Article about Margaret Bourke-White from American Heritage Magazine

The link is here

WOMAN OF STEEL

Margaret Bourke-White made industrial photography a powerful art form in the 1920s and 1930s

by Vicki Goldberg

Some say that traditional religion died in the nineteenth century and was supplanted in the twentieth by worship of the machine. A curious reverence for machinery did spring up in the first decade of this century, principally in Europe; in the United States the new “religion” did not make a strong showing until about 1927, despite the fact that expanding technology and the shift to an urban economy had transformed America into the most highly industrialized nation in the world. In the spring of 1927 the catalog for a New York show called “Machine-Age Exposition” declared: “Is not the machine today the most exuberant symbol of the mystery of human creation? Is it not the new mythical deity which weaves the legends and histories of the contemporary human drama? The Machine in its practical and material function comes to have today in human concepts and thoughts the significance of an ideal and spiritual inspiration.”

The nation had been fascinated by machines even before it learned to worship them. Pictures of industry were popular in the first quarter of the century, but industrial photography had not yet become a fine art. During the first two decades, Americans bought thousands of stereoscope slides of factories crammed with the new means of production; the pictures were straightforward, explanatory, factual, and uninspired. Then, around 1920, a few American painters and photographers, especially such artists as Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, and Ralston Crawford, in a group known as the Precisionists, began to create an artistic vocabulary capable of speaking for the machine age. Demuth titled his painting of grain elevators My Egypt, an ironic comparison of American monuments to the pyramids. The photographer Paul Strand was so intrigued with the mechanics of his movie camera that he opened it up and took close-up still photographs of its precision-turned interior.In the fall of that year, Margaret Bourke-White, newly graduated from Cornell, took her camera to the teeming industrial parks of Cleveland and began to photograph the smokestacks, freight cars, squat factory buildings, and bleak, mineral vistas of the industrial era. She was not the first to photograph machines, but her approach made industry so convincingly beautiful, dramatic, and romantic that she created the icons for America’s most recent popular devotion.

Bourke-White’s vision of industry was altogether different. Her camera concentrated on stark contrasts of flame and darkness; on the complex spaces of factories crowded with equipment; on the dynamic, repetitive forms of mass production. To Bourke-White, industry was a dramatic stage for the play of mechanical process, vivid light, and strong pattern. The photographs she took for advertisements and for Fortune magazine had a kind of cinematic grandeur that convinced her public that a new beauty had been born with the rise of technology. And at a time when salaried managers were taking over from older corporate entrepreneurs like Carnegie and Frick, Bourke-White’s grand, artistic images provided a new and efficient means of establishing a prestigious corporate identity.Late in 1927, at almost the moment Margaret Bourke-White began her industrial work, Henry Ford commissioned Sheeler to photograph the Ford River Rouge plant, not for specific advertising purposes but as a record of American technological invention. Sheeler saw the River Rouge as a great web of pure, sharp, static forms, a vast display of mechanical potential forever stilled by his photographs.

Bourke-White herself was convinced she was creating the only art for her time.“Any important art coming out of the industrial age,” she said, “will draw inspiration from industry, because industry is alive and vital. The beauty of industry lies in its truth and simplicity; every line is essential and therefore beautiful.”The idea that industrial forms could be art suited a general belief that technology and business would raise the world to greater heights. Henry Ford himself gave the “religion of the machine” its credo: “Machinery,” he said, “is the new Messiah.” By the late twenties Americans were prepared to believe that engineers were a new breed of artist who had spawned a new aesthetic. Within months after Bourke-White took her first industrial photographs, in the Otis Steel plant in Cleveland, the Associated Press headlined the exalted status of her pictures: GIRL’S PHOTOGRAPHS OF STEEL MANUFACTURE HAILED AS NEW ART.

As it happened, she had in her hands the perfect instrument for recording the essential dignity of mechanical invention. In 1930 the New York Times art critic wrote: “Photography is the machine-age art par excellence. The moving picture and the snap-shot mark the tempo of our time. The mass production implicit in the photographic process is economically modern.”

