Category: Amasa Stone

The Heart of Amasa Stone by John Vacha

THE HEART OF AMASA STONE

By John Vacha

On the afternoon of May 11, 1883, the usual decorum of Cleveland’s “Millionaires’ Row” was barely disturbed by a single muffled gunshot. It came from the rococo mansion of industrialist Amasa Stone. Entering an upstairs bathroom, a servant discovered the master of the house lying partly dressed in the bathtub, a .32 revolver by his side and a bullet in his heart. There were some unforgiving souls who thought it should have been done half a dozen years earlier.

One of his contemporaries was reputed to have predicted that while Stone may have been the richest man in the city, he would have its smallest funeral. He left an estate estimated at $6 million. His family, unwilling perhaps to risk fulfilling the second half of that prophecy, restricted his burial service at Lake View Cemetary to relatives only.

Except for one tragic miscalculation, Stone by most measures left behind a lifetime of enviable achievement. He had built and run some of Ohio’s principal railroads. His business ventures in railroads, banking, and manufacturing gained him one of the great fortunes in an age of great fortunes. Cleveland had gained its preeminent institution of higher learning largely at his behest, and his two daughters enjoyed well-connected marriages.

As did so many early Clevelanders, Stone came to the Western Reserve from New England. He brought skills highly in demand for a growing city, having experience in engineering and construction. In fact, there was already a job waiting for him in the Forest City.

Amasa Stone, Jr., was born in 1818, the ninth of ten children of Massachusetts farmers. Those siblings provided him with two rungs on what a nineteenth- century Currier & Ives print depicted as “The Ladder of Fortune.” He left farm work behind when seventeen to begin an apprenticeship in construction with his older brother, Daniel. Within two years he was able to buyout his apprenticeship and set about building homes and churches on his own.

By 1840 Stone joined his brother-in-law, William Howe, inventor of a unique bridge truss designed to support heavy loads over short spans. They employed it to construct the first railroad bridge over the Connecticut River. Stone soon purchased the patent rights to the Howe truss for all New England and corrected a suspected weakness in its design. His reconstruction of a hurricane-destroyed bridge across the Connecticut River in only forty days cemented his reputation as New England’s foremost railroad contractor.

Within another year, Stone was setting his sights westward beyond New England. He formed a partnership with Frederick Harbach and Stillman Witt to

build the northern half of the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad. It had been an ill- starred venture originally chartered in 1836 but almost immediately stunted in the cradle by the Panic of 1837. In order to keep their charter from being revoked, its directors at one point had resorted to the expedient of employing only a single worker with a shovel and wheelbarrow on the right-of-way.

Harbach, Stone, and Witt undertook to complete the troubled CC&C Railroad, taking part of their compensation in the form of stock. Because of the risk, they were able to demand a higher than normal fee, betting in effect on the road’s success and the resultant growth of Cleveland. The Cleveland to Columbus leg was opened on February 17, 1851. It proved an instant success and provided the basis of its makers’ fortunes.

“An industrial empire was in the making south of the Great Lakes; Cleveland was one of its centers; and Amasa Stone was one of the empire builders,” noted one historian. Stone was offered the position of superintendent of the CC&C at a salary of $4,000. He and his two partners then proceeded to build the Cleveland, Painesville, and Ashtabula Railroad, a job completed in 1852. Stone was a director on the boards of both roads and became president of the CP&A in 1857.

Stone had brought his family to Cleveland in the spring of 1851. With his wife, the former Julia Gleason, it included a son, Adelbert, and daughter Clara. Another daughter, Flora, was born shortly afterward. They became members of the prestigious First Presbyterian (Old Stone) Church on Public Square. In 1858 Stone manifested his position among the city’s elite by building an imposing new mansion on Euclid Avenue–one of the earliest residences on what would become nationally celebrated as “Millionaires’ Row.”

With all his construction experience, Stone naturally took a hand in the building of his own home. Underneath all the inevitable gingerbread of the Victorian era– bays and balustrades, corbels and belvederes–it rested on the Outer stolid, practical values of a self-taught engineer. Outer walls nearly two feet in width were insulated by an eight-inch hollow space between their inner and outer surfaces. A reputed 700,000 bricks went into the rearing of the structure. Running water, gas fixtures, and central heating were among its modern amenities. Stone’s library, dedicated more to business than to books, featured a fireproof recess for his desk, papers, and safe.

