From Clevelandjewishhistory.net

Category: Ethnic History of Cleveland

The Alsbacher Document

From Cleveland Jewish History.net

Vintage photo gallery of some of Cleveland’s early synagogues Cleveland.com 4.29.2016

Vintage photo gallery of some of Cleveland’s early synagogues Cleveland.com 4.29.2016

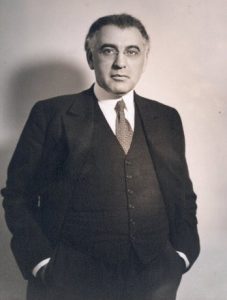

Meet John Anisfield, The Cleveland Philanthropist You Probably Haven’t Heard Of by Karen R. Long

Sharp-eyed Clevelanders can still spot John Anisfield’s name on the side of his old garment factory, which employed more than 700 workers a century ago. The clothing manufacturer at E. 22nd and Superior Avenue has been shuttered long decades, but the imprint of Anisfield, his fortune, and his progressive notions carry briskly into the 21st century.

John Anisfield was 16 and nearly penniless when he arrived in Cleveland in 1876, but he had an uncle, Dr. James Horowitz, who was able to place his Viennese nephew into the employ of the D. Black Cloak Company. Young John proved a quick study, rose to become a manager, quit and struck out into garment making on his own, just six years after he set foot in Cleveland.

The Civil War had remade the way Americans clothed themselves, as it remade so much of the country. The U.S. Army had taken millions of measurements of boys and men, begetting a system for sizing men’s clothing. This system and increasing mechanization fueled the ready-to-wear market from the 1860s through the 1880s, which coincided with young John’s arrival.

For approximately a half century after the 1890s, seven percent of Cleveland’s workforce toiled in the city’s garment factories, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

Many of the founders and owners were Jews of German or Austrian-Hungarian extraction. Four of the nine founders of the Jewish Federation – the Federation of Jewish Welfare Charities of 1903 – led the local garment-making firms, said Dr. Sean Martin, curator for Jewish History at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

During this fertile period, John Anisfield began inviting his only child, Edith, downtown to his office on Saturdays, where the two would consider the family’s philanthropy. She was just 12 in 1901 when this consultation began – a full 19 years before the country decided to give women the right to vote with the 19th Amendment.

The forward-looking father and precocious daughter (Edith could read French, German, and English) sent money to Mount Sinai Hospital, the first such Cleveland institution to accept patients regardless of creed or color. When John Anisfield died in 1929, his daughter took five years to decide how to honor him: a literary prize that became the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards.

“The most important legacy of the garment industry is its philanthropic legacy,” historian Martin told a packed audience at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage. “The wealth they generated – not just for themselves but for their employees – is still with us.”

Jews in Cleveland from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Jewish immigration to Cleveland, as elsewhere in America, can be divided into 2 distinct, overlapping periods. The German era (1837-1900) witnessed the settlement of Jewish GERMANS; the principal years of immigration ran to ca. 1875. In the East European era (1870-1924), Cleveland Jews increased from 3,500 in 1880 to approx. 85,000 in 1925, as Jewish RUSSIANS, POLES, Galicians, and ROMANIANS settled in the city. The social and cultural character of the two groups differed markedly, and through the mid-1930s they most often developed parallel and separate institutions and communities. The first Jews to make their home in Cleveland arrived in 1839 from Unsleben, Bavaria; among them was SIMSON THORMAN†, whose son Samuel was the first Jewish child born in the city. By 1840 there were 20 families and probably 20 single males residing in the city. The nascent community settled near the CENTRAL MARKET, generally east of the river, where it built its first institutions. In 1839 the Israelitic Society of Cleveland was established, which soon evolved into ANSHE CHESED (later called Fairmount Temple). The congregation erected a synagogue in 1846 on Eagle St. across from the market. Four years later, following a doctrinal dispute, a second congregation formed, TIFERETH ISRAEL. The occupational background of the immigrants was in the petty trades and artisan pools of Central Europe. The Jews who settled in Cleveland were primarily shopkeepers and peddlers, although a few were skilled craftsmen. Peddling was a common avenue for entrance into a more stable commercial pursuit. By the 1870s the community had grown and businesses expanded: young or newly arrived Jews no longer peddled goods, but received their business training as clerks or bookkeepers in the firms of relatives or landsmen. Jewish businessmen were involved in retail and wholesale dry goods, hides and furs, and grocery and clothing establishments, and, to a lesser degree, as commission merchants, shippers, and bankers. Still others, upon accumulating sufficient capital, became interested in manufacturing, especially clothing and textiles. By 1900 Cleveland’s largely Jewish-owned GARMENT INDUSTRY was among the most important in America.

As this community’s population increased and gained greater wealth, Jews moved eastward along Woodland and Central. By 1875 many Jews already lived east of Perry St. (E. 22nd), with several residing in the fashionable neighborhoods around Case Ave. (E. 40th). During the 1890s, Willson Ave (E. 55th) became the center of the German Jewish population and its array of new organizations and institutions. While small cultural societies such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Literary Society and the ZION MUSICAL SOCIETY (1861-73) were short-lived, fraternal organizations such as B’NAI B’RITH (1853) and clubs such as EXCELSIOR (1872) and the Hungarian Benevolent & Social Union endured. In 1864 B’nai B’rith District Lodges Nos. 2 and 6 chose Cleveland as the site for an orphan asylum to serve 16 states. Dedicated in 1868, the Jewish Orphan Asylum was located at E. 51st and Woodland, presaging the community’s move there. In 1882 the Order Kesher Shel Barzel established the Kesher Home for the Aged. Both agencies evolved into important service institutions, BELLEFAIRE and the MONTEFIORE HOME, respectively, and eventually came completely under Cleveland Jewish community auspices.

The most important institutions for 19th-century Cleveland Jewry remained congregations Anshe Chesed and Tifereth Israel for the Germans, and to a lesser extent, B’NAI JESHURUN for the Jewish HUNGARIANS. As the temples grew and members moved eastward, each erected new synagogues. In 1926 B’nai Jeshurun dedicated its Temple on the Heights, the first established Jewish congregation to move to CLEVELAND HEIGHTS Changes in appearance and ritual were also effected during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To minimize the differences between themselves and their non-Jewish neighbors, German Jews introduced family pews, organs and choirs, removed hats and prayer shawls, and hired rabbis who could preach in English on secular subjects.

In the 1870s Reform Judaism began adopting a liberal theological view that was embraced almost immediately by Tifereth Israel, and somewhat later by Anshe Chesed. The former adopted a Reform prayerbook in 1866, and in 1873 joined the newly established Reform umbrella organization, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Under the direction of Rabbi MOSES J. GRIES†, Tifereth Israel departed radically from traditional Judaism, and even from the mainstream of the Reform movement. During his tenure the Temple, as it was popularly called, adopted the Union Prayer Book, eliminated Hebrew from the Sunday school curriculum and from religious services, substituted an English translation of the Torah to be placed in the synagogue’s Ark, and changed Sabbath services from Saturday to Sunday. Less radical, Anshe Chesed embraced what became known as Classical Reform during the rabbinate of LOUIS WOLSEY† (1907-25).

When East European Jews fled the pogroms, restrictive social legislation, and economic dislocation of Eastern Europe and emigrated to America, they often discovered an affluent, entrenched German Jewish community that in most cases had more in common with its Protestant neighbors than with its newly arrived co-religionists. In Cleveland, the differences between the two groups embarrassed the German Jewish leadership and enraged the new immigrants. A handful of East European Jews lived in Cleveland as early as the late 1850s, and by 1880 there were 4 or 5 Orthodox congregations. They were joined by thousands who immigrated to Cleveland, especially during the peak years, 1904-14. The new immigrants settled in the areas that had been abandoned by the German and Hungarian Jews, and in the 1880s and 1890s resided side-by-side with other non-Jewish immigrants, particularly ITALIANS around Berg St., and Hungarians and CZECHS along lower Broadway. Like their German predecessors, the early East European Jews soon moved out of the Central Market area.

