ohio historical society

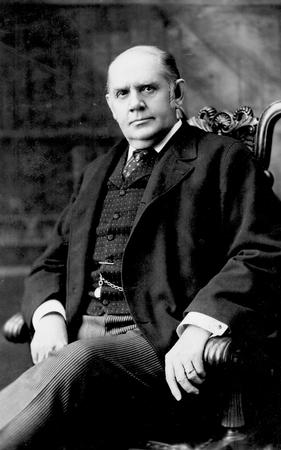

Mark Hanna: The Clevelander Who Made a President

By Joe Frolik

If Marcus Alonzo Hanna, the 19th Century Cleveland entrepreneur who made his fortune in the Gilded Age and then turned his attention, energy and prolific talents for innovation and fundraising to Republican politics, wandered into the Boston campaign headquarters of 2012 GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney, he might feel surprisingly at home with the mechanics of electing a president.

That’s because his fingerprints are all over the way the GOP – or any other political party – spreads its message. But it’s the ideological message of so many modern Republicans that might seem out of date to the man who helped reinvent the party more than a century ago. Hanna, for all of his political and business sophistication, was at heart a pragmatic Midwestern guy who, according to biographer Thomas Beer, served his many guests the finest champagne, but drank water himself. His approach to campaigning ran down the middle of the road because that’s the route he thought led to victory.

And winning, in business or politics, was what mattered to Mark Hanna.

Hanna worked his campaign magic without the aid of computers or the Internet or broadcast media, of course. Yet many of the practices that still define campaigning in the age of social media and micro-targeting were introduced or refined by Hanna during his political tour de force: the 1896 campaign to put William McKinley, his friend and fellow Ohioan, in the White House.

He used polling techniques, albeit primitive ones, to monitor the pulse of the campaign, especially in states he thought could swing either way. He ordered the production of 200 million pamphlets, newspaper inserts and other pieces of literature – at a time when there were barely 14 million voters in the United States. Much of it was issue-oriented and targeted particular market segments such as German-Americans or “colored” voters. He dispatched 1,400 surrogate speakers to spread a unified GOP message, some of them toting new-fangled devices to enthrall audiences with grainy moving pictures of McKinley.

When McKinley turned down Hanna’s suggestion to imitate Democratic rival William Jennings Bryan and take his campaign to the country in person, the resourceful manager arranged to bring the country to McKinley. Between mid-summer and Election Day 1896, some 750,000 people traveled to William and Ida McKinley’s modest home on Market Street in Canton to hear a few words from the former congressman and governor of Ohio. Many came by train, taking advantage of special deep-discount fares that Hanna had negotiated with the railroad barons who shared his antipathy for Bryan’s populism. The pro-Democrat Cleveland Plain Dealer acidly observed that thanks to Hanna’s deal-making with the railroads, going to Canton was “cheaper than staying home.’’

All of this innovation required boatloads of cash, and Hanna excelled at raising it. Before 1896, most presidential campaigns were run through the political parties and relied on tithes from patronage workers. Hanna had broken into politics in Cleveland by raising cash from his fellow businessmen to help elect President James Garfield in 1880, and 16 years later, he took the art of the ask national. He tapped not just the railroaders, but tycoons of every stripe, by stoking their fears of financial catastrophe if Bryan and his “free silver” platform prevailed. The result was a war chest that has been estimated at between $3.5 million and $10 million, in an era when newspapers sold for a penny. One of Hanna’s Cleveland Central High School classmates — a rather successful oilman named John D. Rockefeller – reportedly kicked in $250,000.

But Hanna did more than invent the modern political campaign in 1896 – though give some credit for that to Bryan, too. The Democrat took to “the stump” out of economic necessity, ended up traveling 18,000 miles to give hundreds of speeches and along the way changed American expectations of those who seek the presidency.

