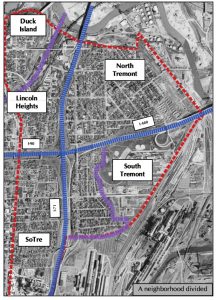

map courtesy Tremont West Dev.

The Paradox of Progress in Tremont, Ohio

By Dawn Ellis

What does progress look like and how is it measured? What is gained and what is lost in the name of progress? For the city of Tremont, Ohio, for decades, progress was defined through the destruction of neighborhoods, social capital and community cohesion. Long-term Cuyahoga County Engineer Albert Porter envisioned progress in terms of rapid, individual automobile transport from the Central Business District to the suburbs. During his almost 30-year tenure (1947 to 1976) he would oppose a city subway plan and endorse and establish most of the current highway system linking Cleveland to the suburbs. To encourage the supposed good of increased access to the Central Business District of Cleveland from the outlying suburbs through the construction of highways, Tremont was eventually carved into 4 quadrants that now attempt to relate to each other as the whole they once represented.

If Tremont will be successful in recapturing the sense of cohesion it previously had remains to be seen, but the question that lingers is: how do we as citizens determine the best use of our land, and how do we value the intangibles such as social capital and collective memory against financial and economic gain?

The Tremont area, 3.3 square miles bounded roughly by the Cuyahoga River to the east and north, West 25th Street to the west and the Harvard Denison Viaduct and Riverside Cemetery to the south, was settled in 1818 by Seth Branch and Martin Kellogg, from New England. It began as more of a colony within the city of Ohio City but would eventually merge with Cleveland in 1854. The area grew slowly. The Reverend Asa Mahan (then president of Oberlin) envisioned Tremont’s acres as a cultural center not only for Cleveland, but all of Ohio. Reverend Mahan, with landowners Seth Branch, Martin Kellogg, H.R. Hadlow, Hiram Aikens and Brewster Pelton, moved forward with a plan to establish a university in the area.

“University Heights” as an idea in 1850 would be laid out with neighborhoods and streets plotted, inspired by the vision of bucolic serenity and high culture. University, Professor and College were some of the first plotted street (these streets still exist in Tremont), names chosen to reflect the educational and cultural aspirations of the settlement. The university idea would eventually fail but University Heights became an exclusive residential area with impressive historic architecture whose Franklin Avenue rivaled the famous Euclid Avenue on Cleveland’s east side.

The War of 1812 had helped establish Cleveland as a trade center and by the 1820s the port was a successful commercial hub. In 1832 the Ohio and Erie Canal, of which Cleveland served as the terminus, was completed and some of the commercial promise of the lake was realized. By 1849 with the completion of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland’s prosperity and growth were intimately tied to transportation, first through the canal, then through the railroads, and finally through the automobile industry.

The Civil War period proved immensely transformative for Cleveland. By 1860 there were five railroad lines that ran in and out of the city; it was well positioned to profit from the trade in raw materials and other goods. At the turn of the century Cleveland’s important industries of iron, steel and oil refining played a part in the city’s entry into the emerging automobile industry. Its combination of access to raw materials, a burgeoning manufacturing base and a solid class of well-to-do consumers helped make Cleveland a leading automobile city in the United States. Spurred by the work of such people as Alexander Winton, who introduced his first car to Cleveland in 1896, the automotive and automotive parts industry played a large role in the commercial development of Cleveland. Automakers such as Winton, Peerless and Baker Electric helped solidify the importance of the automobile in northeast Ohio and Cleveland.

Over the years Tremont’s upper scale residential atmosphere gave way to the development of such industries as steel making and oil refining that led to an influx of immigrant workers to the area and an exodus of the New England families that had settled the land, who continued to move south and west, towards suburbs like Parma. One of the earliest industrial establishments, the Lamsom-Sessions Company, a bolt manufacturer in 1869, helped lure a diverse population to this part of Cleveland. Towards the second half of the 1800s, parcels in Tremont were among the most affordable in the area and working class families were able to purchase homes, or land on which to build homes, that were near their places of employment; visions and plans of grand estates and gardens gave way to working class residential and industrial neighborhoods.