German Jews made several attempts to address immigrant charitable needs in the 1880s and 1890s, but with limited success. The most important such agency was the Hebrew Relief Society (est. 1875), which provided case-by-case aid. German Jewish aid combined self-interest, humane concern for fellow Jews, and paternalism. Seeing the foreignness of the East Europeans as a threat to their social standing, German Jews attempted to Americanize the new immigrants. To this end, the local NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN (NCJW), CLEVELAND SECTION created the Council Educational Alliance in 1899. The council offered a variety of classes designed to help the immigrants’ transition to an American way of life and served as the meeting place for the plethora of East European clubs and societies. Among the most important immigrant organizations were the social/benevolent societies, usually formed as landsmanshaften, groups of Jews from a common locale who banded together for social reasons and to aid and comfort members and assist newly arrived landsman in obtaining work. In addition to these functions, several landsmanshaften formed the nuclei for immigrant ethnic congregations, such as Anshe Grodno and TETIEVER AHAVATH ACHIM ANSHE SFARD.

Between 1895-1920 at least 25 Orthodox congregations were established in Cleveland. However, none approached the importance of the older ANSHE EMETH (PARK SYNAGOGUE). Before 1904, the Orthodox community had no rabbinical leader, although Rabbi BENJAMIN GITTELSOHN† was internally important for his scholarship and spiritual guidance. Rabbi SAMUEL MARGOLIES†, who came to the city in 1904, became the most influential Orthodox Jewish leader during the first quarter of the 20th century. His preeminence was based on his traditional Judaism, his appeal to Zionists, and his belief that Jews needed to Americanize as quickly as possible. The latter view led to the creation nationally of an American form of traditional Judaism–Conservative Judaism–that was embraced by Anshe Emeth in the 1920s and by B’nai Jeshurun somewhat earlier. Those two congregations by the mid-1920s ranked 3rd and 4th in membership behind the two Reform temples. None of the Orthodox congregations, which were primarily ethnic or landsmen shuls, could approximate the size of these 4 until after World War II.

East European Jewish immigrants, like the Germans, tended to enter mercantile occupations when possible. However, the opportunities available in the wide-open economy of the 19th century did not exist for the early 20th century immigrants. Over 15% of the East European Jews were engaged as peddlers or hucksters during the century’s first decades, while 25-33% operated small stores or worked as clerks in Jewish-owned establishments. The single most striking occupational difference between East European and German Jews was that 40-50% of the former worked in the skilled and semiskilled trades, especially as cigarmakers and in the building and needle trades. Fully 20% of the employed Jews in Woodland were found in the clothing industry, generally with large Jewish manufacturing firms such as JOSEPH & FEISS CO., PRINTZ-BIEDERMAN CO., and D. Black & Co. Despite the lack of opportunity to accumulate wealth on the same scale as the German Jews, the East Europeans did attain enough money to move to newer and more commodious areas. At the turn of the century, Lower Woodland was dilapidated, unsanitary, and unsafe. Most Jews had moved to the area around E. 35th St., and a decade later the center of the community had again pushed toward E. 55th St.

The Woodland district supported a vibrant Jewish culture from the late 1890s through 1915. Yiddish and Hebrew literary societies and debating societies abounded, the Yiddish theater flourished at the Perry and then the People’s theaters, and in 1908 Samuel Rocker founded the Yiddishe Tegliche Presse, followed by his Die YIDDISHE VELT (1911-58). However, the community lacked the size and insulation of others, such as New York’s Lower East Side; Woodland’s Yiddish life could not survive amid the pull and lure of Americanization or the migration outward. One Americanizing influence was public EDUCATION, which Jews supported almost without concession. Yet Jewish education was recognized as the only way to ensure that children did not stray from Judaism. During the first half of the 20th century, the afternoon Hebrew school was the preferred local form of Jewish education. In 1883 the East European immigrants founded a Talmud Torah (later the CLEVELAND HEBREW SCHOOLS) that offered traditional Jewish education in the cheder style (emphasizing religious study and originally using Yiddish only except for Hebrew and Aramaic texts). After 1904 Rabbi Margolies, Joshua Flock, and Aaron Garber emphasized Hebrew and Jewish nationalism. In the 1920s and 1930s, Talmud Torah director ABRAHAM H. FRIEDLAND† infused it with an even more pronounced Hebraist and Zionist philosophy. In 1924 the BUREAU OF JEWISH EDUCATION was created, with Friedland as director, to coordinate resources and provide direction.

The vast charitable and philanthropic need coupled with the competition for monies led the German Jewish leadership in 1903 to establish the Federation of Jewish Charities. This umbrella organization raised and disbursed funds to its beneficiary agencies, freeing them to concentrate on service. Initial recipients were the MONTEFIORE HOME, the Jewish Orphan Home, the Council of Jewish Women, Infant Orphan Mothers Society, Hebrew Relief Society, Mt. Sinai Hospital (later MT. SINAI MEDICAL CENTER), Council Educational Alliance, and Denver Consumptives Hospital. None of these were immigrant charities, reflecting federation policy of funding only “mature” organizations. This angered the East European Jewish leadership and led to the creation of 2 organizations that hoped to represent the entire community. TheUNION OF JEWISH ORGANIZATIONS (1906-09) experienced some success in ridding the public school system of some anti-Semitic practices. However, the lack of adequate financial support and opposition from the federation and the Reform congregations ensured its demise. In 1913 the shorter-lived Cleveland KEHILLAH was created by the former union leadership, but it suffered the same fate. Other immigrant institutions that paralleled those of the German Jews were longer-lived. The Orthodox Old Home, established in 1906 in reaction to the Montefiore Home’s refusal to maintain a kosher kitchen, has evolved into one of the largest and most advanced Jewish homes for the aged in the U.S., MENORAH PARK CENTER FOR THE AGING. And the Orthodox Orphan Home, created in 1920, ran a small but successful independent program until 1959, when it merged with the JEWISH CHILDREN’S BUREAU and later moved to Bellefaire.

The most divisive Jewish issue was Zionism. Small Zionist societies existed in Cleveland as early as 1897, but it was after the turn of the century, with increased immigration, that Zionism became the central force in the East European Jewish community. Zionist organizations proliferated in the early 1900s, from the Orthodox Mizrachi to the socialist Poale Zion and Farband. Rabbi Margolies, a well-known Zionist when he arrived in Cleveland, Rabbi Nachman Ebin, and ABRAHAM KOLINSKY† were among the principal leaders of Cleveland Zionism during the first 2 decades of the 20th century. Reform rabbis Gries and Wolsey opposed Zionism as separatist and as contradicting Reform ideology. However, in the 1920s Reform congregations came under the leadership of Rabbis ABBA HILLEL SILVER† (the Temple) and BARNETT ROBERT BRICKNER† (Anshe Chesed). Both rabbis were raised in the East European and Zionist milieu of the Lower East Side of New York, and both attained national and international stature in the Zionist movement.

Cleveland Jews began to desert Woodland and move eastward to GLENVILLE (28.5% by 1922) and to the Mt. Pleasant/Kinsman district (14% by 1922). By 1926 the Jewish population of Woodland decreased from 35,000 to 17,000, and 3 years later, to 1,400. The migrations had a slight class character. The Jews who moved to Glenville appear to have been the emerging European Jewish middle class, while the Jews of Mt. Pleasant/Kinsman have been characterized as proletarian, heavily concentrated in the trades. Many Jewish unions and Jewish socialist groups, most notably the WORKMEN’S CIRCLE, relocated in Kinsman.

Glenville was far more densely populated than Woodland. Its main thoroughfares were lined with small shops, kosher butchers, and delicatessens. Mt. Sinai Hospital was the first major social-service institution to relocate to Glenville (1916), followed by the Jewish Orthodox Old Home (1921). During the same year, Anshe Emeth moved to Glenville and dedicated the Jewish Center, the first such center west of the Alleghenies. By the early 1920s this Conservative congregation was the area’s most important social and recreational institution, the focal point of intellectual ferment and Zionist activity. Just as Woodland served as the birthplace of several German Jewish fortunes, Glenville provided a similar setting for some East European Jews, such as LEONARD RATNER† (FOREST CITY ENTERPRISES, INC.) and Julie Kravitz (the Pick-N-Pay food chain).

