top: Plain Dealer photo; bottom: CSU Special Collections

The pdf is here

Ray Shepardson: The Man Who Relit Playhouse Square

By John Vacha

“I didn’t have a clue as to what I was doing,” Ray Shepardson would recall many years later. Yet he had quit his day job in a quixotic attempt to rescue a row of shuttered movie houses on what Cleveland had once called Playhouse Square.

Tall and spare, with boyish looks of twenty-six, Shepardson was a bit young to be undergoing a midlife crisis. He had come to Cleveland from the state of Washington in 1968 to work for the Cleveland Public Schools as an assistant to the superintendent of schools and was looking for a place where teachers might gather in a social setting. Someone mentioned the four recently closed movie palaces on Euclid Avenue, so he decided to check them out and gained entry into the State Theatre on February 5, 1970. Even stripped for future demolition, it was unlike anything Shepardson had ever seen. One thing that remained in place, on the walls of a 320-foot lobby worthy of Versailles, was a series of colorful murals by James M. Daugherty dedicated to the arts of four continents. Four weeks later, fate placed a copy of the latest issue of Life magazine in Shepardson’s barber shop. On its cover, illustrating a feature on the vanishing “glory days” of Hollywood, was a full-color reproduction of Daugherty’s “The Spirit of Cinema” mural from Cleveland’s State Theatre.

“What did it was those wonderful murals,” recalls Elaine Hadden, who would become one of Shepardson’s staunchest supporters. “Ray took that as a message from heaven.” He moved into the Chesterfield Apartments, just a block or two from the State. By the end of the school year he had left the Board of Education. He doesn’t recall clearly how he supported himself at first, except that “It wasn’t easy.” For one stretch he actually lived in the State Theatre. “Buckminster Fuller was a major influence on me,” says Shepardson of the futurist architect. “He said, ‘Do something big enough to make a difference.'” Another early supporter, John Hemsath, once described Shepardson as “probably the most intense character I’ve ever met . . . .He had the personality of a pioneer, the self-confidence and perhaps the naivete to do what couldn’t be done.”

Shepardson, who had established relations with the area’s newspapers through his position with the schools, got the word out about the need to save Playhouse Square. “There was never anything but one hundred percent support from the media,” he says, making specific mention of William F. Miller of the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Herb Kamm of the Cleveland Press. School superintendent Paul Briggs, far from resenting his former assistant’s decampment, helped with his press campaign. By July Shepardson had formed a Playhouse Square Association, hoping to recruit supporters with memberships pegged at $120. Kay Halle, tireless promoter of causes both in Washington and her native Cleveland, introduced Shepardson to a largely feminine luncheon at the Intown Club. (In a flash of prognostication, he mentioned the possibility of installing a supper club in the lobby of the State.) Four months later he was telling the downtown Rotary Club that Playhouse Square could become another Lincoln or John F. Kennedy Center.

Saving the theaters was only half the problem – – and maybe the simpler half at that. In order to get some of the city’s heavy hitters on their team, Shepardson and his volunteers had to show there was a use for them. After all, the reason the theaters had gone dark was because people had stopped coming downtown to see movies. It may have started with a Supreme Court decision in the 1950s barring the big movie studios from theater ownership, which deprived downtown movie theaters of their former prerogative on first-run movies. A much larger and encompassing problem was the postwar rush to the suburbs, which soon acquired department stores, restaurants, and movie houses to rival those of downtown. Like a row of falling dominos, the theaters of Playhouse Square went dark: first the Allen in 1968, followed in short order by the Ohio, State, and finally the Palace. Little was left downtown but offices, which closed up shop at five o’clock, leaving the only lights to be seen at night the ones turned on in the upper floors by the cleaning crews. Suburbanites began bragging to one another about how many years it had been since they’d been downtown. Even Elaine Hadden, when she first heard Shepardson’s pitch, told him he was out of his mind. “Nothing can be done for downtown Cleveland,” she said. “It’s too far gone.” Still, his salesmanship overcame her resistance, and she signed on.

