The mayor wakes at 5 a.m., without an alarm clock, on the day he will announce the end of his reign in Cleveland.Instantly alert, he turns to wake his wife JoAnn. They have planned the day, practically down to the minute, and Mike White wants them to start it together. He’s surprised at how calm he feels. Neither nervous nor emotional, just prepared. Battling a bit of a cold, he showers, dresses and has a cup of coffee.

Today’s the day, he thinks. Let’s do this. At 5:30 a.m.. White calls his press secretary, Brian Rothenberg, telling him to be at White’s East Boulevard home at 7 a.m. Other key staff members are told to arrive at the same time. None of them know what to expect. Whenever Rothenberg has pressed White about running again, the mayor has flashed his wide smile, but said nothing.

By necessity, the mayor’s family knows more. So that they could make plans to attend the announcement. White and his wife began calling relatives two days earlier. Other than family, only three people know of White’s decision: his “guardian angel,” Sam Miller of Forest City Enterprises; his “other sister,” Carole Hoover, former president of the Greater Cleveland Growth Association; and his chief of staff, Judith Zimomra.

Nobody else expects the day that will follow.

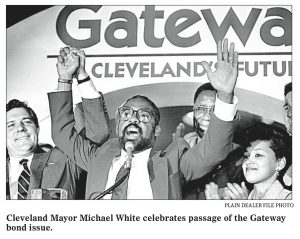

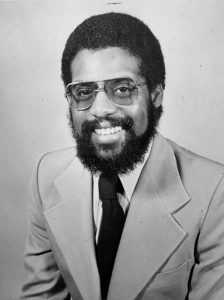

After 12 years as mayor, five as a state senator and eight as a Cleveland city councilman, White plans to announce that he will never again seek elected office. The man who began his career campaigning for Carl Stokes as the age of 13 — passing out literature and cleaning bathrooms in campaign headquarters — has spent three terms in the same office Stokes occupied as Cleveland’s first black mayor. Despite his power and self-professed love of the job, White claims he’s ready to leave.

Brilliant. Tyrannical. Compassionate. Vindictive. Nurturing. Aloof. Each of these adjectives has been used to describe White. In reality, he is a cocktail of them all-— a blend of both good and bad that is reflected in his emerging legacy. He’s considered by many to be the energy that fueled Cleveland’s decade of progress. More recently, he’s helped pass a levy to repair the city’s public schools and has battled to jump-start the expansion of Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. But he’s also been accused of failing to deliver to the city a new convention center, bungling plans for the lakefront and frustrating business and community leaders with a leadership style that leaves no room for second opinions.

in his past and said little about his future. Most of all, he surprised just about everyone, shaking Cleveland’s political landscape in nine words: “I will not seek re-election to a fourth term.”

***

The telephone rings just as Cleveland schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett steps out of the shower. It’s the mayor, saying he needs to speak with her.

“Well, when?” she asks.

“I’m at your front door.”

Byrd-Bennett looks out the upstairs window and sees the mayor on her front steps, holding her newspaper. Her hair uncombed and wearing no makeup, the CEO of Cleveland schools comes downstairs to let him in. He’s wearing a double-breasted suit and white shirt. She has on a robe and slippers.

The two sit down at the kitchen table, a vase of yellow roses between them. “I’ve been doing a lot of thinking lately,” the mayor tells her. “You know how I feel about you personally and professionally. You know the respect I have for your work. But I’ve come to a decision. I’ve decided I will not seek a fourth term.”

Byrd-Bennett looks out the window into the sunny morning, then turns to the mayor.

“I’ve given it a lot of thought,” he assures her. “And I wanted you to know and I wanted you to know why. Are you OK?”

“I’m fine,” she answers.

“You know that we’ll continue to talk and I’m not going to leave you hanging.”

“I know that.”

The two sit for a moment longer before White stands up. She gives him a hug and he leaves the house.

White’s children do not attend Cleveland Public Schools, which, though improving since White took control of the school board in 1998, still rank 545th out of the 549 school districts in Ohio (Dayton is the only big city that fared worse), according to 1999-2000 performance standards released by the Ohio Department of Education. The hope is to gain momentum, especially with the infusion of $380 million from the bond issue that s passed May 8 and with the continued leadership of Byrd-Bennett.

