CLEVELAND: ECONOMICS, IMAGES, AND EXPECTATIONS by Dr. JOHN J. GRABOWSKI

INTRODUCTION

Why do cities grow, thrive, and sometimes fail? What holds them together and makes them special places—unique urban landscapes with distinctive personalities? Often we fix on the “image” of a city: its structural landmarks; the natural environment in which it is situated, or the amenities of life which give it character, be they an orchestra or a sports team. Even less tangible attributes, including a reputation for qualities such as innovation, perseverance, or social justice, come into play here. Image, however, is often a gloss, one that hides the core of the community, the portion of its history that has been central to its existence. Many would like to see Cleveland, both now and historically, as a “city on a hill,” one defined by many of the factors noted above. Yet, Cleveland’s image is to an extent a veneer. Underneath that veneer is the economic core that led to the creation of the city and that has sustained it at various levels for over 200 years. Without it, the veneer would not exist. The fact that today, aspects of Cleveland’s veneer have merged into its economic core represents a remarkable historical transformation.

Cleveland’s Public Square is perhaps the best place to begin in examining the history of Cleveland and the interrelationship between economic reality and image. On the northwest quadrant of the square a statue of Tom L. Johnson reminds one and all that Cleveland was in the forefront of the Progressive movement at the turn of the twentieth century. Johnson, whose governmental reforms led to his characterization as the best mayor of the best-governed city in the United States, symbolizes so much of our civic patina—well-organized progressive improvements ranging from the chlorination of water to the creation of what is now United Way.

Just to the north of the Johnson statue is the First Presbyterian (Old Stone) Church, a monument to the role that religion has played in regional history, from its involvement in the anti-slavery movement to the establishment, by various religious groups, of orphanages, educational institutions, hospitals and hundreds of other charitable endeavors.

Looking toward the east from the Johnson statue one can see the south end of the Mall, a landmark of the national city beautiful movement, and the Metzenbaum Courthouse, a reminder of justice and jurisprudence in the community. Slightly to the south, on the southeast quadrant stands the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, testimony to the role northeastern Ohio played in the American Civil War, one in which the community’s core beliefs, ranging from those relating to what we now call social justice to the place of private charity in times of crisis and need, were as important as its military and economic contributions.

In one sense, a good quick look at the Public Square indicates that Cleveland is a special place—and, indeed, in many ways it is. Some may want to think that it is indeed a city on a hill, an example for others. That, perhaps, it has been and continues to be. But, as we complete our visual circuit by coming to the southwest quadrant, we are brought back to the founding reality of the community. There stands the statue of General Moses Cleaveland, the revered founder of the city that bears his name. He stands tall, staff in hand, the archetypical colonial father figure. Yes, he was the community’s founder and also a Revolutionary War veteran and a lawyer. That we remember, but what we often forget is that Cleaveland was also an investor. He was one of fifty-six members of the Connecticut Land Company whose interest in Connecticut’s Western Reserve was predicated on profit rather than altruism. Cleaveland’s intent in coming to the city that now bears his name was not to settle, but to survey. Cleaveland and the partners in the company had purchased 3.4 million acres from the state of Connecticut. That land, its “Western Reserve” was a remnant of its old colonial claims that it managed to retain after the formation of the United States. Stretching 120 miles west from the border of Pennsylvania, it constitutes much of what we consider today as northeast Ohio.

Surveying was the first step in making what was wilderness into a marketable commodity. Cleaveland would return to Connecticut some three months after his arrival at the mouth of the Cuyahoga, sanguine about the company’s ability to make a profit from its investment. The Public Square upon which these observations are focused was part of the profit scheme—a communal commons, grazing land for the animals of the first settlers and a nice touch of home, since the town commons was so much a part of the New England heritage of Cleaveland and those he expected to follow him as purchasers rather than sojourners.

FROM REAL ESTATE VENTURE TO MERCANTILE CENTER TO INDUSTRIAL METROPOLIS 1796–1920

Moses Cleaveland’s expectations for the community that bore his name (his surveying crew named it in his honor in 1796—its spelling would later be simplified to Cleveland) went unfulfilled for nearly two decades. Indeed, the real estate venture of the Connecticut Land Company did not meet its investors’ immediate expectations. Land in the Connecticut Western Reserve sold slowly and settlement in its “capital” Clevealand languished for over two decades. It appeared that all had overlooked a number of critical economic and business factors. There was no easy way to get to the Reserve from the eastern seaboard and, indeed, there was better, more accessible open land along the way, mainly in western New York state. Then too, there were questions about the legal title to the land. Moreover, there were lingering fears that the British (just across Lake Erie in Canada) might try to reclaim the trans-Appalachian west from the recently independent United States. Cleveland had an additional problem—the lands near the mouth of the Cuyahoga river were infested with mosquitoes. Those who attempted to settle in what is now the Flats came down with malaria and soon moved away to higher lands east of the small settlement. The sales situation became so desperate that Oliver Phelps, one of the prime investors in the venture, nearly ended up in a debtors’ prison.

It would be easy to accuse the investors of a lack of foresight and planning. Indeed, that was somewhat the case. The company built no roads to provide easy access to the area nor did it provide for any of the basic amenities of life. It simply surveyed and sold the land. Buyers were on their own after they made their purchases. Yet, two of the investors’ core beliefs about the land were correct. They knew that there was a huge desire for better land among people in New England and that this desire would continue to grow as the population expanded. They also knew that water was a key factor in colonial settlement—not only for growing crops, but even more importantly for transportation. Waterways, natural and manmade, were the best and cheapest means of transport for people and goods at the turn of the nineteenth century. Cleveland had that advantage and indeed, George Washington and Benjamin Franklin had identified the site on the shore of Lake Erie as one of commercial and strategic importance.

