Garrett Morgan’s long road to inventing the modern-day traffic light

by Alanna Marshall

The link is here

www.teachingcleveland.org

Garrett Morgan’s long road to inventing the modern-day traffic light

by Alanna Marshall

The link is here

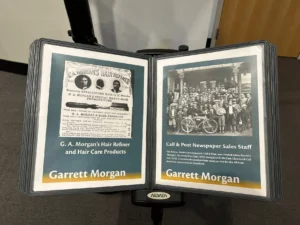

John Patterson Green, father of Labor Day in Ohio, and his enduring legacy -Cleveland.com Sept 1, 2014

Here is link to Rep. Green’s autobiography, “Fact Stranger Than Fiction”

THE BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENT AND COMMUNITY PLANNING IN URBAN PARKS IN CLEVELAND, OHIO, 1945-1977

BY STEPHANIE L. SEAWELL

Univ of IL 2014

The link is here

If that link does not work, try this

Lecture delivered in 1983 by Kenneth Kusmer from Temple University. Part of the Cleveland Heritage Program

Written by Kenneth L. Kusmer

AFRICAN AMERICANS. Cleveland’s African American community is almost as old as the city itself. GEORGE PEAKE, the first black settler, arrived in 1809 and by 1860 there were 799 blacks living in a growing community of over 43,000. As early as the 1850s, most of Cleveland’s African American population lived on the east side. But black and white families were usually interspersed; until the beginning of the 20th century, nothing resembling a black ghetto existed in the city. Throughout most of the 19th century, the social and economic status of African Americans in Cleveland was superior to that in other northern communities. By the late 1840s, the public schools were integrated and segregation in theaters, restaurants, and hotels was infrequent. Interracial violence seldom occurred. Black Clevelanders suffered less occupational discrimination than elsewhere. Although many were forced to work as unskilled laborers or domestic servants, almost one third were skilled workers, and a significant number accumulated substantial wealth. Alfred Greenbrier became widely known for raising horses and cattle, and MADISON TILLEY employed 100 men in his excavating business. JOHN BROWN, a barber, became the city’s wealthiest Negro through investment in real estate, valued at $40,000 at his death in 1869. Founded by New Englanders who favored reform, Cleveland was a center of abolitionism before the CIVIL WAR, and the city’s white leadership remained sympathetic to civil rights during the decade following the war. Black leaders were not complacent, however. Individuals such as Brown and JOHN MALVIN often assisted escaped slaves, and by the end of the Civil War a number of black Clevelanders had served in BLACK MILITARY UNITS in the Union Army. African American leaders fought for integration rather than the development of separate black institutions in the 19th century. The city’s first permanent African American newspaper, the CLEVELAND GAZETTE, did not appear until 1883. Even local black churches developed more slowly than elsewhere. ST. JOHN’S AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL (AME) CHURCH was founded in 1830, but it was not until 1864 that a second black church, MT. ZION CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH, came into existence.

Between 1890-1915, the beginnings of mass migration from the South increased Cleveland’s black population substantially (seeIMMIGRATION AND MIGRATION). By World War I, about 10,000 blacks lived in the city. Most of these newcomers settled in the Central Ave. district between the CUYAHOGA RIVER and E. 40th St. At this time, the lower Central area also housed many poor immigrant Italians and Jews (see JEWS & JUDAISM). Nevertheless, the African American population became much, more concentrated. In other ways, too, conditions deteriorated for black Clevelanders. Although black students were not segregated in separate public schools or classrooms (seeCLEVELAND PUBLIC SCHOOLS), as they often were in other cities, exclusion of blacks from restaurants and theaters became commonplace, and by 1915 the city’s YOUNG WOMEN’S CHRISTIAN ASSN. (YWCA) prohibited African American membership.HOSPITALS & HEALTH PLANNING excluded black doctors and segregated black patients in separate wards. The most serious discrimination occurred in the economic arena. Between 1870-1915, Cleveland became a major manufacturing center, but few blacks were able to participate in INDUSTRY. Blacks were not hired to work in the steel mills and foundries that became the mainstay of the city’s economy. The prejudice of employers was often matched by that of trade unions (see LABOR), which usually excluded African Americans. As a result, by 1910 only about 10% of local black men worked in skilled trades, while the number of service employees doubled.

