| 1 | City Manager Plan from the Cleveland Encyclopedia of History |

| 2 | City Manager Plan A Flop – Plain Dealer July 26, 1968 |

Category: City Managers Political Bosses 1920’s

Fred Kohler aggregation

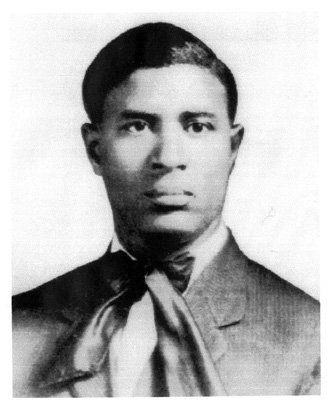

Inventor Garrett Morgan, Cleveland’s Fierce Bootstrapper by Margaret Bernstein

Ohio Historical Society Photo

INVENTOR GARRETT MORGAN,

CLEVELAND’S FIERCE BOOTSTRAPPER

By Margaret Bernstein

Garrett Morgan was a boundary-pusher and a status-quo smasher.

The son of Kentucky slaves, he moved to Cleveland in 1895, where he would become one of Ohio’s most prolific inventors. His curious mind seemed to crank at breakneck speed at all times, ferreting out problems that needed to be solved and providing the creative spark for his many inventions.

But neither Cleveland nor the nation were ready for a black man operating on such an entrepreneurial level in the early 1900s.

Just like he invented many “firsts,” Morgan himself was a first in many ways as he tried to insert himself and his inventions into the economic mainstream. And as a result, he collided repeatedly with social mores that for centuries had kept blacks in their place.

Persevering in the face of barriers and professional slights, he learned to navigate his way within the tightly segregated confines of 20th century America, although it sometimes meant he had to disguise his race in order to sell his products.

Morgan designed many items, including two life-saving devices – a gas mask that helped firefighters and soldiers survive in suffocating circumstances, and a traffic signal that restored order to intersections that had become chaotic and dangerous after the advent of the automobile.

He even invented institutions that helped nurture Cleveland’s fledgling black middle class. Once Morgan’s products earned him enough income to support his family, he started up a black newspaper, a black businessman’s league and even a black country club.

Decades after his death, it’s not unusual for this black Clevelander to be mentioned prominently during Black History Month, always a time when the achievements of African-Americans are listed and lauded across the nation.

Today he is recognized in his adopted hometown as well. Cleveland has a school, a waterworks plant and a neighborhood square named for the famed African-American inventor.

But these accolades arrived long after he could enjoy them. Although he eventually earned enough to live off his inventions and enjoyed a standard of living experienced by few blacks, he always felt blocked by barriers placed on him because of his race.

——————————

Garrett Augustus Morgan was born in Kentucky on March 4, 1877, the seventh of 11 children.

His parents, both of mixed parentage, had been slaves before the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

His father, Sidney Morgan, was the child of a female slave and a Confederate colonel, John Hunt Morgan. But Sidney Morgan’s father was also his family’s slave owner, and as a result the child suffered great physical abuse from his owners. History books show that this was a common plight for mulatto slaves – their owners would treat them cruelly since they were the physical reminders of an indiscretion on the part of a white man.

“Morgan’s father shared stories of the cruelty and abuse he had suffered, and sought to teach his son about the racial prejudices he would surely have to face in the world,” according to a detailed biographical essay on Morgan that appeared in a 1991 issue of Renaissance magazine.

His mother, Eliza Morgan, was half-Indian and half-black, and reportedly received her maiden name from her slave master. Her father, a Baptist minister, was a spiritual and law-abiding man. His deep and abiding faith would go on to have a big influence in Garrett’s life, giving him patience when he found doors to opportunity slamming in his face.

Young Garrett Morgan attended elementary school in Kentucky and worked on his parents’ farm.

It was a brutal time in Morgan’s native Kentucky, which was still reeling with resentments caused by the abolition of slavery. Lynchings of black men happened frequently in the 1880s and 1890s. Garrett Morgan showed the ambition and independent nature that eventually would make him a wealthy man when he decided, as a teen, that he would leave his family to head north.

At age 14, he arrived in Cincinnati with just a few cents in his pocket. He got a job as a handyman for a white property owner.

Morgan had only attained a fifth grade education while growing up in Claysville, Ky. “He knew how to read. He could write and he could figure,” said his granddaughter, Sandra Morgan of Cleveland, in a 2012 interview.

“But he had higher expectations for himself,” she added. And so he used his earnings as a young teen to hire personal tutors to teach him English and grammar. These competencies, he hoped, would help him get ahead.

Yet young Garrett found that Cincinnati’s racial dynamics did not seem much different from the Jim Crow restrictions of the deep South. A few scattered lynchings had been reported in southern Ohio too, during the years Morgan lived there.

And so he decided to move on. Cleveland seemed as good a place as any to land, since Morgan had some relatives in northern Ohio. He packed up his things and arrived in the area on June 17, 1895. He was one of the earlier blacks to migrate to the area. In 1890, just over 3,000 blacks had been recorded in Cuyahoga County.

Taking a room in a Central Avenue boarding house, Morgan began looking for work. According to Renaissance magazine, his enthusiasm was doused quickly, as he was told over and over, “We don’t employ niggers here.”

He eventually landed a job sweeping floors at Roots & McBride, a sewing machine factory, earning $5 a week. The youth proved to be a quick study, and he had a strong work ethic. He taught himself to sew and to repair sewing machines, and soon started working as a repairman.

Roots & McBride became the setting where his inventor’s spirit took root, and Morgan soon created his first invention — a belt fastener for sewing machines. He sold the idea in 1901 for $150.