Eventually, when issues of land title were cleared and when the end of the War of 1812 calmed fears regarding any future British invasion, the settlement of Cleveland accelerated. In 1820, 606 people lived in a community that had had a population of only 57 a decade before. Ten years later, in 1830, the population was 1,075. More importantly, by that time Cleveland was at the northern end of a major public works project, the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Begun in 1825 and completed in 1832, the canal connected Cleveland, on the shores of Lake Erie, to Portsmouth on the Ohio River. More importantly, this was but one link in a global chain of waterways that stretched from European ports to New York and then via the Hudson River and the Erie Canal to the Great Lakes. From Portsmouth, trade continued via the Ohio River to Cincinnati, St. Louis, and eventually New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico.

Investors and entrepreneurs quickly realized that Cleveland presented enormous opportunities. It became a transshipment point for manufactured goods from Europe and the eastern US to the rapidly developing Midwestern frontier. It also was a point where commodities produced on the farms in the Midwest could be purchased wholesale and then brokered to buyers in Ohio and the East. What Moses Cleaveland had envisioned as a mercantile town serving farmers and farm communities in the surrounding area soon became a mercantile town with trade extending far beyond the immediate hinterland. The ways in which location and transportation spurred economic growth were multiple. As the population continued to increase, land prices in the city rose and land speculators prospered. Builders and tradespeople arrived to serve the community’s needs and artisans and laborers came to make consumer products and to take on the heavy work of unloading and loading boats and clearing additional land. Farmers also settled in areas that are now a part of the twenty-first century city’s suburban landscape. While the earlier settlers were mostly from New England and New York, those who followed, beginning in the 1820s, were in large part immigrants from Europe. By 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, Cleveland had a population of 43,417, of which over 40% was of foreign birth, largely from Ireland, the British Isles and the German states and principalities.

New migrants to the city, whether from abroad or the rural hinterlands, supplied not only labor and skills, but often brought with them ideas that would continue the transformation of the community. Several deserve to be singled out because of their impact on the area’s economic development.

Alfred Kelly, a lawyer who migrated from New York in 1810, played the principal role in advocating for the Ohio and Erie Canal and overseeing its construction. As noted earlier, that project positioned Cleveland for growth on a scale far beyond that expected by its founders. The potential of the community attracted young entrepreneurs, one of them being John D. Rockefeller, who moved to the area in 1853. Following his graduation from Central High School he attended a local business college and then became a bookkeeper in a commodities house. With its canal and lake transport systems, and, by the 1850s, a growing network of rail connections, Cleveland had evolved into a major trading center for grain, cloth, salt, and various other commodities central to life in the mid-nineteenth century. Rockefeller would eventually become a partner in his own commission house just before the Civil War. That conflict, which vastly increased the need for commodities, such as food, wood, and wool, provided the basis for his fortune, a fortune that increased exponentially when he began to deal with a new commodity, oil.

Rockefeller’s interest in oil can be seen as one of the key moments in the area’s transformation from a mercantile to an industrial city: that is, from an economy in which goods are bought and sold, to one in which they are manufactured. Central to that transformation were new, disruptive technologies. Key among them were railroads. Railroads freed the economy from dependence on water transport (which was unusable in the winter) and poor roads and inefficient horse and wagon transport. It was a railroad linking Cleveland to the oil fields of Pennsylvania that helped to make Rockefeller’s new industry possible, along with the development of new methods to “crack” raw petroleum by separating it into constituent components such as kerosene and paraffin, each of which provided important new fuels for lighting. The need for sulfuric acid in the cracking process lured chemist Eugene Grasselli to Cleveland in 1857, thus laying the basis for a chemical industry that would later make possible the paint and varnish manufacturing companies led by Henry Sherwin, Edward Williams, and Francis Glidden.

The rail network, which expanded enormously in the 1850s, allowed two other migrants to further transform the economy. David and John Jones had learned ironworking in the Dowlais Mill in Glamorganshire, South Wales. They brought their skills to the United States, first practicing their trade in Pennsylvania. In 1857 they opened their own mill in Newburgh, just southeast of Cleveland. The mill was situated along the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad, which provided access to coal from southern Ohio and iron ore from the upper Great Lakes region via the port of Cleveland. The growing needs of the railroads for iron rails and other iron products was central to the economic equation that linked immigrant skills with raw materials and transportation.

As was the case with Rockefeller’s commission business, the Civil War served to catalyze industrial development in Cleveland. It also created a cadre of very wealthy individuals whose political and economic influence over the community would continue for decades. Crisfield Johnson in his 1879 history of Cuyahoga County succinctly noted: “…the war found Cleveland a commercial city and left it a manufacturing city. Not that it ceased to do a great deal of commercial business, but the predominant interests had become the manufacturing ones.” During the war the city’s population increased by nearly one third, from 43,417 in 1860 to 67,500 in 1866.

Industry would become Cleveland’s raison d’être during the post-Civil War period and remain at the core of its economy for nearly a century. The patterns of migration and entrepreneurship evidenced in the years before the war would be replicated and multiplied decade after decade. New products—nuts, bolts, screws, sewing machines, bicycles, automobiles, and even aircraft—would be flowing from the city’s factories by the 1920s. New disruptive technologies, such as electrical power would challenge old and established ones as inventors such as Charles F. Brush created dynamos and electric arc lighting for the city. As industry grew to dominate the economy, it also drove the concurrent development of banking and corporate law.