Along with the equally pragmatic and more politically savvy McKinley, Hanna basically reinvented the Republican Party. The coalition they forged made the GOP America’s dominant party from 1896 until Wall Street collapsed in 1929. The only Democrat to break the Republican hammerlock on the White House in those years was Woodrow Wilson. He did it twice, the first in 1912 when the GOP split along personality and ideological lines. But even as an incumbent who had kept the U.S. out of the horrific war in Europe, Wilson barely eked out a second term in 1916. When Warren Harding, another Ohio governor, ran for president in 1920, he spoke of returning the country to “normalcy,’’ a response to war, of course, but also an appeal to recall the good times associated with the Republican era ushered in by McKinley and Hanna.

The Ohioans has seen a nation that was being changed by immigration, urbanization and industrialization and sought to invite this new America into the Republican fold. In its own way, that was a pretty radical idea.

For three decades, the GOP had looked backwards. Its leaders played up their ties to Lincoln and Grant and the heroes of the Civil War. They made little effort to attract the newcomers pouring into America’s cities. On one of the great hot-button issues of the age, they often tilted toward the prohibitionists whose movement had a decidedly anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, anti-city undercurrent. Nor did they show much sympathy for the emerging labor movement which was also rooted in America’s fast-growing cities.

McKinley and Hanna set out to change that.

“1896 was the year that McKinley and Hanna tried to redefine the Republican Party,’’ GOP strategist Marshall Wittman told the Washington Post’s David Von Drehle in a 1999 interview. “Instead of rehashing Reconstruction and the Civil War, McKinley offered an appealing image to new immigrants, rising entrepreneurs and working folks.’’

The country was gripped by a ravaging depression as the campaign began, so McKinley hardly needed to demonize the Democrats who controlled the White House (incumbent Grover Cleveland was not seeking a third term). But that wasn’t his nature anyway. McKinley was, like Ronald Reagan, a natural optimist. He billed himself as “an advance agent for prosperity.’’ His central pitch was a call for high tariffs to protect American industries from foreign – which in those days meant European – competition. Strong domestic producers, he argued, would pay better wages and lift all boats.

McKinley and Hanna used that prospect to appeal to urban working class voters. They had little use for divisive, social issues such as immigration, temperance or union bashing. Make no mistake. They were conservatives and very pro-business, especially Hanna who thought government, capitalists and labor should work hand-in hand.

But they were also “Big Tent” Republicans, more interested in who they could bring into the fold than in ideological purity. They sowed the seeds of the center-right Main Street Republicanism that – despite frequent and often bitter internecine battles with harder-edged conservatives – defined the party for most of the 20th Century.

To Hanna, a lifelong friend of the original Rockefeller Republican, that might not sound like cause for celebration.

Hanna had been born in Ohio’s Columbiana County in 1837. His father Leonard was a doctor and his mother Samantha had been a schoolteacher. The Hannas were an entrepreneurial bunch. Leonard and his brothers ran a successful grocery in what’s now the city of Lisbon, and before Mark’s birth, they had invested heavily in a canal they hoped would link the community to the Ohio River. The effort failed, leaving Lisbon economically isolated. Poorer, but undaunted, the Hannas started a grocery business in burgeoning Cleveland, and Leonard moved his family there in 1852.

Mark graduated from Central and enrolled at Western Reserve College, but was soon booted out for bad conduct. He went to work in the family business – the Hannas were expanding from a wholesale grocery to a freight-hauling firm – and never looked back. Because the Hannas were outspoken Republicans and Lincoln supporters, Mark wanted to enlist along with many of his friends when the Civil War began. But his mother, correctly sensing that Leonard Hanna was in declining health – he would die in 1862 — persuaded her oldest not to go. Younger brother Howard enlisted instead. Mark stayed behind to run the business and, according to Beer in his 1929 book “Hanna,’’ to become a one-man entertainment committee whenever friends returned home on leave.

