last-minute substitution on the ballot.[36] However, when the Eighth District Court of Appeals ruled that her name could appear on the ballot, she got the advantage over the eight other write-in candidates. These included another woman, the Socialist Workers, Party candidate Roberta Scherr, who had run third in the nonpartisan mayoral primary.

Eleven days before the election, Cotner began to campaign in earnest. With little money and even less time, Cotner waged as vigorous a campaign as she could, invading Perk’s territory on the East and Southeast Sides, including ethnic restaurants and clubs. The Democratic Party kicked in only $9,000, mostly for cards and bumper stickers.[37] Although she had been in politics for decades, she was relatively unknown, especially on the East Side : “Mrs. Conter [sic] Gaining in Campaign for Identity,” explained the Cleveland Plain Dealer, misspelling the candidate’s last name.[38] “’A nice elderly lady like you should be home rocking your grandchildren,’” challenged one critic. “’Aw, go on,’” the 68-year-old candidate laughed.[39]

Big-name Democrats, including Governor John Gilligan and U.S. Senate hopeful Howard Metzenbaum, came into town to support her. And despite Cotner’s dubious record on fair housing, so did U.S. Representative Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress: “Mercedes,” she said, “I know what it is like to be a woman. I’ve fought, I’ve struggled. I’ve battled to get where I am.” [40]

Mayor Perk’s wife, Lucille, publicly disapproved of Cotner’s running for mayor, saying it was too big a job for a woman. Cotner accused her husband of doing a mediocre job, mismanaging city funds and shortchanging police and health services: “Anything he can do, I can do better.” [41] Faced with a “charming” opponent who was not only female but older than he, Perk ran “scared but cautious;” he did not attack Cotner but the “discredited Democratic machine” that she was part of. [42] He refused to debate her.

In a record low turnout, Republican Perk beat Democrat Cotner handily by a margin of almost 2-1 in a city in which Democrats outnumbered Republicans 7-1.[43] Gracious in defeat (“these have been the most wonderful 12 days of my life,” she said),[44] she retained her job as Council Clerk. In 1987, her decades of service to the party and her long friendship with Council President Forbes paid off when he appointed her to the Regional Transit Authority Board, a position she held onto when she retired as Clerk in 1989.

As she prepared to step down as Clerk, Plain Dealer columnist Brent Larkin described her as a “force at City Hall,” remarking especially on her close relationship with Forbes. “On the surface, the pair seemed incompatible, but they quickly became inseparable allies. In the early years of Forbes’ presidency, he rarely appeared in public without Cotner at his side. She was his security blanket in a white-dominated society …. Forbes would not be the successful politician he is were it not for Cotner.”[45] A diplomatic way of saying that a black East Side politician needed support from the white West Side. Forbes himself described her as “just like my mother …. [She] kept me from doing crazy things.” (He also recalled with chagrin that when she and he were invited to the Cleveland Club, she was not allowed to sit in the public dining room, which was for men only.)[46]

After her death in 1998, Cotner was remembered as “sweet-spoken and grandmotherly”[47] and eulogized as a “pioneer for women in politics” and “probably the second most powerful person in Cleveland politics during Forbes’ presidency.” [48] She was certainly one of Cleveland’s most loyal Democrats since she did so much for its party leaders and so many of its voters nevertheless abandoned her for Perk.

Both Capers and Cotner were aided by the growing feminist movement, reinforced by federal legislation mandating equal pay for equal work and prohibiting sex discrimination in employment. Cleveland women organized for equality in groups like Cleveland Women Working and the Cleveland Coalition of Labor Union Women. The Cuyahoga County Women’s Political Caucus was founded in 1971 to put more women in elected office. In 1973, nine women ran for seats on Cleveland City Council; four won. One of them, Mary Rose Oakar, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1976. In 1974, women held 12.9 percent of the county’s elective offices; in 1978, 18.3 percent. However, almost 80 percent of these were on school boards and city councils; no women held any of the eleven county offices, and only three were in the state legislature. [49]

During the next two decades, Cleveland women did win high-profile political positions. Mary O. Boyle, after serving in the Ohio House of Representatives, became the first woman to be elected County Commissioner in 1984. Jane Campbell succeeded Boyle in the Ohio House in 1985 and was elected County Commissioner in 1996. In 1991, Stephanie Tubbs Jones was elected Cuyahoga County Prosecutor and went on to the U.S House of Representatives.

Helen K. Smith

Cleveland Councilman Helen K. Smith (1942 – ) built upon these political gains. As a candidate and office-holder, Smith had her critics, but after decades of seeing women in elected office, Cleveland voters, politicians, and media did not say in 1997 – at least, not publicly – that the “best man” should be elected mayor or that the mayor’s job was too big for a woman.

