Cleveland Public Library (top) George Myers/WRHS (bottom)

Cleveland Public Library (top) George Myers/WRHS (bottom)

The Best Barber in America

By John E. Vacha

When Elbert Hubbard called Cleveland’s George Myers the best barber in America, people listened.

Hubbard’s was a name to be reckoned with in the adolescent years of the Twentieth Century. His Roycroft Shops in New York were filling American parlors with the solid oak and copper bric-a-brac of the arts and crafts movement. His periodicals, The Philistine and The Fra, brought him national recognition as the “Sage of East Aurora.” One of his essays alone, “A Message to Garcia,” ran through forty million copies.

You could say he was the Oprah of his day.

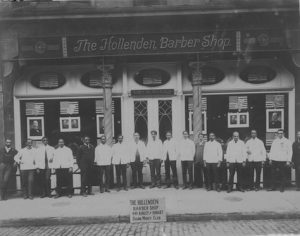

Myers himself was certainly aware of the value of a testimonial from Elbert Hubbard. Across the marble wall above the mirrors in his Hollenden Hotel establishment, he had imprinted in dignified Old English letters over Hubbard’s signature, “The Best Barber Shop in America!”

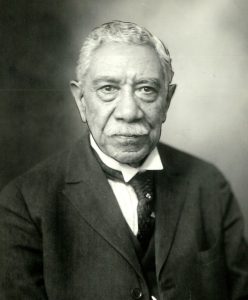

Though he played on a smaller stage, George A. Myers managed to compile a resume as varied and impressive as Hubbard’s. He was recognized as a national leader and innovator in his profession and became one of the most respected members of Cleveland’s black bourgeoisie. As the confidant and trusted lieutenant of Mark A. Hanna, he became a force in Ohio Republican politics. Behind the scenes, he campaigned effectively to maintain the rights and dignity of his race. In later years he maintained a voluminous correspondence with James Ford Rhodes, providing the historian with his inside knowledge of the political maneuvers of the McKinley era.

It wasn’t a bad record for a barber, even for one who had bucked his father’s wishes for a son with a medical degree. George was the son of Isaac Myers, an influential member of Baltimore’s antebellum free Negro community. Like Frederick Douglass, the senior Myers had learned the trade of caulker in the Baltimore shipyards. When white caulkers and carpenters struck against working with blacks, Isaac took a leading role on the formation of a cooperatively owned black shipyard. He became president of the colored caulkers’ union, and that led to the presidency of the colored wing of the National Labor Union.

Born in Baltimore in 1859, George Myers was ten years old when his mother died in the midst of his father’s organizing activities. Isaac took George along on a trip to organize black workers in the South and then sent him to live with a clergyman in Rhode Island. George returned to Baltimore following his father’s remarriage and finished high school there but found himself excluded from the city college because of his race.

That’s when George decided to call a end to his higher education, despite his father’s desire that he enroll in Cornell Medical School. After a brief stab as a painter’s apprentice in Washington, he returned to Baltimore to master the barber’s trade.

Young Myers came to Cleveland in 1879 and found a job in the barber shop of the city’s leading hotel, the Weddell House. He had come to the right place at the right time. Cleveland was in the midst of its post-Civil War growth, and its barbering trade was dominated by African Americans. Myers soon became foreman of the shop, and among the influential patrons he serviced was the rising Republican politico, Mark Hanna.

His upscale clientele served Myers well when a new hotel, the Hollenden, challenged the supremacy of the Weddell House. The Hollenden’s owner was Liberty E. Holden, publisher of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, who advanced Myers four-fifths of the capital required to operate the barber shop in his hostelry. The remaining $400 was provided by a select group which included Hanna’s brother Leonard, his brother-in-law Rhodes, ironmaster William Chisholm, and future Cleveland mayor Tom L. Johnson. “Suffice to say that I paid every one of you gentlemen,” Myers later recalled to Rhodes with pardonable pride. Once again, Myers had made a good career move.

Located in the booming downtown area east of Public Square, the Hollenden quickly became the gathering place for the city’s elite as well as its distinguished visitors. One of its premiere attractions undoubtedly was the longest bar in town. Another was its dining room, which was appropriated by the politicians and reputedly became the incubator of the plebian ambrosia christened “Hanna Hash.”

