Neighbors Then Strangers: African American-Jewish Postwar Interactions 1950-1970

by John Baden

Various forces shaped where African Americans were able to reside in northern industrial cities like Cleveland during the first half of the twentieth century. Racist housing deeds, real estate practices, and violent intimidation forced most African Americans in Cleveland to live in only a handful of neighborhoods. These neighborhoods, however, were not particularly segregated prior to the 1950s. Residents attended the same schools, shopped in the same stores, and lived in a remarkably diverse community. Ironically, historically African American neighborhoods in Cleveland became homogenous, and more segregated during the civil rights era, a time associated with progress towards integration. Despite efforts to empower African Americans to reside in a neighborhood of their choice, inner city African Americans found themselves more segregated than ever. To understand why inner-city neighborhoods like Cleveland’s Central became increasingly segregated during the civil rights era, it is important to investigate why whites stopped living and working near African Americans, as many had done in the past.

This essay will address these issues by discussing the decline of community interactions between African Americans and Jews from 1945 to 1970 in the city of Cleveland, Ohio. These interactions give us some understanding of the process of neighborhood transformation because Jews and Africans often lived in the same areas throughout the early twentieth century. Moreover, Jews who retained business in the neighborhood continued to play important roles in the community for several decades. As time passed, though, fewer Jews had a presence in these neighborhoods, and these spaces became more homogenously African American. As a result, African American Jewish interactions waned in Cleveland proper (although some significant interactions continue in the suburbs).

One should not dismiss the civil rights movement or wax nostalgic about earlier ethnic relations; opportunity has risen for most African Americans, and about half now live in suburbs.[1] Still, inner-city African Americans that made up what sociologist William Julius Wilson called “the truly disadvantaged” in industrial cities like Cleveland, however, often lived more isolated lives than ever between 1950 and 1970.[2]

One of the most important communities examined for this study is Central, a neighborhood located just east of downtown Cleveland. As discussed in the first segment, from roughly 1900 to 1920, the neighborhood was the heart of the city’s African American and Jewish community. But these communities only comprised part of the neighborhood’s diversity. It was also home to Big Italy and other ethnic groups as well.[3] African Americans and Jews interacted with one of another in many different spheres, and by no means lived isolated lives. Even after most Jews moved out, many Jews held onto businesses in the area. For example, in 1930, 46.5 to 58.1 percent of grocers on Central Avenue were Jewish even though nearly all Jews had moved out of the area.[4] Thus African Americans often worked and shopped in Jewish-owned businesses.

After Congress passed immigration restrictions in the 1920s, hardly any new European immigrants moved into Central. Instead, their places were filled by African American migrants from the South. Cleveland’s African American population increased from 8,448 in 1910 to 34,451 in 1920, and then 71,899 in 1930.[5] As whites’ views hardened about the desirability of segregation after World War I, it became nearly impossible for African Americans to live outside of Central or a select few small communities, which were usually also located near Jewish populations.[6] As a result, the Central neighborhood became increasingly African American and segregated.

This, however, did not need to be permanent. World War II provided an opportunity to re-integrate Cleveland neighborhoods. Americans frequently invoked the wartime rhetoric of democracy and a battle against racial supremacy during World War II, which could have spurred changes in attitudes and laws. Cities like Cleveland could have been an asylum for the refugees of World War II and the Holocaust. Instead, segregation remained as harsh as ever, and immigration restrictions largely prevented Jews and other Europeans immigrants from fleeing to the United States during the Nazi and Stalin eras. These refugees and displaced people could have helped maintain a racial balance in old immigrant neighborhoods. Instead, white ethnics and African Americans would live further apart in areas more isolated from each other.