Smith, a Cleveland native with a B.A. from Maryland College of the Sacred Heart and an M.A. from Case Western Reserve University, began her lively political career by leading the unsuccessful 1978 effort to recall fellow Democrat, Mayor Dennis Kucinich. “The recall started at my kitchen table,” she later recalled.[50] (The reference to kitchen tables as the source of homely wisdom is used by both men and women.)

Like Cotner, Smith is white and from the West Side. Like Cotner, she was appointed to a vacant seat on Council – in March 1979 – before winning the seat in her own right in November. She served on Council for 19 years. Her ward, including Ohio City and the Clark-Fulton neighborhood, was racially diverse – white, black, and increasingly Hispanic – and had more than its share of urban ills: unemployment, poverty, high crime rates, housing blight, and social disorganization.

Smith got city-sponsored projects and federal block grant funds for her constituency. She supported tenants at Lakeview Terrace in their contests with the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority management, and with U.S. House Representative Mary Rose Oakar, Smith got federal dollars for the renovation of the public housing project. She insisted on a greater police presence to control prostitution and kept homeless shelters out of her neighborhoods, already saturated with social service agencies. She got credit for a new recreation center, a spruced-up West Side Market, and a new shopping complex across the street from the market, as well as some early gentrification efforts.

Also like Cotner, Smith had a cordial relationship with Council President Forbes, which enhanced her ability to deliver dollars and projects for her ward. In turn, he got crucial support from the West Side. He appointed her Council’s majority leader in 1981 and to the chairmanship of Council’s finance committee. She controlled the distribution of some federal block grant monies, which, according to her critics, went to Forbes’ friends and not to his enemies. She never denied it. [51] Smith also acted as peacemaker after Forbes’ temper tantrums.

She remained on good terms with Republican Mayor George Voinovich, who endorsed her reelection to Council in 1981. When asked in 1985 if she would endorse Democratic mayoral candidate Gary Kucinich over Voinovich, she “laughed for a long time, but never did answer the question.” Almost none of the Democrats on Council answered the question.[52]

In 1988, when Forbes announced that he would not run again for Council, she was mentioned as his possible successor as Council President. In 1989, she endorsed Forbes in his mayoral race against Mike White. When White won, Smith lost her position as majority leader and was not appointed to chair any Council committees.

She became a frequent critic of the White administration. With Councilman Fannie Lewis, Smith was scolded by the Plain Dealer for “infantile” behavior when they criticized Jay Westbrook, White’s choice for Council President. A Plain Dealer cartoonist pictured the conflict this way: a TV interviewer asks a woman, “How do you feel about women in combat?” To which she replies, “That all depends whether you mean in the army or in Cleveland City Council.” [53] A year later, White himself publicly reproved her, ordering her to “cease and desist” her opposition to Westbrook, claiming that even the appearance of Council disunity would harm the city’s bond rating. [54]

In 1994, Smith lost the Democratic primary for the 10th Congressional seat to Frank Gaul despite an endorsement from the Plain Dealer. She also received financial support from Emily’s List, an organization that supports candidates who support women’s rights. In 1996, she faced her old rival, Dennis Kucinich, in that same race. When she withdrew, she won applause from Democratic Party chairman, Jimmy Dimora, for being a team player. Kucinich won the seat, launching his political career on the national stage.

In 1996, she opposed White’s plans to privatize city parking lots and golf courses, and she became – and remained – a vocal opponent of his plans for a new football stadium for a new Cleveland Browns after Art Modell took the old team to Baltimore. “These are dollars that we desperately need in the city of Cleveland for our neighborhoods. I’ve been in this Council the better part of 16 years,” during the Voinovich and White administrations, “and every year the mayor says that [neighborhoods] will be his priority next year. So Gateway was the priority, Society Center was the priority, Tower City was the priority, and now this is the priority.”[55]

In August 1997, Smith entered the mayoral primary against White and four other challengers. The issues that she emphasized in her campaign were often – not always – those considered appropriate for women. For example, her campaign focused on spending money on neighborhoods rather than on downtown projects. She correctly predicted that the new stadium would run over budget: “The Stadium is out of control, and this is the same man [White] that wants to run the Cleveland school system,”[56] a reference to White’s efforts to gain control of the public schools and to what she felt was his domineering political style. Smith believed that voters, not the mayor, should control public education.

Entering the race late and with very little money, Smith nevertheless won 40 percent of the primary vote; White, 55 percent. The remainder was divided among the four other candidates. One of them, Genevieve Mitchell, was the first black female mayoral candidate ever endorsed by the Republican Party of Cuyahoga County; she won 663 votes.