In 1907, the Prince-Wolf Company hired him to be their first black machinist. There he met an immigrant seamstress from Bavaria, Mary Hasek. “They would engage in innocent conversations, until Morgan was warned by his supervisor that black men were not allowed to talk to white women in the company. Incensed at being told who he could and could not speak to because of his color, Morgan went to the Personnel Office and quit,” according to Renaissance magazine.

Morgan had been saving his money for years, with a goal of being his own boss. This was the moment, he realized. Using his savings, he rented a building on West Sixth Street and opened a sewing machine repair shop. It was just a few blocks from the Prince-Wolf Co.

These were tough times for African-Americans, but Morgan vowed to make his business a success. He was known to have a motto: “If a man puts something to block your way, the first time you go around it, the second time you go over it, and the third time you go through it.”

While building his business, he also worked hard at another goal: pursuing the seamstress who had caught his eye, Mary Hasek. Although her family refused to accept the interracial relationship, Mary had an independent streak herself and she fell in love with her outgoing and ambitious suitor. The couple married in 1908.

His business had been profitable enough to allow him to build a home at 5204 Harlem Ave. in Cleveland, where he later brought his mother to live, after his father died.

With Mary at his side, Morgan expanded his enterprises. The couple began manufacturing clothing, and developed a line of children’s garments.

Granddaughter Sandra Morgan remembers fondly the beautiful velvet coats with matching muffs that she wore as a little girl, all handmade by Mary. “My party coats, my summer clothes – my grandmother made everything.”

Garrett and Mary’s marriage lasted more than 50 years, until their deaths in the 1960s. Mary came from a big family, but she had little contact with her relatives after she married a black man. She was even excommunicated from her Catholic faith. Sandra Morgan, who still keeps Mary’s rosary and her Bible written in German, believes it hurt her grandmother deeply.

Garrett Morgan didn’t have much contact with his family either after leaving his native Kentucky. For him and his wife, their three children became their world, and they tried to keep their clan closely knit. “I can still remember going to my grandmother’s house, it was sacred. Every Sunday, you were at that house for dinner,” Sandra Morgan said.

And although she was just a young child in 1963 when her grandfather died, she remembers well the values he instilled. “When my grandfather came to Cleveland, he really did work with his hands and worked hard to pull himself up by his bootstraps.”

Her father, Garrett Jr., who pitched in to help his father sell his products, had a similar work ethic and passed that credo down to her: “There’s no slackers in the Morgan family” was a succinct motto they lived by.

At his home near East 55th Street and Superior Avenue, Garrett Morgan Sr. spent hours tinkering in his workshop, trying to come up with solutions to common problems. Around 1910, he had been working on a way to ease the scorching caused by a sewing machine’s rapid movement against wool, when he stumbled into a valuable discovery.

It happened by accident, when Morgan wiped his hands on a cloth after experimenting with a lye-based solution in his workshop.

Later, he noticed the woolen fibers had gone from crinkly to straight. Curious to see if he could replicate the result, Morgan experimented on a neighbor’s Airedale dog, and eureka: G.A. Morgan’s Hair Refining Cream was born.

It was the first product ever shown to chemically straighten kinky black hair – a forerunner to the popular hair relaxers of today — and Morgan shrewdly deduced its potential marketability. To go along with it, he developed a comprehensive line of hair care products, from his Hair-Lay-Fine Pomade that “makes unruly hair lay where you want it” to a special pressing comb for “heavy hair.” Morgan called his hair products “the only complete line of hair preparations in the world,” and soon he had a thriving business shipping the items to drugstores across the country.

He did whatever he thought it took to market his hair products. At one point, Morgan purchased a calliope and positioned the steam-powered organ inside a bus. He and son Garrett Jr. would blast the calliope loudly as they drove through Cleveland neighborhoods, attracting attention from people on the street whom they would then direct to drugstores that sold their creams and other items.

Around the same time, he was also working on “safety helmet” that he first developed in 1912. His intent, Morgan once wrote, was to invent an apparatus that could “provide a portable attachment which will enable a fireman to enter a house filled with thick suffocating gasses and smoke and to breathe freely for some time therein, and thereby enable him to perform his duties of saving lives and valuables without danger to himself.”

Morgan had long been aware of the fire hazard posed by wooden shanty houses like the ones in some areas of Cleveland and also in his rural Kentucky hometown. A fire could race through these homes in an instant, giving occupants barely seconds to get out. Morgan sometimes joked that that these homes went up in flames so quickly that the first thing to burn would be the fire bucket. But he was serious about the need to devise a solution.

In 1914, he patented his version of the gas mask. His safety hood had two tubes that extended to the floor, where Morgan assumed that fresh air was most likely to be found in case of fire. His device included a backpack of unpressurized reserve air.

Always quick to seek ways to sell his products after obtaining patents, Morgan traveled the nation after 1914 to demonstrate his device to fire departments. Knowing fire departments in the South would have no interest in enriching a black inventor, Morgan hired a white actor to pose as the inventor while Morgan dressed up as an Indian chief in New Orleans during a demo at the International Association of Fire Chiefs. During their schtick, the actor would announce that “Big Chief Mason” would don the mask and go inside a smoke-filled tent for 10 minutes. The audience was stunned when Morgan emerged unharmed after 15 minutes in the suffocating tent, and orders began to flow.

He had disguised his identity previously in 1911, when his mask won an award at the New York Safety Exposition. Again, he sent a white actor to accept the honor. “It was a little bittersweet that he couldn’t accept his own award,” said his granddaughter. “He couldn’t claim credit for his own work.”

Yet Morgan’s strategy paid off, literally. Mine owners and fire departments from across the United States and Europe began purchasing the hoods, and the U.S. Army used a slightly redesigned version of the Morgan mask during World War I.

