TOWARD EQUAL PARTNERSHIP:

THE GREATER CLEVELAND CONGRESS – INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S YEAR

by Marian J. Morton

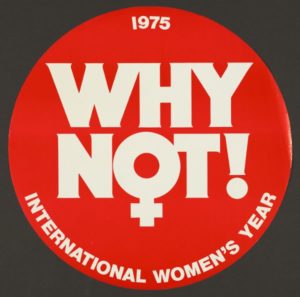

“THRONGS OPEN IWY CONGRESS,” exclaimed the Cleveland Plain Dealer on October 26, 1975.[1] The throngs included men, but most of those who crowded into the Cleveland Convention Center were women – old and young; single, married, or divorced; of many religious faiths; black and white, Hispanic and Eastern European; housewives, nurses, lawyers, teachers, social workers, artists. They came on the opening Saturday of the Greater Cleveland Congress – International Women’s Year, then Sunday, and then Monday – 45,000 of them – to applaud the celebrities, to learn from the workshops and lectures, to enjoy the dance and music. And mostly to join in solidarity with other women – it was called “consciousness-raising” back in the 1970s –as they sought equal partnership with men. Cleveland was hosting the biggest IWY celebration in the country. Those were heady days, another beginning in the long fight for equality for women.

WHAT CAME FIRST

The immediate impetus for the congress was a 1972 United Nations resolution, more than 30 years in the making, declaring that 1975 would be International Women’s Year; the goal would be to create a society in which women would have full and equal participation in social, economic, and political life. The resolution was supported by Presidents Nixon and Ford.

But the UN resolution, and the Cleveland congress, came more than a century after 300 women and men gathered in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, the official beginning of the women’s rights movement in this country. Inspired by their participation in the movement to free slaves, they re-phrased the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident- that all men and women are created equal.” They asked for equal rights before the law, in education, employment, and churches. And – most controversially – they asked for the vote. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was one of the brave few to offer support.

The Seneca Falls demands were eloquently re-stated at a woman’s rights convention in Salem, Ohio, in 1850, and in 1851, in Akron, where former slave and anti-slavery activist Sojourner Truth delivered her dramatic, often-repeated speech, “And Ain’t I A Woman?” There is some about question about who actually wrote the speech, but no question that it ridiculed the many who claimed that women were too weak and too stupid to have equal rights and that, as further evidence, Christ wasn’t a woman. “And where did your Christ come from?” Truth famously replied: “From God and a woman. Man had nothing to do with Him.”

In the post-Civil War period, in the context of national attention on enfranchising black men, the movement for women’s rights began again, focusing its own attention on the vote – becoming, in effect, the suffrage movement. In Cleveland in 1869, Lucy Stone, an Oberlin graduate, and her husband Henry Blackwell, founded the American Woman Suffrage Association, the moderate wing of the movement. In 1890, the association merged with the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, led by firebrands Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, to form the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The NAWSA led the suffrage movement for the next three decades.

These were decades of progress as women in Cleveland, like women elsewhere, entered the work force, most in industry, some in offices; an elite few went to colleges like Oberlin or Western Reserve’s College for Women; some even entered the professions.[2] Cleveland women also entered public life through the backdoor – the myriad of women’s organizations like the YWCA, the Consumers League of Ohio, the Women’s City Club, and the Junior League. Although there were small political victories – Ohio women got the right to vote for and serve on school boards in 1894 – , woman suffrage amendments to the Ohio Constitution were defeated in 1888, 1890, and 1891.[3]

Cleveland suffragists organized in 1910 and braved public scorn by speaking from soap boxes in rough neighborhoods and outside factories, distributing pamphlets, marching in lively parades, and debating the vocal, plentiful anti-suffragists. Suffragists did win the support of local politicians, including Tom L. Johnson and Newton D. Baker. Nevertheless, efforts to get the Ohio legislature to enfranchise women failed in 1912, 1914, and 1917. Cleveland suffragists sided with the moderate NAWSA when radical suffragists picketed the White House and went to jail, and they rejoiced when 26 million women finally got the vote with the passage of the 19thAmendment in 1920, a long, exhausting 72 years after Seneca Falls.