Kinsman was almost twice the geographic size of Glenville but held only about half as many Jews. Its John Adams High School was never more than 25% Jewish, compared to Glenville High School, which ran as high as 90%. The Jews who moved out of Woodland to Kinsman in the early 1920s settled between E. 118th and E. 123rd streets. By the early 1930s, the center of the population was between E. 135th and 147th, on the streets adjacent to Kinsman Ave. The Jews of Kinsman were relative newcomers to the city, as reflected in the development of the area’s congregations. Many Kinsman synagogues had existed for only a few years before moving from Woodland, and even more were established in Kinsman initially. Neveh Zedek on Union (est. 1920) was the largest area congregation, and the KINSMAN JEWISH CENTER (1930, synagogue dedicated in 1933) was smaller but of equal importance. Two other important institutions were the Council Educational Alliance and the Workmen’s Circle. The alliance, originally at E. 118th St., moved to E. 135th St. and Kinsman in 1928, across from the Carpenters Auditorium, which offered social activities. Workmen’s Hall, erected by Workmen’s Circle in 1927 at E. 147th and Kinsman, became the center of socialist and fraternal activity in the neighborhood as well as for the preservation of Yiddish culture, with lectures, entertainment, and a day school.

A small number of Jews lived on Cleveland’s west side before the turn of the century. By 1910 there were enough to form a congregation, B’nai Israel, known as the West Side Jewish Center in the 1940s. Most of the west-side Jews owned small shops during this period. In 1954 a group of Jews formed Beth Israel, a Reform congregation which merged with the West Side Jewish Center 3 years later to form BETH ISRAEL-WEST TEMPLE. Several members of Beth Israel formed the CLEVELAND COUNCIL ON SOVIET ANTI-SEMITISM (1963) to conduct activities on behalf of Soviet Jewry.

The Federation of Jewish Charities changed its name to the Jewish Welfare Federation in 1926. It implemented recommendations of a 1923 community study and admitted several immigrant institutions to constituent status in a move to patch up differences with East European Jews. A reorganization in 1930 created the Jewish Welfare Fund, and the Jewish Community Council was established in 1935. The former provided a more directed and systematic approach to community fundraising, and the latter addressed demands for democratization of community leadership. The council mediated internal community disputes, monitored anti-Semitism, and acted as the Jewish representative body to the general public. In 1951 the council merged with the Jewish Welfare Federation to form the JEWISH COMMUNITY FEDERATION, the community’s fundraising and policy arm.

Following World War II, the Jewish community began to push into the Heights and eastern suburbs. A small number of Jews settled in the Heights during the first decade of the 20th century. In 1905 wealthy German Jews established the OAKWOOD CLUB near Mayfield and Taylor roads. A few Orthodox Jews founded the Heights Orthodox Congregation (later the HEIGHTS JEWISH CENTER) in 1923, and B’nai Jeshurun dedicated the Temple on the Heights on Mayfield in 1925. Due to hostility from non-Jews, new residents often fought court battles to set aside restrictive covenants and to secure building rights for Jewish institutions, particularly in SHAKER HEIGHTS,BEACHWOOD, and PEPPER PIKE. The fear that exposure to American culture and the lack of intensive Jewish education would estrange 2nd- and 3rd-generation Jews from traditional Judaism was well-founded. Although congregations often boasted large memberships in the 1930s and 1940s, synagogues were all but empty on the Sabbath; few Jews took an active interest. Orthodox congregations, despite the dynamic and scholarly leadership of rabbis such as ISRAEL PORATH† and DAVID GENUTH†, were losing their hold on the children of members. However, following World War II Orthodoxy in Cleveland, as in America generally, experienced a resurgence that continued into the 1980s. In part, increased membership and activity resulted from societal alienation and a search for personal identity. In Cleveland, the Young Israel, Chabad Lubavitch, and the religiously tinged Betar Youth appealed to young Jews on dual religious and Zionist planes. Other factors–the proliferation of Orthodox day schools such as the HEBREW ACADEMY, the consolidation of congregations, and wealthy Orthodox philanthropists who freely supported religious causes–contributed to the increasing strength of the movement.

The postwar migration introduced an era of consolidation, especially among Orthodox congregations. The cost of relocating was more than small congregations could afford. The Jewish Community Federation effected mergers within the Orthodox community to increase memberships and treasuries, resulting in the creation of the TAYLOR ROAD SYNAGOGUE and WARRENSVILLE CENTER SYNAGOGUE, and the Heights Jewish Center. The area between Coventry Rd. and South Green Rd. in Cleveland Hts. became the heart of the Jewish community in the 1950s. Taylor Rd., the focal point by the late 1950s and early 1960s, witnessed the greatest concentration of Jewish institutions in the community’s history: the JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTER, PARK SYNAGOGUE, Montefiore Home, Council Gardens, Taylor Rd. Synagogue, Bureau of Jewish Education, Hebrew Academy, JEWISH FAMILY SERVICE ASSN., and a host of smaller synagogues and institutions. Yet Jews continued to move eastward, populating Beachwood, Pepper Pike, and even HUNTING VALLEY. Estimating conservatively that another wholesale move of institutions would cost the community $100 million, in 1969 the federation extracted promises from all major Jewish institutions to remain in the Heights. Only the Temple on the Heights, which had already purchased land near Brainard Rd., failed to agree. The federation established the HEIGHTS AREA PROJECT to encourage Jews to remain in the Heights and worked with community organizations, the police, and local government to ensure that the Heights remain socially, residentially, and politically stable. The federation also built new offices at E. 18th St. and Euclid Ave. in 1965 to symbolize its commitment to the welfare of the inner city.

The Reform movement also experienced a surge following World War II. In 1948 TEMPLE EMANU EL was created with the assistance of Anshe Chesed, the Temple, and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations to reach out to the unaffiliated. Under the direction of Rabbi Alan S. Green, the concept was immediately successful, and Emanu El in the 1980s was a large and growing congregation. Soon after its founding, a group of Jews who were dissatisfied with Reform’s return to Hebrew education and support of Zionism formed Suburban Temple, along ideological lines common to late 19th and early 20th century Reform. Reform, nationally in the 1970s and 1980s, established an aggressive outreach program to unaffiliated intermarried Jews. Many of its tenets, particularly recent decisions on issues such as patrilineal descent as a determinant of whether one is Jewish, have brought Reform into direct and bitter conflict with the Orthodox. The deep divisions remain evident in the Cleveland Jewish community, yet the Jewish Community Fed., per capita the most successful in the U.S., enjoyed unprecedented financial support from the Orthodox. Despite religious divisions, in the 1980s the Cleveland Jewish community was probably better organized and more united than at any previous time.

Scott Cline

Seattle Municipal Archives

Gartner, Lloyd P. History of the Jews of Cleveland (1978).

Pike, Kermit J., ed. A Guide to Jewish History Sources in the History Library of the Western Reserve Historical Society (1983).

Vincent, Sidney Z., and Judah Rubinstein. Merging Traditions: Jewish Life in Cleveland (1978).

The History of Jewish Cleveland

Courtesy of the Jewish Virtual Library and the Encyclopaedia Judaica

CLEVELAND, city situated in Northeast Ohio on Lake Erie. Its metropolitan area has the largest Jewish population in the state (81,500 in 1996). Jewish settlement began in the 1830s, when Daniel Maduro Peixotto (1800–43) joined the faculty of Willoughby Medical College in 1836 and Simson Thorman (1812–1881), a trader in hides, came from Unsleben, Bavaria, settling permanently in Cleveland in 1837. The opening of the Ohio and Erie canals and the development of stage routes provided countless economic opportunities for new immigrants, and Thorman must have written to his family in Unsleben; in 1839 a group of 19 departed on the sailing shipHoward and 15 made the trip to Cleveland, arriving in July of that year, joining two other men who had emigrated from Unsleben.

Community Life to 1865

The Unsleben group arrived in America prepared to continue Jewish observance. They carried with them an ethical testament, known as the Alsbacher Ethical Testament, written by their teacher in Unsleben, who implored them not to forsake their heritage. Simson Hopferman (later Hoffman) served as a ḥazzan and shoḥet.They had a Sefer Torah, and with enough men to form a minyan, established the Israelitic Society in 1839. In 1840 the group purchased land on Willett Street for a cemetery, and more Jewish settlers arrived. There were two married and five single women with the Howard group, and marriages and births quickly followed.

In 1841 internal divisions led to the formation of a second congregation, Anshe Chesed (today known as Anshe Chesed Fairmount Temple). The two groups reunited temporarily, but split again in 1850, when a group of some 20 dissidents left to establish Tifereth Israel (today known as The Temple – Tifereth Israel). Rabbi Isadore Kalisch (1816–1886), later coauthor with Isaac Mayer *Wise of the first American Reform prayer book, Minhag America, led the new congregation. Both congregations moved towards reform before the Civil War.