The mask would endure a huge test in Morgan’s adopted hometown of Cleveland, when a group of miners was injured in a shaft under Lake Erie on July 25, 1916. An explosion had torn through an underwater tunnel, trapping more than a dozen men in an area filled with smoke and gas.

Morgan’s phone rang at 3 a.m. in the morning, summoning him to the scene. Still in his night clothes, he rushed to the lake with his safety hoods, bringing along his brother Frank and a neighbor.

Although rescue accounts differ, it is believed that his rescue team brought six men back to the surface and saved their lives, proving the hood’s effectiveness.

But the inventor’s heroism resulted in more slights. The Carnegie Hero Commission declined to recognize the Morgan rescue as an act of bravery. Even Morgan’s request for the city of Cleveland to help him with his medical bills, after he encountered noxious smoke in the waterworks tunnels, was unsuccessful.

Morgan’s granddaughter said her family also believes that sales of the gas mask began to drop as news traveled the nation that the inventor was a black man. “As far as I know, they were selling very well until it was discovered that the patent holder was black, and then sales dried up. That was very upsetting for him.”

Morgan, who had moved to Cleveland in search of opportunities denied to black men in the South, was clearly disappointed, Sandra Morgan said. He wanted nothing more than to be known as a “black Edison,” he told his family.

What he craved wasn’t the fame enjoyed by Thomas Edison, known nationally as “the Wizard of Menlo Park.”

Morgan wanted to live without limits, to be fairly remunerated for his many innovations and create a business empire as Edison had done. It disturbed him that he wasn’t afforded that chance. Of course, few inventors reached the heights achieved by Edison – it wasn’t just race that kept Morgan from following in his footsteps.

But opening doors closed to blacks had been a priority for Morgan throughout his life. A fervent bootstrapper, he believed strongly in doing all he could to strengthen Cleveland’s black community. In 1920, Morgan started a newspaper, the Cleveland Call, the predecessor to Cleveland’s Call & Post. Even this decision was a stab at righting a wrong against blacks. At the time, blacks weren’t allowed to advertise in white papers, and also reporting about blacks was considered negative and stereotypical.

By that time, Morgan had become a wealthy business owner with dozens of employees.

Automobiles were just becoming popular with the masses, and Morgan is believed to be one of the first black men in Cleveland to own one. From then on, “He always loved sweet-looking rides,” his granddaughter recalled with a laugh.

At the time, cars and horse-drawn buggies were all competing with pedestrians for space on Cleveland’s crowded streets. Morgan realized a device to control the haphazard traffic was needed, and devoted himself to inventing a solution.

On Nov. 20, 1923, he received a patent for the invention for which he’s best known: the traffic signal.

Although many say Morgan invented the traffic light, that is not technically true. There were no lights on Morgan’s device.

Morgan’s manually operated signal was mounted on a T-shaped pole. It gave people approaching an intersection three choices: stop, go or stop in all directions (which halted cars and buggies so that pedestrians could move safely).

General Electric, realizing the necessity for Morgan’s invention, purchased the patent from him for $40,000.

In 1923, he used some proceeds from sale to purchase a large piece of property near Wakeman, Ohio. There he created Ohio’s first black country club – a place where middle-class blacks could enjoy recreation like horseback riding, fishing and horseshoes. “The all-black facility, however, was not wanted in the area by local whites,” reported Renaissance magazine, which said that Klan members rode onto the property one night and burned a cross.

“Morgan and his brothers ran the m off with guns and warnings of their own. The KKK never returned, and the club enjoyed uninterrupted success until Morgan lost the bulk of his money in the 1929 stock market crash. With a freeze on his savings account, Morgan wisely sold 200 acres of the Wakeman land to pay the taxes on the remaining 200.”

Morgan died in 1963. The city of Cleveland never did grant his request for pension benefits in light of injuries sustained in the 1916 rescue.

Sandra Morgan said her family still has a letter that Morgan sent to Cleveland mayor Harry Davis expressing anger that he wasn’t compensated after the waterworks disaster. “I’m not an educated man, but I have a Ph.D from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment,” it began.

Did he die a bitter man? Sandra Morgan thinks not. Her grandfather had expressed disappointment many times over, but just as he tirelessly tested his inventions, Garrett Morgan took pride in surviving test after test of his mettle. The sale of the traffic signal had put him in a position where he didn’t have to work for anyone else any more, leaving him free to pursue the things that interested him most. And with that freedom came a sense of peace, she believes.

His headstone at Lakeview Cemetery reads simply: “By his deeds, he shall be remembered.”

And in 1991, 28 years after his death, one of his most heroic deeds — saving lives that seemed doomed in the underwater tunnel beneath Lake Erie — was remembered and recognized. The city of Cleveland finally honored Morgan by renaming its lakefront waterworks plant for him.

For more on Garrett Morgan, click here

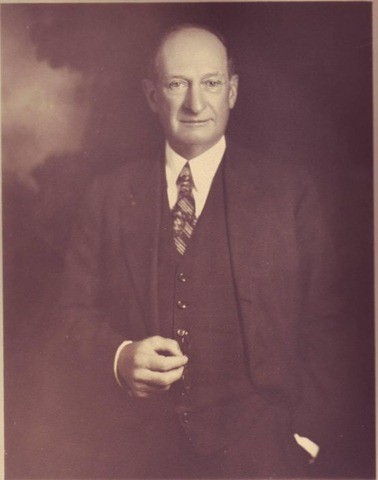

Maurice Maschke – The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland by Brent Larkin

Maurice Maschke – The Gentleman Boss of Cleveland

by Brent Larkin

More than 75 years after his death, memories of Maurice Maschke linger still in the minds of the precious few who remember a political boss whose power influenced almost every aspect of life in Cleveland.