Increasing discrimination forced black Clevelanders upon their own resources. The growth of black churches was the clearest example (seeRELIGION). Three new churches were founded between 1865-90, a dozen more during the next 25 years. Baptists increased most rapidly, and by 1915 ANTIOCH BAPTIST CHURCH had emerged as the largest black church in the city. Black fraternal orders also multiplied, and in 1896 the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People was established (see ELIZA BRYANT VILLAGE). With assistance from white philanthropists (see PHILANTHROPY), JANE EDNA HUNTER established the PHILLIS WHEATLEY ASSOCIATION, a residential, job-training, and recreation center for black girls, in 1911. Blacks gained the right to vote in Ohio in 1870, and until the 1930s they usually voted Republican. The first black Clevelander to hold political office was JOHN PATTERSON GREEN, elected justice of the peace in 1873. He served in the state legislature in the 1880s and in 1891 became the first African American in the North to be elected to the state senate. After 1900 increasing racial prejudice made it difficult for blacks to win election to the state legislature, and a new group of black politicians began to build a political base in the Central Ave. area. In 1915 THOMAS W. FLEMING became the first African American to win election toCLEVELAND CITY COUNCIL.

The period from 1915-30 was one of both adversity and progress for black Clevelanders. Industrial demands and a decline in immigration from abroad during World War I created an opportunity for black labor, and hundreds of thousands of black migrants came north after 1916. By 1930 there were 72,000, African Americans in Cleveland. The Central Ave. ghetto consolidated and expanded eastward, as whites moved to outlying sections of the city and rural areas that would later become SUBURBS. Increasing discrimination and violence against blacks kept even middle-class African Americans within the Central-Woodland area. At the same time, discrimination in public accommodations increased. Restaurants overcharged blacks or refused them service; theaters excluded blacks or segregated them in the balcony; amusement parks such as EUCLID BEACH PARK were usually for whites only. Discrimination even began to affect the public schools. The growth of the ghetto had created some segregated schools, but a new policy of allowing white students to transfer out of predominantly black schools increased segregation. In the 1920s and 1930s, school administrators often altered the curriculums of ghetto schools from liberal arts to manual training. Nevertheless, migrants continued to pour into the city in the 1920s to obtain newly available industrial jobs. Most of these jobs were in unskilled factory labor, but some blacks also moved into semi-skilled and skilled positions. The rapid growth in the city’s black population also created new opportunities in BALDWIN RESERVOIR and the professions. Most black businesses, however, remained small: food stores, restaurants, and small retail stores predominated. Two successful black-owned funeral homes opened early in the century, the HOUSE OF WILLS (1904), founded as Gee & Wills by J. WALTER WILLS, SR., and E. F. Boyd Funeral Home (1906), founded by ELMER F. BOYD and Lewis Dean. Although the employment picture for blacks had improved, serious discrimination still existed in the 1920s, especially in clerical work and the unionized skilled trades.