To all outward appearances, the Stone mansion conformed to the Italianate Villa style dominant along early Millionaires’ Row. A grand central hallway divided the formal from the family rooms, all finished with paneled ceilings, rosewood or oak doors, and fireplace mantels of Vermont marble. All was unveiled to the city’s fashionable set, and “old settlers” as well, at a housewarming hosted by the Stones early in 1859.

Stone meanwhile was broadening his business ventures in railroads and other fields. He built the Michigan Southern road, which was later linked with the CP&A as the Lakeshore Railroad. Together with several other business leaders he built the short but vital Cleveland and Newburgh line to service Cleveland’s burgeoning industrial valley. One of those nascent industries was the Cleveland Rolling Mill, in which Amasa was an investor and his brother Andros president. Amasa Stone also invested in the Western Union Telegraph Company being organized by Clevelander Jeptha Wade. He was a director of several banks and president of the Second National Bank, giving him an influential voice in the growth of the region’s industries.

By the time of the Civil War, Stone was clearly one of his city’s movers and shakers. Abolitionist in sentiment, he had supported the nomination of Abraham Lincoln by the Republicans in 1860. When Lincoln stopped in Cleveland on his way to Washington the following year, eight-year-old Flora Stone greeted the President- elect with a bouquet of flowers. With the coming of war, Lincoln turned to her father for assistance with problems of military supply and transportation.

On the home front in Cleveland, Stone joined a committee to distribute relief funds for the families of local Union volunteers. When recruiting fell off later in the war, he recommended that another committee be formed to raise $60,000 for bounties to encourage volunteers and thus spare Cuyahoga County from subjection to the military draft. He was an active supporter of Union candidate John Brough for governor in 1863, ensuring Ohio’s continued support for the war.

About the only thing Stone begrudged the Union cause was the service of his only son. Described as personable and unassuming, Adelbert Stone was an ardent Republican in sentiment with a strong desire to enlist in the Union Army. His father was grooming him for better things than cannon fodder, however, and decreed that “Dell” should go to Yale instead to study engineering. Weeks after the last guns of the Civil War were silenced, a telegram from Yale informed Stone of the death of his son. While on a geological field trip, he had drowned in the Connecticut River, scene of his father’s early exploits.

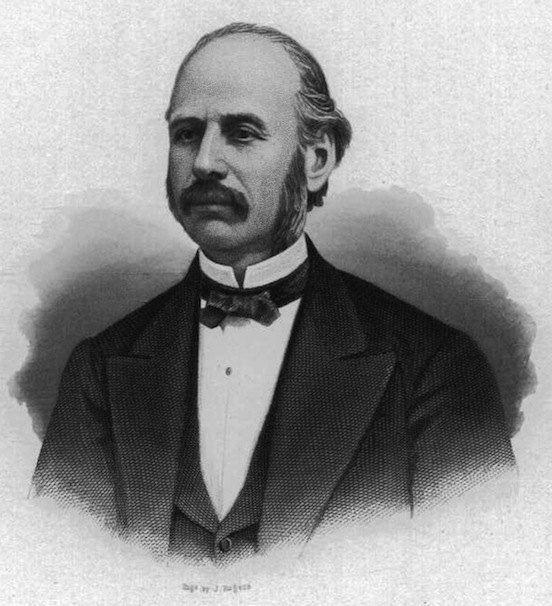

Of heavyset build, with a straight, well-formed nose and full mustache and beard trimmed to medium length, Stone projected an appearance that brooked no opposition. His eyes were deeply set under heavy brows and a receding hairline. “Stone was never constitutionally fit to accept domination for he considered dominion to be his own prerogative,” wrote his biographer. As president of the Lakeshore Railroad, he had insisted on using an iron Howe truss manufactured by the Cleveland Rolling Mill, to replace the bridge at Ashtabula. When advised by an engineer that the beams were inadequate for the length of the span, he got a new engineer and did it his way.