Another of Shepardson’s early volunteers was Zoltan Gombos, publisher of Cleveland’s Hungarian-language newspaper, Szabadsag. A European cosmopolite by birth, Gombos saw a lively downtown cultural and entertainment scene as a vital component of urban civilization. He and Shepardson decided to test the willingness of Greater Clevelanders to venture downtown by sponsoring a series of special events in Playhouse Square. To kick off the enterprise, they booked the touring Budapest Symphony Orchestra for a concert on November 21, 1971, in the Allen Theatre, the only one of the four houses then available. Putting his money where his mouth was, Gombos agreed to underwrite the concert against any loss. It couldn’t have set him back for much, as a capacity crowd of nearly three thousand turned out for the gala event.

Shepardson and his band of believers followed up this initial success with a wide range of attractions over the next few months. They included more hits as well as a few misses. A ten-night stand by the Sierra Leone Dance Company did well, but a Czech art film drew sparse audiences during a two-week run. A concert by the Prague Symphony Orchestra had to be cancelled after a breakdown in the Allen’s heating system. A concert by British actor Richard Harris, also underwritten by Gombos, produced another sellout.

From an improvised office off the Allen’s lobby rotunda, Shepardson directed an association grown to some four hundred members but expressed the need for more support “from the top.” It was said that the city’s business community, believing that Shepardson was too visionary about the theaters’ future, was reluctant to commit the millions required for their renovation. As outlined by Shepardson, his vision for Playhouse Square saw the Palace as a large concert hall and opera house, the Ohio as a venue for chamber concerts and experimental theater, and the State as a supper club-restaurant-night club complex. As for the Allen, it would be converted into three smaller movie houses of varied sizes.

Then, quite suddenly, it appeared more likely that the State and Ohio would become venues for the parking of cars. In May of 1972, the owners of the two theaters announced that they would be taking bids for their demolition. Though they talked of eventually redeveloping the site for an entertainment and retail complex, their immediate plans envisioned nothing more than an 88,000- square-foot parking lot. To Shepardson. the news created a “crisis situation” for his campaign to save Playhouse Square. Outcries against the threatened demolition also came from the community at large. “No one comes downtown to patronize a parking lot.” protested the Plain Dealer.

As in the westerns that once filled the theater screens. the cavalry came in timely fashion to the rescue, albeit in the uncavalrylike form of the Junior League of Cleveland. Founded by local clubwomen in 1912. the Junior League hitherto had been known for its promotion of volunteerism in women’s, children’s, and education causes. Shepardson had already met and lobbied many of its members through the salon conducted by Kay Williams, a Cleveland arts patron. Elaine Hadden, outgoing president of the Junior League. had also been the first president of Shepardson’s Playhouse Square Association. Earlier that year the Junior League had sponsored its first decorators’ showcase. Which produced a windfall of $65,000 for its treasury. At its annual meeting, only days after the news broke about the demolition plans, the League voted to devote $25,000 to the effort to save the theaters. “We could see what Ray was trying to do was a valid idea,” says Mrs. Hadden, who relishes the League’s initiative as an example of “the growing power of women.”

From the start, the League’s grant was viewed as a magnet to attract matching funds. Six individuals shortly came up with additional $25,000 contributions. To this day Elaine Hadden can call the roll without benefit of notes: Ray Armington of the Cleveland Foundation, Dick Baker of Ernst and Young, Don Grogan, R. Livingston Ireland, Alfred Rankin . . . She and her husband John gave a double pledge of $50,000. “Ray Armington said it was used over and over again,” observes Mrs. Hadden of those pioneering contributions. Various holding tactics were employed over the next few months, including a thirty-day stay negotiated by the City Planning Commission. By the end of the year a group of civic leaders formed a Playhouse Square Operating Company to lease the State and the Ohio. According to their spokesman, Hugh Calkins, “All that we have done is to buy some additional time in which we can try to decide whether something constructive can be done.”