As Smith and White faced off against each other in the November general election, she hammered home her main issues: homes and neighborhoods, not big-ticket downtown projects; schools, not sports stadiums. Her “vision for Cleveland in the new millennium” looked like this: “In our 21st century Cleveland, I walk into Terminal Tower and take the rapid to Kinsman Road…. I … walk into a thriving neighborhood. Men and women … bustle along the street preparing to open up their small businesses. Neighbors gather at a coffee shop to share ideas and news …. Children scurry to a neighborhood school, where teachers and parents work together toward educating, nourishing and training them for the future…. I see a City Hall returned to the role of public servant …. [D]owntown is a neighborhood – one that is shared and nurtured by its residents .… [O]ur neighborhoods boast well-kept, renovated homes. ”[57]

A high point of Smith’s campaign was a City Club debate with White the week before the election. “… Helen Smith came out swinging [in] a performance that surprised many in the audience with its vigor and pointed comebacks.” She attacked White’s claim that crime was on the decrease: “You can’t run a safety department with a revolving door at the top,” a reference to White’s firing three police chiefs. She maintained that White couldn’t possibly run the public school system: “He’s got enough to do at City Hall and he’s not doing it.” Her final words were those she said she had heard from voters all over Cleveland: “Thank you for giving us a choice. And thank you, we need a change.”[58]

White’s threats to privatize city jobs won Smith the endorsement of the AFL-CIO, and his combativeness with the Cleveland Teachers Union won her theirs. She had a few stalwart supporters in City Council, but most were reluctant to challenge White.

Wrote columnist Dick Feagler: “I like Helen Smith. I think she would make a good mayor. It is her misfortune that Cleveland already has a good mayor.”[59] It was also her misfortune that the Indians made it to the World Series that fall, providing White, in full Indians regalia, lots of free photo opportunities while Smith struggled to get voters focused on her issues and her candidacy.

Smith gave White a run for his money. He spent plenty of it and was later fined $500 for exceeding campaign limits. She won 39 percent of the vote in the first real political challenge to White since his first win in 1989. The votes fell along familiar racial lines. White carried all the East Side wards except two, where Councilmen Mike Polensek and Ed Rybka supported Smith, and White also did well enough on the West Side to get 60 percent of the total vote. Race “is always a factor, but it was not a deciding factor,” said White’s campaign manager Arnold Pinckney. [60] Nobody mentioned Smith’s gender; by 1997, that would have been politically incorrect. In his postmortem of the election, however, Brent Larkin did mention that Smith might be “a nicer mayor” than White had been. [61]

Smith had to step down from her Council seat to run for mayor, but after her defeat, her long-time colleague on Council, Jim Rokakis, appointed her to the Cuyahoga County Board of Revision.

Conclusions

These also-rans – competent, ambitious career politicians – seldom get mentioned in stories about Cleveland’s past: written history generally sides with the victors. But these women’s shared fate says much about Cleveland politics. All lost the mayor’s race in a city where ethnicity and race often trumped party affiliation and almost everything trumped being female. Their gender was “always a factor” – to borrow from political analyst Pinckney – although certainly more of a factor in 1961 than in 1997. Very occasionally being a woman was an advantage; more often, it was a limitation. And always, a woman’s political fortunes were closely linked to her powerful male colleagues.

Albina Cermak, Jean Murrell Capers, Mercedes R. Cotner, and Helen K. Smith nevertheless played a man’s game and played it well, starting at the grass roots and working hard to get to the top. Their long service to their constituents, their city, and their parties was acknowledged and rewarded in their post-mayoral careers.

In the longer run, their importance is two–fold. First, they kept incumbent officeholders on their political toes and gave Cleveland voters a choice in a what was essentially a one-party town during these decades. Second, they left a legacy of expanded political opportunity for other women.

And then in 2001, more than eight decades after women got the vote and exactly four decades after Cermak’s trail-blazing campaign, Jane Campbell was elected Cleveland’s first female mayor. She did not emerge from City Council but had served six terms as a state legislator, where she became a vocal advocate for women’s and children’s issues; she then served five years as a Cuyahoga County Commissioner. She was a founder and executive director of WomenSpace, the first shelter for battered women in Ohio, and became a lobbyist for the Equal Rights Amendment.

Her election represented a triumph for feminism. But it was a short-lived triumph. Campbell, although white, had an excellent record on civil rights. Nevertheless, she won only 30 percent of Cleveland’s black vote; the rest went to her opponent Raymond C. Pierce, an African-American political unknown who hadn’t lived in Cleveland for ten years. In 2005, after struggling with the financial mess and political scandals left by the White administration and a national economy in disarray after 9/11, Campbell lost the mayoral race by ten points to Council President Frank Jackson, winning only 24 percent of the black vote and losing the support of white Council members, who campaigned for Jackson on the city’s West Side.

Her victory had made Campbell the best-known woman in Cleveland politics. Yet she was following in the footsteps of these less well-known women: Albina Cermak, Jean Murrell Capers, Mercedes R. Cotner, and Helen K. Smith. And so will the women in Cleveland’s future who will also run.