Stone’s leadership was evident in Cleveland’s civic as well as business affairs. He presided at the banquet to celebrate the opening of a new Union Depot on the lakefront, which he had helped design and build. He and Wade led in the incorporation of the Northern Ohio Fair Association to promote agriculture, industry, and, incidentally, trotting races. He joined other investors in the founding of the Union Steel Screw Company, which pioneered in the manufacture of wood screws from Bessemer steel. One of his principal charitable projects was the establishment of the Home for Aged Protestant Gentlewomen.

With the marriage in 1874 of his older daughter Clara, Stone acquired a son-in- law to compensate in part for the loss of his natural son. John Hay had already distinguished himself as a writer, diplomat, and secretary to Abraham Lincoln. Stone built a mansion for Clara and her husband next door to his own on Millionaires’ Row, telling neighbors with heavy-handed jocularity that he was “building a barn for his Hay.” Later Hay would employ the gift to host a celebrated reception for Ohio-born writer William Dean Howells, inviting his father-in-law to mix with such luminaries as President Rutherford Hayes and General James Garfield. Stone’s younger daughter Flora did as well as her sister, marrying the rising Cleveland industrialist Samuel Mather. Stone seemed to have scant social life outside of family and business, however. For the most part it consisted of quiet dinners and evenings with such neighbors and business associates as John and Antoinette Devereux.

Outside that close circle of family and friends, Stone cut a far from popular image in Gilded Age Cleveland. “Almost everybody feared Stone’s arbitrary ways, his harsh temper, and his biting tongue,” wrote the historian on Case Western Reserve University, who provided a possibly apocryphal but nonetheless revealing illustration. No love was lost between the sponsors of the originally separate institutions, Stone and Leonard Case, Jr. A single tract of land was to be divided between Case School of Applied Science and Stone’s legatee, Western Reserve College. Case preferred the western half, but knowing his antagonist, let out that he wanted the eastern section. The ploy worked: Stone insisted on the eastern half for Western Reserve, and Case thus acquired his real if unspoken preference.

One local businessman who managed to resist the habitual command of Stone was young John D. Rockefeller. Stone had been an early investor in Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company and a director of the Lakeshore Railroad when it granted Rockefeller secret rebates, which led to Standard’s dominance in the fledgling oil industry. As a member of Standard’s board, however, Stone assumed elder statesman airs which Rockefeller, twenty years his junior, found irksome. When Stone asked for an extension after letting an option to buy additional stock expire, Rockefeller refused to grant the favor. Thus affronted, Stone sold off his previous holdings; Standard survived and prospered nonetheless.

On top of that private rebuff, Stone suffered an even greater public humiliation. During a raging blizzard on the night of December 29, 1876, a westbound Lakeshore train approached the bridge over the Ashtabula Creek gorge — the same one Stone had built against the advice of his engineer. Only the lead locomotive made it to the other side. As the span collapsed, the second locomotive and eleven cars with 164 passengers and crewmen plunged seventy feet into what one newspaper headlined as “The Valley of Death!” Those not killed in the fall were exposed to fires started by the stoves in the passenger cars. Only eight escaped injury, and the death toll reached eighty-nine.

There were numerous post-mortems on the disaster. An Ashtabula County coroner’s jury, while paying lip service to his good intentions, placed primary responsibility directly on Stone. Also held responsible, for failure to adequately inspect the bridge, the Lakeshore Railroad was assessed for damages of more than half a million dollars. Another investigation was undertaken by a joint committee of the Ohio General Assembly. In consideration of Stone’s health, they questioned him in his personal library. Against at least one eyewitness account, Stone maintained that the bridge’s failure was due to the train’s derailment. The committee was less easy on the road’s chief engineer, Charles Collins, who had deferred to Stone on the bridge’s construction but admitted under intense questioning that he had never closely inspected the structure afterwards. Only hours after the hearing, the distraught Collins took a revolver and committed suicide. (It was the right thing to do, concluded many, but the wrong man had done it.) Stone, an object of general vilification, sought refuge in a trip to Europe.