To Ray Shepardson, the eternal optimist, it looked “like the ball has started to roll rather than swing.” He meant the restoration ball, not the wrecking ball, and without realizing it, he was about to give it a decisive shove. It started with a visit every bit as serendipitous as Shepardson’s initial discovery of the State lobby. This time he went to see a show at neighboring Cleveland State University called, in the long-titled vogue of that time, Jacques BreI Is Alive and Living in Paris. It was performed in the lecture hall of the Main Classroom Building. Shepardson caught it on the last night of its run in February, 1973, and was overwhelmed by its modern madrigals of love and war.

After the final bows, Shepardson sought out the director. Joseph J. Garry, Jr., head of Cleveland State’s theater department, had originally produced the show the previous year for the Berea Summer Theater before bringing it to CSU with the same cast. Something like the following exchange ensued:

SHEPARDSON. I want you to come and do it in our cabaret.

GARRY. I didn’t know you had a cabaret.

SHEPARDSON. We will.

At the time Shepardson didn’t have a theater ready, but over at the State he had perhaps the largest theater lobby in the world. He had a dais built in the center and filled the rest with tables and chairs. His stage was little more than a platform, but that and an audience were all that actors ever needed to put on a show. He had the cast from Berea and CSU. All he needed was an audience. He had built it, but would they come?

Jacques Brel Is Alive and Living in Paris opened in the Playhouse Square Cabaret during Holy Week on April 18, 1973. “It’s a collection of perceptions, truths, and insights into the human condition–a modern French counterpart to Moliere, Rabelais, and Voltaire,” says Garry of the show. Performing the songs of the Belgian composer Brel were Providence Hollander, David O. Frazier, Theresa Piteo, and Cliff Bemis – – four names as embedded in Playhouse Square lore as those of the original cast of Oklahoma! in the annals of Broadway. “On a small black stage that has been constructed on one side of the old lobby, four perfectly lovely people . . .made perhaps the most powerful contact with an audience I have ever experienced,” wrote Don Robertson for the Cleveland Press:

“I go to a lot of shows, and sometimes I become quite jaded.

But this production of “Jacques BreI” hit me smack in the

gut. If you care anything about theater, you absolutely

cannot afford to miss it.”

Before the days of the internet and social media, there were two paths to theatrical hits. One was the overnight sensation, in which a line would form from the box office completely around the block on the morning of rave reviews following opening night. The other took longer to catch on, depending, in the absence of Facebook, on word-of-mouth advertising.

Jacques BreI was the latter type, and it was a bit touch-and-go at first. John Hemsath went to work for Playhouse Square at that time, and in lieu of a salary was given the coat-check concession. Shepardson was greeting audiences by night and up on the roof by day, spreading buckets of tar. At the end of each night, according to Garry, they had to count the take to ensure that they could pay the waiters and barmen the next night. But Shepardson, says Garry, was “a genius at marketing.” Back in his college days at State Pacific near Seattle, he had inaugurated the school’s first cultural series, handling everything from booking to ticket sales.

Soon Jacques BreI grew from what began as a three-week stand into a show business phenomenon. Other than touring Broadway shows at the Hanna Theatre around the corner, Shepardson observed, “We were the only ballgame in town . . . .I can remember when we used to draw more than the Indians.” Joe Garry remembers it as “an extraordinary moment of the right people coming together at the right time.” Those involved were surprised at the close relationship between actors and audience. Patrons would come up afterwards to share their memories of those fabulous theaters in their heyday–coming with their parents . . . .on their first date . . . .on anniversaries and special occasions. Clearly they were returning for more than a show, no matter how good; they were also coming to recover pieces of their past. Before long repeat customers became noticeable, many for half a dozen visits or more.