In addition to the congregations, there were six communal organizations that were established before the end of the Civil War, including a local chapter of B’nai B’rith (1853), the Hebrew Benevolent Society (1855), the Young Men’s Literary Society (1860), the Jewish Ladies Benevolent Society (1860), the Zion Singing Society (1861), and the Hungarian Aid Society (1863). These reflected the growth of the Jewish community to approximately 1,000 individuals, 78% from German states (primarily Bavaria), and 19% from the Austrian Empire (primarily Bohemia). Benjamin Franklin Peixotto (1834–1890) was a founder of some of these organizations; while living in Cleveland, he owned a clothing factory and wrote for the local newspaper, The Plain Dealer, before leaving the area.

Most of Cleveland’s Jews through the Civil War were laborers, peddlers, or small merchants, but even then they were gravitating toward the garment industry, which was to become the nation’s second largest concentration of such businesses. Several Jewish firms made uniforms for Civil War soldiers, including Sigmund Mann and Davis and Peixotto & Co. Some 38 men from Cleveland served in the Civil War, including Joseph A. Joel, later known for his comic description of a wartime Passoverseder published in the Jewish Messenger in 1862.

From 1865 to the 1890s

The Cleveland Jewish population grew from approximately 1,000 at the close of the Civil War to 3,500 in 1880. During this period the pioneering families and newer settlers established congregations and cultural institutions, built businesses, and were active in public affairs and politics. B’nai Jeshurun and Anshe Emeth (both still in existence in 2004 with the latter known today as Park Synagogue) were founded, respectively, by Hungarian and Polish immigrants in 1866 and 1869, while the earlier congregations, Anshe Chesed and Tifereth Israel, continued to grow. The Jewish Orphan Asylum (today known as Bellefaire) was established by B’nai B’rith in 1868 to care for the region’s Civil War orphans. The Hebrew Immigration Aid Society (1875) and Montefiore Home to serve the aged (1881) were formed to complete services to a growing community. The Jewish elite enjoyed the Excelsior Club (1872). The Anglo-Jewish press began with the Hebrew Observer in 1889; four years later the Jewish Review appeared, and the two merged as The Jewish Review and Observer in 1899. The Jewish Independent was founded in 1906.

Members of the community were successful in business and public affairs. Kaufman Hays (1835–1916) began as a peddler, and in 1894 took over the Cleveland Worsted Mills. Other major clothing manufacturers were Joseph and Feiss, Richman Brothers, Printz-Biederman, and Kaynee. The major department stores, Halles, The May Company, and Sterling Lindner, were owned or managed by Jews.

Jewish participation in general community life took many directions. By 1892 a number of Jewish merchants were members of the Cleveland Board of Trade, whose president that year was Frederick Mulhauser, a mill owner. Rabbi Moses J. Gries (1868–1918) was a trustee member of the Society of Organized Charities, founded in 1881. Baruch Mahler and Peter Zucker were presidents of the Board of Education (1884–85 and 1887–88), and Kaufman Hays was vice president of the City Council in 1888. Louis Black, of Hungarian origin, served as United States consul in Budapest under presidents Cleveland and Harrison. Joseph C. Bloch became the first Jewish judge in Cleveland.

The 1890s through World War I: The Impact of East European Immigration

The Jewish population of Cleveland increased greatly from the 1880s on, as East Europeans fled pogroms and economic hardships. In 1890 the Jewish population was over 5,000 and by 1900 it was 20,000; at the end of the immigration period the estimated Jewish population of Cleveland was between 90,000 and 100,000. Clustered in the Woodland Avenue/55th Street neighborhood, the East Europeans worked as peddlers, in small businesses, and as employees in the clothing industry dominated by the established firms of the preceding immigrant generation. The new settlers were more attached to Orthodox traditions, and decidedly poorer, putting a strain on the existing social institutions. The Cleveland Section of the National Council of Jewish Women (founded in 1894) created an ambitious social settlement house through the Council Educational Alliance in 1899. To prevent duplication of efforts in activities and fundraising, in 1903 the established leadership created the Federation of Jewish Charities. In spite of these efforts, there were tensions between the newcomers and the earlier settlers. The East Europeans created their own institutions, including the Yiddishe Velt, a newspaper established by Samuel Rocker in 1911, a Jewish Relief Society (1895), an Orthodox Home for the Aged (1906, today known as Menorah Park Center for Senior Living), and the Orthodox Orphan Home. An attempt to create an Orthodox hospital failed when the existing Mt. Sinai Hospital (founded in 1903) agreed to provide kosher food. Numerous landsmanshaften also helped new immigrants adjust to Cleveland life, and at least 25 small Orthodox congregations could be found in the neighborhood, often associated with their members’ place of origin in Europe. Yiddish theater flourished in the community; one of the theater owners, Harry “Czar” Bernstein (1856–1920), was also a colorful Republican ward boss.

Many of the East European immigrants brought with them a trade-union outlook. The years before World War I were the high point of Jewish labor activity, particularly in the garment industries, where a series of strikes, not all successful, took place. A notable example of Jewish trade unionism was the Jewish Carpenters’ Union Local No. 1750, chartered in 1903. In 1910 William Goldberg began his lifelong leadership of the union and became a prominent figure in Ohio labor circles. Years later the garment workers’ union and the carpenters’ local lost their Jewish character as Jewish occupations shifted to the professions, service industries, and business enterprises. Unique expressions of Jewish economic activity were the Cleveland Jewish Peddlers’ Association, formed in 1896, and the Hebrew Working Men’s Sick Benefit Association.

Jewish Life through World War II

With the East European influx into Cleveland also came enthusiasm for Zionism. While Reform rabbis Moses Gries and Louis Wolsey opposed the movement, Zionist groups of all political persuasions proliferated, especially after two new rabbis were installed at the Reform congregations, Abba Hillel *Silver (1893–1963) andBarnett R. *Brickner (1892–1958). Many national conferences were held in Cleveland, notably the 1921 meeting that led to a schism between the factions headed byLouis *Brandeis and Chaim *Weizmann. *Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization, was established in Cleveland in 1913, and a Cleveland nurse, Rachel (Rae) Landy (1884–1952), along with New Yorker Rose Kaplan began visiting nurse services in Palestine that year. Zionism also affected Jewish education. Abraham H. *Friedland (1892–1939), brought from New York to direct the Talmud Torah supplementary school system, infused Hebrew language and Zionist philosophy into its educational curriculum. He also headed the Bureau of Jewish Education (founded in 1924) until his death in 1939.

After World War I, the Jewish community migrated east of the Woodland neighborhood: Glenville, a city neighborhood northeast, became a center of middle-class life with Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform congregations, and boasted a much admired public school system which had illustrious graduates such as U.S. Senator Howard Metzenbaum (b. 1917) (D-Ohio) and Joe *Shuster (1914–92) and Jerome *Siegel (1914–1996), creators of the comic hero Superman. Mt. Pleasant-Kinsman, to the southeast, larger geographically but less densely Jewish, had only an Orthodox synagogue and was noted for its working-class and Yiddish-language atmosphere, with trade union headquarters and organizations such as the Workmen’s Circle. The more affluent began settling in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, and in 1926 B’nai Jeshurun, which had joined the Conservative movement, built an impressive structure in Cleveland Heights, where it was known for the next 55 years as Temple on the Heights.

The events of the 1930s – economic depression and increased local and international antisemitism – moved the Jewish community in various ways. First, the Federation of Jewish Charities underwent an effective reorganization, creating a Welfare Fund to coordinate fundraising and a Community Council to mediate local disputes and represent the Jewish community to the general public. Second, the nonsectarian League for Human Rights, led behind the scenes by Abba Hillel Silver, strongly reacted to events in Europe by boycotting German-made products, monitoring the German-American Bund and other such organizations’ local activities, and providing an organized response to German student exchange in Cleveland. Several Jewish Clevelanders, including David Miller (1908–1977) and Morris Stamm (1904–2000), served in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War.

By the eve of World War II, Cleveland Jewry had fewer internal disagreements as the more recent immigrants had acculturated and the leadership of major organizations was no longer exclusively in the hands of the earlier families’ descendants. Although there was never a Jewish mayor of Cleveland, Jews were active in local politics and in the judiciary. Alfred A. *Benesch (1879–1973) served for 37 years on the Cleveland Board of Education, Maurice Maschke (1868–1936) was a Republican leader between 1900 and 1940, and judges Samuel H. *Silbert (1883–1976) and Mary Belle Grossman (1879–1977) had long periods of service on the bench.

