Fred Nance has crossed boundaries both real and symbolic

“See those boys on bicycles?”

Fred Nance, one of the region’s most powerful and influential citizens, eased his tan Escalade to a stop. He pointed at the trio of black boys pedaling furiously through an intersection near the Cleveland-Shaker Heights border.

Nance grinned and waved at the passing parade. They looked like city kids, not yet teenagers, racing home after a suburban adventure.

He didn’t know them, but he recognized them.

“There was me when I was their age,” Nance said. “That’s exactly what we used to do.”

His eyes followed as the boys disappeared into the streetscape, taking with them any chance to learn their past or witness their future.

“I used to ride my bicycle from East 135th Street and Kinsman, where we lived, to Shaker Heights,” he said. “I knew there was a different world than the one I saw every day in my neighborhood. I caught a glimpse of it, through the trees and across the lawns as I pedaled along South Park Boulevard, just like them.

“And I’d say to myself,” he continued in a low voice from a long-gone time, ” ‘Someday, I’m going to be a part of that world, too.’ “

Let the record show: Fred Nance has arrived.

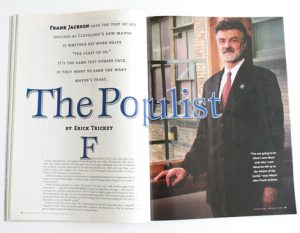

Regional managing partner at Cleveland-based Squire Sanders & Dempsey, one of the globe’s whitest-shoed law firms, Nance, 55, is a confidante to mayors and the go-to guy for nearly every civic project that’s come Cleveland’s way during the past two decades. He is one of this region’s most recognized and influential citizens.

That’s the public side. In private, Nance is one half of a civic-minded couple. His wife, the former Jacqueline Jones, heads the LeBron James Family Foundation, an Akron-based group that helps children and families in Northeast Ohio. Both husband and wife are high-profile attorneys.

Fred’s working-class childhood shaped his life. Jakki, as everyone calls her, grew up in comparative affluence. As a married couple, they complement each other. She’s the playful, outgoing and social counterpart to his more serious, studied and practical personality. Both are committed to improving the region.

Venturing beyond racial borders

Nance was set on his path during the long, violent summer of 1966.

In a social experiment that preceded Cleveland’s failed school-desegregation efforts, Jesuit priests recruited 12-year-old Nance to attend St. Ignatius High School on the near West Side.

“Even though I was far and away the best student at my inner-city grade school, I wasn’t deemed to be quite up to their standards,” Nance said. “So after I applied and was accepted to St. Ignatius, I had to take remedial classes that summer to get into the school in the fall.”

This was years before busing became the long-running court case that Nance would argue against on behalf of the Cleveland School District in federal courts. No, at this moment, Nance found himself waiting at the intersection of East 55th Street and Woodland Avenue for a bus to take him across the Cuyahoga River and the city’s racial borders of east and west, black and white.

For six days during that summer, rioters burned and looted in the Hough neighborhood after racially charged clashes between a white business owner and black customers. Young Fred watched in awe as National Guardsmen with fixed bayonets rode past in military halftracks on their way to engage the rioters.

“I watched guys come out of stores and smash the windshields of cars with sledgehammers and throw bricks through store windows,” Nance recalled. “I’m just a 12-year-old kid, standing on the corner and thinking: ‘There’s got to be a better way.’ I wanted to empower myself so that this wasn’t what I or the people I loved have to resort to.”

Right then, Nance made a promise to himself.

“I figured out, standing on that corner, that the advantages in life must go to the people who understand the rules of the game and who are in a position to manipulate them,” he said. “I decided then I wasn’t going to be a powerless victim, and I figured that being a lawyer was the way to go.”

He entered St. Ignatius that fall at the bottom of his academic class. Four years later, he graduated with an A average and rejected full scholarships to Princeton and Yale for one to Harvard.

“A lot of what followed for me happened as the result of the transition from one world to another that took place at St. Ignatius,” Nance said. “It wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t especially easy socially.”

After graduating from Harvard and the University of Michigan Law School, Nance returned to Cleveland in 1978, joining Squire Sanders & Dempsey as one of the few black associates at the firm. In 1987, he became a partner.

His life and career took a dramatic turn in 1991 when Cleveland Mayor Michael R. White needed a lawyer to represent him in a grand jury investigation. White wanted Charlie Clarke, then the dean of Squire Sanders trial attorneys.

White settled on Nance only after Clarke canceled appointments with the mayor and sent the young and promising black lawyer in his place. As Nance recalled, Clarke’s motive was to give him an opportunity that would promote his career. It worked to perfection.

“At first Mike wasn’t all that impressed with me,” Nance said. “But in time it clicked. He started asking me to work on different legal matters for him.”

Two years after that rocky start, White called Nance to ask him to negotiate a lease for him.

“I told him the only experience I had with that was signing a lease on an apartment when I was in law school,” Nance said, laughing at the memory. “He said just take care of this for me.”

