These articles are based on this 2011 Master’s Degree Thesis written by John Baden. The thesis is here (4.3mg pdf download)

RESIDUAL NEIGHBORS JEWISH-AFRICAN AMERICAN INTERACTIONS IN CLEVELAND FROM 1900 to 1970

Part 1

Getting by Together: African American-Jewish Interactions in Cleveland 1900-1938

by John Baden

Although there are many excellent works of Cleveland history, they tend to portray its ethnic groups in isolation from one another; as do Cleveland’s numerous ethnic events and landmarks. Despite widespread racism and segregation, though, ethnic groups often interacted with and relied on each other. This essay examines some of the once widespread interactions between African Americans and Jews in Cleveland proper between 1900 and 1938. While some interactions between African Americans and Jews were deliberate (especially partnerships created to combat racism), most were unintentional products of daily life. Yet, as we will see, historical forces profoundly shaped even the most mundane interactions like going to the store.

Large-scale African American – Jewish interactions began in the early nineteenth century. Prior to this time, African Americans and Jews had miniscule populations in the city. Jews, on the other hand entered Cleveland in large numbers during the late eighteenth century and twentieth century. By 1910, there were 60,000 Jews in Cleveland and only 8,448 African Americans.[1] On the eve of World War I (1910-14), most of the city’s African Americans and Jews congregated around Central Avenue, which is located just east of downtown. The neighborhood that bears this avenue’s name, Central, was a diverse and integrated urban community. Apart from being home to the largest number of Jews and African Americans, it was also home to Big Italy and other ethnic groups as well.[2] Thus, residents needed to interact with each other at neighborhood institutions like grocery stores for sustenance.

Figure 1 A mapquest.com map of Cleveland’s Central neighborhood.

Each migrant brought with them the talents and trades they acquired in their previous home. The capital and social status each person brought with them to the neighborhood often influenced their interactions with others. Some of these trades like small-scale store managing transferred well to life in urban Cleveland. Others, like agriculture or mining were much harder to convert into a viable trade in such a dense urban environment. Anti-Semitic laws made it rare for Jews to engage in agricultural work in Europe, while African Americans had been forced to perform it for several centuries. Although most Jews were not wealthy, a few brought significant wealth with them to the country, and invested in community programs like the Hebrew Free Loan Association. These all gave Jews a number of assets that allowed many of them to transition into life in Cleveland more successfully than many other groups. Before long, many Jews had found success in the retail and the garment industry. African Americans, on the other hand, had few of these advantages, and faced even more discrimination, which shackled social mobility for most. Despite these differences, African Americans and Jews often lived in the same neighborhoods for much of the early twentieth century.

Because of the aforementioned advantages many Jews had, African American – Jewish relations often unfolded as client-patron relationships. African Americans often relied on Jewish leaders for commercial goods, credit, jobs, political patronage, and “protection” in the underground economy. Many Jews in Cleveland, in turn, relied on African American customers and employees at their establishments for their livelihoods.

World War I was a turning point for African American-Jewish interactions. The war caused great labor shortages, and factory owners began employing African Americans. After this, thousands of Southern African Americans left their homes for new ones in Cleveland’s Central neighborhood. Consequently for African American – Jewish relations, African Americans entered Central in large numbers at the very time (roughly 1914-1925) most Jews were leaving.[3] Most Jews had lived there for some time, and were now able to move on to better neighborhoods by the 1920s. Their residences were then occupied by African American migrants from the South who became the area’s new residents, and customers.[4] Many Jews who left Central, however, held on to assets and businesses that they operated in their old neighborhood. This included many grocery stores, shops, and property. For example, 62-73 percent of grocers on Central Avenue were still Jewish in 1920, and 45.5 to 58 percent in 1930, after most Jews had left the neighborhood.[5] Prejudice from white society in general made it very difficult for African Americans to open competitive institutions. As a result, African Americans continued to use Jewish-owned services in the neighborhood, ensuring such businesses would be profitable for decades after most Jews had moved out.