The city’s post-Civil War industrialization coincided with major changes in migration patterns, both globally and within the United States. By the 1880s the predominant movement out of Europe had shifted from the northern and western parts of the continent to the central, eastern and southern sections. Cleveland, which had begun to diversify from its New England roots with the addition of Irish, German and British-born individuals to its population in the years before the Civil War, now saw the arrival of Poles, Hungarians, Italians, Slovenes, Croatians and dozens of other nationalities and ethnicities to its population. By the mid-1870s, the equality that had been promised to freed African-Americans in the post-war South had been replaced with new forms of oppression and economic hardship. They began a mass movement out of the South known as the Great Migration during the latter years of the nineteenth century arriving in northern industrial cities at the same time as thousands of European immigrants. What Cleveland offered, as did many other industrial cities in the north, was economic opportunity and the promise of equality.

The labor needs of the city’s growing industries were huge. By 1920 they employed 157,730 people and produced products valued at over one billion dollars. Cleveland’s industrial production ranked fifth among American cities and, coincidentally, its population of nearly 800,000 ranked it fifth as well. Of that population, two thirds were of foreign parentage or foreign birth, representing twenty-nine distinct nationalities. This transformation had occurred, essentially, in one century, from 1820 to 1920.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF UNEXPECTED CHANGE AND THE CREATION OF IMAGE

By 1920 Cleveland already had in place many of those attributes that now comprise part of its contemporary image. It had established major cultural institutions including the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland Orchestra. It had begun to address environmental issues with a growing system of parks and parkways. Its Community Chest, the forerunner of United Way, had unified and systematized charitable giving, and the Cleveland Foundation, the first community trust in the world, served as a paradigm for modern philanthropy. Within the realm of education, its public school system was well on its way to national recognition, and Western Reserve University and the Case School of Applied Sciences anchored the academic-cultural district that had become known as University Circle. Its system of government and the manner in which government worked with business was viewed as a progressive model for the nation, one that had created the Group Plan of public buildings and had, after some contention, modernized and systematized its urban transit system.

All of these markers of civilization and forward thinking were consequences of the enormous changes the community had undergone in the previous century. They came about both because the wealth generated during that period supported their creation and, in many instances, because they addressed major social and economic issues that arose in the wake of industrialization. If many of the inventions and industrial processes that moved Cleveland forward could be viewed as disruptive in the technological sense, so too were their effects on the community. Equally disruptive was the rapid growth in population and size of the city — far beyond that which had occurred in the eighteenth century. Compounding all of this was the diversity of the population. The only tools the community had at hand to deal with such issues in the early years of change were those that derived from the social and religious structure of the relatively homogeneous pre-industrial communities of colonial America.

When the community began to expand during the 1820s and 1830s it turned to such traditional systems to deal with issues such as poverty, health care, the need for public education, and general civic well-being. Those systems, in substantial part, were carried over within the New England model on which the city was based. Charity, for example, emanated largely from the church. Later, as was usual in early America, a community poorhouse was opened to house the indigent. It was one of the few governmental contributions to what we now call social welfare. But as the city grew larger and, importantly, religiously and demographically diverse in the 1840s and 1850s, the problems grew both in scale and complexity. Orphan homes, which became common in the nineteenth century (replacing the tradition of relatives taking in children) multiplied: not only because of a larger number of orphans but also because of religion. By the 1860s Cleveland would have separate agencies for Protestant, Catholic and Jewish orphans. When it became necessary to take care of the elderly, the poorhouse, which had in part taken the place of the family, was augmented and eventually replaced by homes for the aged. In Cleveland, these were subdivided by religion and ethnicity. By century’s end the city had homes for the Protestant, Catholic, African-American, Scottish, German, and Jewish aged.

Continued growth and diversification of population also challenged established forms of community governance. Cleveland, which officially became a village in 1815 and then a city in 1836, was bound by state regulations in regard to how it could structure its government. The state-dictated structure was ideal for small communities, but not flexible enough for growing urban centers. As the city expanded in the years after the Civil War, it struggled to accommodate growing needs for police and fire protection, for adequate operating revenues, and for a truly representative legislative structure within the bounds those regulations imposed. By the end of the nineteenth century many saw Cleveland, and other growing industrial communities, as divorced from the rurally focused state government.