The lease turned out to be the contract between the city and Art Modell, who wanted to move the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore. When the legal wrangling ended, the team had moved, but the city kept the Browns’ names and colors and the promise of a new team in 1999.

That legal work thrust Nance into the big time, and he bloomed as the go-to lawyer in Cleveland.

In the early 1990s, he was working on the busing case when he met Jakki. His first marriage had ended after 10 years. Jakki, too, was divorced and working for another law firm.

Their courtship is the stuff of family lore. Thrust together on the legal project, the two lawyers huddled over one-on-one lunches. Following each meeting, she billed him for her time. She was completely unaware that Nance scheduled the get-togethers to get to know her better.

Eventually, Nance came clean.

“Jakki,” he told her, “I keep asking you to lunch because I like you. And, would you please stop sending me these bills afterwards?”

Determination born of adversityJakki had a more privileged childhood than Nance, but a more stressful and dangerous one as well.

Her father is Dr. Jefferson Jones, a nationally recognized oral surgeon, who wanted nothing but the best for his two adopted children: Jeff and Jakki. The family lived in affluent white communities where they weren’t always welcome.

Jakki Nance, 42, remembers racial attacks and social ostracism that dogged her and her family as they integrated predominantly white neighborhoods and schools.

Vandals struck their home repeatedly when they moved into Pepper Pike. Someone broke the tops off three driveway light poles. The house was egged. Eventually, the night marauders fired shots into the house.

Jakki said it scared her, but not her father, who armed himself and refused to leave.

“He had been in the Army and was determined to protect his family,” she said. “As a child, I felt protected by my father even though I hated we had to go through all that.”

Her father wanted her to become a doctor, but she pursued dance before deciding to become a lawyer.

Her years at Orange High School were filled with confrontations with white teachers who doubted her intelligence and black and white classmates who shunned her. Only after leaving Ohio in 1984 to attend Spelman College, the predominantly black women’s school in Atlanta, did she find a sense of self and acceptance.

“At Spelman I was happy,” she said during a recent interview as she picked at a green salad on the patio of a suburban East Side restaurant. “It was the first time in my life I was judged on my work instead of who I was.”

Jones, now retired, said his daughter’s childhood experiences made her determined to succeed.

“She had the attitude that nothing would stop her from what she wanted, that she would show everybody what she was made of,” he said.

She returned to Cleveland after college and entered law school at Case Western Reserve University. By the early 1980s, she was working in a family friend’s law office and seeking ways to make a mark in the city.

She and Nance were married by White in 1999.

Jakki Nance has been instrumental in turning around the disorganized LeBron James Family Foundation. Under her direction, the foundation has formed closer ties with local businesses and created profitable projects like an annual bike ride for charity.

The couple agree that their lives far exceed anything they ever imagined as youngsters.

“I’m one of the luckiest people I know,” Fred Nance said. “But I believe you make your own luck. I always wanted to be successful, but I didn’t know what success would be or look like.”

When the National Football League needed a new commissioner a year ago, Nance’s name was on the short list.

John Wooten, chairman of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, a Washington, D.C.-based group that advocates for greater diversity in professional football, said the organization recommended Nance for the job because of his role in bringing a new team to Cleveland after Art Modell moved the Browns to Baltimore.

“Fred Nance was a guy who’s a great lawyer and we felt helped us save Cleveland and save the Browns for Cleveland,” said Wooten, who played on the Browns’ 1964 championship team.

While the couple toyed with the idea and enjoyed the attention, neither Fred nor Jakki was eager to leave their comfortable lives in Cleveland.

Currently, Nance is neck deep in negotiations to secure a Medical Mart/convention center as the curative to an ailing downtown.

Why is Nance the go-to guy on so many civic projects?

Tom Stanton, chairman of Squire Sanders & Dempsey, thinks it’s something simple, elemental and rare. “People trust him,” he said.

“It’s a chemical thing,” Stanton said, over coffee and dessert at a dinner party in Nance’s home for the firm’s summer associates. “I don’t know how to explain it, except to say he has this natural sense of empathy that compels people, and I mean everyone, blacks and whites, young and old, to be comfortable around him.”

<class=”caption”>The Fred Nance File

For nearly 30 years, Fred Nance has been involved in a battery of legal matters at Squire Sanders & Dempsey that defined and shaped Greater Cleveland. Here’s a partial list of some of his highest-profile cases and negotiations:

• 1979 — Carnival kickbacks — As a first-year associate, Nance joined the trial team that successfully represented George Forbes against accusations that the then-Cleveland city council president had accepted payoffs from a local carnival operator.

• 1991 — Doan and Beehive school projects — A county grand jury investigated whether then-Mayor Michael White had, as a councilman eight years earlier, used his position as a city councilman to aid the development of real estate projects in which he was an investor. White wanted the top trial lawyer in the city to represent him. Instead, the law firm sent Nance. The grand jury never charged White, and the two men became friends. For Nance, it was the start of a relationship and an entree to a series of lucrative legal contracts with the city.

