A bumpy road to regionalism

by Jay Miller, Crain’s Cleveland Business 9/19/22

“Regionalism sounds like a disease,” David Abbott, a retired former president of the Gund Foundation, told a group of law students at Case Western Reserve University in April. “I never really liked it for that reason, but also because it’s so hard to define and it’s even harder to apply in the real world.”

Despite his skepticism, Abbott and other civic leaders in Northeast Ohio — past and present — have been trying to think and plan beyond their traditional city and county borders for more than 100 years, not always successfully. The early efforts were focused on providing public services at a lower cost and evolved to include improving the environment, transportation systems, housing and the economy. More recently, civic leaders have been thinking more broadly about regional economies.

People may live in one city, send their children to school in another and work in another county a 60-minute drive away. As important, businesses looking to relocate or open a new operation focus on the infrastructure, available real estate and talent pool in that 60-minute radius.

In 1917, the Citizens League, a government watchdog group that lasted until 2004, proposed creating a metropolitan government for all of Cuyahoga County. At the time, only a few suburbs had been created out of the county’s townships — 85% of the county’s population still lived in the city of Cleveland — and the Citizens League believed a strong county government would lower taxes and improve services.

Similarly, Akron in 1929 annexed the city of Kenmore and the village of Ellet and was unsuccessful in bids to annex Barberton and Cuyahoga Falls before the Great Depression and a change in state law. The communities sought as merger partners typically feared higher taxes and the loss of local identity.

One reason thinking regionally might be making Abbott feel ill is that, for much of the 20th century, Northeast Ohio was not actually considered a region. Instead, it was five cities, and then five metropolitan areas — Akron, Canton, Cleveland, Elyria-Lorain and Youngstown — surrounded by small towns and farmland.

That statistical breaking of borders came about in 1949 when the U.S. Census Bureau created the “standard metropolitan area,” acknowledging that the automobile and its freeways and the expansion of economic activity into suburban areas had created interconnected communities beyond city and county borders.

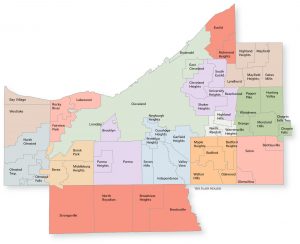

That led to the creation of organizations such as metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) — which allocate federal transportation dollars — and regional councils of government, which perform a variety of services for member communities. Unlike most regions, Northeast Ohio has four MPOs — the Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, which serves Summit and Portage counties; the Eastgate Council of Governments, serving Mahoning and Trumbull counties; the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, which covers Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain and Medina counties; and Stark County Area Transportation Study serving Stark County.

Then came the recession of the early 1980s, when the cities of the Midwest’s Factory Belt turned to rust. Cleveland lost 12,000 manufacturing jobs, and Akron lost 10,000 jobs in its rubber and plastics industry. That led to steep declines in population. According to an analysis by the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit research group, by 2007, Cleveland had lost 28.9% of its 1980 population while Akron lost 14.9%, Canton lost 26.4% and Youngstown 40.3%.

At first, after the recession, communities continued to focus on finding more local tax dollars. In Summit County, Akron pushed legislation through the state legislature in the early 1990s that allowed a city to join a development district with a township. The new structure was called a Joint Economic Development District, or JEDD. Since Ohio townships can’t levy income taxes, the JEDD allows the two communities to share the tax revenue on commercial development in the township.

Those consolidations of public services are still few and far between because many communities continue to see collaborations, where their name may be obscured by a bigger name community, as a loss of local identity and independence.

In 2002, regional business leaders, led by the late H. Peter Burg, then chairman and CEO of FirstEnergy Corp., began talking about creating a nonprofit that would bring together economic development efforts in Northeast Ohio. “The time for a more regional approach may have been right for some time, but we didn’t have the vehicle to drive it home,” Burg told Crain’s at the time. Rather than emphasize the virtues of particular cities or counties to businesses in and outside Northeast Ohio, Team NEO would sell as a single market the 13 counties in the new group. “Our focus is to find what companies need and then find where in the region that need can be met,” Burg said.

Among the groups that helped shape and fund the new organization, which opened shop in January 2003, were the Greater Akron Chamber, the Greater Cleveland Growth Association, the Lorain County Chamber of Commerce, the Stark Development Board and the Youngstown/Warren Regional Chamber. The 13 counties in the region were Ashtabula, Columbiana, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain, Mahoning, Medina, Portage, Stark, Summit, Trumbull and Wayne.