World War II and the Establishment of the State of Israel

Of the 8,500 Cleveland men and women who served in the armed forces during World War II, over 200 lost their lives. In 1943 Rabbi Barnett Brickner was selected by the National Jewish Welfare Board to serve as executive chairman of the Committee on Army and Navy Religious Activities and traveled throughout the war theaters. The Telshe Yeshiva was relocated in Cleveland, its rabbis escaping Europe prior to its destruction. Several thousand Holocaust survivors settled in the metropolitan area after the war was over.

In 1945 David *Ben-Gurion met with 17 Americans at the Sonneborn Institute to discuss strategies in anticipation of establishing the State of Israel. Among them was former Cleveland law director Ezra Z. *Shapiro (1903–1971), who would later immigrate to Israel to head *Keren Hayesod. Continuing his activist role in rallying the community to the Zionist cause, Abba Hillel Silver dramatically addressed the United Nations in 1947 calling for a Jewish state. Over the years, after the establishment of the state, the Israeli landscape would become dotted with schools, synagogues, community centers, parks, and businesses bearing the names of Cleveland-area philanthropists and Zionists, including Max Apple, the Mandel, Ratner, and Stone families, and the Cleveland sections of ZOA, Hadassah, Na’amat USA, Amit Women, and the Histadrut.

Post–World War II through the 1970s

The trickle of families into the Eastern suburbs accelerated after World War II, and the bulk of the population relocated to Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, South Euclid, University Heights, and Beachwood despite some restrictive covenants that were overturned. Institutions quickly followed, leading to the merger of no fewer than 15 smaller Orthodox congregations into Taylor Road Synagogue, Warrensville Center Synagogue, Green Road Synagogue, and Heights Jewish Center. The massive Cleveland Jewish Center, originally Anshe Emeth, relocated from Glenville into an architecturally notable building in Cleveland Heights designed by Eric Mendelsohn, and became known as Park Synagogue. This congregation had joined the Conservative movement earlier in the century after a fierce legal battle. The Reform movement experienced growth in the suburbs as well. Two new congregations, Emanu El and Suburban Temple, were founded. Arthur J. *Lelyveld (1913–1996) led Anshe Chesed Fairmount Temple from 1958 to 1986. Active in the civil rights movement, Lelyveld was severely beaten in Mississippi in 1964, and also officiated at the funeral of slain civil rights worker Andrew Goodman. At the Temple-Tifereth Israel, Daniel Jeremy Silver (1928–1989) became senior rabbi upon the death of his father, Abba Hillel Silver; he oversaw that congregation’s building of a satellite structure in the suburbs, published several scholarly works, and was instrumental in establishing the National Foundation for Jewish Culture.

Although a 1962 book called Cleveland “a city without Jews,” this was not strictly accurate, as Beth Israel-The West Temple served the Jews living on Cleveland’s West Side. This small congregation made several important contributions to Cleveland’s Jewish history. Scientists were important in its founding, among them Abe Silverstein (1920–2002), who worked at the nearby NASA Lewis Research Station and contributed to the Mercury and Apollo programs of the U.S. space effort. One of the congregation’s students, Sally *Priesand, went on to become the nation’s first female rabbi, and in 1963 three of its members founded the Cleveland Council on Soviet Antisemitism, the first known advocacy group in the Soviet Jewry movement which would eventually lead to some 6,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union settling in Northeast Ohio.

This was an extremely productive time for the Jewish Community Federation, which in 1951 merged its two divisions, the Jewish Welfare Federation and the Jewish Community Council. Under the leadership of Sidney Z. Vincent (1912–1982) and Henry L. Zucker (1910–1998), the Federation was the first in the nation to directly fund day school education (to the Orthodox Hebrew Academy), pioneered leadership training courses, and developed a comprehensive approach to building endowment funds. Cleveland was subsequently known as the most successful city in the United States in per capita fundraising as well as a training ground for future federation directors. In later years, Boston, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Seattle, and New York, among others, would be headed by individuals who started their careers in Cleveland.

The workforce moved from the labor unions into the professions, service industries, light manufacturing, and banking. Fewer spoke Yiddish, and the longtime Yiddish newspaper ceased publication in 1952. In 1964 the two English-language newspapers became the Cleveland Jewish News, which continues as an independent publication.

1975 to 2006

In the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st, the Cleveland Jewish community has been concerned with geography and identity. The numbers appear to have remained constant; although a 1987 population survey showed a decline to 65,000, the 1996 survey estimated the population to be 81,500, casting some doubts on the previous survey’s methodology. The inner ring eastern suburbs house nearly half of this population, yet movement to more affluent areas farther east continues, including institutions. A concerted effort by the Jewish Community Federation to slow population movement from Cleveland Heights has succeeded to some extent in keeping several centers of Jewish life viable. In Cleveland Heights, the Taylor Road area is home to kosher stores, the Jewish Education Center of Cleveland (a reconfigured Bureau of Jewish Education, founded earlier in the century), several Orthodox synagogues, including a Taylor Road Synagogue with a much smaller membership, and two large Orthodox day schools. Hebrew Academy, Cleveland’s first day school, continues to thrive in its Taylor Road location, while the ultra-Orthodox-built Mosdos Ohr Hatorah’s girl’s division is close by. Park Synagogue (Conservative) has its main sanctuary several blocks away, and a new egalitarian traditional congregation purchased Sinai Synagogue, whose members now meet farther east in University Heights. Chevrei Tikva, a congregation reaching out to gays and lesbians (founded in 1983), also meets in Cleveland Heights. In University Heights, Fuchs Mizrachi School (founded in 1983) has grown rapidly to over 300 students, from preschool through high school in a Zionist, Orthodox setting.

Another center of Orthodox life flourishes in the Green Road area, the border between Beachwood and University Heights. Green Road Synagogue moved here in 1972, later joined by Chabad of Beachwood and Young Israel in reconverted houses. In the late 1990s, Chabad, Young Israel, and the Hebrew Academy proposed building plans for an Orthodox campus in this location, which were accepted, rejected, and then accepted with modifications during a period of contentious discussions noted nationally as an example of dissension within the Jewish community. The Jewish Federation created a task force, B’Yachad/Together, to try to heal some of these rifts. The Beatrice Stone Yavne School for Girls has since been built, as has the new Young Israel building, with Chabad under construction at this writing. The Green Road area also has kosher food stores, restaurants, and gift shops.

The Laura and Alvin Siegal College of Jewish Studies, formerly housed on Taylor Road, moved to a new building in Beachwood, which it shares with the Agnon School, a community day school. This campus also houses the Mandel Jewish Community Center in its only remaining building now that the Cleveland Heights JCChas been sold; the eastern satellite of Temple-Tifereth Israel; and the new (2005) Milton and Tamar Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage, a collaborative effort of the Temple-Tifereth Israel, the Jewish Community Federation, and the Maltz family, with many artifacts and documents from the Cleveland Jewish Archives collections of the Western Reserve Historical Society. Slightly to the east in Pepper Pike are B’nai Jeshurun and the Gross Schechter School, both associated with the Conservative movement.

Despite continued strength in the inner suburbs, buildings housing Jewish institutions continue to be constructed in suburbs farther east, with a new branch of the Cleveland Hebrew Schools under construction in Solon, Montefiore Home’s assisted living facility in Bainbridge, along with several small congregations.

Mt. Sinai Hospital, after a near century of providing outstanding health care, research breakthroughs, and opportunities for Jewish physicians, was sold to a for-profit health care system that eventually dissolved the hospital. Jewish physicians and scientists have increasingly made their mark at the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and Case Western Reserve University, where earlier Albert *Michelson (1852–1931) won a Nobel Prize in 1907, and Harry Goldblatt (1891–1977) made notable contributions in the field of renal hypertension. Philanthropic dollars have constructed major buildings at each of these facilities, including the Lerner Research Building and the Sam and Maria Miller Emergency Room at the Cleveland Clinic, the Mandel School of Advanced Social Services, the Peter B. Lewis Building of the Weatherhead Business School and the Wolstein Research Building at Case Western Reserve University, and the Horvitz Tower at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital. In the business world, the Stone and Weiss families continue to lead the American Greetings Corporation, the Ratner family heads Forest City Enterprises, a major construction firm, and Peter Lewis’ Progressive Insurance Company employs over 14,000 workers.