The Cleveland suffrage movement produced two national leaders: Florence E. Allen, the first woman to be elected to the Ohio Supreme Court and first to be appointed chief justice of any federal court, the 6th Circuit; and Belle Sherwin, who served from 1924 to 1934 as president of the new national League of Women Voters. The league began its work of educating the new voters to participate in politics.

And then still another beginning – an echo of the nineteenth century – when the civil rights activism of the 1950s and 1960s inspired another movement for equality for women. These women called themselves feminists – a nod to an earlier generation who wanted the vote but had broader goals. Women’s potential political importance, as they continued to enter the work force, higher education, and elected office, was acknowledged in the 1963 Equal Pay Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s prohibition against sex discrimination in employment. In 1966, women and men, chafing at the slow pace of change, established the National Organization of Women (NOW). Its signature goal became the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The ERA had been introduced to Congress in 1923 by the National Woman’s Party, the left wing of the suffrage movement; some of them had also picketed the White House. The amendment was sporadically endorsed by both the Democratic and Republican parties until it was shelved in the mid-1950s.

NOW resurrected the ERA from political oblivion. The amendment stated that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex.” It had been initially opposed by women’s groups like the LWV that feared it would eliminate the laws that gave women special protection in the workplace or in marriage. By the early 1970s, however, many women’s organizations endorsed it. And by 1975, NOW had become the most visible face of feminism. Its motto, “toward equal partnership with men, “ emphasized cooperation, not war, between the sexes.

Cleveland women organized a local chapter of NOW in 1970 and then a flurry of new feminist organizations. These included the Women’s Equity Action League, the Cuyahoga Women’s Political Caucus, the Cleveland Coalition of Labor Union Women, the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center, and Women Together.[4] All would be part of the IWY congress.

THE CLEVELAND CONGRESS

Congress planners were well-established, well-connected volunteers and professionals. Chairperson Gwill York was a past president of the Junior League and sat on the boards of a half-dozen prestigious, non-profit institutions. York was aided by Muriel Jones and Barbara Rawson, both with the Cleveland Foundation, and Evelyn Bonder, director of Project EVE (Education, Volunteerism, and Employment) at Cuyahoga Community College. Planning meetings began in August 1974 and continued for more than a year, ultimately engaging dozens of women in the process. All were volunteers.

These women knew their Cleveland audience. York predicted that the Cleveland congress would be a great success: “You have extremists on the West Coast and the East Coast, but here in the Midwest … is a beautiful place where things are handled in a very rational way.”[5] According to a Gallup poll of Cleveland women taken just prior to the congress, the “largest proportion” felt that “marriage and children without a job [was] the ideal situation” although especially younger women felt that a job could be combined with marriage and children. Black and low-income women found the combination less desirable – or simply less possible. Only 44 percent believed there was job discrimination; 85 percent believed that women had equal opportunities to get an education.[6] The congress’s adoption of NOW’s moderate goal of “equal partnership” was intended to appeal to these women.

The planners also knew how to raise funds, a perennial challenge for women’s organizations. The Junior League, the YWCA, and the Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine contributed. The Cleveland Foundation donated funds and lent an office –and its prestige. Other foundations and businesses, including banks, industry, and retail establishments like Halle’s and Higbee’s, followed suit, as did the Cleveland AFL-CIO. Dozens of exhibitors, both commercial and non-profit, paid for booths to advertise their goods and services. The grand total raised: more than $100,000, which did not count volunteer hours or donated services.[7]

More than 300 women’s institutions and organizations participated. They represented a range of political views from Women Speak Out for Peace and Justice and the Socialist Workers Party to the Cuyahoga County Republican Women’s Organizations. They had differing religious affiliations – the National Council of Jewish Women, the B’nai Brith Women’s Council, the Sisters of St. Joseph, the Eastern Orthodox Women’s Guild – and came from different ethnic backgrounds – the Karamu Women’s Association and the Ukrainian Gold Cross. Professional women were represented by the Women’s Clergy of Greater Cleveland, the Women Historians of Greater Cleveland, the Greater Cleveland Nurses Association, among others. Groups also addressed long-standing economic inequities: the National Welfare Rights Organization and the Domestic Workers of America.[8]