Black leadership underwent a fundamental shift after World War I. Prior to the war, Cleveland’s most prominent blacks had been integrationists who not only fought discrimination but also objected to blacks’ creating their own secular institutions. After the war, a new elite, led by Fleming, Hunter, and businessman HERBERT CHAUNCEY, gained ascendancy. This group did not favor agitation for civil rights; they accepted the necessity of separate black institutions and favored the development of a “group economy” based on the existence of the ghetto. By the mid-1920s, however, a younger African American group was beginning to emerge. “New Negro” leaders such as lawyer HARRY E. DAVIS and physician CHARLES GARVIN tried to transcend the factionalism that had divided black leaders in the past. They believed in race pride and racial solidarity, but not at the expense of equal rights for black Clevelanders. The postwar era also brought changes to local institutions. The influx of migrants caused problems that black, churches were only partly able to deal with. The Negro Welfare Assn., founded in 1917 as an affiliate of the National Urban League (see URBAN LEAGUE OF GREATER CLEVELAND), helped newcomers find jobs and housing. The Phillis Wheatley Assn. expanded: a fundraising drive among white philanthropists made possible the construction of its 9-story building in 1928. The Cleveland branch of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP, est. 1912), led by “New Negroes,” expanded, with 1,600 members by 1922. The NAACP fought the rising tide of racism in the city by bringing suits against restaurants and theaters that excluded blacks, or intervening behind the scenes to get white businessmen to end discriminatory practices. The FUTURE OUTLOOK LEAGUE, founded by JOHN O. HOLLY in 1935, became the first local black organization to successfully utilize the boycott.

The Depression temporarily reversed much of this progress. Although both races were devastated by the economic collapse, African Americans suffered much higher rates of unemployment at an earlier stage; many black businesses went bankrupt. After 1933, New Deal relief programs helped reduce black unemployment substantially, but segregated public housing contributed to overcrowding, often demolishing more units than were built. Housing conditions in the Central area deteriorated during the 1930s, and African Americans continued to suffer discrimination in many public accommodations. The period from the late 1920s to the mid-1940s was one of political change for black Clevelanders. Although migration from the South slowed to a trickle during the 1930s, the black population had already increased to the point where it was able to augment its political influence. In 1927 3 blacks were elected to city council, and for the next 8 years they represented a balance of power on a council almost equally divided between Republicans and Democrats. As a result, they obtained the elections of HARRY E. DAVIS to the city’s Civil Service Commission and MARY BROWN MARTIN to the Cleveland Board of Education, the first African Americans to hold such positions. They also ended discrimination and segregation at City Hospital. At the local level in the 1930s, black Clevelanders continued to vote Republican; they did not support a Democrat for mayor until 1943. In national politics, however, New Deal relief policies convinced blacks to shift dramatically after 1932 from the Republican to the Democratic party. After World War II, Pres. Harry Truman’s strong civil-rights program solidified black support for the Democrats.

World War II was a turning point in other ways. The war revived industry and led to a new demand for black labor. This demand, and the more egalitarian labor-union practices of the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), created new job opportunities for black, Clevelanders and led to a revival of mass migration from the South. The steady flow of newcomers increased Cleveland’s black population from 85,000 in 1940 to 251,000 in 1960; by the early 1960s, blacks made up over 30% of the city’s population. One effect of this population growth was increased political representation. In 1947 Harry E. Davis was elected to the state senate, and 2 years later lawyer Jean M. Capers became the first black woman to be elected to city council. By the mid-1960s, the number of blacks serving on the council had increased to 10; in 1968 Louis Stokes was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives; and in 1977 Capers became a municipal judge for Cleveland. The postwar era was also marked by progress in civil rights. In 1945 the CLEVELAND COMMUNITY RELATIONS BOARD was established; it soon developed a national reputation for promoting improvement in race relations. The following year, the city enacted a municipal civil-rights law that revoked the license of any business convicted of discriminating against African Americans. The liberal atmosphere of the postwar period led to a gradual decline in discrimination against blacks in public accommodations during the late 1940s and 1950s. By the 1960s, both hospital wards and downtown hotels and restaurants served African Americans.