“I was a young boy who grew up in his neighborhood,” Forest City Corp. executive Sam Miller recalled of the legendary Republican leader. “I remember well he was the person everyone went to if they wanted something done.”

Hall of Fame journalist Doris O’Donnell’s mother was a Democratic ward leader for party boss Ray T. Miller – Maschke’s longtime political rival.

“On Sundays, we had these large family dinners at our home in Old Brooklyn and invariably there would be talk about city politics, about Miller and Maschke,” said O’Donnell. “They were both very competitive – and very smart.”

Longtime Ohio Republican Party chair Bob Bennett cut his teeth in Cleveland politics during the 1960s. Back then, Bennett said the Republican old timers regularly spoke of Maschke in reverential terms.

“He set the standard for political bosses, for how to obtain power and use it effectively,” said Bennett. “He made things happen. And, most importantly, he knew how to choose the right candidates and win elections. After all, that’s what politics is all about.”

It is indeed.

And no one in Cleveland ever did it better than Maurice Maschke.

****************************

Born in Cleveland in 1868, Maschke grew up in the predominately Jewish neighborhood of lower Woodland Ave., a few miles southeast of downtown.

The son of a relatively successful grocer, Maschke was a bright young boy – so bright he was schooled at the prestigious Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and Harvard University near Boston.

Graduating from Harvard in 1890, Maschke returned to Cleveland where he studied to be a lawyer. While reading law, he landed a job as a clerk in the county courthouse, a place teeming with aspiring politicians.

It was around this time that Maschke befriended Robert McKisson, a rising star in city politics. Maschke signed on as a precinct worker in the McKisson political organization. In 1894, McKisson was elected to City Council. A year later, he was elected mayor.

That election increased Maschke’s stature within the Republican Party. And it enabled him to secure an important job in the county recorders office.

Maschke, it seemed, was on his way.

But McKisson soon clashed with Marcus Hanna, the Cleveland industrialist who in 1900 would engineer William McKinnley’s election as president. Hanna was, at the time, the nation’s most powerful political insider and McKisson’s falling out with Hanna contributed to his defeat in the mayoral election of 1899.

That defeat could have slowed Maschke’s political ascent, but by then the young East Sider no longer needed the support of a powerful political patron. He had figured how to advance on his own.

Maschke formed an alliance with Albert “Starlight” Boyd, the city’s black political boss, that served them both well. He also befriended Theodore Burton, an ambitious young congressman with a big Republican following.

In 1907, Burton unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Mayor Tom L. Johnson. But in early 1909, the legislature appointed Burton to the U.S. Senate. Maschke became Burton’s political eyes and ears back home.

Many now considered Maschke the city’s most powerful Republican operative. Later that year, he would prove them right.

After eight years in office, Tom L. Johnson had won the reputation as perhaps the nation’s greatest big city mayor. To this day, the progressive Democrat is revered for building an affordable, citywide transit system, providing low-cost electricity to residents through construction of a municipal light plant, and the opening of dozens of new parks.

But as the 1909 election approached, Maschke boldly predicted he had a candidate who could beat Johnson. Most regarded the claim as political puffery – especially when they heard Maschke’s candidate was Herman Baehr, the bland and inarticulate county recorder.

Nevertheless, Maschke was adamant. “Baehr will win,” he insisted. “Johnson has been mayor for eight years. That’s too long.”

True to form, Baehr proved to be a horrible campaigner. Johnson was so unimpressed by his opponent that, three days before the election, he left town.

He should have stayed. On Election Day, Baehr won decisively. Maschke, who became county recorder when Baehr vacated the job, was now the town’s preeminent political figure.

Next, Maschke would take his act to the biggest political stage of all.

At the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, President William Howard Taft was challenged by former President Theodore Roosevelt. As the convention opened, it appeared Taft had squandered his incumbent’s advantage – losing 9 of the 12 statewide primaries to Roosevelt, including his home state of Ohio.

But 100 years ago party bosses had a greater say in the presidential nominating process than rank and file voters. And in Chicago that year, perhaps no party boss had more clout than the Republican from Cleveland. When the roll was called, Maschke played a key role in Taft’s nomination.

That November, Taft lost the general election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, but not before he appointed Maschke to the coveted post as Northeast Ohio’s customs collector. It was Boss Maschke’s last public job.

****************************

By 1920, Maschke had formally taken charge of the entity he had, in actuality, controlled for a decade – the county Republican Party. He had also established a law firm, that would eventually make him a wealthy man.

In 1924, Cleveland switched to a city manager form of government – with the job being filled by William Hopkins, Maschke’s close friend. Hopkins was charismatic and visionary. He championed construction of a huge stadium on the lakefront and purchased land from Brook Park to build an airport.

But Cleveland’s population was changing. A steady influx of European immigrants added to the Democratic Party’s growing numbers. And Democratic Party chair Ray T. Miller, who doubled as county prosecutor, was shrewdly taking advantage of that growth.

Compounding Maschke’s political problems were corruption charges – and some convictions – of Republican party operatives. Maschke himself was charged for his alleged role in a scandal involving county government. But the case against him was weak, and Maschke was acquitted.

Nevertheless, criticism of the chairman was growing – even from some Republicans. Near the end of the 1920s, Maschke’s power at home was waning.

But on the national stage, Maschke summoned up one more grand performance. In 1928, he was a leading supporter and valuable political strategist to Herbert Hoover’s successful presidential campaign.

Once again, Maschke had a friend in the White House. At home, however, problems continued.

But by the late 1920s, Maschke and Hopkins had a huge falling out. Some speculated Maschke resented Hopkins’ popularity. Another theory held Maschke thought Hopkins didn’t do enough to support Maschke’s friends, the Van Sweringen brothers, during construction of the Terminal Tower.