Team NEO focused only on attracting businesses to the region, leaving local chambers of commerce and public development agencies to help existing businesses in their areas expand. But it didn’t work out as planned, Crain’s reported in 2011, as public officials and local economic development organizations resisted giving up their role as leaders for their communities’ business attraction. “It was passive aggressiveness done in a beautiful fashion,” Ned Hill, dean of the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University at the time, said recently.

About the same time, in 2004, a group of 28 philanthropies and businesses committed $30 million to create a nonprofit, the Fund for Our Economic Future, to build stronger ties between the shrinking cities and the region, and to shake off the rust. “We’ve been individual cities, competitive with each other, very parochial, and that doesn’t sell in the 21st century,” said Robert Briggs, then president of the GAR Foundation in Akron. Specifically, the Fund began with aspirations to be the place where regional economic strategy — looking at issues such as stimulating entrepreneurship and improving transportation links and higher education — was hashed out. But that didn’t pan out.

“I think when the Fund first got started, it was trying to be the keeper of the regional strategy with a portfolio of economic development (projects), but it was just too unwieldy,” said Brad Whitehead, who served as the Fund’s president from its founding in 2004 until 2020 and is now a senior adviser. “We have thriving sector partnerships (in areas such as manufacturing) that are sub-regional but there’s not an (overall) strategy.”

However, the Fund has built a strong reputation for its work in building the skills of job seekers and connecting them with well-paid, in-demand jobs. And though it considers itself a regional organization, current Fund president Bethia Burke considers its partners on workforce issues to be local organizations.

“Workforce services aren’t delivered regionally, nor I don’t think they should they be,” she said. “But what I think has been useful is we share (ideas on) what makes local workforce delivery better.”

In 2011, Team NEO was able to firmly establish itself as the principal manager of economic development in Northeast Ohio. Then Gov. John Kasich created JobsOhio, his vehicle for channeling state incentives to induce businesses to invest in Ohio. JobsOhio then sought existing regional organizations to be its partner around the state. It chose Team NEO to oversee economic development for 18 counties, only slightly more than was planned for the original Team NEO. The added counties were Ashland, Erie, Huron, Richland and Tuscarawas.

“Companies choose to invest in Northeast Ohio because of the critical mass that exists within the 18 counties — an integrated supply chain, 7,700 manufacturing companies, 25 higher education institutions and a $240 billion economy,” said William Koehler, Team NEO’s president since 2015. “The question then is: How do we take advantage of the focus people have and their desire to invest in (their) communities, while also challenging them to lift up their eyes and recognize there are some things that are better-off if they’re leveraged regionally?”

Team NEO gained clout among the region’s mayors and economic development professionals because, as one of JobsOhio’s six regional partners, it would hold the strings on the $100 million business-attraction purse that Kasich was creating from state liquor profits to invest in business attraction and job creation. So most, but not all, local officials applauded the move.

Bob Bowman, then deputy mayor of Akron for economic development, didn’t jump on the bandwagon, not understanding how a nonprofit organization could put together the kinds of deals he was doing. “I don’t know how somebody from the private sector puts together a public deal,” he told Crain’s, conceding that politicians would be unhappy not being the center of deals. “Who gets the credit? The state always wants credit, and now the region will want credit, which was not involved until now, and there’s also the local level and all the people in between.”

Northeast Ohio, like much of the Rust Belt, continues to lag the national economy. But observers are optimistic that with Team NEO playing its regional role, the region and its communities are making headway.

Ward J. Timken Jr., former chairman, CEO and president of North Canton’s TimkenSteel and a member of the Team NEO board of directors, believes the region’s civic leaders, who he calls “leados,” and Team NEO are meshing well.

“I think all of the leados that I have been involved with through Team NEO are doing a great job,” he said, noting that many of the key regional organizations have gone through leadership changes in the last few years. “I think they’re cooperating, which is really, really important. Everybody is rowing in the same direction right now, which is great.”

Another civic leader who did not want to be named said he is more skeptical that the region is working well together, but he is hopeful.

“I’ve watched for years as the chambers have just stuck their middle fingers up at Team NEO, because as much as they need Team NEO, Team NEO needs them,” he said. “But it looks like (Bill Koehler’s) got them working together.”