In politics, Beryl Rothschild, Harvey Friedman, and Merle Gordon served as mayors of University Heights and Beachwood; in addition to Howard Metzenbaum in the U.S. Senate, Eric Fingerhut has represented the district in Ohio state government. Milton A. Wolf served as ambassador to Austria during the Carter administration.

Contributions to the Arts and Popular Culture

Cleveland Jews have enriched the cultural life of the community in many areas. In literature, Martha Wolfenstein, Jo *Sinclair, Herbert *Gold, Jerome Lawrence, and more recently, Alix Kates Shulman, Susan Orlean, and Harvey Pekar worked in Northeast Ohio. David Dietz was a noted science writer, while David B. Guralnik (1920–2001) was the chief editor of Webster’s New World Dictionary for more than 40 years. Abraham H. Friedland, Libbie Braverman (1900–1990), and Bea Stadtler (1921–2000) wrote in the field of Jewish education. In the visual arts, Max Kalish (1891–1945), William *Zorach (1887–1966), and Louis Loeb were sculptors, Abel and Alex Warshawsky were painters, and Louis Rorimer (1872–1939) was influential in interior design. In music, Nikolai Sokoloff (1886–1965) was the first conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra; composer Ernest *Bloch (1880–1959) was the first director of the Cleveland School of Music and Arthur *Loesser(1894–1969) and Beryl *Rubinstein (1898–1952) led the piano departments at the school. Cleveland has also been called the birthplace of rock and roll music, beginning with the 1952 Moondog Coronation Ball, led by disk jockey Alan *Freed (1922–1965). Dorothy Fuldheim (1893–1989) was the first woman in America with her own television news program. Some Cleveland Jewish individuals and families have long been interested in professional sports. Max Rosenblum founded a professional basketball team in the 1920s. Members of the Gries family, Art *Modell, and Alfred Lerner all owned or shared in the ownership of the Cleveland Browns football team.

Garment Industry in Cleveland from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The Garment Industry in Northeast Ohio from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

GARMENT INDUSTRY. As early as 1860 the manufacture of ready-to-wear clothing became one of Cleveland’s leading industries. The garment industry probably reached its peak during the 1920s, when Cleveland ranked close to New York as one of the country’s leading centers for garment production. During the Depression and continuing after World War II, the garment industry in Cleveland declined. Scores of plants moved out of the area, were sold, or closed their doors. Local factors certainly played their part, but the rise of the ready-to-wear industry in Cleveland, as well as its decline, paralleled the growth and decline of the industry nationwide. Thus the story of the garment industry in Cleveland is a local or regional variant of a much broader phenomenon.

In the early 19th century clothing was still handmade, produced for the family by women in the household or custom-made for the more well-to-do by tailors and seamstresses. The first production of ready-to-wear garments was stimulated by the needs of sailors, slaves, and miners. Although still hand-produced, this early ready-to-wear industry laid the foundations for the vast expansion and mechanization of the industry. The ready-to-wear industry grew enormously from the 1860s to the 1880s for a variety of reasons. Increasing mechanization was one factor. In addition, systems for sizing men’s and boys’ clothing were highly developed, based on millions of measurements obtained by the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Eventually, accurate sizing for women’s clothing was also developed. The Depression of 1873 contributed to the growth and growing acceptance of men’s ready-to-wear, because men found in off-the-rack garments a satisfactory and less costly alternative to custom-made clothing. The production of ready-made men’s trousers or “pants,” separate from suits, stimulated during the depression of the 1870s, allowed men to supplement their outfit without having to purchase a complete suit. In general, however, the great expansion of the ready-to-wear industry coincided with and was partly the result of the tremendous urbanization and the great wave of immigrants that came to the U.S. in the last decades of the 19th century and early decades of the 20th. Industrial cities such as Cleveland also experienced rapid growth, and it was during this period that Cleveland’s ready-to-wear clothing industry blossomed.

The early entrepreneurs of the clothing industry in Cleveland were often JEWS & JUDAISM of German or Austro-Hungarian extraction. Their previous experience in retailing prepared them for the transition to manufacturing and wholesaling ready-to-wear clothing. One example was Kaufman Koch, a clothing retailer whose firm eventually evolved into the JOSEPH & FEISS CO., a leading manufacturer of men’s clothing. The company still exists in the early 1990s, although it is no longer locally owned. The entry-level manufacturer needed relatively little capital to launch a garment factory. H. Black & Co., which would become a major Cleveland manufacturer of women’s suits and cloaks, started out as a notions house. The Black family, Jews of Hungarian origin, decided to produce ready-to-wear clothing based on European patterns in their own home. Later, fabric was contracted out to home sewers and then returned to the factory for final assembly. This system of contracting was widely practiced at this stage of the garment industry’s development, but by the close of the 19th century home work had been generally superseded by factory production. Garment manufacturing started in the FLATS, but in the early 20th century, it was concentrated in what is now called the WAREHOUSE DISTRICT, an area bounded by W. 6th and W. 9th streets and Lakeside and Superior avenues. L. N. Gross Co., founded in 1900, was one such firm in the growing garment district, specializing in the production of women’s shirtwaists. Many women wore suits, and the separate shirtwaist provided a relatively inexpensive way to modify and vary their wardrobe. L. N. Gross also pioneered in the specialization and division of labor in the manufacturing process. Instead of having one person produce an entire garment, each garment worker specialized in one procedure, and then the entire garment was assembled.

As the garment industry spread to other areas of the city, the CLEVELAND WORSTED MILL CO. dominated the skyline on Broadway near E. 55th St. First organized in the 1870s and controlled after 1893 by KAUFMAN HAYS†, the Worsted Mills produced fabric for Cleveland manufacturers, as well as for garment manufacturers in other parts of the country. The company owned and operated a total of 11 mills in Ohio and on the East Coast. During the first 3 decades of the 20th century, the garment industry spread from downtown to the east side along Superior Ave. between E. 22nd and E. 26th streets. The RICHMAN BROTHERS CO. built a large plant on E. 55th. near St. Clair. Founded in Portsmouth, OH, the company moved to Cleveland in the late 1890s, specializing in the production of men’s suits and coats–an activity in which Cleveland was a close runner-up to New York. In order to reduce the risk of large cancellations by wholesalers, Richman distributed its product directly to the customer in its own retail outlets. The plants of other garment manufacturers dotted the east side well into the 1960s, including BOBBIE BROOKS, INC. on Perkins Ave. and the Dalton Co. at E 66th and Euclid. The PRINTZ-BIEDERMAN CO.was founded in 1893 by Moritz Printz, for many years the chief designer for H. Black & Co. Printz-Biederman specialized in the production of women’s suits and coats, a branch of the garment industry in which Cleveland ranked second to New York. In 1934 the company left the St. Clair area to build a modern factory on E. 61st between Euclid and Chester avenues. The large knitwear firm of Bamberger-Reinthal built a plant on Kinsman at E. 61st St.; Joseph & Feiss was located on the west side on W. 53rd St.; Federal Knitting had a plant on W. 28th and Detroit,; and the Phoenix Dye Works was still located on W. 150th St. in 1993.

For approximately 50 years after the 1890s, about 7% of Cleveland’s workforce toiled in the garment factories. The ethnic origins of those who worked in the industry were as varied as the immigrants who flowed to the U.S. in the early decades of the 20th century. Although Jewish workers played a prominent role, other immigrant groups such as CZECHS, POLES, GERMANS, and ITALIANS were also employed in large numbers, and many of the garment factories were located in the ethnic neighborhoods from which they drew their workforce. Small workshops also proliferated in the ethnic neighborhoods, and many garment workers labored in sweatshop conditions. Unlike in New York, however, where the majority of shops employed 5 or fewer workers, 80% of Cleveland’s approximately 10,000 apparel workers were employed in large and well-equipped factories by 1910. Although working conditions were somewhat better in Cleveland than in New York, Cleveland garment workers generally received low wages and worked long hours with few, if any, benefits. Like garment workers elsewhere, they sought to improve their wages and working conditions by organizing. In 1900 a number of small craft and trade unions joined together in New York City to form the INTERNATIONAL LADIES GARMENT WORKERS UNION, and in 1911 Cleveland garment workers staged a massive strike. On 6 June the employees of H. Black & Co. walked out, and up to 6,000 of Cleveland’s garment workers followed them. The ILGWU sent officials from New York to encourage the strikers, but in spite of considerable support for the workers in the community at large, the owners resisted. Attempts to negotiate a settlement failed, and by October those who could returned to work. The strike had been lost (see GARMENT WORKERS’ STRIKE OF 1911).