By 1950, most of Cleveland’s 148,000 African Americans in 1950 still had little ability to live anywhere but Central. Most African Americans were relegated to the lowest paying jobs in a given industry, and often had the lowest seniority. White home owners often refused to sell to African Americans, and African Americans who managed to find a home in a new neighborhood were often violently harassed by whites.[7]

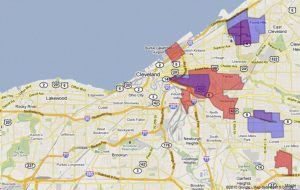

It was extremely rare, however, for Jewish Americans to violently resist African Americans moving in, and Jews even gained a reputation for selling or renting property to African Americans.[8] As the Association for Jewish Communal Relations’ president, Sidney Vincent, commented in 1962, a “substantial share of housing in the Negro area-with all the attendant irritation-is owned by Jews, partly because the neighborhoods are largely formerly Jewish,” and observed that when blacks did move to suburbs, “in almost every case, it has been a leap into a Jewish neighborhood.”[9] One disgruntled white opponent of integration complained, “the Negro follows the Jews in housing; no Jews, no Negroes to follow.”[10] This ensured that African Americans and Jews would have a measure of interactions with one another in these newly opened up neighborhoods for decades to come. Yet, prejudice would continue to affect the scope and form of these interactions.

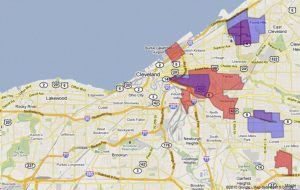

Figure 3 Previously Jewish neighborhoods are shaded in blue, and compared to African American neighborhoods in 1950.[11]

Unfortunately, after African Americans moved into their neighborhood in substantial numbers, many Jewish residents (like other European ethnic groups) moved out almost immediately. For example, Glenville, a neighborhood just north of University Circle, went from being predominately Jewish (over 70 percent in 1936) and over 90 percent white in 1940 to nearly 50 percent African American in 1950, and predominantly African American by 1960.[12] Unfortunately, after a neighborhood transitioned to a predominately African American one, few whites wanted to live in it. Thus, demand for that housing decreased after most whites no longer wanted to live there. As a result, African Americans often saw little or no equity gains once they bought a house in a previously white neighborhood because area-wide demand for housing in the neighborhood would plummet. Indeed, the falling value of a house in an integrating neighborhood convinced many whites to leave.[13] Without equity, banks were hesitant to extend credit to property owners, thus exacerbating the wealth gap between African Americans and whites. Reporting in fall of 1950, a Call & Post team headed by Marty Richardson wrote that in the area between Ashbury and Parkwood to St. Clair and East 99th in Glenville, over twenty churches along with five synagogues “have either recently been sold to Negro congregations, are reportedly or actually for sale,” and a building on Kimberly Avenue “that would cost more than a half-million dollars to build…is reportedly on sale for $75,000.”[14]

It should be noted that not everyone who moved to a suburb did so because of racial anxieties. There were many advantages of moving to a suburb like better funded school districts and more space to live in. Moreover, the federal government’s support of highways and segregated suburban neighborhoods at the time, made suburbs a feasible, if not more economical option.[15] Furthermore, many people enjoyed higher incomes in the post-war economy and were able to buy a nicer home in a new neighborhood. White departure from the largely working-class Jewish sections of the Kinsman neighborhood was much slower, and harder to classify as “white flight.”[16] Indeed many more affluent African Americans have moved to the suburbs as well.

Regardless of motivation, though, white departure contributed to a more segregated city. Before long, African Americans in Glenville, and eventually Kinsman, found themselves in neighborhoods as segregated and deprived of capital as their previous residences. As a result, African American–Jewish interactions in places like Glenville would largely be between residents and business owners, rather than as neighbors.

Since many of the neighborhoods’ African Americans lived in had once been Jewish communities, there were a disproportionate number of Jewish-operated businesses there. Determining the number of Jewish-owned businesses in African American neighborhoods during the 1950s and 60s is difficult. According to a 1968 government study of “ghetto” businesses in fifteen non-Southern cities, 39 percent of “ghetto merchants” (52 percent of white merchants) were Jewish, although the number in Cleveland was probably higher due to the intense overlapping of African American and previously Jewish neighborhoods. Since the study was taken after most of the nation’s urban unrest, the percentage of Jewish owned stores was probably higher in the years immediately preceding these events.[17]

The presence of so many white and often Jewish-owned businesses in now predominately African American neighborhoods caused consternation among some of its African American residents.[18] New York-based African American intellectual James Baldwin voiced these concerns by writing,