Despite these improvements, however, serious problems continued to plague the African American community. The most important of these was housing. As the suburbanization of the city’s white population accelerated, the black community expanded to the east and northeast of the Central-Woodland area, particularly into HOUGH and GLENVILLE. Expansion, however, did not lead to more integrated neighborhoods or provide better housing for blacks. “Blockbusting” techniques by realtors led to panic selling by whites in Hough in the 1950s; once a neighborhood became all black, landlords would subdivide structures into small apartments and raise rents exorbitantly. The result, by 1960, was a crowded ghetto of deteriorating housing stock. At the same time, segregation in public schools continued, school officials routinely assigned black children to predominantly black schools. In 1964 interracial violence broke out when blacks protested the construction of 3 new schools, as perpetuating segregation patterns. Frustration over inability to effect changes in housing and education, coupled with a rise in black unemployment that began in the late 1950s, finally ignited the HOUGH RIOTS for 4 days in 1966. Two years later, the GLENVILLE SHOOTOUT involved black nationalists and the police; more rioting followed. The resulting tension and hostility did not entirely destroy the spirit of racial toleration in Cleveland, however, as evidenced by the 1967 election of lifelong resident Carl B. Stokes as the first black mayor of a major American city (see MAYORAL ADMINISTRATION OF CARL B. STOKES). Since then, blacks have continued to be the most influential group in city council. The city again elected an African American mayor, Michael White, in 1989.

As migration from the South ended, Cleveland’s African American population stabilized in the 1970s and 1980s. Although the ghetto expanded into EAST CLEVELAND, fair housing programs and laws made it possible for middle-class blacks to have greater choice of residency. Eastern suburbs such as SHAKER HEIGHTS and CLEVELAND HEIGHTS absorbed large numbers of black residents by the 1970s, but managed to maintain integrated populations. In addition, some of the more blatant causes of the riots–such as the small number of black police officers–were partially resolved. But fundamental problems remained. Inner-city residents suffered high levels of crime, infant mortality, and teenage pregnancy in the 1970s and `80s, but the most significant obstacles for black Clevelanders remained economic in nature. The movement of black women into white-collar jobs after 1970 was more than counterbalanced by the growing unemployment or underemployment of black men, as good-paying industrial jobs declined or shifted to the suburbs. At the same time, the declining city tax base undercut funding for the public schools, making it more difficult for African American children to obtain the necessary skills demanded in the emerging post-industrial society. For many black Clevelanders in the late 20th century, economic progress had not kept pace with improvements in the political realm.

Kenneth L. Kusmer

Temple Univ.

Davis, Russell. Black Americans in Cleveland (1972).

Kusmer, Kenneth L. A Ghetto Takes Shape (1976).

Last Modified: 21 Jul 1997 01:26:36 PM

Plain Dealer article from December 31, 1995

BLACK HERITAGE BEGAN IN 1809

Plain Dealer, The (Cleveland, OH) – Sunday, December 31, 1995

Author: SHARON BROUSSARD PLAIN DEALER REPORTER

If ever there was a golden age for the black community in Cleveland, it was in the 1850s. It was then that a tiny group of blacks, numbering 224 out of a population of about 17,000, lived fully integrated lives.

They worked alongside white tradesmen, dined in restaurants, and mingled at lectures and musical recitals. They lived in neighborhoods among whites and sent their children to integrated schools. And at religious services – the most segregated hour of the week today – blacks worshiped with whites.

“At that point, Cleveland was a frontier town, a small city which was rapidly growing,” said Kenneth Kusmer, a noted historian on blacks in Cleveland and a Temple University professor.

“Cleveland was founded mostly by people from New England who were reformers. It was an anti-slavery center. As a result, blacks were considerably more accepted than in other cities.”

But that acceptance was fleeting. By the turn of the century, segregation and discrimination was prevalent. Any semblance of equality began a long, slow fade.

“There was a change in the national attitude toward black Americans,” Kusmer said. “The Civil War disappeared. The South became powerful again. The North took on a similar racial attitude of the South but not as intense. The discrimination was never legal, but always informal.”

Throughout the century, blacks struggled to regain their hold on Cleveland jobs, neighborhoods, and politics.

“As a historian, I see this [inequality] as a cumulative problem of the past. It has come back to haunt us.” Kusmer said.