New immigrants could establish veritable ethnic enclaves within Tremont; families could live, work, worship and shop among fellow immigrants. Among the first of these immigrant groups to settle in Tremont were the Germans and Irish, who concentrated themselves in the lowlands. German and Irish were followed by Polish, Greek, Ukrainians and Puerto Ricans-more than thirty nationality groups have lived in Tremont over the years. The legacy of these different groups can still be found in the architecture of the housing that reflects a variety of styles such as Victorian and Queen Anne.

Unfortunately the ethnic and class cohesion that Tremont experienced did not protect it from the suburban drain that began to empty the urban areas across the country by the 1930s. Despite the grandeur of Franklin Avenue and its impressive churches, Tremont was not an overall affluent section of Cleveland. The conditions of working class industrial regions were sometimes poor and the economic devastation of the Depression hit working class communities like Tremont especially hard. Some homes had no running water well into the 1950s, and houses built for single family occupancy served twice as many people as intended.

Congestion and poverty were rampant, and by 1939-40 Tremont was slated for governmental intervention in the form of a public housing development known as Valley View Homes. This is the map of the location of the development.

This project was seen at the time as a public service and residents were generally receptive to this sort of governmental program. The plight of the 250 families that were displaced as a result of this project foreshadowed what would transpire repeatedly in Tremont.

As property values fell and population numbers decreased throughout the 1950s, Tremont become a prime candidate for the urban renewal projects (often designed to facilitate the flow of vehicular traffic in and out of the Central Business Districts of cities) that spread over the nation that combined the construction of highways and housing developments with mass razing and resident relocation in an effort to combat slums and urban blight. Financially able residents had been leaving the area for southern suburbs since the late 1800s, yet at that time, more people were entering than leaving Tremont and the population continued to rise until its peak of 36,686 residents in 1920.

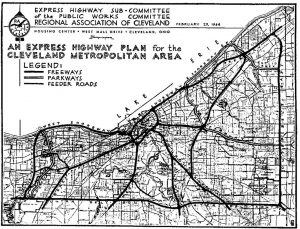

Cleveland’s Freeway Plan of 1944 (that followed an earlier plan proposed in 1940) was designed as a multimillion dollar integrated freeway system to relieve downtown congestion.

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Kent State Univ Press, 1990)

Cleveland’s overall urban renewal plan was the largest in the United States and targeted more than 6,000 acres east of the Cuyahoga River in the inner city. By 1966 the Department of Housing and Urban Development had authorized assistance for seven urban renewal projects in Cleveland: Longwood, St. Vincent’s Center, Garden Valley, East Woodland, Erieview 1, University-Euclid 1 and Gladstone, that represented a mixture of rehabilitation, clearance and redevelopment for residential and commercial use.

Cleveland’s General Plan of 1949 under the City Planning Commission of Chairman Ernest Bohn and Director John T. Howard, provided a framework for what was intended to be a redevelopment of the city. The Plan focused on “protection, conservation and redevelopment…aimed at establishing good living standards for every home neighborhood in our city and making decent housing available for all families at prices and rents they can afford to pay”. A critical component of this plan would be slum clearance and it was estimated that 13,000 Clevelanders would have to be relocated from lands and neighborhoods.

Through the Housing Act of 1949 the city was authorized to purchase property in designated blighted areas in order to clear it and sell it to private developers at a reduced price, with the federal government absorbing much of the true cost of the project. The overall intention of the program was to spur construction of improved low-income, public housing in targeted areas, Unfortunately newly constructed housing units never numerically equaled the destroyed units and urban cores struggled to entice people back to the inner city.