“It is bitter to watch the Jewish storekeeper locking up his store for the night…with your money in his pocket, to a clean neighborhood, miles from you, which you will not be allowed to enter.”[19]

Such occurrences were reminders of how racism picked who could succeed and who could live where. The point is particularly poignant, because where one lives in the United States has often increased one’s chances of succeeding. Yet, Baldwin’s latter point seems a bit reductionist given that many Jews, at least in Cleveland, did sell their homes to African Americans, and participated in suburban integration efforts in places like Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights.[20]

On top of being perceived as “outsiders,” non-African American store owners faced criticism for high prices. According to a supplemental study for the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, prices were in fact higher in African American neighborhoods in the North than other neighborhoods. This was because it was risky to operate a business that relied on impoverished residents who had to purchase goods through installment plans or on credit.[21] As a result, prices had to be high to account for the losses incurred by customers who were unable to finish their payment plans. Moreover, it was much more difficult for small independent stores to buy at discounted bulk volumes from suppliers. Nevertheless, these high prices were a source of frustration for customers who were often hard-pressed for cash.

African Americans did not universally condemn Jewish businesspeople that had a large African American clientele. As mentioned in first segment, some African Americans had positive experiences working in Jewish-ran stores. Moreover, figures like the disc jockey Alan Freed won a large devoted African American audience. Former Cleveland resident, W. Allen Taylor, who worked at both an Italian and Jewish-owned grocery store in the mainly middle-class Lee-Harvard area, recalled that

“There was some tension, especially during the mid to late sixties as black folks became more vocal about their demands for respect. For the most part, however, the Jewish retailers who maintained a presence in my mostly black neighborhood, understood how to relate to black folks with a minimum of tension, so it was fairly peaceful.”[22]

Conversely many notable African Americans found significant Jewish support. The most notable of these was Mayor Carl B. Stokes, who became the first African American elected mayor of a major city in 1967. Since most Jews no longer lived in Cleveland, they were not a significant part of his voting coalition. However, a number of Jewish Americans supported his campaign.[23] Marvin Chernoff, for example, was a key volunteer organizer on the campaign who helped put together Stokes’ impressive grassroots network. In the preface of his 1968 book, Black Victory, Jewish-American Kenneth G. Weinberg (who was from the Cleveland area) expressed the hope that many white intellectuals and businessmen held for a Stokes mayoralty.

“The significance of the election of a Carl Stokes lies elsewhere. He has, for the time being at least, demonstrated that black political activity can provide a viable alternative to violence in our cities… ‘The Fire Next Time’ has become a prophecy fulfilled, and the mind reels under shrill cries of separatism, nationalism, Malcom Xism, and a sad prediction by the President of the United States that our cities will almost surely experience several more summers of violence.”[24]

Thus, to Weinberg and others, encouraging African American municipal leadership was both good policy, and good for business.

The same could be said for many of the attempts to integrate Cleveland’s businesses. It was the right thing to do, but also expanded one’s customer base. Cleveland’s nightclub scene provided one of the most dramatic attempts at integration. A number of the key nightclubs in these integration efforts were owned by Jewish businessmen. One club, the Jewish-owned nightclub, Leo’s Casino, so thoroughly integrated that comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, called it, “the most fully integrated nightclub in America.”[25] This club, however, was located in heavily African American or transitioning sections of town.[26] Nightclubs that welcomed African Americans in the traditionally exclusive University Circle area met far more resistance.[27] In March of 1952, a bomb exploded at the Towne Casino, an integrated nightclub located near University Circle. Although a perpetrator was never found, it was widely believed that opponents of integration were responsible.[28] The club closed after two additional bombings.[29] Another nearby Jewish-owned nightclub, Playbar, was also forced to close after liquor board harassment and a bombing.[30] These events and other racially motivated bombings across the city helped bifurcate the city’s neighborhoods and commercial districts into either predominately African American or white.

