The Cleveland School – Watercolor and Clay by William Robinson

From the Canton Museum of Art

The Cleveland School

Watercolor and Clay

Exhibition Essay by William Robinson

Northeast Ohio has produced a remarkable tradition of achievement in watercolor painting and ceramics. The artists who created this tradition are often identified as members of the Cleveland School, but that is only a convenient way of referring to a diverse array of painters and craftsmen who were active in a region that stretches out for hundreds of miles until it begins to collide with the cultural orbit of Toledo, Columbus, and Youngstown. The origins of this “school” are sometimes traced to the formation of the Cleveland Art Club in 1876, but artistic activity in the region predates that notable event. Notable artists were resident in Cleveland by at least the 1840s, supplying the growing shipping and industrial center with portraits, city views, and paintings to decorate domestic interiors.

As the largest city in the region, Cleveland functioned like a magnet, drawing artists from surrounding communities to its art schools, museums, galleries, and thriving commercial art industries. Guy Cowan moved to Cleveland from East Liverpool, a noted center of pottery production, located on Ohio River, just across the Pennsylvania border. Charles Burchfield came from Salem and Viktor Schreckengost from Sebring, both for the purpose of studying at the Cleveland School of Art. To be sure, the flow of talent and ideas moved in multiple directions. Leading painters in Cleveland, such as Henry Keller and Auguste Biehle, established artists’ colonies in rural areas to west and south. William Sommer, although employed as a commercial lithographer in Cleveland, established a studio-home in the Brandywine Valley that drew other modernists to the country. So, while the term “Cleveland School” may not refer to a specific style or a unified movement, it does identify a group of interconnected artists active in a confined geographic region, many of whom who shared common experiences, backgrounds, training, professional challenges, and aesthetic philosophies.

The Cleveland School enjoys a well deserved reputation for achievement in watercolor painting. In May 1942, Grace V. Kelly commented in the Plain Dealer: “Watercolor painting is the special pride of Cleveland and the medium through which its artists are known to connoisseurs throughout the country.” Interest in the medium grew modestly during the nineteenth century, and then accelerated after the founding of the Cleveland Society of Watercolor Painters in 1892. At the time, many people still considered watercolor a form of drawing and inferior to oil painting. After the turn of the century, artists increasingly altered their approach as they began thinking of watercolor, not as tinted drawings, but as an independent form of painting with unique aesthetics and technical issues. The key aspect of watercolor that sets it apart from other painting media is transparent color. Applying thin washes of transparent watercolor over white paper allows light to penetrate the paint layer and reflect off the paper, thereby illuminating the colors with a special radiance. This effect can be enhanced by combining watercolor with areas of opaque gouache and white body color. From a technical standpoint, watercolor is an extremely medium difficult because the liquid paint is quickly absorbed into the paper and dries almost immediately, making it nearly impossible to rework a composition without muddying the colors. Watercolor painters must work swiftly and accurately because there is almost no margin for error.

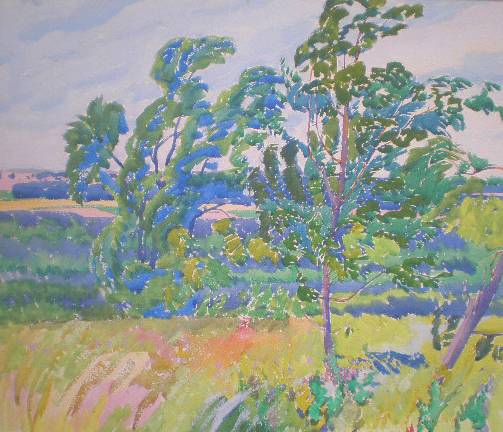

The artists of northeast Ohio developed their own watercolor traditions and raised the medium to such heights that it stands out as an area of special achievement. They learned to exploit the medium’s most distinctive quality—transparency—and to paint quickly and freely, sometimes without preliminary drawing. Ora Coltman (1858-1940) from Shelby, Ohio, was among the early practitioners of the medium. Like other artists of his generation, he found watercolor ideal for making travel sketches and deftly exploited the medium’s inherent transparency to evoke the intensity of sun-drenched, outdoor light. Henry Keller (1869-1949), who taught at the Cleveland School of Art from 1903 to 1945, masterfully employed both transparent and opaque watercolor, also known as gouache. His works range in style from experiments in abstract design, such as Futurist Impression: Factories, to freely rendered views of the Ohio countryside and the beaches of La Jolla, California. A highly influential teacher, Keller introduced a generation of his students and colleagues to modernist principals of abstract design and color theory. He began experimenting with abstract design as early as 1913, the year he exhibited in the Armory Show. Grace Kelly (1877-1950) and Clara Deike (1881-1918) were among the many artists who painted outdoors with Keller at the summer school he established in Berlin Heights, Ohio, in 1909. The large, flat planes of abstract color—especially the intense blue shadows—in Deike’s Sunflowers with Chickens and Kelly’s Cypress are signature features of the modernist style developed by Keller and his colleagues.