Early settlers

The first black settler in Cleveland was George Peake, who arrived in 1809 with his wife and his two adult sons. At that time, the hamlet’s swampy surroundings were notable for mosquitos and malaria. If that wasn’t enough, Lorenzo Carter , Cleveland’s first permanent white settler kept a stranglehold on the Indian trade and employed “itinerant vagabonds,” who were menacing to prospective settlers.

The Peake family was well off and bought 103 acres of land west of the early settlment, in an areas that is today Lakewood. Peake then created a hand-mill for grinding grain that was popular among the settlers.

Other black families followed, many becoming as successful as their white counterparts.

“The people who migrated early were able to start businesses and develop trades and have more economic opportunity. The blacks who came were able to succeed, not absolutely on the basis of equality, but they were able to succeed,” said Kusmer.

While it is difficult to quantify the success the black pioneers enjoyed because of a lack of documents, historians cite John Brown and others. Brown was a barber who bought land that he later sold for $35,000, a sizeable sum in those days. John Malvin was an abolitionist and successful canal boat captain.

Others note Alfred Greenbriar, who owned a stable, and Madison Tilley, an excavating contractor who employed up to 100 men.

By 1850, a significant number of blacks had purchased property.

“I was surprised at the ability of blacks to move into skilled work,” said Kusmer, who studied 19th-century census records. The records indicated equal opportunity employment “relatively speaking on par with Irish immigrants, not the native-born whites,” Kusmer said.

Yet racism did exist. The Black Laws, a series of statewide codes in effect from 1804 to 1887, made Ohio, in general, less attractive to black settlement. According to the laws, a black who wanted to live in the state had to post a $500 bond as assurance against his becoming a pauper or a criminal and show a certificate of freedom. Blacks could not testify against whites, vote or run for office.

Blacks could not marry whites and, according to the Black Laws, their children couldn’t go to public schools or enter any of “the institutions of this state, viz: a lunatic asylum, deaf and dumb asylum, not even the poor house,” wrote John Malvin in his autobiography, “North Into Freedom.”

Despite these laws, white Clevelanders, who had become active in abolishing slavery, generally ignored the laws. But in southern Ohio, which was settled by white southerners, the Black Laws were strictly enforced.

“It was much more ambiguous and complex in the Northern states,” Kusmer said. “You might have segregation without the laws or have discriminatory laws but not have them obeyed.”

The very fact that these laws exsisted concerned Cleveland-area blacks. They agitated for the repeal of the Black Laws and abolitionist John Malvin organized a school in 1831 for black children who couldn’t attend public schools. He also waged a one-man battle against segregated pews in predominately white First Baptist Church.

“To that I objected,” he wrote. “Stating that if I had to be colonized, I preferred to be colonized at Liberia, rather than the House of God.” He was so successful that until the turn of the century, blacks attended integrated churches.

Other blacks became well known on the abolitionist lecture circuit. In fact, when Lucy Bagby, a fugitive slave, was ordered returned to her master in Virginia in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, security was tightened because black Clevelanders threatened to carry her off to safety.

William Howard Day, an Oberlin College graduate who moved to Cleveland in the 1840s, was a printer and traveling anti-slavery lecturer. He secretly wrote the constitution for John Brown’s doomed republic of freed slaves.

William Wells Brown, an ex-slave who escaped through the Underground Railroad and settled in Cleveland during the 1830s, was a historian, writer, and abolitionist lecturer, best known for writing “Clotel, or The President’s Daughter,” a novel about the alleged slave offspring of President Thomas Jefferson.

Slowly, black Clevelanders won many of their important battles. The Black Laws stayed on the books until 1887, but Cuyahoga County abandoned a registry recording the $500 bonds and certificates of freedom in 1851.

By the late 1840s, black children were allowed to attend white public schools and churches were so integrated that all-black churches grew very slowly, surviving on membership drawn from black Southern migrants who wanted down-home religion.

Racism had not completely fled from northeast Ohio, however. In 1859, The Plain Dealer, which supported the Democrats then considered to be the party of the South, would declare: “This is a government of white men. Let them establish a government of colored men.”