Some believed that Stone had never recovered from the death of his son; most certainly, he never recovered from the opprobrium of the Ashtabula Bridge disaster. In addition to those afflictions, he was also plagued by business worries. Nationwide strikes broke out while he was in Europe, including employees of his Lakeshore Railroad. He couldn’t have been reassured by news from his son-in- law John Hay in Cleveland that “Since last week the country has been at the mercy of the mob. The town is full of thieves and tramps waiting and hoping for a riot, but not daring to begin it themselves.”

Following his return, Stone embarked on the principal benefaction of his civic career. In 1880 he offered half a million dollars to Western Reserve College in nearby Hudson, Ohio, on condition that the college relocate to Cleveland. He also called upon other Clevelanders to provide grounds for the campus. As a memorial to his son, he specified that the school should alter its name to Adelbert College of Western Reserve University, although the university historian, C.H. Cramer, speculated that the underlying real reason for the gift was “the necessity for some kind of propitiation” for the Ashtabula Bridge tragedy. Together with the simultaneous establishment of the Case School of Applied Science, Stone’s gift provided the foundation for what ultimately became known as University Circle.

Undoubtedly, the memorialization of his son was the last bit of satisfaction Stone was able to squeeze out of life. He had resigned from the board of the Lakeshore Railroad following its absorption by the Vanderbilt railroad interests, unable, as his biographer put it, to “withstand the transfer of major command decisions from Cleveland to the Vanderbilt offices in New York City.” Strikes had broken out at the Cleveland Rolling Mill in 1882, and several midwestern steel companies in which he was involved had failed. His health broke down completely under these stresses and whatever internal demons tormented him.

“I have not been to my office for some time,” Stone wrote to Hay, who was in Europe himself at the time. “Nervous frustration seemed to be my first misfortune and sleeplessness has followed.” Two weeks later, following yet another night of insomnia, he took his revolver into the bathroom and finally was able to find rest.

Stone’s widow and daughters devoted a considerable part of their inheritance towards redeeming the magnate’s reputation. Two years after his suicide, they donated John LaFarge’s Amasa Stone window to the restored sanctuary of Old Stone Church, following the fire of 1884. In 1910, the year the Stone mansion on Millionaires’ Row was torn down to make way for a Euclid Avenue department store, they provided for the erection of Amasa Stone Chapel on the campus of Western Reserve College, adjacent to the college’s Adelbert Main Building. From Stone’s old Union Depot, they salvaged a carving of Stone’s head and incorporated its stern image into the façade of the Gothic structure. They set it above the eastern portal, facing away from the old Case campus.

Amasa Stone aggregation

Amasa Stone Overview from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The link is here

STONE, AMASA (27 Apr. 1818-11 May 1883) was a contractor, railroad manager, financier, and philanthropist, born in Charlton, Mass. to Amasa and Esther (Boyden) Stone. He apprenticed in construction, and worked with his brother-in-law Wm. Howe to perfect the Howe truss bridge, buying the patent rights in 1842 and eventually constructing hundreds of bridges using his own improved design.

After building the Cleveland-to-Columbus spur of the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad, in 1851 Stone came to Cleveland to superintend the road and build the Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula. By 1852, he was a director of both roads; by 1857, he was president of the CP&A. He built or directed other railroads, including the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Road, taking part of his pay in stock, then investing his wealth as a major stockholder in Cleveland Rolling Mill and related mills throughout the country, as well as in several banks.

On 29 Dec. 1876, a Lake Shore Rd. Howe truss bridge collapsed at Ashtabula, plunging a train into a ravine, killing 92. An investigation implicated Stone who, ignoring engineers, had used an overly long span. The road’s chief engineer, Chas. Collins, committed suicide. He was also vexed by William H. Vanderbilt’s 1883 plan to consolidate the Lake Shore Rd. with the NICKEL PLATE ROAD. On 11 May 1883, after several steel mills he controlled failed, Stone committed suicide, leaving a wife, Julia Gleason Stone, 2 daughters, Clara Stone Hay and FLORA STONE MATHER†. His multi-million-dollar estate included a $100,000 bequest to Western Reserve University. In 1881 Stone had donated $500,000 to WRU to establish Adelbert College in memory of his son, who had died in a swimming accident at Yale in 1866. He was buried in LAKE VIEW CEMETERY.