When not eating or drinking, politicians naturally gravitated to the hotel’s barber shop, which, like politics, remained a strictly male domain in the 1880s. Myers served them so well that in time a total of eight U.S. Presidents, from Hayes to Harding, took their turns in his chair, along with such miscellaneous luminaries as Joseph Jefferson, Mark Twain, Lloyd George, and Marshall Ferdinand Foch. As for the regulars, according to the eminent neurosurgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing, it became “a mark of distinction to have one’ s insignia on a private shaving mug in George A. Myers’s personal rack.”

In such a milieu, it was almost inevitable that Myers himself would get involved in “the game,” as he called politics. Mark Hanna had hitched his wagon to a rising star in Ohio politics named William McKinley and invited Myers on board for the ride. As a Cuyahoga County delegate to the Ohio State Republican Convention, Myers helped nominate McKinley for governor in 1891. He supported the Ohioan for President as a delegate to the Republican National Convention the following year. McKinley fell short that time, but Myers cast the deciding vote to place a McKinley man on the Republican National Committee, giving the Hanna forces a strategic foothold for the next campaign.

As the crucial campaign of 1896 approached, Hanna decided that Myers was ready for greater responsibilities. A vital part of Hanna’s strategy to secure the nomination for McKinley involved capturing Republican delegations from the Southern states. Since most white Southerners at the time were Democrats, blacks enjoyed by default a disproportionate influence in the Southern Republican organization.

That’s where Myers came in, as the Cleveland barber undertook to organize black delegates for McKinley not only in Ohio but in Louisiana and Mississippi as well. The convention took place in the segregated city of St. Louis, where Hanna further entrusted Myers with the delicate task of overseeing accommodations and providing for the entertainment of the colored delegates.

McKinley, of course, won not only the nomination but went on to take the election. Hanna then had Myers installed as his personal representative on the Republican State Executive Committee, where Myers worked to integrate the Negro voters of Ohio into the Hanna machine. One of Myers’ guiding principles was the discouragement of segregated political rallies in order “to demonstrate that in party union there is strength.”

Myers had developed a deep personal attachment to Hanna, whom he affectionately dubbed “Uncle Mark.” “His word is his bond and he measures white and black men alike, — by results,” wrote Myers of his political patron. “He is loyal to his friends, a natural born fighter and has the courage of his convictions.

It isn’t surprising, then, that Myers was willing to go to extraordinary measures to help secure Hanna’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1897. State legislatures then held the power of appointment to that office, so when Uncle Mark was still a vote short of election, Myers approached William H. Clifford, a black representative from Cuyahoga County, and bluntly paid for his vote in cold, hard cash. “It was politics as played in those days,” Myers later explained to Rhodes. “When I paid Clifford to vote for M.A. I did not think it a dishonest act. I was simply playing the game.”

Though McKinley had offered to reward him for his support with a political appointment, Myers was reluctant to neglect his thriving business for an active role in “the game.” The barber showed no reluctance to cash in his political capital for the benefit of fellow African Americans, however. He arranged the appointment of John P. Green, the originator of Labor Day in Ohio, as chief clerk in the Post Office Stamp Division in Washington. This earned Myers the enmity of Harry C. Smith, publisher of the black weekly Cleveland Gazette, who saw the barber’s influence as a threat to his own leadership among the city’ s Negro voters. As the Cleveland Plain Dealer called it in 1900, “George A. Myers is without doubt the most widely known colored man in Cleveland and probably the leading politician of his race in Ohio.”

Among the other appointments for which Myers smoothed the way were those of Blanche K. Bruce as register of the U.S. Treasury and Charles A. Cottrell of Toledo as collector of internal revenue at Honolulu. Only when he saw his livelihood threatened through political action did Myers act in his own interest. In 1902 he asked Hanna “to do me the favor to use every influence at your command” to defeat a proposed state law which sought to place Ohio’s barbering business under the control of a state board. Myers feared that this licensing board, like the barber’s schools, would come under the domination of labor unions which excluded blacks. Hanna promised to “take it up with my friends at Columbus and see if something cannot be done.”

Evidently something could be done, and the bill was defeated.