After seven months, Jacques BreI passed two notable milestones. At the end of October 1973, it became the longest-running show in Cleveland’s theatrical history, eclipsing a record established in 1924. It was also said to be the longest-running dinner theater show in the history of the country. But Jacques BreI was just getting warmed up, as other milestones passed with mathematical regularity: 200, 300, 400 performances. It closed after two years and two months on June 29, 1975, having established a new Cleveland record of 550 performances. Not only had the show gotten national publicity, noted Shepardson, but “with it the restoration work in Cleveland was publicized, too.”

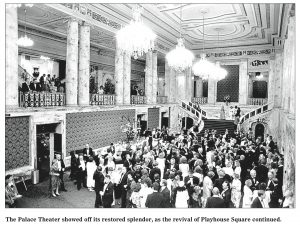

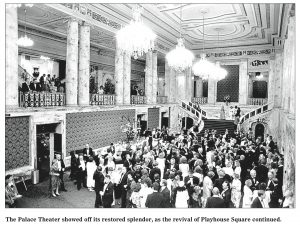

How does one follow an act like that? For Shepardson, that was a no-brainer: Put on more shows! Before BreI’s first anniversary, a revue with the even longer title of Ben Bagley’s Decline and Fall of the Entire World as Seen Through the Eyes of Cole Porter opened in the Grand Hall of the Palace Theatre. As Joe Garry said, “Every time we wanted to save another space, we created a show to put in that space.” For the show EI Grande de Coca-Cola they transformed the State’s auditorium into another cabaret. In order to receive charitable gifts and contributions for theater restoration, the nonprofit Playhouse Square Foundation was formed around this time.

Admission was free to The All Night Strut, another cabaret revue in the State auditorium, with Shepardson making a pre-show pitch for restoration contributions. “Where did, you get him? He’s good,” commented one patron to an association staffer. Taken in by the “slightly off” authenticity of his “rumpled gray suit,” she thought Shepardson was part of the show. Even as restoration proceeded in the State, a series of Vegas-style acts such as Sarah Vaughan, Mel Torme, Bill Cosby, and Sergio Mendes attracted 250,000 in attendance. Offstage, some of the stars such as Chita Rivera and Mary Travers of Peter, Paul and Mary, picked up paint brushes and joined volunteers in retouching the theater’s plaster decor. With the encouragement of Shepardson, restaurants such as the Rusty Scupper and Lucarelli’s Sweetwater Cafe began opening in the area, filling the void left by such former gathering places as Stouffer’s and Monaco’s.

In 1978 the Playhouse Square theaters gained the distinction of a listing in the National Register of Historic Places. They also came to the notice of Wolf von Eckardt, architectural critic for the Washington Post and at the time a visiting professor at CSU. “This is the story of a white elephant which has been stirring here for five years, and soon may be strong enough to pull Cleveland’s decrepit downtown out of its doldrums,” he wrote for the Post. He described how “four of the most garishly beautiful old vaudeville-and-movie palaces . . . . ever built” were narrowly saved by “Shepardson and friends” and were being lovingly restored. Cleveland had hitherto lagged behind other American cities in revitalizing its urban core, he concluded, “But if Playhouse Square, as seems more than likely, attracts large numbers of people downtown, a good many of them will decide to settle there.” People were beginning to connect the dots.

There had been one last “crisis situation” to overcome on the way to these testimonials. It came in the form of a renewed demolition threat from the owners of the State and Ohio. This time it was met by a formidable phalanx of opposition, led by a man Shepardson calls “one of the major forgotten people of Playhouse Square.” This was Gordon E. Bell, Shepardson’s college roommate, who came with him to the Cleveland schools and became one of his original Playhouse Square disciples. In 1977 he was serving as the foundation’s executive director, when the Loews Building with its two theaters again fell within the compass of the wrecking ball. Bell contacted Cleveland municipal archivist Roderick Porter, who was interested in historic preservation, and the two of them approached Cuyahoga County Commissioner Bob Sweeney, an advocate of downtown renewal. Together, they arranged for the acquisition of the Loews complex by Cuyahoga County, which undertook to renovate the four-story office building on Euclid Avenue for its own use and leased the two theaters to Playhouse Square for forty years. The city’s Kucinich Administration arranged for a $3.14 million grant from the federal Economic Development Administration to begin restoration work on the State auditorium. At the same time, Playhouse Square secured a lease on the neighboring Palace Theatre.