Whatever the cause of the rift, Maschke, as usual, prevailed. In 1930 members of City Council, saying Hopkins had become power-hungry, fired him. Not long after, during an appearance at the City Club, Maschke said he had merely “put Hopkins back on the street where I found him.”

*********************

It is fair to wonder how Maschke, a Jew in a city where Jews represented only a fraction of the population, was able to dominate city politics for more than a two-decades-long period. The answer requires some educated speculation, but the answer is probably a combination of some or all of these factors:

Maschke’s religion was probably unknown to many, as it was hardly a common Jewish surname. What’s more, at the time, Republican rank and file were viewed as more progressive and open- minded than their working class Democratic counterparts.

And since Maschke never sought high office, his religion and ethnicity was never really a factor with the electorate. Had he run for congress or mayor, voters might have paid more attention to his background and beliefs.

Then, as now, results are what matter most to candidates and party operatives.

Maschke, however, was hardly the first political boss who was intelligent and understood how to win elections. What differentiated him from the others was his civility, honesty, perhaps even a sense of decency.

On that night of Maschke’s death, Roelif Loveland, considered one of the two or three greatest Cleveland journalists of all time, wrote of Maschke:

“To think of him – and we who knew him are not likely to forget him in a hurry – to think of him is to think of a man who was kind and gracious; who loved this city and his family and his party and truth and personal decency. To be sure, he gave the city about what its citizens wanted. If they wanted the town cleaned up, it was cleaned up. If they wanted it less rigid, it was less rigid.”

For all of Maschke’s endearing traits, what differentiated him from so many in public life was the well-rounded nature of his life. In the very first paragraph of an editorial following his death, the Plain Dealer noted his enormous political accomplishments, but also noted Maschke was a cultivated gentleman with many friends, lover of the classics, expert at bridge, devotee of golf – a polished, suave and delightful personality.

Maschke was hardly Cleveland’s last successful political boss. Nor is he the most renowned. That title probably belongs to Marcus Hanna.

But, for a time, Maurice Maschke probably accumulated and wielded more political power than any local leader before or since.

When he died of pneumonia on Nov. 19, 1936, the Plain Dealer’s coverage included 10 front page photographs and an obituary that started on Page One and ran for five pages inside.

In his tribute, Roelif Loveland recalled that during tense moments on election nights Maschke would seem to sometimes growl at his assistants.

“They pretended to be frightened” wrote Loveland. “But they weren’t.” Why?

“Because they loved him.”

To read more about Maurice Maschke, click here

Brent Larkin joined The Plain Dealer in 1981 and in 1991 became the director of the newspaper’s opinion pages. In October 2002 Larkin was inducted into The Cleveland Press Club’s Hall of Fame. Larkin retired from The Plain Dealer in May of 2009, but still writes a weekly column for the newspaper’s Sunday Forum section.

City Manager Plan from the Cleveland Encyclopedia of History

City Manager Plan from the Cleveland Encyclopedia of History

The CITY MANAGER PLAN and PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION ELECTIONS for city council members were key features of the City Charter approved by Cleveland voters in 1921. The two-pronged plan was an effort to provide more efficient and more responsive government by utilizing the managerial skills of a trained executive to administer the city, while a more representative council would make policy for the manager to carry out. The first of five (1923-31) proportional representation elections was held in 1923, and the first of two city managers took office in January 1924. At the time Cleveland was the largest and most diverse city in the U.S. to adopt such a system.

The manager, selected by the council, was responsible for law enforcement and the conduct of all city business. He had the power to appoint and remove all administrators except those covered by Civil Service. Four large districts replaced the 33 small wards as electoral units, each district electing 5, 6, or 7 councilmembers at-large, depending on population, for a total of 25 members who served 2-year terms. The Single Transferable Vote ballot (PR/STV) was nonpartisan and gave voters the opportunity to rank their candidate choices and to have their ballots transferred during the count to maximize their effectiveness.

In Jan. 1924, the council elected CLAYTON C. TOWNES† as mayor, a largely ceremonial position, and appointed WILLIAM R. HOPKINS† as city manager. In Jan. 1926, JOHN D. MARSHALL† succeeded Townes as mayor and was reelected by the council in 1928 and 1930. Although the plan was designed to minimize patronage practices, Hopkins was actually selected by Republican Party leader MAURICE MASCHKE† and Democratic Party leader W. BURR GONGWER†, who secured Hopkins’ agreement to split city patronage, with 60% of city jobs going to the dominant Republicans and 40% to cooperative Democrats. Hopkins exercised leadership in policy matters as well as administration, often preempting both the mayor and city council in the governing process. Five Charter repeal efforts were initiated. The first, in 1925, was aimed only at the PR electoral system but failed to pass. HARRY L. DAVIS†, who hoped to take over Republican party leadership and return as mayor, led three subsequent unsuccessful efforts to repeal both PR elections and the city manager plan (1927, 1928, and 1929). In 1930 a split between Maschke and Hopkins caused the Republican majority on council to fire Hopkins and appoint DANIEL MORGAN† in his place. Although Morgan had a better relationship with the council, he alienated Democrats by repudiating the patronage ratio agreement and hiring only Republicans at City Hall. In 1931 a commission led by Democrat Saul Danaceau placed charter repeal on the ballot. Generally, Republicans and reformers now opposed repeal, while Democrats, approaching majority status in the traditionally Republican-dominated city, supported a return to a popularly elected mayor and ward-based plurality elections for council. In Nov. 1931, a majority of voters approved the change.