After Hanna’s death in 1904, Myers dropped his active involvement in politics. “I served Mr. Hanna because I loved him,” Myers told Rhodes, “and even though I put my head in the door of the Ohio Penitentiary to make him U.S. Senator, I would do the same thing again, could the opportunity present itself.” With both Hanna and McKinley gone, however, Myers wasn’t about to stick his neck out for anyone else. Instead, Myers tended to business with impressive results.

By 1920 he had more than thirty employees in his shop, including seventeen barbers, three women’s hairdressers (barriers were falling by then), six manicurists, and two pedicurists. Myers claimed that his was the first barber shop in Cleveland to provide the services of manicurists.

In fact, Myers was on the cutting edge (we wanted to avoid the cliche, but couldn’t resist the pun ) of numerous innovations in the trade. He was one of the first barbers to adopt porcelain fixtures and install individual marble wash basins at each chair. He also pioneered in the use of sterilizers and humidors.

The Koken Barbers’ Supply Company of St. Louis incorporated Myers’ suggestions in the development of the modern barber chair and solicited pictures of Myers and his shop for its house newsletter.

From the standpoint of his busy patrons, perhaps the most appreciated innovation of Myers was the telephone service he provided at each chair. “While having his hair cut a patron may talk to his home or transact business,” marvelled a contemporary trade journal.

“A desk phone is plugged in like a stand lamp and removed when not in use.”

One practice that earned Myers some sharp barbs from Harry Smith was the latter’s allegation that blacks were refused service in the Hollenden barber shop. On the basis of contemporary custom, it was probably true. Another black editor writing on discrimination in Cleveland at the turn of the century described how blacks were told by white barbers to “Go to one of your own people,” only to be told by some of their own, “Now men, we would like to work on you but you know we can’t do it. It would kill our business.” In Myers’ exclusive shop, blacks likely were welcome only behind the barber chairs. To Myers, it probably was simply a case of how that game happened to be played. When Booker T. Washington was organizing the National Negro Business League in 1900, he urged Myers to appear on the program at Boston.

“It is very important that the business of barbering be represented, and there is no one in the country who can do it as well as yourself,” wrote Washington. “We cannot afford to not have you present.”

Nevertheless, Myers demurred. Identifying oneself as “a colored business man,” he once wrote, was tantamount to “an admission of inferiority.” A dozen years later, Washington recommended Myers to head a Republican drive to organize the Negro vote in the presidential election.

Though flattered, Myers turned this offer down too, on account of the press of business. His application to his profession rewarded him well enough.

Myers revealed to Rhodes that he had paid an income tax of $1,617 in 1920, on gross receipts of $67,325. That put him in the upper brackets of Cleveland’s black middle class, where he assumed a position of social as well as business leadership.

Out of a city of close to 400,000 at the turn of the century, Cleveland’s African Americans formed a rudimentary minority of around ten thousand. Though not yet completely ghettoized, they tended to form their own churches, social organizations, and neighborhoods. Myers belonged to the city’s oldest black congregation, St. John’s A.M.E., and was a founding member of the segregated Cuyahoga Lodge of Elks. As a member of the Euchre Club, he belonged to the lighter-skinned social elite of the black community. With other black barbers and service workers, he also formed a Caterers’ Club that became famed for the prestige of its annual banquets.

Yet Myers wasn’t entirely circumscribed by the color line. He was a member of the civic-minded City Club and the Early Settlers Association. According to Cleveland safety director Edwin D. Barry, Myers “had more white friends than any colored man in Cleveland.”

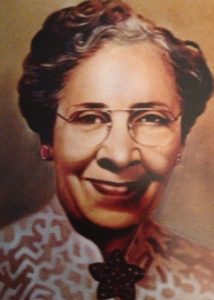

The very proper Victorian parlor of the Myers home on Giddings Avenue was once pictured in the Sunday magazine of the Plain Dealer. Following a divorce from his first wife Sarah, Myers had wed Maude Stewart in 1896. A son from the first marriage and a daughter from the second both became teachers in Cleveland’s public schools.

Despite his father’s activities as a labor organizer, George Myers had become as conservative as any Republican businessman. His own shop was a nonunion one, though his employees seemed content with the arrangement. He was genuinely upset over a May Day riot in the streets of Cleveland, consoling himself with the reflection that “Negroes are neither Socialist, Anarchist nor Bolshevist.”