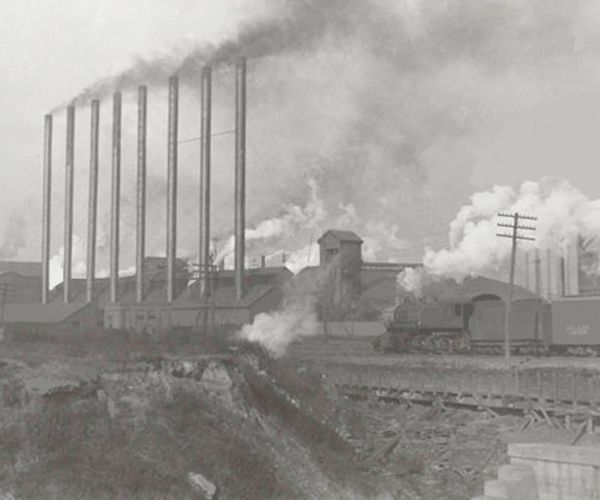

Growth also had severe consequences for the environment. The city’s waterfront was given over to the railroads in the 1850s; its river became a convenient dumping ground for industrial waste products. In 1881 Mayor Rensselaer Herrick characterized the Cuyahoga River as “an open sewer through the center of the city.” The lake, which comprised the chief source of drinking water, became increasingly polluted — so much so that by the early twentieth century the water intake had to be placed 26,000 feet offshore to insure a clean supply of water. Within the city living conditions worsened as migrants and immigrants arrived in ever larger numbers. The city’s population would, for example, more than double in the twenty years between 1900 and 1920. Although part of the increase came through the annexation of surrounding communities such as Glenville, the bulk was from in-migration, which put a severe strain on housing and infrastructure such as water and sewers. The Haymarket and Lower Woodland, two areas close to the central city, were not only severely overcrowded, they were environmental wastelands. Yards and parks were nearly nonexistent. Outdoor privies remained the rule and bathing facilities were rare—in the sixteenth ward, home to 7,728 people, there were only eighty-seven bathtubs. One immigrant Italian mother, upon being given flowers by a social worker, noted that they were the first she had seen in America. Perhaps that was an overstatement, but it was nonetheless true that Cleveland, which had prided itself on being called “the Forest City,” had in fact been losing many of its trees to airborne pollution for years. The quick and easy solution was to replace the trees with hardier species and not to deal directly with the main issue. At this point in the city’s history, the need to do business trumped all calls for smoke abatement or ending the use of the river as a disposal system for local industry.

Beyond these specific issues, perhaps the overriding consequence of the city’s rapid growth was the challenge it presented to the sense of Cleveland as a single community. That it had been, albeit for a relatively short period in the early 1800s, but by the 1840s there were already divisions. As industry and commerce grew the Flats, that area along the river became the least desirable residential area in the city. Known as the “under the hill” district, it was home to the poor, a number of whom were Irish Catholics. The houses of the wealthier residents, in contrast, were located on top of the hill in what is today’s Warehouse District. A separate city, the City of Ohio, existed across the river valley, a fairly formidable obstacle to cross at that time.

The situation would be far more complex by the early 1900s. Dozens of migrant and immigrant neighborhoods grew up around the manufacturing plants in which the immigrants worked. The plants generally were sited on the rail lines that spread away from the central city In an era before cheap, relatively quick public transportation became available, people lived where they could walk to work. Migration chains created a preponderance of one nationality or another in these areas. The neighborhoods were largely self-sufficient, with their own churches or synagogues, and stores selling familiar goods in which the owners spoke the language of the district. Cleveland was, in reality, a series of communities defined by ethnicity, religion and economic status, and the communities’ names — Karlin, Warszawa, Praha, Dutch Hill, Little Italy, Big Italy, Poznan — testified to their particularistic identities. To many observers, they were foreign entities sitting within an American city.

These factory neighborhoods existed in stark contrast to Euclid Avenue, whose mansions housed the individuals made wealthy by the burgeoning industrial economy. The homes on Euclid Avenue stretched for miles, from the eastern edge of downtown nearly all the way to University Circle. A youngster from the lower Woodland Avenue immigrant neighborhood marveled at the structures when he was on a field trip sponsored by a local social settlement. He thought the houses were all schools, since the only building he knew of that rivaled the homes in size was his school.

Underneath these very visible differences was a major fault line, one which stretched through every industrial city in the United States. It was the line that divided labor and capital. Beginning in the 1870s, Cleveland witnessed a number of strikes, many accompanied by violence. Workers at Rockefeller’s Standard Oil refinery struck in 1877. Two violent strikes occurred at the Cleveland Rolling Mills in 1882 and 1885, and in 1899 troops were called out to control a strike on the city’s streetcar lines. Such struggles over the rights of labor and capital usually had political overtones, with some individuals advocating governmental and economic solutions from outside the American system. Socialists and anarchists were involved in the Standard Oil and Rolling Mill strikes. Indeed, there was a growing “radical” segment in the city’s population. Charles Ruthenberg ran credible campaigns for mayor as a Socialist. Socialists in the Czech community established a newspaper, a summer camp, and a gymnastic organization. A young, mentally unbalanced Polish-American from the Warszawa neighborhood, Leon Czolgosz, fancied himself an anarchist and in 1901 assassinated President William McKinley. Events such as these unnerved many Clevelanders and raised the specter of a social revolution. Indeed, one Clevelander wrote a novel, The Breadwinners, which focused on a labor revolt in the mythical city of Buffland. The author was John Hay, a former secretary to Abraham Lincoln, and the husband of Clara Stone, a daughter of railroad magnate Amasa Stone. Like his in-laws, he was a resident of Euclid Avenue.

RESPONDING TO CHANGE, CREATING THE MODERN INDUSTRIAL CITY

Cleveland was not alone in confronting the consequences of industrialization. It was a national crisis. Excesses of wealth characterized the American Gilded Age. Labor violence, poverty, and a sense of a lost national identity were hallmarks of the period from 1870 to World War I. Historian Robert Wiebe has characterized this period as one in which Americans engaged in a “search for order” — that is, ways to create cohesion within a geographically huge and increasingly diverse nation-state and to make rapidly evolving systems of charity and governance, as well as emerging professions, more orderly. What is remarkable about Cleveland is the manner in which it pursued its own search for order. Its success in coming to terms with the new “urban normal” during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was nationally recognized then and today. That success remains part of the city’s image.

As was the case in its industrial development, several individuals can be seen as representative of the city’s approach to reform in what we term the Progressive Era.