He could afford it because the war was good for the Hannas’ company and for cities such as Cleveland. Factories expanded overnight There was constant, growing demand for food and raw materials from the West. “It was a boom,’’ wrote Beer, “timed to the pulsations of cannons and rifles on the Virginia border.’’ Cleveland’s population grew by 155 percent during the 1860s, and it became a major link between the resources of the Great Lakes and the still-dominant consumer base of the East Coast.

Hanna set aside commerce briefly in 1864 when his National Guard regiment was summoned to active duty to help defend Washington against a rumored Confederate attack. The Perry Light Infantry saw action that July when Gen. Jubal Early drove 10,000 rebels to the outskirts of the capital. Hanna missed the fighting because he was escorting the body of dead soldier back in Ohio. The unit was mustered out of service in August, and a month later, Hanna married Charlotte Augusta Rhodes, the daughter of another Cleveland merchant clan. One big difference between the Rhodes family and the Hannas: Charlotte’s people were ardent Democrats.

Despite that barrier – the way partisanship spills into every walk of life is another element of contemporary American life that Hanna might find familiar– his father-in-law Daniel Rhodes eventually came to admire Hanna’s drive to succeed. Not that everything he touched turned to gold. Right after the war, Hanna bought a refinery and a steamship. In short order, the refinery burned and the ship sank; neither reportedly were insured. Hanna was nearly broke. Biographer Herbert Croly observed that all he had gained during his first decade in business was experience.

That changed dramatically, after Daniel Rhodes invited him into his family’s business in 1867. Hanna the dynamic salesman rushed all around the Great Lakes, using advertising – the copywriter was often Hanna’s brother-in-law, historian James Ford Rhodes — to push its products. Rhodes and Co. prospered, even during difficult economic times in post-war America. Its primary holdings were in steel, iron and coal, and it was through those mining interests that Hanna met William McKinley.

The Panic of 1873 – a global financial crisis triggered by overextended investment banks – hammered the soft coal mines of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Hanna organized many of the mine operators and urged them to meet with the nascent association of miners. Beer reports that Hanna “had no fancy name for his scheme, but he believed in what is now called collective bargaining.’’ Hanna thought strikes were inherently destructive, but he also felt it was foolish for industrialists to pay poor wages and sow discontent. Besides, he believed in his own innate ability to out-bargain workers, customers or anyone else.

By 1876, prices for coal had sunk to a new low. Hanna’s fellow operators slashed wages despite his objections (and refusal to follow suit). The workers then went on strike, also against his advice. One of his partners insisted on bringing in scabs from Cleveland. There was the predictable bloody fight. Ohio Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes – who would wind up in the White House after that fall’s disputed presidential election – dispatched the militia. Shots were fired and a man was killed. Twenty-three miners were arrested for rioting.

Over the objections of his political advisers, McKinley – who in 1871 had been defeated after a single term as Stark County prosecutor, but was eyeing a race for Congress – agreed to defend the miners pro bono. Although some of the strikers initially doubted that this handsome, well-dressed Republican could really be anything but a company spy, he became their savior. Only one miner was convicted. Hanna was not thrilled with the outcome, but he had been thoroughly impressed by McKinley’s skill and integrity.

After the trial, Hanna attended the Republican Convention in Cincinnati that nominated Hayes for president. The future power broker was then little more than an interested observer. He had begun dabbling in politics back home in Cleveland, a pastime that many of his business friends found puzzling. To them, politics was a dirty game to be avoided at all cost. Hanna tried to change their minds, arguing that the conditions in their hometown were as important as their personal fortunes. But he often found himself frustrated by the willingness of local Republican leaders to engage in vote-buying and petty corruption. In 1873, he had even helped a reform-minded Democrat get elected mayor.

It’s worth noting that Hanna did not limit his civic-mindedness to political matters, especially in his adopted hometown. Biographer Herbert Croly reports that in the early 1880s, Hanna was walking along Euclid Avenue, headed for lunch at the Union Club, when a colleague informed him that the Cleveland Opera House was – at that very moment — up for a sheriff’s sale. Hanna excused himself, walked into the theater and joined the bidding. By the time he sat down for lunch, he was $40,000 poorer and the owner of Cleveland’s most luxurious theater.