Bankrolling Higher Learning Philanthropists’ Feud Led to Founding of Two Schools

Plain Dealer article written by Bob Rich and published on February 4, 1996

BANKROLLING HIGHER LEARNING PHILANTHROPISTS’ FEUD LED TO FOUNDING

OF TWO SCHOOLS

On a bitter, cold February day in 1851, a brightly polished new locomotive pulled into Cleveland packed with passengers from Columbus and Cincinnati to celebrate the completion of the city’s first railroad, the Cleveland-Columbus-Cincinnati Co.

Among the officials who greeted the out-of-towners on the courthouse steps were the mayor, William Case, and the superintendent of the railroad, Amasa Stone, who not only had stock in the line, but a salary of $4,000 a year to run it.

These two were to clash in later years, and their mutual dislike and competitiveness would strongly affect higher education in Cleveland.

The famous and accomplished Case family: father, Leonard, and sons, Leonard Jr., and William, were unquestionably the first big names in 19th century Cleveland education, starting with the Cleveland Medical College in 1843. They also made several tries to create a Cleveland university, but came up short in the money department each time.

When Leonard Case Jr. died in 1880, he accomplished by his bequest of $1 million in land and money what he couldn’t manage while alive: a successful new school of higher education – the Case School of Applied Science, on Rockwell Ave. It was the first independent school of technology west of the Alleghenies.

The Cases were doing their business friends a favor because industry had become complicated; special skills were needed, and the idea was that sons of middle-class families could afford to give up working for wages while they studied for better jobs. As for the sons and daughters of Cleveland’s elite, they would continue to be taught liberal arts at tiny Western Reserve University in Hudson, Ohio.

But that school was practically broke, and so the trustees were perhaps more than willing to be lured away to University Circle in Cleveland by that man whose personality was as flinty as his name – Amasa Stone.

Stone’s arrogance had made him unpopular even in his own top-drawer society circle. But it also drove him as a philanthropist to do things for which only he would get the credit – and that included competing with the Cases by bankrolling a successful university in Cleveland.

Stone had made a phenomenal climb to wealth and power since those early railroad days. From banking to contracting, from a rolling mill to screw manufacturing, even to a trotting track in Glenville, Amasa Stone was in the thick of it. He gave the Home for the Aged Protestant Gentlewomen to the YWCA, saw his two daughters married extremely well – Clara to John Hay, a famous diplomat, writer and secretary to Abraham Lincoln; and Flora to industrialist Samuel Mather.

But tragedy dogged him: his son, Adelbert, was drowned in a swimming accident at Yale. He lost his reputation when a train on one of his own lines plunged into the Ashtabula gorge during a snowstorm in December 1876, killing 92 passengers and injuring more. The main arch of the bridge had caved in – a wooden bridge, designed, patented, and built by Stone himself, against the advice of his own engineer who wanted a new stone or iron bridge to span the gorge.

His physical and psychological health was already bad by 1880, when his business empire began to collapse; only philanthropy relieved some of the pressure.

Stone offered the little Hudson college $500,000 if it would move to what is now the University Circle area. There were conditions: he wanted the school named for himself, (but had to settle for Adelbert College of Western Reserve University); wanted to design and construct the buildings; Cleveland citizens had to provide the land for the site; and the site had to be built next to the new Case School, which had bought some farmland east of Euclid Ave. and E. 107th St.

Leonard Case Jr. may have been dead, but Amasa Stone was still competing with the family name. The little Hudson school lunged at the offer. As a local writer put it, according to historian William G. Rose, they “hitched their educational wagon to the new star of progress and threw old-fashioned prudence to the wind.”

A depressed Amasa Stone commited suicide in 1883, but his youngest daughter Flora and her husband, Samuel Mather, would help more than 30 religious, charitable and educational institutions in their time, including establishing the women’s undergraduate school at Western Reserve.

And Florence and sister Clara were able to honor their autocratic father with the Amasa Stone Chapel.

There was one thing he wanted that he didn’t get: a demand that the two schools exist side-by-side “in close proximity and harmony.” The two institutions promptly built a fence between them.