But nothing is a given. Byrd-Bennett’s contract expires in 2002, with an option to extend it to 2004. Whether she renews in 2002 will be depend, to some extent, on who the next mayor of Cleveland is. “It’s such a partnership ” she explains, “such a strong relationship that you have to have.” There is much at stake. According to the agreement that gave Cleveland’s mayor power to appoint the school board, voters will have an opportunity in 2002 to either axe the arrangement or approve it indefinitely. Byrd-Bennett, who strongly supports appointed, not elected, school boards, says White’s successor will play a big part in the 2002 vote.

“Whoever is the next mayor will have to clearly make some decisions about whether they support this system of governance,” she says.

White’s faith in Byrd-Bennett has always been absolute. Later that day, he tells a room packed full of people at his announcement: “If this is not Barbara Byrd-Bennett’s last job, something is wrong with us.” From the driveway of Byrd-Bennett’s house, White calls his two youngest children from an earlier marriage at home — 8-year-old Joshua and 11-year-old Brieanna. His fourth wife, JoAnn, has two children from a previous marriage — 22-year-old Katy and 24-year-old Christopher — whom White considers his own. The older children were told about the announcement the night before, but White decided to wait till the morning to tell the little ones.

The news, he says later, “Didn’t really sink in.”

“When you’re 8 and 11, you don’t quite really know what it means when your father’s the mayor. For all their life, I’ve been the mayor.”

Back home shortly after 7 a.m., White joins his staff and continues to execute his plan. With a list of 45 names and phone numbers in front of him — all people he wants to tell himself before his 10 a.m. announcement — he starts dialing.

Using his home phone and two cell phones, he works the lines with help from his staff, ending one conversation and immediately beginning the next. He calls former staffers who have remained on good terms, the few council members he still counts as allies, old friends and the loyal few who helped him win in •89.

One of his friends is on his tractor when White calls. Another hears wrong and begins to congratulate him. Others scream into the phone, begging him to reconsider. On the way to make his announcement at Glenville’s Miles Stan-dish Elementary School — his former grade school — he’s still making calls,

“I had used a fairly laborious, time-consuming and complex process of getting to my decision,” White explains in an interview held three weeks later at Voinovich Park. “I’m the kind of person … when I get to my decision, I’m very relaxed and calm about the decision.”

After graduating from The Ohio State University, White got a job working as a housing aid for then-Columbus mayor Tom Moody. He used the experience as a learning tool, not a steppingstone to a better job in a city that wasn’t his own. “Some people are willing to succeed anywhere,” says Jerry Gafford, then chief of staff for Moody. “Mike wanted his achievements to be in Cleveland.

“He always kept telling me that sooner or later he was going to have to go home to Cleveland. It was very much on his mind,” remembers Gafford, who tried to convince the young man to stay in Columbus. “He came in one day and said, •I’m leaving now. Don’t try to stop me. I’ve got to go, Jerry. I’ve got to go home.’ ”

White returned to Cleveland in 1976, serving first as an assistant to then-council president George Forbes, then winning a council seat himself. In 1988, he decided to chase what he calls “the only job I ever wanted.”

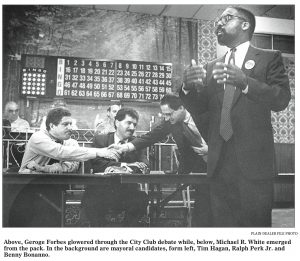

The mayoral campaign started out promisingly — White’s East Boulevard home was packed full of supporters during strategy sessions — but when then-mayor George Voinovich announced he would not run for re-election, a slate of strong contenders joined the race, including Forbes.

“All of a sudden, Mike’s support disappeared,” remembers state Sen. Eric Fingerhut, White’s campaign manager at the time. “It went from people being jammed in his basement to four or five of us.” By the time he made his official announcement, his supporters were so few that one of White’s staffers recruited her father and some of her friends to create the illusion of an audience.

But White has always been deft at dodging the odds. As an underdog for student-body president at Ohio State University, his campaigning cut short by a serious case of the chicken pox, he nonetheless won the election — with the slogan “Give a shit.” (He followed his own advice, becoming so enraged at one meeting that he allegedly threw a gavel across the room.)