Hanna brought in new management, insisted on high-quality productions and eventually made the Opera House a profitable enterprise. But Croly writes in “Marcus Alonzo Hanna: His Life and Work,’’ that what Hanna liked most about the Opera House was the performers who worked there. They were energetic big dreamers, larger than life personalities, qualities to which Hanna could relate in business, the arts or politics. Besides, Croly notes, Hanna loved to have a good time.

“Throughout the whole of his life, Mr. Hanna was intensely and inveterately social. His favorite recreation consisted in companionship with other people; and even during his years of closest business preoccupation, he rarely sat down to table without a certain number of guests. On Sundays and holidays, he liked to have the house full. Moreover, he wanted to entertain, not merely his friends and business associates, but (as his mother did before him) prominent and interesting people who visited Cleveland.’’

The wartime entertainment committee had graduated to a bigger stage as his wealth allowed. Good thing, because Hanna’s political endeavors, at least close to home, yielded less cause for celebration.

For all his interest in politics – he even owned the staunchly Republican Cleveland Herald for several years – Hanna never quite mastered the art as practiced in Cleveland. He certainly never controlled the levers of powers here as he would on the national stage. Nor did he play the game as naturally as young Tom L. Johnson did within months of hitting town.

When their paths first crossed in 1879, Hanna owned one of the eight street railway systems that served the city. Johnson – a wunderkind who had run a Louisville railway at age 17, made a fortune by inventing the world’s first coin fare box and then turned a floundering Indianapolis line into a moneymaker – was looking to crack the Cleveland market. According to George E. Condon Sr. in his 1981 book “Cleveland: The Best Kept Secret,” Johnson was just 25 when he bid for a new franchise on the city’s West Side. Hanna pursued it, too. Condon says Johnson proposed the better deal, but that Hanna won on a technicality: the bid specifications included a preference for existing operators.

Johnson refused to stay beaten. He purchased a rail line on what is now West 25th Street. It ended just a few blocks shy of the municipally owned tracks that linked Ohio City to downtown. The final connecting spur was owned by Hanna and his partner Elias Simms. When Johnson asked to use the Hanna-Simms tracks, they told him to get lost. So he hired horse-drawn carriages to ferry his passengers from the terminus of his tracks to the center of downtown. He also launched a public relations campaign against Hanna and Simms. City Council, even though it was generously stocked with their supporters, caved. Hanna and Simms were told to give access to Johnson or lose their franchise.

The rubber match between the two came soon after. Johnson wanted a franchise to build rail lines on the East Side. He envisioned a streetcar network uniting the city and allowing passengers for the first time to go across town for a single fare. Hanna was having none of it. He had ousted Simms from their partnership after the first defeat and had reached out to Johnson, suggesting that they combine forces. Hanna pointed out that he knew the bankers and the pols, while Johnson knew the rail business. Johnson rejected the offer because, he wrote in his autobiography, “We were too much alike.’’ Besides, Cleveland’s future mayor hardly needed Hanna to be his political guide.

When they squared off over Johnson’s bid for an East Side franchise, Hanna appeared at first to have the upper hand, given his deeper roots and his willingness to spread cash to favored officeholders. But Johnson again rallied public support – and he got a little help behind the scenes. Condon says Simms flipped two crucial votes against his estranged partner.

About this time, Beer writes, Hanna was called a “rich busybody” at a meeting of local reformers. Frustrated and maybe a bit embarrassed at being shown up by the new kid in town, Hanna turned his attention to different political stages. He had learned that, as Beer put it, “one might quietly rule in politics without being a politician. One might be an engineer.’’

In 1880, Hanna created a businessman’s club that raised money to cover Garfield’s personal expenses during the presidential campaign and also traveled Ohio raising money for Garfield. The role suited him well. Four years later – after Garfield had been assassinated – Hanna went all out trying to get win the GOP nomination for another Ohioan, Sen. John Sherman. That effort failed, but at the convention, Hanna shared an apartment with McKinley who was chairing the platform committee and being touted as a rising star. Their partnership was cemented four years later, when both were again leading the charge for Sherman.