Selling conditions in segregated communities were not consumer friendly. Unfortunately, prices were often high for the quality of goods or property rendered. For instance housing prices were high, largely because non-Jewish whites had shut African Americans out of most of the city’s housing market, and refused loans to African Americans. Therefore, supply was short for commodities and services in high demand. Like nearly everyone who owned property or stores, most people in Central probably sold for the highest price they could. It was a coincidence of history and socioeconomic factors, that Jews owned much of Central’s businesses and property, and were disproportionately selling to African Americans. In effect, Jewish business and property owners often became middlemen between African Americans and white Christian society.[6]

Patron-client relationships between Jews and African Americans also developed in the spheres of politics and organized crime. Until African Americans had enough voters to elect their own councilmen, Republican political boss Maurice Maschke (who was Jewish) developed a patronage partnership with several notable African Americans. Maschke allied with vice-king Albert “Starlight” Boyd, an African American, to deliver black votes to the Republican Party in exchange for modest patronage and other favors. Maschke also supported African American Thomas W. Fleming’s successful bids for city council and allowed Fleming to dispense a modest amount of patronage into the black community. In turn, Maschke played a role as an advocate for the Republican Party to take a stronger civil rights stand, and played a role in the appointment of Fleming’s wife, Lethia to the Republican National Executive Committee and Colored Women’s Bureau of the Republican National Committee.[7]

The client-patron relationship between African Americans and Jews also extended to organized crime. Aspiring criminals in Central had to either push out existing crime networks or become their clients. One of the most contested under-ground niches during the 1930s was the “numbers “racket in Central’s African American economy. Somewhat mirroring the Maschke-Boyd relationship mentioned above, Jewish American crime boss Shondor Birns helped bring African American numbers runners and prostitution workers under his patronage. At this time, Birns represented the Cleveland mafia which was a product of a merger between the local Jewish criminal syndicate and local Italian mafia. Around 1932, Birns helped secure an agreement where the Cleveland mafia would no longer harass African American numbers runners and secure police protection for them in exchange for a forty percent take in gambling operations and three dollars a week from each prostitute.[8][9] This arrangement appears to have lasted until the 1950s.

These examples in the underworld demonstrate that many African Americans who interacted with one another often did so for self-interest. Most were likely making the most of a situation that prejudice had dealt them. Shondor Birns, for example, grew up as an impoverished orphan, and in many ways was a victim of the generations of anti-Semitism that wrecked devastating poverty on many Jews. In the United States, though, lighter skin tone and a measure of social acceptance allowed many Jewish-Americans to earn a living by rendering services to an ethnic group more marginalized than themselves. Similarly, African American gangsters did not necessarily “choose” to be Birns’s clients. The existing mafia, however, had too many weapons, political alliances, and connections with drug suppliers for African Americans to compete. Therefore, African Americans gangsters became clients of “off-white” patrons in order to scratch out a living in a racist society. As had been the case in commercial and political spheres, Jews often served as “middlemen” between white society and the marginalized African American community.[10]

Although the patron-client relationship that developed in Cleveland and other cities throughout the North helped many African Americans with services, some grew resentful of their predicament. Racism continued to severely limit most African Americans’ opportunity, and most likely believed they would no longer need “middlemen” if racism ended. Evidence suggests that most of these critics acknowledged Jews had not created the situation, but resented that the profits made from such arrangements.[11]

Cleveland’s African American newspaper, The Call & Post, offered complaints about relying on non-African American businesses throughout the 1930s. One article for example complained that the lack of African American businesses in Cleveland meant that African Americans would receive little benefit from the upcoming nation Elks Lodge convention. The columnist stated, “the Jew…in his typical way will foresee the coming of the Elk money and start planning for them…while the colored man will sit by watching him.” Thus, African Americans needed to “open up a decent colored night club where we and the Elks can go so we can stop patronizing the Jew who in reality want us but only our money so that he can build himself a fine home on the heights and then not permit you to live next to him but only work in the kitchen.”[12]

Despite these anti-Semitic comments, the article resulted in more ambiguity than hostility. The following week, the columnist apologized. He wrote that many people were “rightly” offended by his column and that he should have used the word “white” rather than “Jew” which “singled out the race that is closer and more able to understand the Negro.”[13] A columnist had expressed anti-Semitic remarks out of frustration, but presumably African Americans readers had demanded a retraction. Despite calls like this to patronize “their own” establishments, Jewish-owned establishments proved just as popular among African American customers, even when they directly competed.[14] Some African Americans who worked in Jewish-owned establishments also gained valuable skills. Future Congressman Louis Stokes, an African American, was among those grateful for his experience at one such store during the early 1940s. In an interview with Teaching Cleveland, he even recalled his employer escorting a potential customer out of the store who refused service from Stokes.[15]

During the 1930s, activists formed campaigns throughout the Northern United States urging African Americans, “don’t shop where you can’t work.” These campaigns encouraged African Americans to not shop in establishments that did not hire African American employees. Since Jewish Americans owned many of the businesses in African Americans communities, they were often the targets of these protests and boycotts.