During World War I, the garment industry produced a variety of apparel for the armed forces, and in 1918 wartime inflation and prosperity prompted the ILGWU to organize another strike in Cleveland, involving approximately 5,000 workers. To avoid the disruption of local production of military uniforms, secretary of war and former Cleveland mayor NEWTON D. BAKER† intervened, prevailing on both sides to accept a board of referees, which gave the workers a substantial increase in wages. This event marked a watershed in relations between management and labor in Cleveland’s garment industry. The threat of unionization and the influence of “Taylorism” or “Scientific Management” persuaded the large Cleveland garment factories to provide increased amenities for their workers, which reached a peak in the 1920s. PAUL FEISS†, of Joseph & Feiss, was a convinced exponent of scientific management, and time and motion studies were implemented in order to make production more efficient and cost-effective. Working conditions also were improved in order to reduce employee turnover and to provide the best possible environment for maximum productivity. The local garment factories began to provide clean and well-run cafeterias, clinics, libraries, and nurseries for children. Employees of both sexes were urged to participate in sports, theatricals, and other activities, and the factory was also a place where immigrants learned English and a variety of homemaking skills. One consequence of paternalism was a brake on the growth of unionism.

The Depression and the New Deal had a major impact on the garment industry. Those manufacturers who survived the Depression were faced with a powerful new labor movement bent on organizing the unorganized garment industry. Bolstered by the provisions of the NRA and the National Labor Relations Act, both the ILGWU and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, which represented workers in the men’s garment factories, successfully waged organizing campaigns (see AMALGAMATED CLOTHING AND TEXTILE WORKERS UNION). Some owners acquiesced; others resisted or simply closed their doors. The process of decline in Cleveland’s garment industry began during the 1930s. During World War II, the industry was once again geared for war production. Factories produced uniforms, knit scarves, and parachutes. LION KNITTING MILLS was famous for its production of the knitted Navy watch cap. Following the war, a number of garment manufacturers were unable to adjust to new market conditions and to new price levels. But while some companies fell by the way, new and vigorous garment factories grew, especially in the 1950s. Among them was Bobbie Brooks, founded by MAURICE SALTZMAN†, and the Dalton Co., organized by Arthur Dery. In fact, the Cleveland garment industry was still so large and influential in the 1950s that Cleveland manufacturers were able to convince the Phoenix Dye Works of Chicago to relocate in Cleveland, where many of its customers were located. Throughout the years other businesses ancillary to garment manufacturing also flourished in Cleveland.

Since World War II, the once-vigorous Cleveland garment industry has dwindled considerably, especially since the 1960s and 1970s when the decline accelerated. In some instances, management has transferred manufacturing operations elsewhere while retaining offices in Cleveland. In some cases an entire operation moved from the Cleveland area, usually to the South. Many companies sold off all or part of their businesses or simply closed. The reasons for this shift are complex and varied, some deriving from local conditions and some from conditions that are national or even global in nature, affecting the industry as a whole throughout the U.S.

The garment industry is traditionally a low-paying industry, and rising labor costs aggravated the industry’s problems. Although most of the large Cleveland manufacturers were unionized, unionization itself did not necessarily mean that one company had an unfair advantage over another. The city’s garment unions, however, generally sought and received wage settlements above the national minimum. Labor costs were considerably less in the South, and Cleveland manufacturers as well as garment and textile workers throughout the U.S. faced growing competition from lower-paid workers in other parts of the world. For example, knitwear and other textile products produced in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Singapore could be sold in the U.S. at substantially less than the same products manufactured in this country. Another factor that may have discouraged some Cleveland manufacturers was the changing workforce. Until the 1950s and 1960s, many women workers had a limited number of employment opportunities, particularly the European immigrant women who dominated the workforce of the garment industry. During the postwar period, there was a new generation of women working who had many more employment opportunities at wages much higher than could be earned in the garment industry. However, while labor costs in Cleveland were relatively high in comparison with some regions, there were some industry authorities who contended that additional factors contributed to the industry’s decline. For example, some family-owned concerns were sold or simply dissolved when family shareholders could no longer agree on management decisions. In other cases, the heirs preferred some profession or occupation outside the garment industry.

The apparel industry was also subject to changes in technology and to the rapidly changing conditions of the marketplace. Cleveland firms often did not or could not respond with sufficient alacrity or astuteness to such changing conditions. Cleveland was perhaps too divorced from the center of the market in New York. It lacked a regional market of importance, and thus many manufacturers lost touch with what consumers wanted, and when the competitive price structure changed after World War II, some companies could not adapt to a shifting and rapidly changing marketplace. In the 1980s New York came to dominate the industry as both a marketplace and a manufacturing center, and substantial Cleveland manufacturers must constantly study and test the marketplace trends in New York City. In addition, there are other important regional markets, such as Dallas and Los Angeles, which served to move the focus of the industry away from Cleveland. Perhaps that is part of a larger underlying transformation of the American economy resulting in the loss of preeminence of the older industrial centers of the Great Lakes region and Middle West. On the other hand, Cleveland garment manufacturers who take advantage of new technologies, who learn to cut costs, and who learn to respond effectively to the marketplace may still survive and even flourish.

Stanley Garfinkel

Kent State Univ.

Residual Neighbors Jewish-African American Interactions in Cleveland From 1900 to 1970 by John Baden

(Masters Thesis-Jan, 2011)

Department of History, Case Western Reserve University

The original pdf is here (4.3mg download)

Introduction

This master’s thesis examines Jewish and African American relations in Cleveland, Ohio from 1900 to 1970. It argues that interactions between Jews and African Americans in the North have been forged by their history of shared urban space which fostered inter-reliance between Jewish entrepreneurs and their black customers. While this African American-Jewish inter-reliance has been explored in the context of civil rights, an examination of street-level interactions in shared urban spaces such as Jewish- run corner-stores, nightclubs, music shops, housing, and even criminal enterprises reveals that relations between African Americans and Jews have been driven as much by entrepreneurship, markets, and patterns of consumption as by their history as two oppressed peoples. Although this study focuses on Cleveland, it also illustrates some of the basic dynamics of demographic change and inter-ethnic activity in urban America during the twentieth century.

Economic cooperation and antagonism between African Americans and Jews have been critical to the history of U.S. cities. Since discrimination prevented most African Americans from opening their own stores, blacks heavily relied on Jewish-owned enterprises for groceries, housing, credit, leisure, and employment in many cities.1 Such

1 In 1920, 61.90 to 73.01 percent of Central Avenue grocers (the heart of Cleveland’s African American population) were Jewish, while Jews constituted about 9-12.5 percent of the city. For methodology on grocers, see footnote #48. This level of uncertainty for Jewish population data is due to the lack of Jewish population numbers for 1920. Instead, a range of 1918 and 1923 were used. There was also ambiguity in the Jewish population report if the numbers referred to Greater Cleveland or Cleveland proper which figured into the range presentedCleveland Directory Co., Cleveland City Directory [microfilm], (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications) and The Jewish Community Federation of Cleveland, “Estimating Cleveland’s Jewish Population 1979,” (The Jewish Community Federation of Cleveland,1980), in North American Jewish Data Bank, http://www.jewishdatabank.org/Archive/C-OH-Cleveland-1978- Estimating_Cleveland’s_Jewish_Population.pdf. Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, “Cleveland: A Bicentennial Timeline,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, http://ech.cwru.edu/timeline.html.

For other cities, see also Louis Wirth, The Ghetto (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997), 151. St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, “The Growth of a ‘Negro Market,’” in Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States, ed. Maurianne Adams and John H. Bracey

businesses provided needed services for the under-served urban African American community, and some like Record Rendezvous in Cleveland and the Chess Records in Chicago played a key role in the development and popularization of cultural expressions like jazz, rap, and rock ‘n’ roll. Other businesses, however, were known to exploit African-American residents, which led to mistrust, boycotts, and property destruction.