Still, those words were largely ignored. The Western Reserve was infected with abolitionist fever and Cleveland was one of the major stops on the Underground Railroad.

When the Civil War began, blacks who were forbidden to join the white troops in Ohio went to Massachusetts to join the all-black 54th and 55th regiments. In 1863, Ohio accepted black recruits for the war.

Blacks in Ohio gained the vote in 1870, and John Patterson Green was the first black elected justice of the peace three years later.

But, in less than four decades, race relations in Cleveland would take a turn for the worse.

Color line emerges

In 1880, there were only 2,000 blacks living in Cleveland out of a population of 160,000. Four years later, Ohio passed a Civil Rights Law forbidding discrimination in public places and amended it 10 years later.

The first black elected to City Council, Thomas Fleming, took office in 1909.

Other black councilmen followed including three in 1929, who engineered plans to stop a segregated hospital.

“In the 1920s, they flexed their political muscle,” said Kusmer. “When the city tried to institute a separate hospital, for example, it was defeated. They had political power in the City Council. …”

By 1920, the number of black residents would boom to 72,000. While there were no “white only” or “colored” signs posted in Cleveland, and police didn’t arrest blacks for sitting at lunch counters, the barriers to full integration, as opaque as they appeared, were rock hard.

Gradually, most blacks were barred from restaurants, segregated in theaters, and forced to live in the Central neighborhood of Cleveland, an area bounded by Euclid Ave. to the north, the railroad tracks to the south, east to E. 55 St., and west by Public Square. They were chased out of parks in white neighborhoods and not allowed in the YMCA or YWCA. Even more critically, blacks were hired for only the most menial jobs and kept out of apprenticeship programs and unions. Those who had the time and the money to sue did, but getting justice was too often like hitting the lottery – only the most naive would count on redress for every wrong.

The climate in Cleveland for blacks changed because of a combination of factors including a growing disregard for the plight of the blacks, Supreme Court decisions that supported segregation, the rise of white supremacy in the South and the influence of racist theories promoted by scientists. These theories claimed blacks were inferior because of smaller brain size or childlike characteristics.

“Cleveland had lost its earlier aura of equality in racial matters,” an attitude that was reflected throughout the nation, Kusmer said.

“You had some white liberals like the Jelliffes [who founded Karamu] but for the most part, Cleveland slipped into the pattern of other northern cities.”

The emerging color line was a blow to the black middle class. George A. Myers, a barber who was the black liaison for Marcus A. Hanna, a Republican boss, was told when he retired from his barbering franchise in 1930 that the hotel would replace the black barbers with white ones.

“It broke his heart and he died soon after,” said Kusmer. “Blacks who thought they would be accepted, who played by the rules, who were middle class and conservative in politics, found out they weren’t accepted by many people.”

Ironically, the public schools remained integrated for children and teachers, even assigning black teachers like Bertha Blue, who taught Italian immigrant children for more than 30 years in Little Italy.

Between 1920 and 1940, the number of blacks in Cleveland had almost tripled from 34,451 to 84,504. Only the Great Depression acted as a brake to white flight to the suburbs, said Adrienne Lash Jones, history professor at Oberlin College and an expert on black history in Cleveland during the 20th century. Even today older blacks who grew up in the 1930s can recall playing street games and jumping rope with white friends in Central.

But as soon as the Great Depression lifted, the ghettoization of Central continued. “What was happening was that they did live in close proximity. They did get along,” she observes.

“But as soon as the whites could get out of there, they did.”

Despite the discrimination in Cleveland, Southern blacks were lured here by a feeling that life would be better up North. Blacks doubled their numbers between 1930 and 1950 to 147,847 from 71,899.

Their arrival spurred a bigger business community. The Central area became home to black-owned stores, gas stations, restaurants, doctors’ and lawyer’s offices, and funeral homes, which supported a growing black middle class. By the 1950s, there were black-owned savings and loans and insurance companies.