Bolstered by the 1954 Berman v. Parker decision of the Supreme Court that expanded the scope of eminent domain (the power of the government to take private property in return for reasonable compensation) and its applicability in urban renewal projects, planners and housing reformers had a powerful tool with which to reshape American cities and society. As planners correlated blighted neighborhoods with public nuisance, and condemnation and re-development with the public good, it became easier to justify private property seizures in increasing numbers. Once coupled with the incentive provided by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 that provided for a system of 41,000 miles of roadway to be financed through a Highway Trust Fund (developed through the excise tax on fuel and tires), the partnership between urban renewal and highway construction became solid.

In the early 1960s Tremont was one of eight targeted neighborhoods in Cleveland for the neighborhood Improvement Program that had developed from the City’s Workable Program of the late 1950s. These programs were designed to control the spread of blight and slums. Blighted parcels and slum neighborhoods could be defined by states of deterioration, age and obsolescence, inadequate provision for ventilation or open spaces, unsafe and unsanitary conditions, overcrowding of buildings on the land and excessive dwelling unit density.

Tremont, through its age, primary population and historic function, fell into this definition of a blighted neighborhood and its voluntary participation in the Workable Program signaled its willingness to authorize a certain amount of clearance and redevelopment as was intended by the program.

Howard Whipple Green’s census of 1954 revealed that 87 to 100 percent of the housing stock in 8 of the 9 tracts that comprised Tremont was built before 1920 and that no new housing was being built. In 1960 the 8459 housing units in Tremont included more than 300 “miscellaneous” dwellings that were often shacks or conversions.

Neighborhood destruction in Tremont for freeways began with the Innerbelt Bridge at Abbey Avenue and West 14th Street in 1941. Unlike their southern neighbors of Brook Park (who unsuccessfully resisted the planned path of the freeway), Tremont did not wage a sustained campaign against the Medina Freeway (I-71). The residents seemed to belong to several schools of thought: one group was ready to leave and willing to accept any fair price for their property to sell it, they were ready to leave the crime, congestion and pollution of the neighborhood and perhaps move further south into cleaner, less dense suburbs such as Parma.

Another group was nervous about the change but did not want to stand in the way of “progress” and a third group, made up of the poorest of Tremonters would see their lives torn apart as their neighbors left and the businesses they had frequented for years closed. Residences with several generations were split up as they did not receive enough money to buy new houses to accommodate their family size. The sense of community, the familial ties, social capital were all taken from this group.

By the 1970s the massive slum clearance and forced relocation approach to urban renewal was becoming less popular with governments and the public. Revolts in such cities as San Francisco, New Orleans and Shaker Heights, Ohio had successfully fought against interstates plans in their areas. Highway construction enthusiasts like Albert Porter’s highway vision would not extend to Shaker Heights and this defeat signaled the coming decline of the supremacy of this urban planning phase.

The Tremont area’s historic importance lies in its being one of the oldest and most densely built neighborhoods in Cleveland- the very qualities that are compromised by large scale land clearance. Its settlement also reflects the broader national pattern of industrial progress and immigration. Tremont was the site of the largest of Cleveland’s seven Civil War camps, Camp Cleveland, and it is included as part of the Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor.

Tremont is also listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is a local landmark as proof of its representation of a pivotal period in U.S. history. The architectural richness of the residences that reflect several styles and the historically ethnic church stock (including landmarks such as the United German Evangelical Protestant Church, the Holy Ghost Byzantine Catholic Church and St. Theodosius) are important visual links to the development and history of Cleveland.

The crusade of using highway construction as a tool in the scheme of progress known as urban renewal and slum removal has lost some of its moral urgency and authority, but there still remains the thought that improvement for economically challenged neighborhoods consists in highway construction and resident displacement. Whether Tremont’s history will influence future decisions on the unintended costs that come with this sort of progress remains to be seen. Perhaps the story of Tremont will come to mind as we debate the merits of such projects as Opportunity Corridor and consider the value of people space versus car space, and investigate how much of our land should be dedicated to going somewhere instead of being somewhere.