The panels and workshops expanded upon familiar themes. There were seventeen on equality in the workplace, more than on any other topic. Panelists and the audiences discussed women in industry, the female chief executive, how to make the system work for the working woman, jobs for low-income women, women in faith communities, women in the arts, returning to work, volunteering, and women in the military and in sports.[9] Panels on education stressed the need for women’s studies classes, women in teaching and administrative positions, and continuing education for adult women. Workshops on politics urged political action at all levels of government: “A woman’s place is in the House … and Senate.”[10]

Other programs focused on recent changes in women’s private lives: divorce and separation, day care (the congress provided day care for participants), “Occupation Mother: Too Much or Not Enough.” Others reflected the sexual revolution of the 1960s, including birth control, rape, and lesbianism. Because the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973 had legalized abortion under certain circumstances in Roe V. Wade, there were panels on both sides of this controversial issue.[11]

The celebrity speakers also addressed old and new themes. First Lady Betty Ford gave a ringing endorsement of the ERA at the opening session. Congress had passed it in 1972, and it was then circulating around the states for their ratification. Ohio had ratified in 1974, and the amendment needed only four more states to ratify. “While many new opportunities are open to women, too many are available only to the lucky few. Many barriers continue to block the paths of most women, even on the most basic issue of equal pay for equal work. And the contributions of women as wives and mothers continue to be underrated.” She also acknowledged that the amendment aroused “the fears of some – both men and women – about the changes already taking place.” Passage of the ERA was not the solution to all problems, she concluded, but it would be a hopeful start.[12]

Nationally syndicated advice columnist Ann Landers addressed a more personal issue in “A Presentation for Women with Perfect Marriages … and Other Liars.” Women in this feminist era faced special challenges as they sought to reconcile their own identities with their role as wives and mothers, she said. Her advice: no marriage is perfect.[13]

But the congress wasn’t all workshops and lectures. It also showcased local women’s musical talents: the Cleveland Women’s Orchestra, the Sweet Adelines, the Kitchen Band, the St. Adalbert Soul Choir. Comedian Lily Tomlin combined entertainment with pointed political commentary, poking fun at herself, her enthusiastic audience, and thanking congress organizers for giving her Betty Ford’s dressing room.[14] On the final night of the congress, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, husband and wife, gave dramatic readings that linked the past with the present: Davis, an 1857 speech by Frederick Douglass, the revered supporter of equality for women and blacks, and Dee’s own poem, “Calling All Women.”[15]

When it was all over, congress organizers created a laundry list of future goals. Some were old and familiar – “fair representation and participation in the political process”; “equal education and training”; “meaningful work and adequate compensation.” Some addressed specific, contemporary concerns: federal assistance for infant and toddler care, full-day kindergarten, free clinics, more adequate health care insurance, avoiding Medicare cuts, improved health care delivery, crisis shelters for women and children, and altering “societal values so that men do not need to feel superior to women and resort to brute force to prove their masculinity.”[16]

There were some tangible results too. A registry of women’s organization served, like the congress itself, to better connect the widely various women’s groups. Plans for WomenSpace were also finalized, with a grant from the Cleveland Foundation. The new agency set up offices in the YWCA headquarters, providing research, counseling, and programs for women, another continuation of what the congress had done.

THE PUBLIC RESPONSE

The three-day event made the local news for months. Mayor Ralph Perk himself spoke at the opening ceremony. The Cleveland Plain Dealer enthused over the large crowds, thought-provoking workshops, and celebrity speakers. One reader showered praise: “The congress was one of the best organized, most interesting, most innovative events this city has seen in a long time…. [E]veryone working in harmony for a successful conclusion. This is what America should be about…. Pride in Cleveland is still well placed.”[17] The congress did attract national attention. As York proudly stated, “Cleveland became a leader in the struggle for equality for women in equal partnership with men.” It had hosted the biggest IWY celebration anywhere, a feather in the cap of a city still smarting from jokes about the burning of the Cuyahoga River in 1969, a 1973 federal lawsuit against its racially segregated public school system, and the humiliation of having to sell off its sewer system in 1972 and its public transit system in 1975.