The pivotal figure is Tom L. Johnson, whose statue, as noted at the beginning of this essay, now stands on the city’s Public Square (a second statue of Johnson can also be found on the grounds of the Western Reserve Historical Society). Johnson was an entrepreneur and his interests lay in urban transportation. He was one of many individuals who capitalized on the need to provide effective transportation in America’s growing cities. That transport took the form of street railways—initially horse drawn, then cable driven and finally electrically powered. By the time he arrived in Cleveland around 1883, Johnson had become wealthy through investments in street railways around the country—possible at that time, since such enterprises were private, not municipal. It was a lucrative but often shady business, for entrepreneurs such as Johnson needed to secure legislative permission to build and operate street railway franchises. That permission often came only after bribes were paid and deals were struck with the right politicians. Johnson could work the system as well as any man — and he became very wealthy doing so. But Tom L. Johnson had what might be called a conversion experience, and as a consequence he became an outspoken advocate of reform. He read the works of the single-tax reformer Henry George and began to question the system that had made him wealthy. He entered politics in order to effect the reforms he believed in. He served two terms in the US House of Representatives and in 1901 became the major of Cleveland, serving in that office for eight years.

Johnson worked to secure the municipal ownership of utilities, including urban transit, and he espoused the concept of professionalism in governance. He filled his mayoral administration with people who had expertise as managers, rather than political connections. His appointees included a young lawyer from West Virginia, Newton D. Baker, and Peter Witt, a former foundry worker and union advocate. Together, Johnson and his cabinet reformed the police force, modernized the water supply system, updated the prison system, and forwarded the cause of municipal ownership. He constantly challenged the state-mandated structure for municipal governance and pushed for home rule—that is, the right of a city like Cleveland to structure its own government to best meet its needs. Nationally recognized journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote, “Johnson is the best mayor of the best-governed city in America.”

While Johnson often offended the wealthier segment of the population, a group to which he belonged and with which he associated, that segment of the population was nonetheless also moving toward reform, most notably in the area of philanthropy. As wealth grew in the city in the mid-nineteenth century, those who had acquired it often donated some of it to benefit the community. Much of this followed in the tradition fostered by the religious groups to which the wealthy belonged. However, the scope of their gifts far exceeded what had once been considered as normal charity. John D. Rockefeller, a Baptist, was a prime example. He began to make charitable donations from the time he received his first pay as an employee of the commission merchants Hewitt and Tuttle. As he grew wealthier his gifts increased in both number and size. Eventually, his fortune would become the basis of a foundation that systematized the distribution of funds. Unfortunately, he was by that time no longer a full-time resident of Cleveland. Other similar, individual charitable endeavors were numerous. Jeptha Wade gave part of his private parkland to the city. William J. Gordon did likewise. Members of the Severance family helped create the rich cultural life that the city still enjoys through their donations to art and music. The Mather family was at the forefront in the support of higher education at Western Reserve University, health care at what would become University Hospitals, and assistance to the inner city with gifts to settlement houses such as Hiram House and Goodrich House. Those who had achieved wealth and status supported the increasing needs of the city, be they educational, social welfare or cultural. While some of these gifts derived from the particular donor’s religious affiliation and beliefs and others from a particular cultural avocation, such as music or fine art, all were given in a time before tax deductions provided a fiscal reward for personal altruism.

Yet, the needs of the city were so vast that the wealthy felt hard pressed as to where to place their benevolence. Judgment as to what was worthy, effective, and legitimate needed to be made when request after request came to the doors on Euclid Avenue. A system was needed—and Cleveland’s leading industrialists and entrepreneurs were strong advocates of rationalized processes of production and what would become “scientific management.” They would apply that mindset to charitable giving as well, and in doing so create another historical landmark for the city.

This drive for efficiency in production and modernization in industrial processes was strongly reflected in the city’s Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber, as a modern progressive body, helped transform the city as much as did Johnson’s administration. The Chamber served as the principal advocate for foster economic growth in Cleveland, and its minute books from the early twentieth century indicate how rationally and methodically it approached this goal. But the members of the Chamber also realized that business could not prosper in a community that was not healthy, cohesive, and politically stable. They needed to provide a viable alternative to counter proposed solutions such as socialism. To this end, they proceeded to attempt to organize, stabilize and regularize the workings of the often chaotic city. The Chamber’s Committee on Benevolent Associations, established in 1903, would develop into the Community Chest and eventually the United Way campaign, which unified charitable giving and also rationalized (through the Cleveland Welfare Federation) the distribution of the funds it raised. In addition, the Chamber created the basis for housing code legislation which would help end overcrowding and shoddy construction. Its activities also encompassed a committee to study the need for bathhouses in an inner city largely devoid of indoor plumbing.

Although often violently in disagreement, the businessmen represented by the Chamber and the Johnson administration often shared goals. Certainly, business interests fought Johnson on the issue of municipal ownership. Indeed, Johnson’s ardent support of municipal transit and the staunch opposition to it would cost him his mayoral career and even arguably lead to his early death. Yet, the desire on the part of both parties to find a workable solution to the problems of the industrial city often placed them in partnership. The Group Plan, which resulted in the construction of the Mall (which replaced a decrepit section of the city with a nationally significant grouping of public buildings), was one such example, as was the desire to replace politicians in municipal administrative positions with experts who could rationally manage the functions held by the government. This alignment between sometimes starry-eyed political reformers and the business community of Cleveland has endured, albeit with some rough passages, for over a century.