With the 1888 convention deadlocked, a group of delegates from other states tried to persuade McKinley to seek the nomination. He said no without a moment’s hesitation, reiterating his support for Sherman. That act, by almost all accounts, sealed the deal for Hanna, who admired loyalty above all else. By contrast, Ohio Gov. Joseph Foraker briefly abandoned Sherman in favor of James Blaine. To Hanna, who had been an ally of Foraker until then, that was an act of treachery that could not be forgiven. The two remained at odds until Hanna died.

Finally in 1896, it was McKinley’s turn. Hanna — who had largely set aside his vast business interests in what had become the M.A. Hanna Co. to devote himself to this race – left no stone unturned to help his friend succeed. Ironically perhaps, his devotion became one of the big issues in the campaign and for many years after, a burden on McKinley’s political legacy.

Bryan’s populism scared off many usually Democratic editors, but not William Randolph Hearst, whose silver mines would skyrocket in value if “bimetalism” prevailed. Hearst realized that to elevate Bryan, he had to bring down McKinley. That was no easy task given the Ohioan’s squeaky-clean reputation. But Hearst and his papers saw in Hanna the perfect surrogate target.

Cartoonist Homer Davenport famously depicted Hanna as “Dollar Mark,’’ a bloated character dressed in a suit covered with dollar signs. McKinley was drawn much smaller, as almost a child – or a puppet – under the sway of Hanna. Others depicted him – resurrecting a moniker coined by Edwin Cowles, a Republican rival in Cleveland during the 1880s when they owned competing newspapers – as a gluttonous Roman nobleman: Marcus Aurelius Hanna.

Hearst’s editorials hit relentlessly at an incident that supposedly proved McKinley was beholden to Hanna and other oligarchs: During the Panic of 1893, McKinley was presented with a bill for $100,000 to cover bad loans he had co-signed for a friend in Youngstown. Lacking anything near that kind of cash, McKinley planned to resign as governor and return to his law practice to pay the debt. When he informed Hanna, the Clevelander would have none of it. He quickly assembled a group of wealthy friends who retired the notes. McKinley and his wife put property in a trust to repay their benefactors, but no claims were ever filed.

The attacks did not prevent McKinley from winning in 1896. Although some Republicans panicked when Bryan appeared to be riding a wave of popular support after his “Cross of Gold’’ speech at the Democratic Convention, McKinley and Hanna did not. They both insisted that “silver fever’’ would run its course before November, and they were right.

For almost a century, McKinley was chronically underappreciated by historians. That’s partly because his successor, the dynamic Theodore Roosevelt, would have overshadowed almost anyone. But Hanna’s role also helped diminish McKinley. Many scholars accepted the premise that it was Hanna who pulled the strings in their relationship, Hanna who ran the campaign, Hanna who told the candidate – and later the president — what to say.

More recent accounts suggest that the two were actually a complementary pair. That Hanna by 1896 understood the mechanics of campaigning better than anyone ever had. That McKinley understood the American people, the issues of the day and the interpersonal dynamics of politics better than any of his political peers. Together they reinvented the Republican Party as a more inclusive, future-oriented coalition that looked like what America was becoming. Beer, as far back as the 1920s, insisted that Hanna, against all stereotypes, had actually been the junior partner in this endeavor, and that his affection for McKinley was so genuine that he would do whatever he thought his friend needed.

Not that the relationship was a one-way street. Once McKinley was in the White House, he helped Hanna fulfill a longtime ambition by naming the aging Sherman as secretary of state. That opened up a Senate seat from Ohio to which Gov. Ada Bushnell, reportedly under pressure from McKinley, quickly appointed Hanna. A year later, he was re-elected by the legislature – senators weren’t chosen by the vote of the people until after 17th Amendment was ratified in 1913 – after a bitter contest at the Statehouse that reignited the animosity between Foraker and Hanna. The allegations of vote-buying, arm-twisting and even kidnapping that swirled in Columbus during and after that contest only reinforced Hanna’s negative image as a ruthless political boss.