Cleveland’s “don’t buy where you can’t work” campaign was organized by the Future Outlook League, and headed by activist John Holly and The Cleveland Call & Post (Cleveland’s black newspaper) editor William O. Walker. The Future Outlook League’s leadership appears to have recognized many of the businesses they targeted were Jewish owned, and did not want their organization engaging anti-Semitism. For instance, a 1938 article of the league’s newspaper, The Voice of the League stated, “Don’t spend your money where you can’t work. And don’t let your boycott against local merchants lead you into an anti-Semitic campaign. Do not curry favor with anyone by showing them how much you hate the Jews or anyone else.”[16]

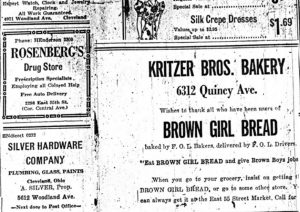

The Future Outlook League also sought to encourage African Americans to patron stores that hired black employees. Many of these businesses appear to have been Jewish-owned. For instance, an article from the The Voice of the League urged people to “pay Stall No. 32 [at the Woodland E. 5th St. Market] a visit when you do your shopping this Saturday,” because its owners, Mr. Baumeister and Mr. Schmiedl, “kept a black butcher on the job with full pay after he broke an arm.[17] Businesses such as Rosenberg’s Drug Store, Hoicowitz Dept. Store, Cohen’s Southern Food Store, and Kritzer Bros Bakery also advertised their business’ hiring practices in the Voice of the League as an inducement to patronize their business.[18] Thus, African Americans were able to engage in criticism of some local establishments that may have happened to be Jewish, but appear to have restricted such criticism to these businesses, and not Jewish store owners in general.

Figure 7 Some advertisements found in the Voice of the League telling readers that they hire African Americans. These advertisements appeared on the same pages, but were spliced together for the benefit of the reader[19]

The 1930s and 1940s, of course, was a tumultuous time period for African Americans and Jews. Anti-Semitism was growing to new levels in Hitler’s Germany, and Jewish immigration to the United States had virtually been shut off since 1921. Paradoxically, however, many Jewish Americans were finding some measure of success in the United States, despite the hardships of the Great Depression. This made it difficult for many African Americans to understand why many Americans were so condemning of Hitler’s anti-Semitism during the Nuremberg Law era, when African Americans faced similar restrictions in the United States.

Many Call & Post articles mentioned this irony. For instance, a 1935 article reported that Hitler had deflected criticism of his persecution of the Jews by telling Americans to “tend to your own lynchings of Negroes.”[20] The article ended by reminding readers that the United States had still failed to pass an anti-lynching bill, and that “America has a lot of housecleaning to do before she can start finding fault with other nations.”[21] Thus, it appears that many African Americans felt a degree of racism at play when white Americans decried the situation in Germany, but made little effort to improve African Americans lives in their own country.

Another Call & Post column in 1938 took some Cleveland Jewish business owners to task for discriminating against African Americans, while Jews faced similar persecution in the Europe. In this article, a fictional street-talking African American stated that “Mose could feel sorrier and could cry louder and longer [for German Jews] if’n he hadn’t experienced der same treatment from der same Jewish race.”[22]

Despite this column, most articles about Jewish persecution appear to have ceased to note alleged hypocrisy by late 1938. That November, German authorities had forced some 25 to 30,000 Jews into concentration camps, destroyed thousands of businesses, and burned over two-hundred synagogues during Kristallnacht. These events appear to have convinced many Call & Post writers that something unique was happening to Jews in Germany. After these events, nearly every article appears to have portrayed Jews as allies against racism, and perhaps sought an opportunity to link American sympathy for German Jews with African Americans’ freedom struggle in the United States.[23] For example, Call & Post articles entitled, “Anti-Semitism, A Weapon of the Lynch Lords,” “Racial Persecution is Contagious,” “Negroes are Not Opposing Haven for German Jews,” “The Plight of the Jews,” expressed both sympathy for persecuted Jews, and the hopes that the two communities could unite against racism.[24] As a Call and Post article entitled, “The Negro and the Jew, Partners in Distress” saw it, “This partnership [Jews and blacks] in distress inevitably brings about a fellow feeling between these two persecuted races. The writer continued, “The Negro is in a large measure the beneficiary of Hebrew persecution,” and that “the vial of wrath which was poured out upon the head of the Negro alone, is now spread out so as to cover the Jews as well.”[25] The article concluded by saying that their partnership will triumph over evil, and Christianity and democracy over irreligion and dictatorship. A somewhat awkward if not ambiguous hope, given that an article calling for increased cooperation between African Americans and Jews concluded by heralding the inevitable triumph of Christianity.