Auguste Biehle (1885-1979) and William Sommer (1867-1949), two of the most important and influential pioneers of modernism in Ohio, worked in Cleveland’s commercial art industries. Biehle studied in both Cleveland and Munich. After attending the first exhibition of the German Expressionist group, The Blue Rider, Biehle returned to Cleveland in 1912 and began painting in an avant-garde style that merged abstract color with decorative design. Like many of his Cleveland colleagues, Biehle was a versatile artist who worked masterfully in variety of styles, from modernist abstraction to American scene realism.

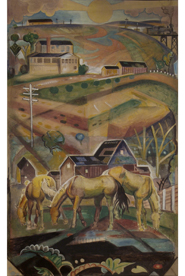

William Sommer deserves special recognition as one of the finest American watercolorist of the twentieth century. Born in Detroit, Sommer came to Cleveland in 1907 to work for the Otis Lithograph Company, where he developed a close relationship with William Zorach (1887-1966). Together, they became leaders in the regional avant-garde movement. In 1911, Sommer helped establish two organizations dedicated to advancing modernist art in Cleveland: the Secessionists and the Kokoon Klub. In 1914, he converted an abandoned school house in the Brandywine Valley, about 20 miles south of Cleveland, into a home and studio that attracted visits from progressive poets and painters, including Hart Crane and Charles Burchfield. Sommer continued painting in a modernist style during the 1920s and 1930s, a period when many artists abandoned abstraction for American scene realism. Sommer’s large watercolor U.S. Mail interprets rural Ohio through the modernist lens of flattened and compressed space, powerfully reductive forms, and inventive color.

Although often described as an isolated, self-taught artist working in the rural hinterlands of America, Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) was an extremely sophisticated painter who learned principles of modernist composition and color theory through Henry Keller, his teacher at the Cleveland School of Art from 1912-1916. Burchfield also discovered avant-garde art by frequenting exhibitions at the Kokoon Klub and by traveling to Brandywine in 1915 to meet “Big Bill Sommer.” It was during this period that Burchfield developed his signature style and ideas about the nature of the creative process. He shared Sommer’s philosophy of using watercolor as a means of externalizing emotions and exploring subconscious fears and dreams by painting quickly and intuitively. Burchfield once explained why he adopted watercolor as his ideal medium: “My preference for watercolor is a natural one . . . whereas I always feel self-conscious when I use oil. I have to stop and think how I am going to apply the paint to canvas [when working in oil], which is a determent to complete freedom of expression . . . To me watercolor is so much more pliable and quick.”

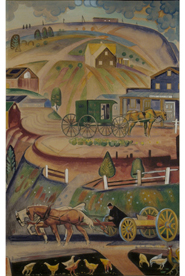

Led by Burchfield, Sommer, Biehle, and their colleagues, a nationally distinguished school of watercolor painting emerged in northeast Ohio during the early years of the twentieth century. They exploited the inherent advantages of watercolor for painting quick, lively views of American scene subjects. Frank Wilcox (1887-1964) developed a masterful à la prima technique for portraying the rural countryside and imagined scenes of Ohio history. William Eastman (1888-1950) depicted the recently constructed Terminal Tower in Cleveland rising against a sunset sky with ominously dark clouds. Clarence Carter (1904-2000) came to Cleveland from Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1923, and developed a national reputation as an imaginative interpreter of American scene subjects, accomplished with a personal blending of realism and modernism.

Carl Gaertner (1898-1952) began haunting the city’s steel mills and factories during the early 1920s and rapidly established himself as a preeminent painter of industrial Ohio, renowned for his dark, moody, deeply expressive winter scenes. Other prominent watercolor paintings of this generation include Lawrence Blazey, Carl Broemel, Charles Campbell, Kae Dorn Cass, Joseph Egan, William Grauer, Joseph Jicha, Earl Neff, Paul Travis, and Roy Bryant Weimer.

Cleveland artists of the next generation continued to develop this regional tradition in watercolor painting. Hughie Lee-Smith, Moses Pearl, Kinely Shogren, and Joseph Solitario were all born after the outbreak of World War I, yet largely followed in the footsteps of their predecessors in using watercolor to record exacting images of life in modern America. One of the most distinguished African-American artists of his time, Lee-Smith came to Cleveland in 1925, took studio classes at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland School of Art, and taught at the Playhouse Settlement (Karamu House) from the 1930s to the early 1940s. His haunting images of lonely and deserted urban settings, sometimes occupied by a few isolated figures, seem symbolic of the alienated condition of African-Americans during a period of pervasive Jim Crow laws, lynchings, a resurgent KKK, and segregation in the military. Solitario recorded memorable images of weary, bored soldiers traveling by train during World War II. Pearl spent a lifetime painting watercolors of Cleveland urban and industrial sites, starting from his teen years in the 1930s to his death in 2003.