Not everyone was happy about the congress, of course. One Cleveland woman wrote in disgust: “When community leaders sponsor workshops on rape, prostitution, abortion and lesbianism for the enlightenment of young people…; when free sex of any variety is promoted as a positive value along with free birth control devices, … when home and family life is denigrated and sex roles blurred, we have the beginning of the end.”[18]

At the other end of the political spectrum, the January 1976 issue of Point of View, habitually critical of almost everything, carried an article by radical feminist Marge Grevatt, entitled “Cleveland’s IWY: Feminism for Sale.” She described the congress planners as “safe” women, naively “co-opted” by “the establishment,” pointing to meetings in the Cleveland Foundation’s “plush headquarters.” She criticized the $300 fee for booths that sold stuff to women, questioning whether the congress was more about serving Higbee’s and Halle’s than about serving Cleveland women. With more justice, Grevatt accused the congress of shortchanging lesbians and lower-income women. Yet even she had some praise for the organizers who worked so hard for no money and with such good intentions. “Some very good things happened,” she conceded: thanks to the workshops and panels and talks and performances, and just coming together in solidarity, Cleveland women woke up. At least to mainstream feminism.[19]

AND THEN WHAT HAPPENED?

Those were heady days – those three days in October 1975. York spoke of the pervasive “atmosphere of joy.”[20] These women may have been joyful, but Grevatt’s criticisms notwithstanding, they weren’t naïve. No one thought the fight for equal partnership had been won, or that a win would be easy.

And sure enough. The social and political ferment of the 1970s gave way to the conservative backlash of the 1980s. Even with a three-year extension, the ERA, the goal most closely identified with 1970s feminism, failed in 1982, just three states short of ratification. Right-to-life organizations picketed abortion clinics and threatened doctors. The Supreme Court imposed restrictions on abortions although Roe V. Wade survived. The Reagan budgets cut funds for social service programs that customarily aided women. The fissures between feminism and traditionalism and between mainstream and radical feminism, apparent in Cleveland in 1975, continued to divide the movement.[21]

But in 2019, it’s important to remember that in the mid-1970s, “feminism” was a dirty word to lots of people and that despite the moderate title of the congress and its mostly modest goals, its planners and participants were not only energetic and optimistic but brave, like the woman’s rights advocates and the suffragists who came before them.

It’s also important to remember that those heady October days in Cleveland were another brave beginning. But not the last.

[1] Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1975: 4.

[2] Examples; http://teachingcleveland.org/roads-less-traveled-clevelands-women-doctors-1852-1984-by-marian-morton/

[3] Marian J. Morton, “How Cleveland Women Got the Vote and What They Did With It,” Teaching Cleveland Stories (Cleveland: Teaching Cleveland, 2013), 106.

[4] Marian J. Morton, Women in Cleveland: An Illustrated History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), 221-222.

[5] CPD, August 5, 1975: 14.

[6] Toward Equal Partnership: Proceedings of the Greater Cleveland Congress, International Women’s Year, 1975 (Cleveland: Greater Cleveland Congress- International Women’s Year, 1976), 29.

[7] Toward Equal Partnership, v.

[8] Morton, Women in Cleveland, 221-222.

[9] Toward Equal Partnership, 47-68.

[10] Toward Equal Partnership, 130.

[11] Toward Equal Partnership, 131-133.-

[12] Toward Equal Partnership, 30-34.

[13] Toward Equal Partnership, 112.

[14] CPD, October 27, 1975: 26.

[15] Toward Equal Partnership, 151-152.

[16] Toward Equal Partnership, 280-282.

[17] CPD, November 1, 1975: 20.

[18] CPD, November 1, 1975: 20.

[19] Marge Grevatt, “ Cleveland’s IWY: Feminism for Sale,” Point of View, January 31, 1976: 1-10.

[20] Towards Equal Partnership, vi.

[21] Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History (New York: McGraw Hill, 2002), 386-393.