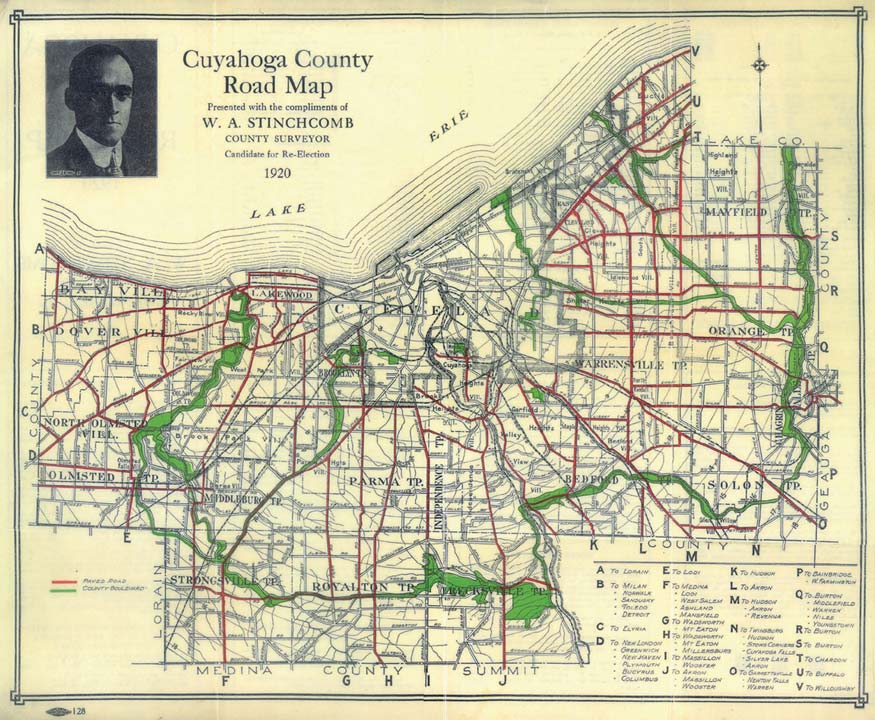

Recognizing this drive for a system to manage the urban city provides the key to understanding what happened in Cleveland at the turn of the twentieth century and during the next two decades. One can find examples of Taylorism, or scientific management, everywhere. Frederick Goff, a banker who played a leading role in establishing the Cleveland Trust Company through the consolidation of an assortment of regional banks, also rationalized the system of philanthropic bequests. His Cleveland Foundation set a standard for melding multiple bequests into an independently administered fund that could be used to deal with larger issues and to insure that those funds met the needs existent at any given time within the community. William Stinchcomb, http://www.aapra.org/Pugsley/StinchcombWilliam.html an engineer for the city’s Parks Department, took a holistic view of parks and created a unified system now referred to as the Emerald Necklace, a series of parks encircling the Cleveland area. Even social work, once the purview of individuals with a strong desire to help their fellow citizens, became regularized when Western Reserve University established its School of Applied Social Work to train those who wished to serve.

It was with these systems — a rationalized approach to civic issues and a public-private partnership—that Cleveland entered the 1920s. Implicit was an assumption that the industrial economy upon which the community had built its own city on a hill would endure. However, within four decades, that notion would, as was the case with the assumptions made by Moses Cleaveland and the early pioneers, be tested by the development of unforeseen economic changes— in this instance the development of a truly globalized economy.

MANAGING LEGACY AND LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

In 2009, a century after the height of the Progressive Era reforms, Cleveland, with an estimated population of 431,363, ranked as the nation’s 43rd largest city, two steps above its rank in 1840, when it had been the country’s 45th largest city. Its primary employment areas were in health care, research and the service economy. Industry, while still apparent, was no longer the key economic underpinning of the city. Ranked among the most poverty-stricken areas in the nation and characterized by a problematic racial divide, it seemed that the city had moved back in time rather than forward. What had happened — how had the Progressive reformers followed Moses Cleaveland in misinterpreting the community’s future? Or had they?

It can be argued that by 1920, the community’s industrial era had only one more decade to endure. Cleveland’s industries may have roared during the 1920s, but they nearly collapsed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. At times during the Depression as much as 30% of the workforce was unemployed. While the Depression was the ultimate working person’s crisis, it also served, under the guidance of the Roosevelt administration, to provide the impetus to legitimize the worker’s right to unionize. When jobs returned, they often came with wage levels and benefits that labor had long sought. Only with the advent of World War II did full employment return. Highly unionized industrial jobs survived after the war, supported in large part by the fact that major global competitors, both prior (Germany) and potential (Japan), had been decimated by the conflict. However, by the late 1960s Cleveland, along with other industrial centers in the Great Lakes region, began to lose jobs to more competitive locales both within and outside the United States.

Certainly, the civic and business leadership of the 1920s could not have clearly foreseen the future—otherwise they would have sold short in 1929 and reinvested heavily in the late 1930s. But, there were signs all around them that presaged enormous and challenging changes in the years to come [—changes whose general nature could be divined to some extent, even if the specific debacle of the market crash and the subsequent temporary renaissance of Cleveland as an industrial city could not have been predicted. And by and large, the leadership remained oblivious to these signs].