That same doggedness propelled White above the pack in 1989. He went door to door, hosted teas and got up early to ride buses all morning with commuters — whatever it took. If he had a free minute, he’d find a grocery store and campaign there. “His one-on-one connection with people is just excellent,” Fingerhut says. “It was one of the great grass-root campaigns. You just knew he was going to be the next mayor.”

It’s almost 10 a.m. and a room full of people wait in the auditorium of Miles Standish. White’s father and wife are in the first row and the audience is packed with directors, cabinet members and staffers. A few Cleveland powerhouses — Greater Cleveland Growth Association CEO Dennis Eckart, Byrd-Bennett and former Rep. Louis Stokes — dot the audience, but elected officials are scarce; councilman Zachary Reed suspects he is the only office-holding politician in attendance.

Outside the school, Plain Dealer politics reporter Mark Naymik tries to enter, but the door is locked. He bangs on the door; no one answers. Finally, he makes his way inside through an unlocked classroom, taking a place among members of White’s administration sitting in the seventh row. But White’s scorn for the PD infects even this occasion.

“You can’t be here,” one of White’s people tells Naymik. “This is a private affair.”

“I’m not going anywhere,” Naymik responds. “Do what you have to do.”

Naymik eventually agrees to go outside to talk and is never let back in, despite the fact that it’s a public building and every other media outlet has been invited by the mayor’s office. (Naymik found out about the meeting from metro editor Mark Russell, who heard the news on the radio while driving to work.)

Naymik is outside the building when White takes the podium, following an introduction by Louis Stokes. White tells the audience he is “a child of Cleveland” and thanks a long list of people for their support over the years.

“I want you to know I love you all,” White tells the group. “I thank you for hat you have given me. I have given you Far less than you have given me. If I live to be 150 years old, I could never repay you t for what you have given me. You have given me an opportunity to serve. You have given me an understanding of life. You have given me a belief in humankind beyond what any of you could realize.”

White is scheduled to be at a Convention & Visitors Bureau lunch honoring him for his tourism efforts. Instead, he spends his lunch hour and early afternoon in the library behind the auditorium at Miles Standish, meeting first with family, then staff members.

A half-hour later, somewhere downtown, a separate meeting begins. (Dennis Eckart, CEO of the Greater Cleveland Growth Association, explains later that the group included a “very interesting collection of business and community leaders,” but he won’t say who and declines to say where.) The group had planned to discuss an economic-development initiative, but the agenda changed — without a single word or phone call exchanged — as soon as White made his announcement.

No one is late today; the gossip’s too good, the opportunity to speculate too tempting. “Were you there?” people ask each other. “What did you hear? Who’s running?”

For the past several months, Cleveland’s unofficial pundits — a loose alliance of business and community leaders — have been lamenting the breakdown of the public-private partnership in Cleveland. Chances are good that some of them are the same people in this room. The same people who were desperately searching for another candidate when it was assumed White would run again.

The same people White says he doesn’t much care to have as allies.

“My world may not be the Union Club and it may not be a golf course,” White explains later. “I may not be kissing every businessman’s ass who thinks I ought to kiss his ass. •Cause that’s not of my ilk. That’s not what I aspire to.”

Though White sometimes talks like a political lone ranger, Eckart says he’s found the mayor to be cooperative and accommodating. “I have asked, on behalf of the business community, a variety of things to move [airport negotiations] forward — a dozen difficult things for the city to do,” says Eckart, who describes his duty as being an “honest broker” between politicians and business leaders. “There is not one instance that the mayor said no.”

In fact, Eckart says he hasn’t seen White do anything to jeopardize the spirit of cooperation that led to Cleveland’s comeback. “I have no objective evidence at all of that in my personal relationship with the mayor,” he states.

But that doesn’t mean Eckart hasn’t heard the complaints. “I have talked to any number of other business folks who, 11 seconds into the conversation, would say, •Let me tell you about 1993,’ and recount some story about the mayor.” He even arranged to meet with one man, who had publicly complained about the mayor, to see if he could understand his perspective.

“I said, •When the mayor turned you down, what did you do?’ ” Eckart remembers.

“What was there for me to do?” the man shot back.