Jewish owned business in African American neighborhoods faced an increasingly difficult climate for doing business in the 1960s. Business owners faced competition from chain stores, and crime rose during the decade in nearly every category.[31] Moreover, urban unrest broke out in Hough in 1966 and 1968 in the Glenville neighborhood which damaged 63 businesses and left surviving white-owned business in a precarious state.[32] After the unrest in Glenville, the neighborhood’s main commercial artery of Glenville went from having twenty-two grocery stores in 1966, to fourteen in 1971, a 37 percent loss.[33]

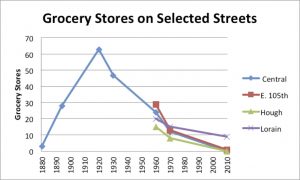

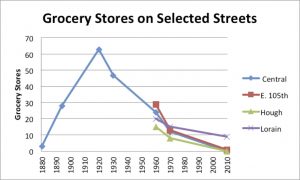

Table 2 This graph shows the decline of inner-city grocery stores on selected roads. It should be noted, though, that the 2010 Yellow Book does not appear to include most convenience stores as grocers. Also, Lorain is a longer street than the other mentioned streets, and a portion of Hough Avenue changed its name. Still, one can see an overall pattern.[34]

Crime, white flight, unrest, and racism, however, are only some of the reasons for the disappearance of white-owned businesses. Many businesses closed because Jewish families were able to enter different professions and work in different locations. Many Jewish grocers who grew up in Glenville during the 1930s and 40s retired in the post war years. Their children were often raised in more affluent households than their parents, and preferred to enter into other vocations or to work in other neighborhoods.[35] Furthermore, one large chain store could encompass the services of many small independent grocery stores for lower prices. Even before the fore-mentioned social turmoil of the 1960s and 70s, the number of grocery stores on Central Avenue, the historical center of Cleveland’s African American community declined from forty-three in 1930, to twenty-four in 1960.[36] Thus, we can say that the era of Jewish-owned small businesses in African American neighborhoods was already coming to an end, but that urban unrest, chain-stores, and higher crime rates during this time period expedited this process.

Examining the rise and fall of Jewish interactions with African Americans in inner-city neighborhoods gives perspective into how African American neighborhoods like Central and Glenville have become so predominantly African American and devoid of many white-owned businesses. Any number of events could have prevented the segregation, or re-segregation of Cleveland neighborhoods. Had the United States been a safe-haven for migrants during the World War II era, had there not been so many bombings to enforce the color line, had crime not been so high during the 60s and 70s, or had African Americans been able to live where they could afford and wished to live, Cleveland’s neighborhoods would have looked very different. Despite recent progress in integrating Cleveland’s West Side and East Side suburbs, many of Cleveland’s historically African American neighborhoods remain highly segregated, and devoid of much capital, businesses, and opportunity.

[2] William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, Second Edition (University of Chicago Press, 2012). See also Douglas S. Massey, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Harvard University Press, 1993)

[4] This estimation is based off entering the names of grocers listed on Central Avenue in the 1930 Cleveland City Directory into a necrology search on the Cleveland Public Library to determine where they were buried.

Cleveland Directory Co., Cleveland City Directory [microfilm], (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications). Cleveland Public Library, “Cleveland Necrology File,” Cleveland Public Library, http://www.cpl.org/necrology.

[5] Kenneth L. Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870-1930 (University of Illinois Press, 1978), 10.

[6] For a discussion on hardened attitudes on segregation, see ibid..

[7] Sidney Z. Vicent, “MEMORANDUM ON HOUSING SITUATION, LEE-HARVARD AREA,” in Remembering: Cleveland’s Jewish Voices, ed. Sally Wertheim & Alan Bennett (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2011 (citation taken from manuscript copy). Probably the best source of examining bombings against African Americans is a proquest search for “bomb” in the ProQuest Historical Newspaper: Cleveland Call and Post (1934-1991), accessed 2010, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy2.cpl.org/hnpclevelandcallpost/index?accountid=1810 and Cleveland Call & Post, and “Bombs,” Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio. Discussions of this issue in other cities can be found in Arnold R. Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago 1940-1960 (University of Chicago Press, 2009). David M. P Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). Douglas S. Massey, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Harvard University Press, 1993).

[8] Sidney Z. Vicent, “MEMORANDUM ON HOUSING SITUATION, LEE-HARVARD AREA.” Sidney Z. Vincent in Eugene J Lipman, A Tale of Ten Cities; the Triple Ghetto in American Religious Life. (Union of American Hebrew Congregations.) ,1962 John Baden, “Residual Neighbors: Jewish-African American Interaction in Cleveland from 1900 to 1970” (master’s thesis, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, 2010). This issue in Boston is discussed in Gerald Gamm, Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed (Harvard University Press, 2001).