Art historians have praised northeast Ohio for its long tradition of excellence in decorative arts and crafts. R. Guy Cowan (1884-1957), a pioneer in the production of fine art ceramics, established studios that attracted leading talents from around the region and served as a center for collaborative production. Born to a family of potters in East Liverpool, Ohio, Cowan settled in Cleveland in 1908 after studying at the New York State School of Clayworking and Ceramics. He founded the Cleveland Pottery and Tile Company in 1913, and later the Cowan Pottery Studios in nearby Lakewood and Rocky River. Cowan’s early works, such as his Lusterware Vase of 1916-17, feature simple yet elegant forms, reflecting the aesthetics of the nineteenth-century Arts & Crafts Movement, accentuated by delicate, monochromatic glazes. Cowan attracted national attention and awards for his ceramics as early as 1917. Critics praised his unique glazes, spectral colors, and high quality materials. During the 1920s, he produced critically acclaimed ceramic figurines in an Art Deco style, as exemplified by Flower Frog with Scarf Dancer of 1925. Adam and Eve of 1928 energizes and unites two figures through decorative rhythms that flow electrically across space.

Cowan began teaching at the Cleveland School of Art in 1928. He used his contracts there to bring leading artists to his studio in Rocky River to collaborate on the production of ceramics, launching a regional renaissance in the medium. Cowan Pottery attained national acclaim prior to its closing in December 1931. Among the notable artists who worked there were: Walter Sinz, Alexander Blazys, Thelma Frazier Winter, Edris Eckhardt, Waylande Gregory, Russell Aitken, and Viktor Schreckengost.

Nationally renowned for his work as a ceramist, industrial designer, painter, and teacher, Schreckengost was born in 1906 to a family of potters in Sebring, Ohio. After attending the Cleveland School of Art from 1924 to 1929, he spent a year studying ceramics at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, and then returned home to find the nation in the midst of the Great Depression, but lucky enough to receive a joint appointment shared between his alma mater and the Cowan Studios. He produced his famous New Yorker or Jazz Bowl at the Cowan Studios in 1931. Commissioned by Eleanor Roosevelt to celebrate his husband’s re-election as governor of New York, the bowl interprets a distinctly American subject—the city at night bursting with the energetic rhythms of jazz—in a lively, Cubist style. Schreckengost noted that the subject was inspired by a night he spent at the Cotton Club listening to Cab Calloway. To suggest a sense of the city at night, Schreckengost employed an innovative sgraffito technique of scratching through a lustrous black upper glaze to expose the deep Egyptian blue below. The bowl was so popular that he created versions in different sizes and glazes. Schreckengost also excelled at incorporating caricature and humor into his ceramics, as seen in his plates devoted to sports, part of an attempt, so he said, to lift the spirits of people devastated by the Depression. The infectious humor of his ceramics seems to have rubbed off on his colleagues at Cowan, who followed the same path of emphasizing light-hearted, whimsical subjects as an antidote to the brutal realities of the era.

After 1945, a new emphasis on geometric abstraction emerged in Schreckengost’s ceramics and watercolors. The same trend appears in the post-war ceramics of other Cleveland School artists, including Claude Conover, Leza Sullivan McVey, and Clement Giorgi. Increasing experimentation with organic forms and delicate glazes also suggests the influence of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s growing collection of Asian art.

Although American artists shifted their focus away from regional schools after the end of World War II, northeast Ohio remained a thriving center of activity in watercolor painting and ceramics. Today, members of the Ohio Watercolor Society come from every corner of the state and actively organize exhibitions that enrich the lives of people in urban and rural communities alike. Northeast Ohio is also dotted with studios, workshops, teaching programs, and societies devoted to ceramics. Museums dedicated to ceramics can be found from East Liverpool to Rocky River. Watercolor painting and ceramics should be celebrated in northeast Ohio, not only as historical artifacts of artistic achievement, but as vital cultural activities that continue to bind the region together.

Image Credits:

“Futuristic Impressions Factory” by Henry Keller, Courtesy of Rachel Davis Fine Arts

Summer Landscape by Grace Kelly, Courtesy of Michael & Lee Goodman

US Mail/Brandywine Landscape by William Sommer, Purchased in Memory of John Hemming Fry, Canton Museum of Art, 2011.18.A.B

“Buildings” by Carl Gaertner`, Courtesy of Rachel Davis

“Jazz Bowl” by Viktor Schreckengost, Courtesy of Thomas W. Darling

“First Nighter” by Edris Eckardt, Courtesy of a private collection

Notes:

[1] According to Mark Bassett, the term “Cleveland School” was first used by Elrick Davis in article published in the Cleveland Press in 1928.

[1] Grace V. Kelly, “May Show’s Watercolors Maintain Usual High Levels Despite Wartime Pressures,” Cleveland Plain Dealer (May 10, 1942), B:12.

[1] “Charles Burchfield Explains,” Art Digest 19 (April 1, 1945), 56.