Although keeping a well-stocked wine cellar for himself, Myers was in favor of Prohibition.

“I favored prohibition for the other fellow — some of my employees–and this is the secret of the Prohibition victory,” he admitted frankly to Rhodes.

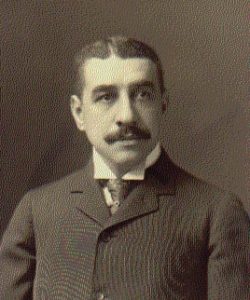

In personal appearance, Myers was always a good advertisement for his tonsorial skills. Trim throughout his life, he displayed a low, full hairline in youth, to which a well-shaped mustache added dignity. A fall down the elevator shaft in a customer’s home once broke his leg and foot, giving him a limp for years and enabling him to forecast the weather afterwards.

Following World War I, Myers purchased a new home in the predominantly Jewish Glenville neighborhood, appropriating the entire third floor for his sanctum sanctorium. Half of it became a billiard room, the other half his library. There he was said to have assembled one of the country’s most comprehensive collections of books by and about African Americans.

It was books that formed the common bond between Myers and James Ford Rhodes. After Rhodes retired from business to write history, Myers would walk over to his Euclid Avenue mansion to give Rhodes his daily shave and trim. On the way, he would often pick up a bundle of books for Rhodes from the library of the Case School of Applied Sciences, then still located downtown. “Me and my partner Jim are writing a history,” he once explained to a curious friend.

“Jim is doing the light work and I am doing the heavy.”

In time Rhodes moved to Massachusetts, where he continued issuing his magisterial “History of the United States From the Compromise of 1850.” As he approached the McKinley volume, Rhodes discovered that Myers might again be of help to him–this time with some of the light work. The historian was primarily interested in the barber’s knowledge of the inside workings of the Hanna McKinley political machine. When the volume was completed, he acknowledged his indebtedness in print “to George A. Myers of Cleveland for useful suggestions.”

Myers and Rhodes covered a wide range of topics in their letters, however, from old Cleveland acquaintances to World War I. When Herbert Croly published his reverential biography of Mark Hanna, Myers complained to Rhodes that he scarcely recognized the subject. “We knew Mr. Hanna to be a rough brusque character with an indomitable will of his own that respected the rights of no one who stood in the way of his successful accomplishment of the object he had set out to accomplish,” he wrote.

World War I proved to be a watershed in the racial thinking of George Myers. After fighting for freedom on the Western Front, Myers predicted to Rhodes that “the Negro will not submit to the atrocities and indignities of the past and present in silence.” Yet Myers was worried about another phenomenon of the war, the Great Migration of Southern blacks to Northern industrial cities. Cleveland’s small, comfortable black minority had suddenly tripled in size, he informed Rhodes. “Many of the Negroes are of the lowest and most shiftless class,” he wrote.

“Where Cleveland was once free from race prejudice, it is now anything but that….”

Prior to the war, Myers had tended to subordinate group solidarity in favor of individual enterprise. He was slow to join the N.A.A.C.P. and the Urban League. Although he supported Booker T. Washington’s efforts at vocational uplift at Tuskegee and was acknowledged by his secretary as “Mr. Washington’s most intimate, personal friend living in Cleveland,” Myers was consistently critical of any support by Washington of separate but equal welfare agencies. He regretted Washington’s endorsement of “in reality a Jim Crow” Y.M.C.A. branch in Cleveland and similarly objected to the formation of the Phillis Wheatley Home for single African American girls.

“Segregation here of any kind to me is a step backward and will ultimately be a blow to our Mixed Public Schools,” wrote Myers to Washington.

Myers preferred to fight racism by private initiative behind the scenes, as when he wrote the editor of the Plain Dealer to protest the paper’s use of the terms “darkies” and “negress.” The practice was halted, though Myers had to repeat his admonition after the war to the paper’s next editor. With less success, Myers also conducted a letter campaign against the screening in Ohio of the Klan-glorifying movie, “The Birth of a Nation.”

But the tensions raised by the Great Migration ultimately caused Myers to adopt a more contentious approach. The clincher probably occurred in 1923, when the Hollenden management informed Myers that his black employees would be replaced with whites effective with his retirement. European immigrants had been challenging the black supremacy in the barbering business since 1908, when James Benson had lost his lease in The Arcade.