Plenty, is the answer Eckart most I commonly gives. Lobby City Council. Air your complaints to The Plain Dealer’s editorial board. Call the Growth Association. “The reality is that one entity — even if it is a very powerful entity — told you no and you quit. What does that tell me about your idea or about yourself?”

County commissioner Tim McCormack offers a more piercing assessment of what’s happened in Cleveland during the last few years. “People just left,” he says. “They just decided that it was not worth the aggravation.”

White seems untroubled by accusations that he has alienated people. “In my business, when things are going well, everybody is your friend,” he says. “But when things don’t go well, it’s an empty ballroom for one.”

He will not, however, divulge any names of those he feels have betrayed him. “I wouldn’t answer that question if you put a gun in my mouth,” he says.

***

At 4 p.m., editors from The Plain Dealer meet to discuss what will fill the front page of the next day’s paper — an easy task today, though the specifics must be hammered out.

“The field of candidates grows, I’m not kidding, by the minute,” city editor Jean Dubail tells the group.

In the hours following White’s announcement, a half-dozen potential candidates express interest in taking his place, including former Cuyahoga County child welfare director William Denihan; county commissioner Jane Campbell; councilmen Joe Cimperman, Bill Patmon and Mike O’Malley; and Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones, who will ultimately decide in early July not to run.

In order to show “maximum strength,” county commissioner Tim McCormack goes a step further. Just hours after the announcement, he stops by the board of elections to file petitions, followed by a visit to Plain Dealer editor Douglas Clifton. “McCormack clawed his way into Doug’s office to get a heads-up,” Dubail reports.

When another editor asks what White’s post-office plans are, Dubail replies: “He’s going to open a PR firm and be our adviser on public records.”

The joke provokes a few laughs, but White’s battle with the PD is a serious one, pitting First Amendment rights against allegations of libelous coverage. The paper has sued White over delayed — or nonexistent — access to public records. White claims the paper has intentionally tried to defame him.

The epic feud was played out in a single act earlier today: Incited by what he saw as a calculated attempt to annihilate his influence, the mayor of Cleveland banned a reporter from the city’s only daily paper from attending an announcement — held in a public building will change the course of the city.

The mayor does not dispute these facts. When asked if he believes it was a violation of Ohio’s open-meeting laws to kick Naymik out, he replies: “It doesn’t matter.”

He then launches into Mike White logic, which says that once you’ve been wronged, you have just cause to bend the rules. ” The Plain Dealer has willfully, purposely and premeditatedly tried to destroy the most important thing to me, which is my name and my integrity,” White says, gaining momentum. “They’ve done it with forethought and they’ve done it without an absence of malice. On the day I was announcing my retirement, they were not going to be in the room. I don’t apologize for it. I don’t believe I made an error. And if I had to do it again at this very moment, I’d throw him out again.”

Clifton, the PD’s editor, says his paper never targeted White. “My approach to editing a newspaper is that you give strong, assertive coverage of bodies of government,” he explains. “Whatever happens, happens.”

Though White’s office reportedly asked for extra copies of the May 24 newspaper. White will not say whether he was pleased or displeased with the article that ran. “They covered me,” he says stoically.

But was it fair coverage? “They covered me,” he repeats. White’s contempt for the paper is so intense that, later in the interview, he casually refers to Clifton as “Bushman.” Asked to clarify, he responds that anyone who hides in the bushes spying on people deserves such a name, topping his accusation off with, “And that’s for the record.”

Clifton explains that the reference stems from his days covering one time presidential hopeful Gary Hart. For the record, he adds, “There were no bushes,” and he has no nickname for the mayor.

White says he never had a problem with any other newspaper, but cannot provide an explanation as to why he’s having such a hard time with The Plain Dealer.

“This is a special case,” White says slowly, relishing the word “special” in a way that definitely suggests there’s some element of this combat he enjoys.

***

White sits in his office, turning his attention to the more mundane duties of the day. It’s past 5 p.m., but there are papers to sign, phone calls to return and legislative agreements to hammer out — seven months of work left to do.

The rest of City Hall is quiet. A few people stand talking just inside the main entrance, but the halls are largely deserted. Councilman Zachary Reed is the exception, moving silently through the building as he walks to his car to retrieve a briefcase.