Jewish-African American relations in Cleveland began in earnest around 1890 as black migrants from the South and Jewish immigrants from Europe began to share neighborhoods in Cleveland’s near-East Side, especially in the section of town known as Central. Both communities came to Cleveland in hopes of economic advancement and to avoid persecution in their former homes. Once there, many Jews opened up stores in the Central neighborhood. After African Americans entered the city en masse during World War I, they became a crucial customer-base for these entrepreneurs. As Jews moved to better neighborhoods during the mid-1920s, they often retained stores in what were becoming largely African American sections of town. Meanwhile, persistent racism and a lack of capital prevented the overwhelming majority of African Americans from opening stores themselves. As a result, they continued to rely on Jewish-owned establishments for decades to come.

By the 1960s, nearly all of Cleveland’s Jews had moved into practically all-white suburbs, and the city’s black population found themselves abandoned in a city with

(Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 367. A footnote in this selection notes that 3/4ths of the merchants in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago were Jewish, but also notes that in New Orleans, “Italian merchants predominate.” Dominic J. Capeci Jr., “Black-Jewish Relations in Wartime Detroit: The Marsh, Loving, Wolf Surveys and the Race Riot of 1943,” in Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States, ed. Maurianne Adams and John H. Bracey (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 384, 393. This article notes that businesses damaged during the 1943 race riot predominately affected Jewish-owned businesses, and the large number of Jewish businesses in the riot area were a result of it previously being a Jewish neighborhood.

fleeting job opportunities and a diminishing tax base. Despite collaboration between African Americans and Jews to combat segregation and prejudice during this era, social and economic disparity ultimately fueled tensions between the two communities.

These tensions reached a boiling point in the late 1960s, and riots broke out in 1966 and 1968. During these riots, white owned businesses, including the dozens of Jewish businesses in African American neighborhoods were soft targets for rioters upset at the lack of social and economic progress in their communities. By the end of the decade, fear of unrest, rising insurance rates, a diminishing customer base, and an aging population of storekeepers caused many if not most of the businesses to close. By the end of the 1970s, hardly any commercial interactions persisted between Jews and African Americans in Cleveland proper.2

While this study primarily focuses on street-level interactions between African Americans and Jews, a separate activist relationship has existed between black and Jews since the turn of the twentieth century. Jews have historically played a disproportionate role in both funding and founding organizations like the NAACP, volunteering for black voter registration drives in the South, and providing legal support in landmark Civil Rights cases. The development of this “alliance” between Jews and African Americans and the tensions that it experienced from the late 1960s to the 1990s is the most researched aspect of African American-Jewish relations. There have been far fewer studies of commercial and lay interactions.

2 City Directory information shows that over 50 percent of grocery stores on Central Avenue closed between 1960 and 1970. Cleveland Directory Co., Cleveland City Directory [microfilm], (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications).

In 2006, The Cleveland Plain Dealer ran an article on Gordon’s Cycle Shop that referred to it as Glenville’s last Jewish-owned business. Michael Sangiacomo , “He’s not ready for cycle to end: Glenville bike shop owner continuing family tradition,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 26, 2006, in

Arnold Berger, “Gordon Cycle & Supply-The Last Jewish – Owned Business in Glenville,” Cleveland Jewish History, http://www.clevelandjewishhistory.net/glenville/gordoncycle.htm.

Three notable works about activism have been Cheryl Greenberg’s Troubling the Waters, Jonathan Kaufman’s Broken Alliance, and Seth Forman’s “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being Jewish (which became the basis for his book Blacks in the Jewish Mind).” Greenberg wrote that the purpose of her book was to “temper the idealized vision of perfect mutuality by demonstrating that blacks and Jews had different but overlapping goals and interests which converged in a particular historical moment [the 1950s-60s].”3 Kaufman’s work consists of several case studies that demonstrate what the author sees as the downfall of a African American-Jewish alliance. Like Greenberg, Kaufmann wrote that African American-Jewish collaboration was “rooted as much in the hard currency of politics and self-interest as in love and idealism,” and fell victim to “sleeping in the same bed, [but] dreaming different dreams.”4 Seth Forman’s 1997 article entitled “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being Jewish,” took a different approach. Forman argued that “the decision of the major Jewish organizations to pursue civil rights for all constituted a commitment to Jewish ‘otherness’ through liberalism,” and that supporting civil rights more than other whites “was one way of ensuring communal purpose and survival.”5

Other studies touch upon street-level interactions, but remain primarily focused on civil rights or urban demographic change as is the case with Beryl Satter’s Family Properties and Wendell Pritchett’s Brownsville, Brooklyn. Beryl Satter’s Family Properties addresses commercial relations in much more detail, but focuses on real estate exploitation and the author’s father, who was a civil rights activist. Other works like

3 Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century, Politics and Society in Twentieth-century America (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006), 1.

4 Broken Alliance: The Turbulent Times Between Blacks and Jews in America (New York: Scribner, 1988), 267- 268.

5 Seth Forman, “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being Jewish: Desegregation in the South and the Crisis of Jewish Liberalism (1997),” in Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States, ed. Maurianne Adams and John H. Bracey (Amherst:University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 631.

Wendell Pritchett’s Brownsville, Brooklyn analyzes neighborhood transition, but focuses on demographic change and community activism rather than residual businesses that remain in the neighborhood after it becomes predominantly African American.

One possible reason so many authors have shied away from discussing African American-Jewish relations in the economic sphere is that it is a sensitive topic for both communities. For centuries, Jews have been wrongly stereotyped as obsessed with money. During the 1960s and 70s, some African American activists perceived Jews as influencing too much control over institutions (from SNCC to liquor stores to record labels) that they feel should be controlled by their own community. One possible reason for the absence of more historical examinations of African American-Jewish commercial relations since the 1960s may be due to fears of re-opening these conflicts, and inadvertently adding to stereotypes of Jews as exploiters and blacks as violent. When asked about the role of Jews in rhythm and blues, producer Jerry Wexler (who has been credited with coining the term) responded, “That gets very hairy and I’d rather not get into that,” and “it opens up too many questionable areas, and I’m not going to fuck with that.”6 Wexler, had reason to remain silent. As New York Times journalist John Leland wrote in his book Hip: The History, that Wexler was hung in effigy at a 1968 black music conference, and believed “there was a plot to kill him to protest white control of the music business.7

Studies of African American-Jewish relations that have included economics have generally done so for the purposes of providing historical perspective for the various conflicts between the two communities, rather than as something that warrants study in

6 John Leland, 208. 7 Ibid., 208.

its own right. St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton’s 1945 book Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City analyzed the growth of what they called “the negro market,” and the trouble black businesses had with competing against white (mostly Jewish) establishments in Chicago. In wake of the 1943 Detroit riots, Wayne State University launched a study headed by sociologists, Donald C. Marsh, Eleanor Wolf, and Alvin Loving to investigate African American-Jewish relations, and determine if the riots that had burned many Jewish businesses were motivated by anti-Semitism. They concluded this was not the case.

Since World War II, discussion of African American-Jewish commercial relations has been sparse. Robert G. Weisbord and Arthur Benjamin Stein’s 1970 book, Bittersweet Encounter, included an exploration of African American-Jewish street level interactions, but once more dedicated most of its pages to ideological issues and points of tensions. As the book’s introduction notes, its purpose was “to provide a study which places contemporary Jewish-Negro relations in historical perspective; and hopefully to shed some light on an area of interracial relations that has already generated much heat and misunderstanding in recent years.” In 1985, historian Dominic Capeci re-examined the Marsh, Loving, and Wolf study, and supported its findings.

Jennifer Lee’s 2002 book, Civility in the City: Black, Jews, and Koreans in Urban America offers a sociological examination of contemporary inner-city retailers, primarily in Philadelphia and New York.8 Although the book is an excellent work of contemporary sociology, it fixes on one point in time and on cities which have vastly different histories than Cleveland or other Great Lakes industrial cities. In Cleveland, white flight has been

8 Jennifer Lee, Civility in the City: Blacks, Jews, and Koreans in Urban America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

more widespread, few Jewish businesses remain in black neighborhoods, and far fewer immigrant entrepreneurs have opened up inner-city retail businesses. Thus, it is crucial to carefully examine how ethnic relations have changed over time, and to account for regional differences within those changes. While this study focuses on Cleveland, it will explore similarities and differences with other cities across the United States.