In order to save his staff’s jobs, Myers postponed his retirement despite a heart condition brought out by an attack of influenza. A stronger tone entered into his exchanges with the white establishment.

When racial outbreaks loomed over the use of a swimming pool in Woodland Hills Park by Negroes, Myers prevailed on the safety department to station two black policemen there.

He was outspoken in his responses to a 1926 Cleveland Chamber of Commerce survey on immigration and emigration. He placed the blame for the squalid housing conditions in Cleveland’s “black belt” squarely on the Cleveland real estate interests for refusing to rent or sell desirable habitation to colored. Myers also scored the business community in general for its failure to provide economic opportunities for the Negro youth coming out of the schools. “There is not a bank in Cleveland that employs any of our group as a clerk, teller or bookkeeper,” he wrote, “scarcely an office that use any as clerks or stenographers and no stores, though our business runs up in the millions; that employ any as sales-women, salesmen or clerks.”

To Judge George S. Adams, Myers observed that “while I do not condone crime, (all criminals look alike to me), the negro, morally and otherwise, is what the white man has made him, through the denial of justice, imposition and an equal chance.” While the Negro community of Cleveland was working to assimilate the newly arrived immigrants from the South, he told Congressman Chester C. Bolton, “We who formerly lived here before the influx cannot carry the burden alone, nor should we. The industrial interest of the north forced this problem upon us….”

In the late 1920s Myers joined his old rival, Harry Smith of the Gazette, in a public campaign against the establishment of a Negro hospital in Cleveland. In a letter to the Plain Dealer he refuted, on the basis of his own personal experience, charges that blacks were turned away from or refused private rooms at City Hospital. Cleveland was on its way to becoming “one of the greatest medical centers of the world,” Myers asserted, and his people wanted to enjoy, “in common with all others, the benefit of the greatest medical skill and attention that the world has ever known.”

It wasn’t only equal care that Myers was concerned with, but equal opportunity for African Americans in the medical profession. He and Smith also fought for several years to gain admission of colored interns and nurses at City Hospital. City Manager William Hopkins might accuse Myers of having “gone over to Harry Smith bag and baggage,” but City Council finally rewarded their efforts with passage of a resolution granting the desired hospital privileges.

The following morning, January 17, 1930, as his daughter Dorothy drove Myers to his streetcar stop, he told her he was feeling better than he had in a long time. That was good, for at breakfast he had told the family that he faced the most difficult task of his life that day. Unable to continue working any longer, the seventy- year-old barber had finally sold out to the Hollenden. Now he had to inform his employees that they were effectively out of jobs.

He worked all morning, telling the staff just before noon that there would be an important meeting upon his return from lunch. Myers then walked a couple of blocks to the New York Central office in the Union Trust Building to purchase a ticket for a rest cure in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Reaching for his change, he suddenly reeled, grabbed at the counter, and crumpled to the floor.

Even before they could carry him to the building’s dispensary, Myers was dead of heart failure. Once before, after risking his career and reputation to make Mark Hanna a Senator, George A. Myers had withdrawn from “the game” of politics. Now, faced with what would undoubtedly have been the most painful confrontation of his career, he was released by death.

Eulogies poured in from both sides of the color line.

“His death removes a potent factor that those of the race in Cleveland can ill afford to lose at this time,” wrote his old adversary and recent ally, Harry Smith.

City Manager Hopkins estimated his correspondence with eminent men as “good enough and unusual enough to justify its preservation.” That also turned out to be the judgment of history.

ADDITIONAL READING

Russell H. Davis, Black Americans in Cleveland: From George Peake to Carl B. Stokes, 1796-1969 (Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, 1972).

John A. Garraty (ed.), The Barber and the Historian: The Correspondence of George A. Myers and James Ford Rhodes, 1910-1923 (Columbus: The Ohio Historical Society, 1956).

Felix James, “The Civic and Political Activities of George A. Myers, “The Journal of Negro History”, Vol. LVIII, No. 2 (April, 1973), pp. 166-178.

Kenneth L. Kuzmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976).

The George A. Myers Papers (Columbus: Ohio Historical Society Archives)

This article first ran in Timeline Magazine, Jan/Feb 2000.