There were some success stories too. Track star Jesse Owens started winning races at East Technical High School in 1933. He set world records in the Berlin Olympics in 1936. The great American writer Langston Hughes who would be a major part of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, wrote poetry as a student at Central High School.

Yet there were few exceptional students. From the turn of the century, black Clevelanders struggled for better schools, housing and job opportunities.

In the 1940s, a group of blacks took the city to court for its refusal to hire more than a token number of blacks in the booming wartime industries. Blacks weren’t hired in the plants until near the end of the war.

The prosperity from World War II would change the look of the ghetto and the outlook of its residents. Veterans returning from a war where they had been asked to die for their country did not easily accept the second-class citizenship foisted upon them.

“They were disappointed, frustrated and angry,” historian Jones said. That frustration would eventually lead to the election of the city’s first black mayor in 1967.

Meanwhile, rising income would allow the black middle class, many anxious to rear their children in stable, safe neighborhoods, to leave the older, more deteriorated housing stock in the Central area. When they could, they pushed east beyond E. 55th St. and north beyond Euclid Ave.

Unscrupulous real estate agents capitalized on whites’ fears of blacks and urged many whites to sell their homes so they could sell them at higher prices to black buyers. The neighborhoods of Glenville, Hough and Mount Pleasant saw a sharp increase of black residents.

Whites, in turn, moved into eastern or western suburbs where home prices and mortgage loan practices kept blacks out.

By the 1940s, the black business community had relocated from Central Ave. to Cedar Ave. near E. 105th St.

“There were grocery stores. Art’s Seafood restaurant was on Cedar for many, many years,” Jones said. “There were good restaurants and white people would come to the “black and tan” clubs to listen to music. But blacks couldn’t go to the all-white clubs.”

No matter how nice certain sections were, the stagnation and poverty of the ghetto never seemed to be far behind. Ironically, urban renewal in the older sections of Central pushed poor blacks into Hough and Glenville.

Landlords profited by turning single-family homes into two-family homes and later into overcrowded shacks. City inspectors didn’t monitor the housing stock. Redlining by banks and insurance companies increased the blight, even in middle-class black havens like Glenville and Mount Pleasant.

“As neighborhoods became predominately black, you see a decline in the ability to borrow money for home improvements. You could get money for a car or a refrigerator, but you couldn’t get a home improvement loan,” Jones said.

Indeed, the Federal Housing Administration underwriting manual from the 1930s warned agents to be wary of writing mortgage or home improvement loans in areas where “inharmonious” racial groups existed because they might lower property values. Loans should ideally be given in communities with zoning regulations and restrictive covenants, according to the FHA rules. It was a standard that Central, Hough, Glenville and other areas could not meet.

By the 1960s, black neighborhoods were bursting at the seams – about 251,000 blacks lived in Cleveland – most in deteriorating Central and nearby neighborhoods. Battles were not far behind. The first were waged against school segregation and the quality of education.

The NAACP had complained about the quality of education for black children since the 1920s. Over time it worsened. Youngsters had to attend overcrowded schools in shifts. Central High School offered vocational classes and the children of southern migrants had to attend remedial schools.

One demonstration against the building of schools designed to prevent integration led to the death of protester Bruce Klunder, a white minister, in 1964.

Two years later, the Hough riots would break out, reportedly sparked by a white bartender accused of refusing to give a black man a drink. Four people were killed, 30 people injured. But the fuse was set long before, said Jones.

“There were overcrowded conditions and lots of frustration,” she said. `We were in a downturn economically. People were having a hard time. Cleveland was very racist. People found all kinds of obstacles in employment. People came here to live better and they weren’t living better.’

The riot was also a sign of the times, she said. “It wasn’t just the blacks. There was a student rebellion and the women’s movement. It was a societal rebellion and disruption. If you see it in isolation, you miss the whole context.” Against this backdrop, Carl B. Stokes would be elected mayor in 1967, after losing in 1965. His brother, Louis Stokes was elected to Congress in 1968. Carl Stokes appealed to black voters and worked hard at getting the votes of whites, knowing they were wary of putting a black man in the mayor’s seat.

