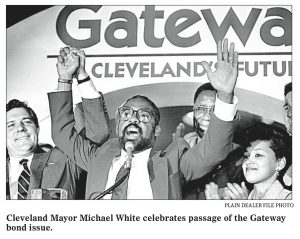

But White won a quarter of the vote here in a five-way mayoral primary Oct. 3, enough to make him the surprise contender in the Nov. 7 runoff and, according to most observers, the likely next mayor of Cleveland.

His second-place finish behind City Council President George Forbes in the nonpartisan primary made history in this gritty town, and not just because it guarantees that Cleveland will elect its second black mayor ever. In a city where politicians have traded on racial divisions for more than two decades, White appears to be succeeding with a message and style that transcend race.

A mid-October poll by the Cleveland Plain Dealer showed White leading Forbes, the tough-talking, iron-fisted boss of Cleveland’s predominantly black East Side, 46 percent to 27 percent. If White wins, it will be because enough voters on both sides of town see themselves as united rather than divided by their city’s agonizing problems, from drugs to bad schools to a declining middle class.

“It’s that appeal that (mayoral candidate David) Dinkins had in New York: Everybody’s not a racist; let’s get together. . . . His message was one of hope, and that’s all,” Roldo Bartimole, editor of a Cleveland political newsletter, said of White’s surprising primary campaign.

“We’ve had leaders whose stock in trade has been to maintain their own power by dividing the community,” White said after a recent day of campaigning. “White politicians who go to the white community and say, ‘Your enemies are black folks’; black politicians who go to the black community and say, ‘Your enemies are white folks’; then those two leaders go in the back room and make a deal while we’re fighting each other.”

His best example is Forbes, Cleveland City Council president for 16 years and a man considered at least equal in power to outgoing Mayor George V. Voinovich.

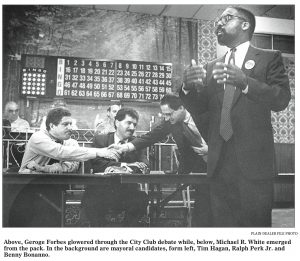

Known both for roughhousing his opponents – he threw a chair at a fellow councilman once and called one of his mayoral rivals a pimp – and for his ability to negotiate big deals for downtown development, Forbes has the backing of most of Cleveland’s major business and labor groups. But his base is on Cleveland’s East Side, whose voters he has courted for a quarter-century via a popular radio talk show, freely labeling white opponents bigots and black ones as Uncle Toms.

“He’s been a macho pol who’s yelled race whenever it’s been convenient,” said Bartimole. “If he were white,” added City Councilman Jay Westbrook, ”he’d be Frank Rizzo.”

Even Forbes himself admits that he’s been “projected as being a black racist,” though he calls that perception “not adequate.” He was the easy favorite in the primary and was expected to face one of three established white politicians in the runoff. White, a little-known state senator, was a long shot at best.

“Nobody anticipated that 25 percent of the white West Side would bypass a white county commissioner, the white clerk of courts and the white head of the school board to vote for Mike White,” said Carl Stokes, who was elected Cleveland’s first black mayor (the first in a major U.S. city) in 1967.

So far, the campaign has consisted of nasty charges that White beat his former wives and that he maintains slum property in black neighborhoods. A newsletter circulating on the East Side also labeled White a “beast among us” and called him the handpicked candidate of the white power structure.

Forbes has tried to soften his own blustery image, appearing in commercials with his family and arguing that his experience qualifies him to continue Cleveland’s struggling renaissance. Endorsements have also come from prominent black leaders, including Jesse Jackson – a move that White says belies Jackson’s populist image.

White said Jackson is “becoming nothing more than another rank black politician who cares more about his own political base than about black people in general.”

More articulate than Forbes, White has played on Forbes’ reputation for racial antagonism to paint himself as primarily an advocate for the city, rather than for blacks.

But taking that message to black voters challenges not only Forbes but also a political style rooted in the civil rights era, observers say.

“The phase of black politics that was launched here with Carl Stokes (was) a kind of patronage system which was kind of basic: Get blacks into jobs and get contracts moving toward black business people, without much thought to performance,” said Tom Bier, an urban studies professor at Cleveland State University.

“The next phase has to do with effectiveness. The aches and pains produced by poor performance are so strong that it just isn’t good enough to have a black person in the job. They’ve got to perform.”

Cleveland lost 175,000 people during the 1970s, after ghetto riots and court-ordered school busing prompted many middle-class whites to flee. In the ’80s, they were joined by thousands of middle-class blacks, leaving a city that has dropped from eighth-largest in the nation to about 25th. Its remaining population is about half white and half black.

Although its downtown has recently seen an influx of new office buildings, its schools are in desperate shape, public housing is miserable and neighborhood services on both sides of town have declined.

While even some of White’s supporters say his policies might not differ drastically from Forbes’ once in office, they argue that the city’s condition gives him a powerful set of issues with which to campaign. “Can anybody turn around an aging Midwestern industrial city that’s lost its middle class overnight? No,” said Jim Rokakis, who represents the 15th Ward on City Council. “But (White) will have a chance, more than George Forbes, to bring blacks and whites together.”

1979 CSU

1979 CSU ![]()