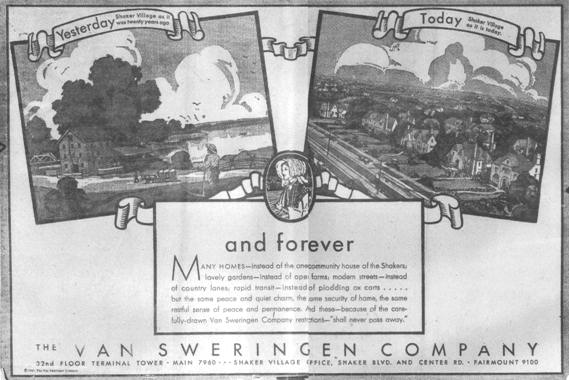

That impending change was exemplified in the careers of Mantis J. and Oris P. Van Sweringen, real estate dealers who not only created Shaker Heights as a landmark in American suburban development, but also reshaped the core of the downtown area with the construction of the Terminal Tower complex. Essentially, the Van Sweringens were the successors to the Connecticut Land Company. They bought, developed and sold vast tracts of land outside of the central city. They were not alone: real estate was a booming local industry in the early twentieth century, both because the city’s growing population needed new home sites and also because many people were by this time striving to escape the central city. While such individuals’ motivations can never be clearly defined, they rested upon the desire for something better—better in the sense of greener, in the sense of larger, and in the sense of being away from the unpleasant, which might be categorized as smoke, pollution, and people not like them.

What was even more important about these new suburban developments is that they were planned to be separate from Cleveland. The city’s growth during the later nineteenth century came about in substantial part through the annexation of previously independent outlying communities. Those communities wanted to link to the city and its services. Yet in the first two decades of the twentieth century four major communities—East Cleveland, Lakewood, Cleveland Heights, and Shaker Heights—were established as separate corporate entities along Cleveland’s borders. In the decades that followed, particularly after World War II, the creation of discrete suburban communities would increase substantially. The process was and remains a rejection of the central city based, one might argue, on its political culture, its polluted landscape, and the nature of its population.

Transportation, the key component enabling suburban expansion, also presaged a different future for Cleveland. For nearly a century, Cleveland’s industrial hegemony was virtually locked in by its access to water transport and major rail lines. However, by the late 1920s automotive and truck transport had grown in importance. By the 1930s new roads and highways were being built, some with the aid of federal WPA dollars. After the war the network would expand enormously with the construction of the interstate system. Now freer to relocate, many industries left for more modern facilities in the distant suburbs or, often, for the lower wage rates and non-unionized labor available southern states. Eventually, some would decamp to places outside the boundaries of the United States.

The city’s leadership during the 1920s also witnessed the beginning of a major demographic change in the city, one that would challenge its attempts to promote harmony and cooperation among its many ethnic communities. Ironically, the process of building harmony within a diverse population was apparently well under way during the 1920s, symbolized most tangibly by the establishment of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens. While many American cities promoted a strong 100% American agenda during World War I and the decade thereafter, Cleveland stood apart by creating public programs that allowed various communities to retain and celebrate aspects of their heritage in a public manner. They included folk festivals near the Cleveland Museum of Art, the accumulation of a strong folk arts collection by that agency, and the series of Cultural Gardens stretching along what was then called Liberty Row as a memorial to Clevelanders who died in the war. All were initiatives sanctioned by either the local government or those who oversaw the community’s cultural agenda.

The real irony of this was that the movement to Cleveland of Europeans, whose cultures were the focus of these programs, began to wane at the outbreak of World War I and then was largely ended by restrictive immigration legislation in the early 1920s. Their place as laborers was taken up in substantial part by African American migrants. Cleveland’s black population grew as a consequence of the Great Migration from the South. It stood at 2,062 in 1900, increased to 8,447 a decade later, and by 1920 had risen to 34,451. Within the next decade it would more than double, to 71,899. African Americans had always been present in the region. Indeed, during the antebellum period, the city’s New England roots made it a bastion of antislavery sentiment and a stop on the Underground Railroad. At that point Cleveland was a place where a free African American was treated with reasonable equality. Within four decades after the Civil War had ended, this tolerance was being eroded by growing racial bias. When large numbers of blacks arrived in Cleveland during and after World War I, they found themselves segregated into the Cedar Central area, with their economic opportunities limited by prejudice. Absent European migration and given the increasing need for workers during the Second World War, the black population again expanded during what is known as the Second Great Migration, growing to 147,850 in 1950, and rising to 250,818 at the beginning of the 1960s. The racial division in the city, combined with a declining economy, led to the Hough riots of 1966 and the Glenville shootout of 1968, the /most intense episodes of communitarian violence in the city’s history. At that time, the Cultural Gardens, adjacent to both neighborhoods, lacked a site that specifically honored African-American heritage.

Racial tension, out-migration to the suburbs, and the loss of industry made the 1960s and 1970s one of the most complex periods in the city’s history. Cleveland’s population peaked at 914,808 in 1950. Twenty years later it was 573,822. During this same period, the population of Cuyahoga County, excluding Cleveland, rose from 474,724 to 924,578. Manufacturing employment reached its highest point in 1969, and then declined by one third over the following twenty-one years. The impact of out-migration and loss of industry on tax revenues was considerable. In 1978 the city defaulted on $14,000,000 in loans to six local banks.

In many ways the decades of the 1960s and 1970s were as significant an historical watershed for the community as the decades centered on the Civil War. Both marked transitions, each of which was problematic. While in retrospect one can see the switch to an industrial economy as the beginning of a local golden age, it needs to be remembered that wrenching change occurred because of this shift. We easily forget about farmers and skilled independent producers such as shoemakers, blacksmiths, and seamstresses whose livelihoods were damaged or destroyed by industrial production. Indeed, we celebrate the image-building consequences—governmental reform, private-public partnership, philanthropy, modern social services, and a strong cultural infrastructure—which were catalyzed by disruptive industrialization.