While substantial public improvements were achieved during the City Manager/PR years, at the same time that taxes were reduced, voters did not attribute this progress to the form of city government. Instead, the electorate reacted to the perception that the city manager had overstepped his bounds, that corruption on the council had not been eliminated, and that the PR/STV was too complex. Finally, the rigors of the Depression created dissatisfaction with government in general.

Bromage, Arthur. Manager Plan Abandonments (1959).

Campbell, Thomas F. Daniel E. Morgan, 1877-1949 (1966).

Hallett, George. Proportional Representation (1940).

William Hopkins from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

William Hopkins from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

HOPKINS, WILLIAM ROWLAND (26 July 1869-9 Feb. 1961), lawyer, industrial developer, and Cleveland’s first city manager, was born in Johnstown, Pa., to David J. and Mary Jeffreys Hopkins. The family came to Cleveland in 1874. At 13, Hopkins began working in the Cleveland Rolling Mills, using his earnings to attend Western Reserve Academy, graduating in 1892. He earned his A.B. (1896) and LL.B. (1899) at Western Reserve University, being elected to CLEVELAND CITY COUNCIL as a Republican (1897-99) while in law school. Hopkins laid out new industrial plant developments, and in 1905 promoted construction of the Cleveland Short Line Railroad, linking Cleveland’s major industrial sections. He gave up his law practice in 1906 to devote himself to business.

Hopkins became chairman of the Republican county committee and a member of the election board and, with the approval of both political parties, became Cleveland’s first city manager in 1924. Removed from partisan politics, he developed parks, improved welfare institutions, began PUBLIC AUDITORIUM, and developed Cleveland Municipal Airport. Although as city manager he was administrative head, he also took the lead in determining policy. City council felt he acquired too much control and removed him from office in Jan. 1930. In 1931 he became a member of council, unsuccessfully fighting for retention of the CITY MANAGER PLAN. In 1933 he returned to private life. The airport was named in his honor in 1951 (see CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT). Hopkins married Ellen Louise Cozad in 1903; they had no children and divorced in 1926. He died in Cleveland and was buried in LAKE VIEW CEMETERY.

Cleveland Hopkins Airport from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Cleveland Hopkins Airport from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT is located 8 miles southwest of PUBLIC SQUARE at Brookpark Rd. and Riverside Dr. The airport, originally known as Cleveland Municipal, was renamed Cleveland-Hopkins Intl. Airport on 26 July 1951, to commemorate the 82nd birthday of WILLIAM R. HOPKINS†, who founded it. A municipal airport for the city was envisioned shortly after World War I, but the airfield did not became a reality until the federal government was satisfied that the city could provide an adequate facility for U.S. Air Mail planes stopping in Cleveland on their coast-to-coast flights. In 1925 City Manager William R. Hopkins obtained the city council’s agreement to issue bonds to build the airport on 1,040 acres of land at the Brookpark and Riverside intersection. Clearing and grading took place at record speed so that the U.S. Air Mail could inaugurate night flights on 1 July 1925. Its first terminal building, constructed in 1927, featured the world’s first airport control tower. Although the local news media criticized the airfield’s distant location, passengers were willing to make the long trek, as well as the general public, who curiously viewed activity at the field. The NATIONAL AIR RACES were first held in Cleveland in 1929 as part of the ceremonies dedicating Cleveland’s Municipal Airport.

Through the years, the city has expanded and modernized the facilities at Hopkins to meet increasing passenger demands. A new terminal building was built in 1956, and since then additional concourses and gates have been added–the South Concourse, opened in April 1968, and the North Concourse, opened in Aug. 1978. The baggage-handling and parking facilities also were enlarged and moving sidewalks and escalators were installed. On 15 Nov. 1968, direct rapid transit service to the airport began. The problems of jet noise and the need for more and longer runways have brought the city into conflict with the airport’s neighbors as it expanded into population centers adjacent to it. In the wake of airline deregulation in the 1970s, airlines established selected hubs from which to conduct their operations. As a result, United Airlines, once dominant at Hopkins, reduced its 110 daily flights from Cleveland in 1979 to just 13 in 1988. Hopkins enjoyed an increase in passenger traffic in the 1980s and early 1990s, attributed to an improved local economy and the ability of the airport to meet carrier needs quickly. In the interim, both Continental and USAir have increased their airport operations, with Continental using the airport as one of its national hubs. In 1995, based on hopes that Cleveland Hopkins Intl. Airport might become an international hub for the nation’s major airlines, expansion plans were well underway for lengthening the airport’s runways to accommodate the potential increase in air traffic.

A Strong Will Gave Birth to Cleveland Orchestra

Plain Dealer article written by Bob Rich and published on April 28, 1991

A STRONG WILL GAVE BIRTH TO CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA

Everything was up to date in Cleveland when the Cleveland Orchestra gave its first performance at Grays Armory on Dec. 11, 1918, under the baton of Nikolai Sokoloff – exactly one month after the armistice ending World War I.

According to the local papers, you could buy a Cadillac that could make it to the West Coast in 11 days. No price was mentioned – after all, Cadillac buyers shouldn’t ask. Men’s madras shirts at the May Co. were $1.85, flannel shirts $5. The Winton Hotel’s Rainbow Room and the Statler Hotel were advertising for New Year’s Eve parties. Shubert’s Colonial Theater was staging David Belasco’s “The Wanderer,” with a company of 125, a ballet of 50, and a flock of sheep!

But if you could afford the 25-cent admission price, the young, Russian-born conductor gave you a little shot of everything, opening with Victor Herbert, going on to Bizet, Tchaikovsky and Liadov, and closing with Liszt.

The gods and the critics were smiling on the orchestra that night. James Rogers, The Plain Dealer critic, found it “of excellent quality,” and Sokoloff “a leader of capacity and resources. He hitches his chariot to a star.” Wilson Smith of the Cleveland Press said delightedly, “Cleveland has at last a symphony orchestra.”