It was seven hours ago that White announced his retirement, but the junior councilman is still dazed. “For me, not only is he a mentor of mine,” Reed says, then pauses as if struggling to regain his train of thought. “I’m still in shock … that’s why I can’t seem to get my words together. He’s not only a mentor of mine, but a friend.”

Reed was one of only four council members out of 21 whom White thanked during his speech earlier in the day. Council used to be much cozier with the mayor when Jay Westbrook was its leader, but a 1999 coup catapulted Mike Polensek to the position of council president. With the change in leadership, White’s control began to crumble, as did his relationship with Polensek.

Elected to council in the same year, 1977, Polensek and White once enjoyed the camaraderie that sprang from that connection. In fact, when White first ran for mayor in 1989, not only did Polensek work the polls, he also recruited his mother to help.

Two decades of politics devoured that friendship. In his retirement speech, White specifically thanked a total of 26 people — plus God — and acknowledged nearly a dozen others. Polensek was not mentioned. All of which makes the council president wonder if he made a mistake by campaigning for White so many years ago. “There have been times I asked myself, •Did I do the right thing?’ ” Polensek says.

He notes that the relationship has become “more cordial” since White announced he’ll be stepping down. “We’ve talked more in personal terms about our families,” Polensek says. “I have a little bit more insight into his perspective, which we had not talked about in the past.

“I’ve enjoyed it,” he adds. “You never really get to know [politicians] on a personal level. You always try to wear a hardened shell. You build up this reflective shield. You try to come across like you’re indestructible.”

But that doesn’t mean one can shed their armor completely before the battle is over. After talking about how he wishes White well and how “we are all God’s creatures,” Polensek sounds a subtle warning.

“My message has been: We have an opportunity to really focus in on the neighborhood projects, the reinvestment projects in our neighborhoods,” Polensek explains. “As I said to him in the mayor’s office as late as last week, this has got to be the priority. The next six months will tell the real story on Mike White.”

And if White doesn’t cooperate? “There could be some…” Polensek pauses, searching for the right words, “…differences of opinion.”

***

In his life after politics, White, who turns 50 this month, may be a consultant, a gentleman farmer, a professor or an author. He may raise llamas, help children or do nothing. He may live in Glenville or in Newcomers-town, where he and JoAnn have built a second home. He may travel to places his wife has recently visited, such as Israel and Thailand, or he may stay in Ohio.

All of the above have been speculated, but they are nothing more than guesses. The mayor’s not saying.

When asked what he plans to do next, he cuts the question short: “Haven’t the foggiest idea.”

What are the possibilities?

“There’s a period behind that,” he says, referring to his previous answer.

How does he think he’ll adapt to a slower pace?

“There’s a period behind that,” he snips. “I said, •Haven’t the foggiest idea and there’s a period behind that.’ ”

Will he still make Cleveland his primary residence?

“There’s a period behind that.”

A safe question: gardening. Does he see himself spending more time growing tomatoes? “There’s a period behind that.”

He will say not one word about his future. His voice rolls with passion, however, when talking about his past, especially about how he never sold the city or its residents out and how he feels he can leave office with a clear conscience.

“It’s not about just running till you die,” he explains. “The only thing I wanted to do was serve as mayor, and I’ve done that. And I’ve tried to do it as best I know how. I’ve tried to be as honest as I know how and I’ve always told the truth about it. Even when people didn’t want to hear the truth.

“This isn’t the real world,” he says, glancing at the Rock Hall and Browns Stadium from his perch in Voinovich Park. “The real world was at Luke Easter [Park] yesterday when I cut that ribbon and those little kids could get in a brand-new pool and they had a wading pool just like the suburbanites. The real world is being able to cut a ribbon at a new housing development. The real world is when kids are able to go to school and the glass isn’t falling and the heat isn’t off and a child in the 11th grade doesn’t have to put a coat on to take a test. That’s my world.”

On the night of May 23, White returns to his world at about 8 p.m. to spend a night like any other. On the way there, he passes his old elementary school; his father lives just a half mile away. By 11 p.m., the day has worn on him; his voice is hoarse and his objective accomplished.

The mayor closes his eyes and quickly falls asleep, ending his last day as a man with a political future. Or so he says.

Whether there’s a period behind that remains to be seen.