In many ways, but not all, these community assets have assisted the city and region in moving forward in their search for a new economic basis and social stability Tangible entities, such as community centers and foundations—most particularly the Cleveland and Gund Foundations—have played significant roles in areas such as neighborhood redevelopment, the fostering of intercultural relations, and the provision of feasibility studies or seed funding for entrepreneurs and businesses. Importantly, some of the not-for-profit entities created by the wealth of the industrial period have emerged as major players in the new economy. Modern health care, perhaps the key “industry” in twenty-first-century Cleveland, has its roots in voluntary organizations such as the Ladies Aid Society of Old Stone Church, and the benevolence of industrialist-philanthropists such as Samuel Mather: the former laid the groundwork and the latter then helped secure the funds for the growth and modernization of what is now University Hospitals of Cleveland. Cultural institutions such as the orchestra, art museum, and natural history museum help to make University Circle a tourist destination at a time when tourism and the service industries that support it are seen as critical economic contributors to post-industrial Cleveland. Additionally, non-industrial entities such as corporate law firms and banks, which were created to serve the industrial expansion, continue as active and important components of the service economy.

It can also be argued that the intangible aspects of the city’s image can catalyze actions that benefit the community in times of crisis. Despite the intense local racial divide in the twentieth century, a tradition of liberality seems to have continued. It led to the establishment of fair employment practices legislation in the late 1940s; played a significant role in the election of Carl B. Stokes as mayor—the first African American mayor of a major US city—in 1967, and underpinned the creation of organizations such as the Lomond and Ludlow associations, which worked to insure desegregation and a balanced population mix in two neighborhoods in the once exclusive suburb of Shaker Heights. Altruism seems almost ingrained in the community’s psyche. Some would claim it derives from the tradition of stewardship brought to the region by the early Protestant settlers from New England. Today, thanks to that tradition, fortified by similar impulses in the Catholic, Jewish, and non-Judeo Christian communities, and abetted by a variety of federal laws, Cleveland and northeastern Ohio are home to dozens of philanthropic foundations, both private and corporate.

Yet, the issue posited at the beginning of this chapter still looms for Cleveland and northeastern Ohio. Cities are economic entities, and those attributes of civilization that come to make up their public image or persona are the consequences of vibrant economies. The wealth created in Cleveland and northeastern Ohio during the region’s industrial apogee was enormous, so much so that it has continued to support culture, charity, and education up to the present. The question remains as to how long the residue of that wealth can continue to support communal needs and cultural amenities, and also whether prosperity generated by the evolving medical and service economy can make up for any loss and secondarily, even increase the legacy generated by the industrial period. There is reason to be sanguine here, for if one carefully reads the names on new buildings in educational, cultural, and medical complexes, one sees a shift to surnames that do not reflect the heritage, both ethnic and entrepreneurial, of nineteenth-century industrialists. Rather, they belong to individuals whose migration stories are more recent and whose fortunes were created, in part, in real estate, building, and finance.

If there is one matter that tends to lessen this sanguinity, it is the matter of definition—definition of the community in terms of legal boundaries and demographic composition. The essential economic substructure of the community tells us that “Cleveland” is more than the area within the city’s borders. Interestingly, the broader economic community today roughly fills the outline of what Connecticut held as its Western Reserve. Similarly, the amenities of Cleveland, the city, are enjoyed by an audience that lives throughout the region— sports teams belong to residents not only of Cleveland but all of northeastern Ohio as do its orchestra, art museum, and other cultural treasures. Major health care providers centered in the city operate branches throughout the region. Despite this regional unity based on economics and shared amenities, there is still a struggle to develop a coordinated approach to governance, education, and policy. The movement toward regional government, which began in the 1930s, is an unfinished item from the early post-progressive agenda. There have been successful efforts toward regionalism in the park system, water and sewage, and public transit which have extended such services beyond the city’s boundaries. However, the economic, ethnic and racial divisions that endure within Cleveland and its surrounding communities complicate any move to a system of governance that would have pleased those who made Cleveland an efficient city and a national model some one hundred years ago.

The Public Square of Cleveland has, true to its New England origins, endured as a communal area for over two centuries. It has been in turn a village commons, the “Monumental Square” of a growing mercantile center, and the busy hub of the fifth largest city in the nation. Yet, it has remained geographically intact through major, and for many individuals, cataclysmic changes in the community’s economy. It is surrounded by buildings that seem to show that the city and the community can deal with vast demographic change. First Presbyterian Church stands near the Metzenbaum Court House, named after a Jewish US Senator; near the Square are the Lausche State office building, named after a Slovenian mayor, governor, and senator, and just beyond it, the Stokes Federal Courthouse, named after another mayor, the grandson of a slave. These buildings have a potent symbolism, one that is reflected even more strongly in the diversity of the crowds who come to the Square on July 4th to hear the annual open-air concert by world-famous Cleveland Orchestra. These symbols auger for what needs to come next to insure that the community survives. It is not so much the move to a new economic base: that is already largely underway. It is the need to move beyond the parochial and to construct a functional regional community— a twenty-first century Western Reserve which identifies with its economic cohesiveness and fully accepts, rather than simply celebrates its global heritage.

John J. Grabowski holds a joint position as the Krieger-Mueller Historian and Vice President for Collections at the Western Reserve Historical Society and the Krieger-Mueller Associate Professor of Applied History at Case Western Reserve University. He has been with the Society in various positions in its library and museum since 1969. In addition to teaching at CWRU he serves as the editor of The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History and The Dictionary of Cleveland Biography, both of which are available on-line on the World Wide Web (http://ech.cwru.edu). He has also taught at Cleveland State University, Kent State University, and Cuyahoga Community College. During the 1996-1997 and 2004-2005 academic years he served as a senior Fulbright lecturer at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey. Dr. Grabowski received his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in history from Case Western Reserve University. He is a member of Phi Beta Kappa.