With three theaters under stable control, Playhouse Square began to attract the support of the city’s power structure. Under the aegis of the Cleveland Foundation, plans were made to renovate the theaters into suitable spaces for such performing arts organizations as Cleveland Ballet and Cleveland Opera. Early in 1980 Playhouse Square launched a capital drive of $18 million to implement those plans and establish a firm business basis for operating the theaters. “This is not a pie-in-the-sky program,” said Charles Raison, Playhouse Square executive secretary, “it can and must work if Cleveland is to have a night life after 5:15 p.m.” A year later Thomas E. Bier of Cleveland State’s College of Urban Affairs, in an op-ed column for the Plain Dealer, called on the city’s private sector to match the commitment of the public sector. “Redevelopment of Playhouse Square is not an ordinary opportunity,” he wrote. “It is, I suggest, in the category of those relatively few make-or-break points that come along in a city’s evolution.” Bier echoed von Eckardt in extolling an attractive downtown as a recruiting tool for bringing “educated young adults” to the city. In challenging the private sector to step up to the plate, he was also renewing Shepardson’s call for more support “from the top.”

By that time, however, Shepardson and Playhouse Square had parted ways. On Christmas Eve of 1979, a story in the Plain Dealer revealed that Shepardson was leaving the crusade he had preached and led to within sight of the promised land, and moving on “to where he can run the show again.” Ironically, his departure appeared to have been hastened by the very development for which he had been waiting: the belated support of the city’s movers and shakers, its banks, corporations, and foundations. “When the establishment began getting behind the project,” reported the Plain Dealer’s William F. Miller, “Shepardson began losing influence and power.” Specifically, a rift had opened up between Shepardson’s vision and that of the powerful Cleveland Foundation, with the latter pushing for the concept of a cultural center as opposed to Shepardson’s predilection for more popular entertainment.

“Given the sizes of the theaters and the needs of opera, ballet, and so on, the Cleveland Foundation thought we had too small a vision,” remembers Gordon Bell. “The feeling was that they wanted people with performing arts credentials.” Shepardson, too, “never dreamed it would become an arts center. I thought it would be an entertainment center where arts would be welcome; instead, it’s an arts center where entertainment is welcome,” he would note later. At the time, Shepardson moved on to work his restoration magic in other cities. His last ties to the city were cut in May of 1980, when his contract as booking agent for Playhouse Square wasn’t renewed by mutual consent.

According to Plain Dealer music critic Robert Finn, Shepardson had never had many fans in Cleveland’s boardrooms, which viewed him as “a starry-eyed nobody, and an outsider to boot.” Shepardson probably didn’t reassure them when he let his long sideburns and mustache expand into a full facial beard. He recalls that developers viewed visionaries such as himself as “broke f—–g idiots.”

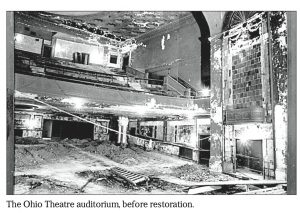

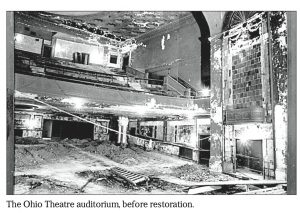

Yet Shepardson carried no grudges. Returning within a year to see the restored State auditorium, he was moved to tears. “I just could not believe it was so beautiful and that I lived to see it actually happen,” he said. In 1984, when Cleveland celebrated the formal opening of Playhouse Square Center, he sent a tongue-in-cheek testimonial: “I told you if I left town you guys would get the money.” He would call Playhouse Square under the management of his successors “the best-run performing arts center in the U.S.”