The new art began to appear everywhere, in ads, in Sunday rotogravure sections, in museums. Cleveland’s biggest bank enclosed its quarterly dividend checks in folders adorned with Bourke-White’s photographs of the steel industry. But the camera’s most lasting liaison with industry occurred in the pages of Fortune, which commenced publication mere months after the stock market crashed. Fortune’s luxurious format, handsome photographs, and emphasis on industry reassured America each month that the power of technology could pull the nation through any crisis. During the Depression, big business needed precisely the kind of symbolic, awe-inspiring photographs Bourke-White could produce on demand, for although her pictures did not sell nuts and bolts, they persuasively portrayed industry as reliable, powerful, and forward-looking.

In Fortune’s first issue Bourke-White was the only photographer with a credit line. She remained the magazine’s star for several years, and her name became synon1 ymous in the public mind with industrial photography. She had been hired when the magazine was still in the planning stages; at that point a friend remarked that if the magazine failed, she’d be known as “Miss Fortune.”

If people were surprised to discover that grain-elevator pipes and gigantic rolls of wet paper had artistic value, they were even more startled to learn that the photographer was an attractive woman in her twenties who wore fashionable clothes and bobbed her hair. What’s more, the “girl photographer” went to immense lengths to define the beauties of technology, learning to walk across scaffolds eight hundred feet above the sidewalk, moving in so close to the molten metal in a steel factory that the varnish on her camera blistered. In her diary, she wrote about one photograph, “I am glad that it is good, because it was so exciting to go up and take it through the carbon monoxide gas on the top of the coke oven, with my guide posted at the foot of the steps to run up and catch me if I should keel over.”

In the early stages of Bourke-White’s career, as in the early stages of machine art in general, the machine was clearly the hero, while the worker played a subsidiary role or remained offstage. But by the mid-thirties, even though Americans remained fascinated with technology, the Depression had compelled the country to pay attention to the plight of human beings. Margaret Bourke-White trained her lens more and more often on the worker behind the machine, and soon she began to try her hand at photojournalism, a genre always marked by a strong narrative interest in human stories and human events. When the premiere issue of Life, America’s first great picture magazine, reached the newsstands in 1936, Bourke-White’s photographs summed up the country’s preoccupations. On the cover her picture of Fort Peck Dam vaunted the majestic beauty of advanced engineering; in the lead story her depiction of the Fort Peck construction workers dancing, drinking, and playing the fiddle carried the implied message that the tough, plucky workingman and -woman could win the economic war.

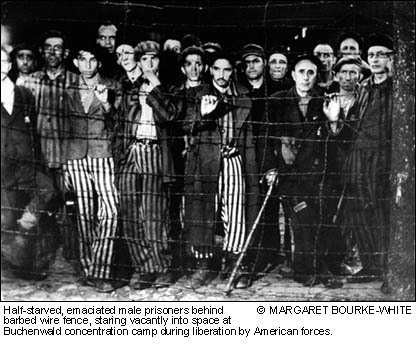

From time to time Bourke-White still took industrial photographs, most notably in a story on women steel-workers in World War H. Other photographers over the years would build on her theatrical, powerful style with its romantic light and modernist abstractions, a style that established the ground rules for industrial photography for years. But by the Second World War the country’s passionate devotion to technology had cooled down, the camera had been drafted to document a war, and the glory days of industrial photography had faded away with the exaggerated notion of machinery as a new Messiah. Bourke-White went on to photograph the German bombardment of Moscow, the liberation of Buchenwald, the partition of India, and the other major events of an era that still depended on technology but no longer chose to worship its machines.

Vicki Goldberg is the author of Margaret Bourke-White: A Biography (Harper & Row, 1986).

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.

Following her success at Fortune, Bourke-White became one of the first group of photographers hired by Life. Her photo graced the inaugural issue of the famous magazine. Her 1936 black and white cover photo of a massive dam validated her photography credentials in a field still dominated by men. The photo issued a statement that technology and American ability could overcome the economic depression of the 1930’s. During her years at Life, the magazine grew to national prominence thanks to the brilliant photos of Bourke-White and her colleagues.