Similar conclusions were reached by African Americans and Jewish leaders throughout the country. Indeed, after World War II, Jews and African American leaders would form a civil rights alliance that would go on to dismantle most the nation’s de jure racism, and transform the nation. Yet, ironically, relations between most African Americans and Jews changed little through the 1930s and 40s. Gentile white prejudice against African Americans continued to cripple most African Americans’ ambitions to enter the middle class. As a result, Jews in cities like Cleveland would continue to serve as patrons or middle-men of sorts to African Americans for decades to come. As we will see in the next segment, though, this relationship would be heavily altered if not jettisoned altogether during the civil rights era.

[1] Judah Rubinstein and Jane Avner, Merging traditions: Jewish life in Cleveland (Kent: Kent State University Press, 2004), 29. Kenneth L. Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870-1930 (University of Illinois Press, 1978), 10.

[2] Gene P. Veronesi, Italian Americans and their communities of Cleveland (Cleveland State University, 1977).http://www.clevelandmemory.org/italians/Partiii.html

[3] Levy, Donald, A Report on the Location of Ethnic Groups in Greater Cleveland, (The Institute of Urban Studies, 1972), 24.

[4] For the purposes of this essay, Jews will be referred to as whites, as this was their legal classification. Although a case has been made by many scholars that Jews were not perceived as entirely white, or white at all, this issue is beyond the scope of this paper.

[5] John Baden, “Residual Neighbors: Jewish-African American Interaction in Cleveland from 1900 to 1970” (master’s thesis, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, 2010), 23

[6] The term “middlemen” is taken from the Middleman minority theory. For an overview of this, see Pyong Gap Min, Caught in the Middle: Korean Merchants in America’s Multiethnic Cities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 21-22.

[7] Randolph C. Downes, “Negro Rights and White Backlash in the Campaign of 1920,” ” Ohio History, 88, vol. 75 (Winter 1966) , http://publications.ohiohistory.org/ohstemplate.cfm?action=detail&Page=007588.html&StartPage=85&EndPage=107&volume=75&newtitle=Volume%2075%20Page%2085.

[8] Daniel R Kerr, “’The Reign of Wickedness’: The Changing Structures of Prostitution, Gambling and Political Protection in Cleveland from the Progressive Era to the Great Depression,” 1998, (M.A. Thesis, Case Western Reserve University, 1998), 45.

[9] (Kerr 1998, 45-47) Services were paid for “protection” from authorities, but often meant protection from their gang attacking the numbers operators.

[10] For a discussion of “middle man theory,” see Pyong Gap Min, Caught in the Middle: Korean Communities in the New York and Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). A more in depth discussion of Jewish-African American relations in the underground economy can be found in Baden, “Residual Neighbors: Jewish-African American Interaction in Cleveland from 1900 to 1970.”

[11] For a fuller discussion of this, see Baden, 29-45. Once notable essay expressing these views is James Baldwin, “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White (1967).” in Paul Berman, Blacks and Jews: Alliances and Arguments (New York: Delacorte Press, 1994), 31-41.

[12] T.D.S., “ON THE AVENUE:DAMON TURNS SPEED DEMON,” Cleveland Call and Post, April 8, 1937, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009).

[13] T.D.S., “ON THE AVENUE: MY APOLOGIES,” Cleveland Call and Post, April 15, 1937, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009).

[14] “ON THE AVENUE:WITH TDS NITECLUB LULLABY,” Cleveland Call and Post, April 30, 1936, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009). A good discussion on African American customers and Jewish businesses in Chicago can be found in St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, “The Growth of a ‘Negro Market,’” in Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States, ed. Maurianne Adams and John H. Bracey (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 358-60.

[15]“Part 2: Interview with Louis Stokes Former Congressman (1969-1999),” Teaching Cleveland Digital at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage video, 15:31, March 24, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7MYAocKZM8.

[16] J.M. Dowden, “Boycotts,” The Voice of the League, July 16, 1938.

[17] “untitled article,” The Voice of the League, July 16, 1938.

[18] The Voice of the League, March 2, 1936 and January 27, 1940.

[19] The Voice of the League, date unknown.

[20] “THE NAZIS POKE FUN AT AMERICA,” Cleveland Call and Post, August 22, 1935, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009).

[21] (Ibid.)

[22] “MOSE of the ROARING THIRD: MOSE WEEPS.” Cleveland Call and Post, December 8, 1938, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed March 15, 2010).

[23] Kelly Miller, “The Negro And The Jew, Partners in Distress,” Cleveland Call and Post, November 17, 1938, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed March 21, 2010).

[24]Proquest searches of historical Call & Post articles, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed March 21, 2010)

[25] Kelly Miller, “The Negro And The Jew, Partners in Distress,” Cleveland Call and Post, November 17, 1938, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed March 21, 2010).