It hadn’t been an easy start-up. Only the determination of a very strong-willed lady, Adella Prentiss Hughes, would be able to take a grimy, brawling industrial town and turn it into a city that would someday be renowned as a music center.

Her timing was good – the conservative Euclid Ave. industrial elite were ready to pour their money back into the community. Cleveland had overtaken Cincinnati to become the largest city in Ohio, but it wasn’t in the same class, culturally speaking. The Queen City had been manufacturing pianos as far back as 1820, had established a Conservatory of Music in 1867 and founded its symphony in 1895.

By contrast, the most important building in Cleveland was the Standard Oil Co.’s Refinery No. 1.

It took Hughes many years of fund-raising, of booking subscription concerts with the help of her philanthropist friends, of hiring a talented young conductor and local musicians. And then, when all was finally ready by September of 1918, everything fell apart when a killer flu struck.

“What war with all its terrors could not accomplish has yet been brought to pass,” wrote The Plain Dealer. “Not Germans, but microbes have put the music-makers to flight.” Schools and colleges shut their doors; public gatherings were forbidden. But the plague lifted, and so did Cleveland’s spirits that December night in 1918.

Then the promotion started; Hughes and Sokoloff wanted to reach the whole family, children and businessmen. The string quartet went to public concerts and private musicales; recordings were made on the Brunswick label and broadcast on WTAM Radio. They held music memory contests for schoolchildren, pioneered in public school concerts. The orchestra was proclaimed a force for Americanization, and a women’s committee was organized that went after the suburbs; the audiences grew.

Hard-sell ads were run: “If you have civic pride, patronize our Cleveland Orchestra.” Popular programs were described in a 1923 ad as “pre-eminently concerts for the businessman.” Another said, “Next Sunday at Masonic Hall you can hear 90 artists for the price of a ticket to a movie. Don’t you want to hear a Strauss waltz, familiar opera selections, a lovely soloist, and a gorgeous orchestral piece that describes a battle? … All this for 50 cents?”

By the time the orchestra’s brand-new Severance Hall opened its doors in February 1931, musical director Sokoloff was becoming an increasingly lonely figure up on his new podium. The maestro was caught between pleasing established conservative tastes and trying to showcase new American and European composers. And then he was a little old-fashioned with his high collars, his flamboyant, theatrical method of conducting.

One glimpse into his character: In 1930 he had contributed $100 to the cause of repealing Prohibition, whereupon Billy Sunday denounced him from the pulpit of the Euclid Ave. Baptist Church as a “dirty foreigner” for attempting to overthrow Prohibition. Sokoloff promptly doubled his contribution. But the old optimism was gone from this workingman’s city, where the Depression had thrown many thousands out of work.

The plaintive tune, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” said more about Cleveland’s musical tastes than anything the maestro could whip up on the stage. When his contract wasn’t renewed in 1932, the loyal Hughes stepped down as orchestra manager, but stayed with the Musical Arts Association, which runs the orchestra, until she died in 1950.

The man who took over the baton was Artur Rodzinski, who came to Cleveland at the peak of his career. He was 41, charming, sophisticated, and had more talent than he had the self-discipline to control. But for all the uproar the maestro created during his 10-year stay, he brought national artistic stature to the orchestra and city.

Adella Prentiss Hughes

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

HUGHES, ADELLA PRENTISS (29 Nov. 1869-23 Aug. 1950), best known as the founder of the CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA, was born in Cleveland to Loren and Ellen Rouse Prentiss, graduated from Miss Fisher’s School for Girls in 1886, and from Vassar College in 1890 with a degree in music. After a grand tour of Europe, returning to Cleveland in 1891, she became a professional accompanist. Though successful in this role, Prentiss became interested in the broader aspects of musical promotion in Cleveland, and in 1898 began bringing various performers and orchestras to the city. By 1901, she was one of Cleveland’s major impresarios, regularly engaging orchestras to perform at GRAYS ARMORY. During the next 17 years she supplied the city with a series of musical attractions, including orchestras, opera, ballet, and chamber music. Seeing the need for a permanent orchestra, Hughes created the MUSICAL ARTS ASSN.. in 1915 from a nucleus of business and professional men to furnish support for her projects. It was through her influence that NIKOLAI SOKOLOFF† came to Cleveland. In 1918, she, Sokoloff, and the Musical Arts Assoc. joined forces to create the Cleveland Orchestra. She served as its first manager, holding that position for 15 years. She also held administrative positions in the Musical Arts Assoc. for 30 years, retiring in 1945 only to continue her philanthropic work. Adella Prentiss married Felix Hughes in 1904. The couple divorced in 1923.

Maurice Maschke from Philip W. Porter

from Cleveland: Confused City on a Seesaw

by Philip W. Porter

retired executive editor of the Plain Dealer

1976

courtesy of Cleveland State University, Special Collections

Maschke was much maligned, and unfairly so, by the Plain Dealer and Press editorial writers, but he bore the criticism philosophically. Reporters, on the other hand, learned that he always told them the truth, or nothing at all. He was respected by two generations of political writers. (An interesting paradox was that Maschke, a brilliant bridge player, one of the best in the country, was for years the favorite partner of the late Carl T. Robertson, the number two man among the PD editorial writers. Robertson, a determinedly independent man, refused to take part in writing denunciations of Maschke). Maschke was astute, well respected by other lawyers, by businessmen and even by his Democratic opponents. Tom L. Johnson praised him as a worthy opponent. Witt, though he professed a strong dislike of all bosses after Johnson died, praised Maschke publicly as a man of integrity (in contrast to his frequent aspersions against Hopkins). Gongwer respected and liked him. He was a ripe target for cartoonists and editorial writers. The name Maschke had a harsh, grating sound. He was bald, except for a wisp of hair on the back of his skull. He was not handsome. His large nose increased the prejudice of bigoted anti-Semites. He had a thin, reedy voice and seldom spoke in public until his later years, which was probably wise, for he was a poor public speaker.

