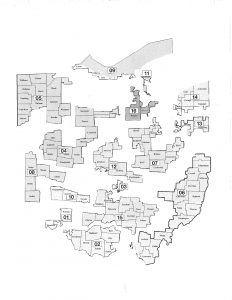

Ohio Congressional Districts “Disaggregated” 2012-2022

Gerrymandering. The art of fixing elections

by Michael F. Curtin

On Nov. 3, 2015, Ohioans voted to end the blatant gerrymandering of the state’s 132 state legislative districts – 33 Ohio Senate districts and 99 Ohio House districts.

This welcome opportunity arrived because, in December 2014 – after many decades of partisan stalemate – Democrats and Republicans in the Ohio General Assembly forged a compromise plan to put before Ohio voters.

Unfortunately, the lawmakers stopped short of putting forth a companion plan for ending the gerrymandering of Ohio’s 16 congressional districts.

Ohio is one of many states in which good-government organizations for decades have been advocating an end to gerrymandering – the art of drawing meandering, misshapen districts to ensure noncompetitive elections and, as a result, one-party dominance that ignores overall vote totals.

The U.S. Constitution, to ensure equal representation by population, requires congressional and state legislative districts be redrawn once every 10 years after completion of a new U.S. Census.

Over the decades, both major parties in Ohio and other states – when in control of the offices that draw the maps – have abused their authority.

In 2010, Democrats in control of the Ohio House of Representatives shunned a widely-acclaimed reform plan approved by the Republican- controlled Ohio Senate. Why? Because Democrats then controlled the offices of governor and secretary of state, and wrongly assumed they would retain control after the November 2010 elections.

Over time, especially with the advent of computers and sophisticated map-making software, the abuses have become more and more flagrant. As a result, at no time in Ohio history have the congressional and state legislative maps been as blatantly gerrymandered as the maps now in place until the 2022 elections.

For example, one of the most bizarre districts in American history is Ohio’s 9th Congressional District, which snakes across the Lake Erie shoreline from Toledo to Cleveland.

When it comes to our collective attempts to foster good government – honest, open, responsible government – there have been few barriers as persistent, as corrosive and as detrimental to that goal as the blatant gerrymandering of congressional and state legislative districts.

We have known this for a long time.

When John Adams, in 1780, was writing the Constitution of Massachusetts, he called for the creation of compact, contiguous districts that would not unduly split towns or wards, and that would protect communities of interest.

Despite Adams’ warnings, by 1811 political opportunism trumped political piety in that state.

That occurred when Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry (pronounced GARY) went along with members of his party and signed a redistricting bill to favor the Democratic-Republicans and to weaken the Federalists – even though the Federalists, as the majority party, collected nearly two-thirds of the votes cast in the next election.

GARY-mandering was born; the pronunciation later morphed into “JERRY-mandering.”

Massachusetts was left with many odd-shaped congressional districts, and the practice of gerrymandering was off to the races.

The practice was no stranger to Ohio.

In the late 1870s and into the 1880s, Ohio politicians redrew our state’s congressional district lines six times in seven election cycles.

One of Ohio’s most famous politicians, William McKinley, in 1890 lost re-election to Congress primarily because of gerrymandering.

The following year – 1891 – statewide elections in those days were in odd-numbered years – McKinley was elected governor of Ohio. In his inaugural address of January 1892, he took the opportunity to strongly condemn the practice of gerrymandering, which he had painfully experienced.

Gerrymandering was getting enough of a bad rap that by 1901, Congress passed a law to require that districts be compact. However, subsequent violations of that requirement routinely were ignored.

Unfortunately, there are no federal standards that apply to political gerrymandering, except that districts have nearly equal populations. There are federal standards that apply to racial gerrymandering, but not partisan gerrymandering.

This lack of a federal standard has been lamented by many of our U.S. Supreme Court justices over the years, including current Justice

Anthony M. Kennedy, who has remarked: “It is unfortunate that when it comes to apportionment, we are in the business of rigging elections.”

So, without a federal standard, the constant battle to curb the evil of gerrymandering is a state-by-state battle.

How is gerrymandering used to rig elections?

A concise explanation appeared in the April 2002 edition of The Economist. Here is how the magazine explained it:

“Imagine a state with five congressional seats and only 25 voters in each district. That makes 125 voters.

“Sixty-five are Republicans; 60 are Democrats. You might think a fair election in such a state would produce, say, three Republican representatives and two Democrats.

“Now imagine you can draw district boundaries any way you like. The only condition is that you must keep 25 voters in each one.

“If you were a Republican, you could carve up the state so there were 13 Republicans and 12 Democrats per district. Your party would win every seat narrowly. Republicans, five-nil.

“Now imagine you were a Democrat. If you put 15 Republicans in one district, you could then divide the rest of the state so that each district had 13 Democrats and 12 Republicans. Democrats, 4-1. Same state, same number of districts, same party affiliation; completely different results.

“All you need is the power to draw the district lines.”

That is gerrymandering. It is discriminatory districting, practiced to inflate one party’s strength and dilute the opposing party’s strength. The odd shapes result from drawing lines designed to pack as many voters of the opposite party into as few districts as possible, leaving a majority of districts to be won by the party controlling the mapmaking process.

At present, Ohio’s state legislative districts are drawn by the five- member Apportionment Board, which is controlled by the governor, auditor and secretary of state. Congressional districts are drawn by the Ohio General Assembly.

The plan approved by Ohio voters on November 3, 2015 would replace the Apportionment Board with a seven- member Ohio Redistricting Commission, and require that any plan adopted by the commission have the support of at least two members of each of the two major political parties.

The plan also includes more explicit map-making standards designed to minimize the splitting of counties, cities, townships and wards. If successful, the plan would end the drawing of crazy-looking districts that are anything but compact.

At present, there are no plans to ask Ohio voters to adopt a plan to reform congressional redistricting. Republicans who control the Ohio General Assembly said such a plan should await a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court on the constitutionality of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission.

Arizona’s Republican leaders challenged the constitutionality of the commission, arguing that the U.S. Constitution gives state legislatures exclusive authority to draw congressional districts.

On June 29, 2015, the Supreme Court, in a 5-4 ruling, upheld the Arizona plan. The ruling held that a state’s legislative authority includes the electorate taking advantage of the initiative process.

Columbus native Michael F. Curtin is currently a Democratic Representative (first elected 2012) from the 17th Ohio House District (west and south sides of Columbus). He had a 38-year journalism career with the Columbus Dispatch, most devoted to coverage of local and state government and politics. Mr. Curtin is author of The Ohio Politics Almanac, first and second editions (KSU Press). Finally, he is a licensed umpire, Ohio High School Athletic Association (baseball and fastpitch softball).

Ohio House and Senate Districts 2012-2022 (Plain Dealer/NEOMG) – click here