[9] Vincent, A Tale of Ten Cities; the Triple Ghetto in American Religious Life, 58.

[11] Donald Levy, 24., Howard Whipple Green, Jewish Families in Greater Cleveland (Cleveland: Cleveland Health Council, 1939) and Socialexplorer, “1950 County and Census Tract,” Socialexplorer, http://www.socialexplorer.com/pub/maps/map3.aspx?&g=0. “Google Maps,” Google Maps, accessed October 16, 2010, https://www.google.com/maps/.

[12] Rubinstein and Avner, 111. Marty Richardson, “Sweeping Population Shift Hits Glenville Churches Hard: Falling Congregations Close Up Many Institutions; Values Drop,” Cleveland Call and Post, September 2, 1950, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009), Socialexplorer, “1960 County and Census Tract,” Socialexplorer.

[13] This issue in Detroit is discussed in David M. P Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America.

[14] Marty Richardson, “Sweeping Population Shift Hits Glenville Churches Hard: Falling Congregations Close Up Many Institutions; Values Drop,” Cleveland Call and Post, September 2, 1950, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009).

[15] Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford University Press, 1985); Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000 (Random House LLC, 2009); Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2010).

[16] For a discussion of neighborhood transition in this area, see Michney, Todd Michael, “Changing Neighborhoods: Race and Upward Mobility in Southeast Cleveland, 1930-1980,” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2004).

[17] The percentage of Jewish-owned businesses in these neighborhoods was probably higher because most African American businesses were not targeted during the riots; meaning that their percentage probably went up, while the percentage of non-African American businesses went down.

[18] Determined by entering names of grocers in Central from 1930 into a search of Ancestry.com, 1910-1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line] (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009).

[20] Charles Bromley, Interview by author, Cleveland, OH, July 2009.

[21] National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, New York Times ed. (New York: Bantam Books, 1968), 275-276.

[22] W. Allen Taylor interview, interview by author, email, March 2010.

[23] Robert Gries, interview by author, phone, November 2014.

[24] Kenneth G Weinberg, Black Victory; Carl Stokes and the Winning of Cleveland (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1968), 8.

[26] Leo’s Casino was located in the heavily African American Central district before moving to the Hough/Fairfax district which as transitioning into a predominantly African American area. Ibid., Socialexplorer, “1960 County and 1970 Census Tract,” Socialexplorer, http://www.socialexplorer.com/pub/maps/map3.aspx?&g=0.

[27] One such club was the Towne Casino, located near Euclid and East 105th street and owned by Jack Rogoff and Edward Helstein. Rogoff, like Leo Mintz, had grown up in a racially mixed block in Central, before moving to Glenville.

[28] Howard Drechsler, interview by author, notes, Beachwood, OH, August 2009.

[29] John Fuster, “Tips FOR THOSE INTERESTED N ENTERTAINMENT,” Cleveland Call and Post (1934-1962), August 8, 1953, sec. B, proquesr.com

[30] “RAIDED! Black and Tan Club Charges Persecution,” Cleveland Call and Post, May 16, 1953, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed November 18, 2009). “Tips FOR THOSE INTERESTED IN: =ENTERTAINMENT=,” Cleveland Call and Post (1934-1962), August 22, 1953, sec. B, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy2.cpl.org/hnpclevelandcallpost/docview/184249208/abstract/AC99276D1D3A422DPQ/1?accountid=1810.

[33] Cleveland Directory Co., Cleveland City Directory [microfilm], (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications).

[34] Ibid. For 2010, Yellowbook, Cleveland: Greater Cuyahoga County Area (Yellow Book Sales Distribution Company, Inc., 2010). Note that Yellow Book does not appear to include most convenience stores as grocers.

[35] Bill Rogoff, interview by author, notes, phone-call, March 2010.

[36]Cleveland Directory Co., Cleveland City Directory [microfilm], (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications)., (Cleveland: Cleveland Public Library, Preservation Office, 1990).