“He was very charismatic, like a black John Kennedy,” Jones said. “He was a good person and he had the right beginnings. He was right up from the bootstraps. A street boy who made good.”

In 1968, Glenville exploded in a shootout led by nationalist Fred “Ahmed” Evans. The exchange of gunfire left seven people dead, 15 wounded and led to looting and arson. Stokes’ reputation was tarnished among some voters when it was discovered that public money had gone to Evans’ nationalist group.

He declined to run in 1971, but Stokes had entered the top ranks of city government and paved the way for other black powerbrokers. George Forbes became president of City Council in the 1973, and Mayor Michael R. White, the second black mayor, was elected in 1989.

Back in neighborhoods like Glenville, Hough and Mount Pleasant, the ’70s and ’80s would be marked by an escalating flight to the suburbs by the black middle class. With housing discrimination outlawed, middle-class blacks headed to Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights and other eastern suburbs. By the 1980s, one-fourth of all Cuyahoga blacks lived in the suburbs. The city’s default in the ’70s, visible deterioration and a controversial school desegregation plan spurred them on as it did other racial groups.

“Anyone who could get out of Cleveland, both blacks and whites, did because of the schools. … The flight is related to the deterioration of the school system,” said Jones. She moved from Glenville to Shaker Heights in the 1960s because of the poor quality of schools.

In some ways, the racist legacy of the beginning of the 20th century is a template for black and white Cleveland today. Most of the whites in Cleveland still live on the West Side and in the western suburbs. Most of the blacks live on the East Side and in the eastern suburbs, some of which have a higher percentage of black residents than does Cleveland.

Roughly half of Cleveland’s 492,000 population is black and a great deal of it is poor, according to the Census Bureau. About 42 percent of Clevelanders live below the poverty line, that number soars to half of the black population and 56 percent of Cleveland’s adult black males do not have a job, according to the U.S. Census.

Urban poverty researchers Claudia J. Coulton and Julian Chow note that poor people in Cleveland have become more concentrated in certain neighborhoods, and these high-poverty neighborhoods are spreading to the edges of the city. “If this trend were to continue,” the researchers write, “nearly three-quarters of the city of Cleveland [census] tracts would reach high-poverty status before the year 2000.”

In addition, Cleveland is one of 10 American cities where the poor and the affluent are to a great degree spatially isolated from everyone else, Coulton and her colleagues found. “Cleveland and nine other cities have this most extreme pattern of the poor being concentrated in the central cities in particular neighborhoods and the affluent being concentrated at the outskirts,” said Coulton, co-director of the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University.

The result of this extreme isolation is that the poor and unemployed have little contact with the middle and upper classes, whose values are predominant in society. Likewise, the affluent have little contact with the poor, so they have no firsthand knowledge of the hardship facing them and thus, would be less inclined to help them, researchers say.

Still, life in Hough, Glenville and Central is not all bleak. Redevelopment has brought new, and in some cases upscale, homes and shops in the area during the last five years. Lured by generous tax benefits, some of the middle class have moved back.

“The development of political leadership is a bright spot,” said Jones. “The opportunities are available if you are determined. Of course, you have to become well-trained in schools and that’s a problem. Yet, there are blacks in positions they didn’t hold in the 1960s. And with the development of the communty college, there are a significant number of black people who are able to take advantage of higher education opportunity. The White administration has changed the way the city looks.”

But she still worries about the future of blacks in Cleveland. “The question of race is still important,” she said. “We can look at the progress, but we should not delude ourselves that the underlying issues of poverty – the lack of bank loans, the high rates of unemployment for black youths – are solved.”

From the Ohio Historical Society

Praying Grounds: African American Faith Communities A Documentary and Oral History

From CSU Special Collections