Maschke went to Harvard (though he grew up in a poor neighborhood) both to the basic college and law school, and soon afterward gravitated into politics. He realized that the Republicans would have a tough time as long as Tom Johnson was running for mayor, so he concentrated on helping friends get elected to state and county offices. Two he helped were Ed Barry, who was elected sheriff, and Theodore E. Burton, elected to Congress, both despite a Democratic trend. Maschke sensed that Johnson’s popularity was beginning to erode and he rightly surmised that a respectable, colorless candidate might beat Johnson next time around. So he got his friend and protege, County Recorder Herman Baehr, to run for mayor in 1909. Maschke’s intuition was right. Baehr was the man nobody knew. He wouldn’t debate the brilliant campaigner Johnson. The people didn’t vote for Baehr; they voted against Johnson. (It was the old story of the Greeks deposing Aristides the Just, a man who was too good to be believed.) Maschke was now in the saddle as boss, after only twelve years as a practicing politician. He was appointed county recorder, to succeed his friend Baehr.

In 1911, Maschke was appointed customs collector by President William Howard Taft. In 1915, he was replaced by Burr Gongwer and began to practice law with John H. Orgill.

When Harry L. Davis was elected mayor in 1915, Maschke got back quickly into the city hall picture. The hall remained Republican all through World War 1. It was obvious that 1920 would be a Republican year nationally, too. Maschke sensed it early, and saw a chance to get into the national picture by coming out for Senator Harding. (The always Republican News endorsed General Leonard Wood, but Maschke’s delegates stuck with Harding, and won.)

The 1920 election, however, produced a temporary estrangement between Maschke and Governor Davis. Davis got the idea that Maschke had let him down in Cuyahoga County, which he almost lost. Maschke retorted that Davis had lost strength because his pro-labor attitude during the war had alienated businessmen in the suburbs as well as his home area, Newburgh, where the steel mills are located.

Maschke’s law practice was now making big money and he was on his way to becoming a wealthy man. His fees came largely from corporations, particularly from utilities, which were always deeply interested in getting legislation passed or killed. This type of law practice was, and is, the standard way for political bosses, and lobbyists, to make politics pay. Political law practice and political insurance business are the most familiar means, and they depend almost entirely on friendship and influence. If everything else is equal, few legislators, state, city, or national, will refuse a request from a party chairman to vote his way on a routine bill. And often on important bills, too. The boss makes promises, and holds the public officials to theirs. It has been a way of political life for centuries and still is.

The personal bitterness between Maschke and Hopkins continued even after Hopkins was ousted as manager. In the fall of 1931, when Hopkins was running for city council (to which he was later elected), they traded insults before the City Club Forum. Hopkins charged that Maschke had profited from city contracts, that contractors had hired him, that city employees were paying him for promotions, and that he, Hopkins, knew nothing about the 67/33-percent deal for jobs. Maschke retorted that Hopkins was a liar and an ingrate, “false, mendacious, spurious, a phrase-maker with an inherent capacity for deception,” and “I put him back on the sidewalk where Gongwer and I had picked him up in 1923.” It was a sensation.

Maschke in 1934 wrote his memoirs for the Plain Dealer, a remarkable thing for a political boss. In the final chapter, he described what qualities brought success in politics:

“Truthfulness, candor, foresight, courage, patience and a deep understanding of human nature. There is as much scheming in business as in politics, but in business it is mostly kept quiet. Politics is everyone’s business and it comes out. Truthfulness is supposed to be a normal quality of man, but somehow, truthfulness in politics distinguishes you.”

He was totally realistic about fame and fortune in politics. “When you win you are a great leader,” he said. “Lose a couple and people are ready to consign you to the ashheap.”

Maschke was way ahead of his time in understanding the value of racial integration in politics. He was the pioneer in backing such outstanding Negro public servants as Harry E. Davis for the legislature, school board, and civil service commission; Perry B. Jackson for the legislature, council, and municipal court; Clayborne George for council and the civil service commission. As long as Maschke was in charge, the black population of Cleveland remained Republican and stable. Today it is 95 percent Democratic and restless.

Maurice was also wise in his selection of first-rate candidates for the legislature. Not since the Maschke era has Cleveland been represented by legislators of the caliber of Dan Morgan, Harold Burton, John A. Hadden, John B. Dempsey, Herman L. Vail, David S. Ingalls, Ernest J. Bohn, Dudley S. Blossom, Chester C. Bolton, Laurence H. Norton, Mrs. Maude Waitt, and Mrs. Nettie M. Clapp. Choosing rich men like Blossom, Bolton, Norton, and Ingalls did Maschke no harm at campaign times, and it did the Establishment of that day no harm in having them on hand to make laws, but they were all first-rate, intelligent, concerned men, who took the lead in public affairs. Today it is hard to get men of real stature to run for the legislature and even harder to get them elected. In the Democratic era of the thirties, the Cleveland legislators were largely a bunch of zeros, hardly known beyond their neighborhoods, with little influence in Columbus. Later, the law was changed to elect legislators by districts, and the caliber of the candidates has improved some. It still is nowhere as high as it was in the twenties.

Maschke died of pneumonia in October 1936. His widow, Mrs. Minnie Rice Maschke, died at age ninety-five in March 1972. A son, businessman Maurice (Buddy) Jr., and a daughter, Mrs. Helen Maschke Hanna, still live in Cleveland.