Even before leaving Cleveland, Shepardson had become involved in a campaign to restore the Palace Theater in Columbus. “I’d been there [Cleveland] long enough,” he says. “I was getting involved nationally and became a sort of fanatical preservationist.” He moved on to Cincinnati and Louisville, then to St. Louis, Portland, and Seattle. “In 1985 I was living in five cities,” he recalls. He estimates that he has played a part in some forty to fifty theater restorations, including five in Detroit alone. “Saving Playhouse Square allowed me to do world-class entertainment,” he states. “I had credibility in the industry.”

Playhouse Square meanwhile pursued its own course to become what Variety, the show business weekly, would later call a “Cleveland arts juggernaut.” In 1982 it reopened the renovated Ohio Theatre as the new home of the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival, which moved downtown from its former home in suburban Lakewood. Two years later the restored State Theatre was unveiled as the new quarters for Cleveland Ballet and Cleveland Opera. The Palace soon followed as a sumptuous venue for touring shows and performers. Nearly lost in the stir was the Allen, the site of Shepardson’s initial ventures in bringing people back downtown. Almost at the last minute, the Cleveland Foundation purchased the entire Bulkley Building complex and leased the ensconsed Allen to Playhouse Square, which restored and added it to its collection of stages.

Indicative of Playhouse Square’s success was the drafting of its president, Lawrence Wilker, to run Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. He was succeeded by Art Falco, who expanded the foundation’s vision from theaters into a theater district. A garage was constructed on Chester Avenue, an office building on Huron, and a Wyndham Hotel on Euclid Avenue. When the Hanna Building complex came on the market, it too was snapped up by Playhouse Square, which saw itsreal estate ventures as both “a working endowment for the theaters” and a means of controlling the surrounding streetscape. “The hallmark of Playhouse Square is that they realized a successful theater district could only work if there was a successful neighborhood,” Joe Roman of the Greater Cleveland Partnership told the Wall Street Journal, which extolled the newly styled Playhouse Square as “a unique business model in downtown Cleveland.”

“You might call it a pioneer. Clearly it was in back at the beginning of Cleveland’s renaissance,” stated a press secretary for former Mayor Michael White. Former Mayor George Voinovich credited it with being the city’s first public/private partnership. “The Warehouse District, the Tower City project, Gateway, the Flats, the East Fourth Street district–they all followed Playhouse Square,” recently noted Arthur Ziegler, a historic preservationist from Pittsburgh. In awarding him an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree in 2008, Case Western Reserve University testified that “The work spearheaded by Shepardson has been hailed by civic leaders as one of the top 10 successes in Cleveland’s history.”

No single individual had made it happen, but without one specific person it couldn’t have happened. Except for the timely intervention of Ray Shepardson, there would have been little left to save. “To imagine what would have happened to the city if the Playhouse Square theaters had been bulldozed . . . . is to shudder,” wrote Plain Dealer architecture critic Steven Litt.

There is a lingering perception of Shepardson as the original “forgotten man” of Playhouse Square, perhaps going back to the absence of his name from the foundation’s original souvenir book (the “Red Book”) in 1975. That omission, however, was by his choice, not Playhouse Square’s. “If it works,” he told editor Kathleen Kennedy, “they’ll know.” It does, and they do.

Back in 1879, inventor Charles F. Brush had attracted national attention by lighting Cleveland’s Public Square with his new electric arc lamps. Over the following century the lights gradually dimmed with the decline of the central city. Nearly a hundred years after Brush, Ray Shepardson was the man who turned the lights back on.

For more Cleveland Stores

For more on Playhouse Square