• 1995 — Cleveland Browns — Nance represented the city in a lease dispute with Browns owner Art Modell, who was in the process of moving the team to Baltimore. The Browns were forced to delay their move and to leave all team colors, names and trademarks in Cleveland.

• 1991-96 — Busing — Nance represented the Cleveland School District, on behalf of White and a group of black community leaders, seeking to release the schools from court-ordered busing. After years of legal wrangling, a federal court ruled in 1996 to allow the district to assign pupils “with its best judgment rather than complying with a court-ordered mathematical formula for racial balance.”

• 1997 — Concourse D — Nance negotiated a 30-year lease of the new concourse with Continental Airlines, a $100 million investment that ensures Cleveland Hopkins International Airport remains a Continental hub.

• 2001– Brook Park land swap — Though many other attorneys were involved in the decade-long litigation over the controversial decision to swap land and municipal boundaries between Cleveland and Brook Park, Nance claims credit for settling the matter. The deal allowed construction of an extended runway at Hopkins.

• 2003 — The throwback jerseys — Nance had no clue who LeBron James was, but agreed to help the high school basketball player at the request of a friend. James faced suspension from the state championships because he accepted two vintage basketball jerseys worth about $845 from a clothing store. Nance won in court, allowing James to lead his team to the state title in his senior year. Nance’s wife now heads James’ foundation.

• 2005-2006 — DFAS — Nance led the successful effort to retain 1,100 jobs at the Defense Finance Accounting Services Center in Cleveland.

• 2007-present — Medical Mart — Nance spearheads the ongoing talks to develop a new convention center and medical mart in downtown Cleveland.

Plain Dealer News Researcher JoEllen Corrigan contributed to this report

</class=”caption”>

Comfort zone without boundariesThis is no small feat and, in large measure, is the real secret to Nance’s success. In a hyper-segregated, class-stratified city, where East rarely meets West and wary tribes mingle at arm’s length, Nance is expert at crossing boundaries.

Or, to put it another way, Nance never lost the feeling of freedom, just like the carefree boys on bicycles, that comes with racing across the sharp and bright lines dividing one part of Cleveland from another.

To that end, he added, it’s important that he and other black professionals hold themselves up as examples.

“If you don’t see people who look like you, people who started out where you started out, it is not an irrational conclusion to draw that it is impossible to try and work within the system,” Nance said. “That’s why it’s very important to show African-Americans who have done things right and are enjoying the benefits.”

Nance makes crossing boundaries appear effortless and perfectly natural. To watch him work a room — whether at an all-black social gathering, a racially mixed civic meeting or formal presentation where he’s the only African-American — is like watching a skilled athlete going through practiced repetitions.

“My forte is dealing with difficult people in stressful circumstances to come out with a positive result,” he said.

None of this is easy. Years of preparation and practice — along with setbacks and miscues — precede the performances that make fans cheer and detractors jeer.

And he does have detractors. Though few of them are willing to say so out loud or in public.

“I’m so sick of hearing about him,” said one black Cleveland attorney, who admitted to being more than a little envious of the glowing media attention that sticks like cellophane to Nance. “He’s a good lawyer, but there are so few of us out here and he’s like the only one that everybody knows and talks about. That can get to be old and a bit too much to swallow.”

Nance has heard such talk.

“People don’t say that to my face, but they say it around mutual friends, and it gets back to me,” he said, adding there are others who say even worse. “Then, there’s a group that says I’m a tool of the establishment, just like every other fat cat profiteering off the backs of the people.”

After recounting these critical comments, Nance laughed and said there might be a bit of truth to them.

“It’s obviously ironic to me, given where I started,” he said, still chuckling. “Maybe, it’s deserved because I certainly have benefited from being a part of the system. But I honestly believe I’ve had the opportunity to do the public good that I’ve always dreamed of and I have a good life, too. It’s the best of both worlds.”

Nance recently joined a dozen professional black men on a stage at Audubon School, a public elementary school not far from his old neighborhood. One by one, the men — doctors, engineers, college professors and lawyers — described their occupations to the kids, who sat in wide-eyed wonder at the idea of people who look like them doing unimaginable things.

When his turn arrived, Nance spoke without a microphone, projecting his deep voice to the back of the auditorium.

“I was raised right around the corner from here, at 135th and Kinsman, and I’m a lawyer,” Nance said. “I represent a young man you all know named LeBron James . . . “

Nance paused for dramatic effect, as the kids perked up at the name of the famous basketball star.

“I’m here today because I need one of you to come and take my place one day.”

The auditorium exploded in cheers as the kids stood to applaud. And Nance, beaming just as he had when the boys on the bicycles crossed his path, crossed yet another boundary, pressing his own childhood dreams onto the next generation.