Once in Washington, Hanna remained close with McKinley. He reportedly turned down an invitation to reside in the White House while he searched for a place to live and eventually took a hotel suite near the executive mansion. When Vice President Hobart died in 1899, Hanna took over the lease on his house, just across Lafayette Square from the White House. After some back and forth about his role in the 1900 campaign – by some accounts, McKinley delayed asking Hanna to serve as manager again in order to show the public who was boss in their relationship – he ultimately led the re-election effort. This time, there was little doubt about the outcome. The theme of the re-election campaign, Hanna said, was simple: Leave well enough alone. The voters did and McKinley won easily.

It was his fellow Republicans who gave Hanna more cause for worry that year. The GOP bosses of New York state saw the vice presidential vacancy as an opportunity to rid themselves of Gov. Theodore Roosevelt, the Spanish-American War hero they despised. Hanna had opposed the war and defended McKinley’s reluctance to enter the conflict until the destruction of the battleship Maine made their position politically tenable. He distrusted Roosevelt and others he felt had been too keen to fight. The feeling was mutual. Roosevelt had famously observed of the 1896 campaign that Hanna sold McKinley “like a patent medicine.”

But when McKinley opted to let the convention to pick his running mate, the New Yorkers prevailed. Hanna, for once, had been caught off guard. He urged McKinley, by phone, to let him use patronage to shake loose enough delegates to derail Roosevelt. The president said no. Hanna reportedly lamented to other GOP heavyweights that his friend was making a terrible mistake: “Don’t any of you realize that there’s only one life between that madman and the White House?” Upon returning to Washington, Hanna wrote a note to McKinley informing him that, “Your duty to the country is to live for four years from next March.’‘

McKinley did not. In September 1901, he was shot by an anarchist at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. His death devastated Hanna, personally and politically. And yet, to the surprise of many, he eventually built a working relationship with Roosevelt. It was Hanna who led the Senate fight to build the trans-ocean canal in Panama rather than elsewhere in Central America. And he devoted much time to his role as first president of the National Civic Federation, a reform effort that included the likes of Andrew Carnegie and Samuel Gompers. The organization sought to broker labor peace by taking disputes to mediation (Hanna had headed off a potentially incendiary coal strike just before the 1900 election) and lobbied for the passage of child labor laws and workers compensation programs.

Despite their truce, Hanna considered challenging Roosevelt for the 1904 nomination. Maybe he couldn’t get over his earlier animosity toward “that damn cowboy.’’ Maybe he wanted to show the world that he could win the big prize without McKinley But in a maneuver that would have made Tom L. Johnson proud, Roosevelt pulled a fast one on Hanna.

Working in tandem with Hanna’s old nemesis Foraker, the president arranged for a resolution supporting his reelection to be introduced at the 1903 Ohio GOP convention. Hanna was in a bind, just as TR and Foraker had hoped. If he voted for the resolution, he would effectively end his own campaign before it started. If he opposed it, he would invite the president’s wrath before he had any organization in place. When Hanna told Roosevelt that he might oppose the resolution as premature, the president assured him that he was not requesting anyone’s support. Then he twisted the knife, adding that, of course, he knew all loyal backers of his administration would surely support such a resolution anyway.

Hanna was check-mated. He voted with Foraker and for Roosevelt. Not that it mattered. There would be no insurgency. On Feb. 15, 1904, Hanna died of typhoid fever and was buried in Lakeview Cemetery.

He had made a fortune – the M.A. Hanna Co. lives on today as PolyOne – elected a president and helped create a political coalition that dominated American politics for more than three decades. Not too shabby for a kid from Cleveland.

For more on Mark Hanna, go here