The complete doctoral dissertation written by Robert H. Bremner, The Ohio State University in 1943

Be patient, the document will take a few minutes to download.

The download is here (approx 45mg)

www.teachingcleveland.org

The complete doctoral dissertation written by Robert H. Bremner, The Ohio State University in 1943

Be patient, the document will take a few minutes to download.

The download is here (approx 45mg)

if above link does not work, try this

Terrific essay written about Newton D. Baker after his death by Frederick P. Keppel for Foreign Affairs Magazine, April 1938. Strongly recommended.

By Frederick P. Keppel FROM OUR APRIL 1938 ISSUE

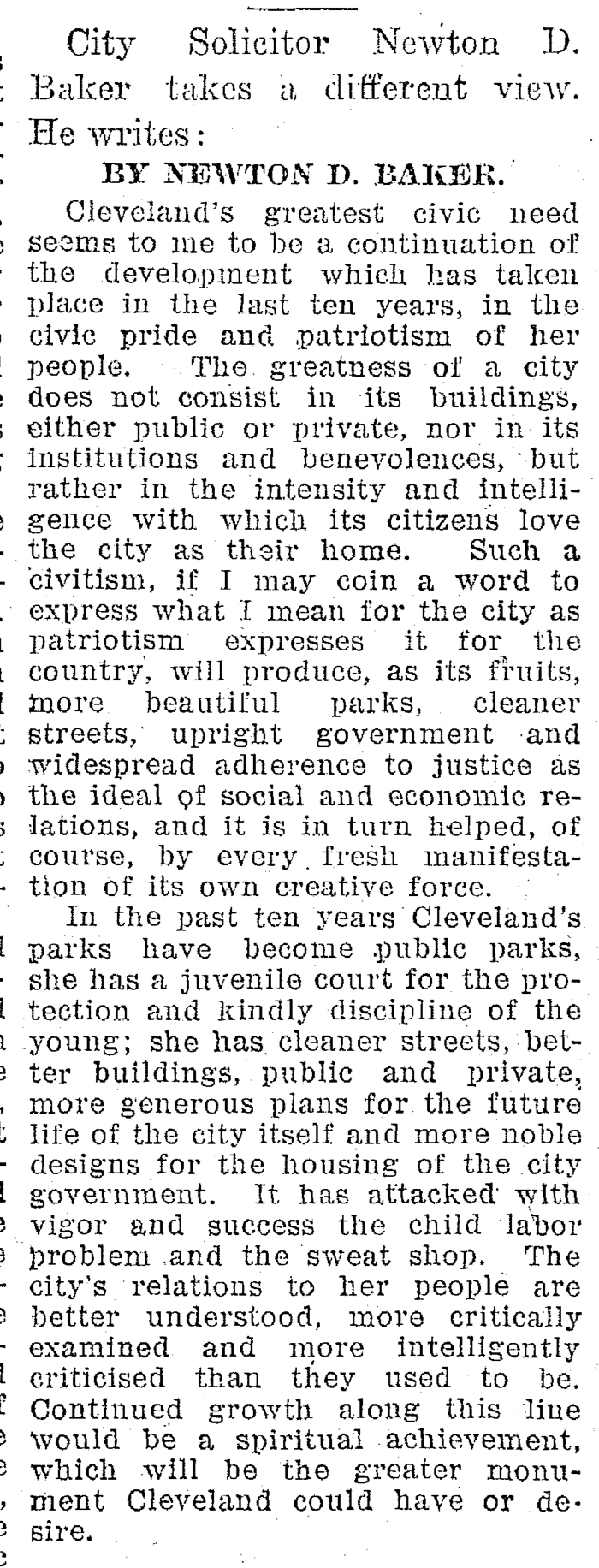

NEWTON BAKER, though a seasoned public servant, was far from being what is called a national figure when he went to Washington as Secretary of War in March 1916; and on the Atlantic seaboard at least, the appointment definitely offended our folkways. Of course the new Secretary had to be a Democrat, but here was clearly the wrong kind of Democrat. He came from Cleveland, not a good sign in itself, where he had been the disciple and successor of Tom Johnson; he had found nothing better to tell the Washington reporters at his first interview than that he was fond of flowers; and he belonged to peace societies (so did his predecessor, Elihu Root, but that was different). Could Woodrow Wilson have done worse had he tried?

Few of us changed our minds about Baker within the first months of his service. Yet at the Armistice he stood without question in the front rank of our citizens; and in direct violation of the rule that in an ungrateful democracy service in a national emergency is to be quickly forgotten, the years remaining to him were ones of steadily growing reputation. His death on Christmas Day last drew forth unique expressions of admiration and affection from all sections, all parties, and all classes. And yet the man who had died was the same man who came to Washington in 1916, ripened by time and by great responsibilities it is true, but the same man. The change was in ourselves. My effort here is an attempt to trace the steps and to set forth the reasons for that change.

The story of his administration of the War Department has been told by Frederick Palmer in “Newton D. Baker: America at War,” and told with sympathy and understanding; we cannot reach our objective by briefly repeating that story, nor can we reach it by comparing Baker’s record with that of his predecessors in wartime, and for two reasons: first, the vastness of the undertaking in 1917-18 threw all previous experience out of scale; and second, our military organization had, since the Spanish War, been re-created “under Elihu Root’s counselling intelligence” — to use Baker’s own phrase. What I set out to do is much more personal in character, and the task has not proved to be an easy one. Natural gifts and long practice had indeed made Baker one of our outstanding public speakers, and a volume of wartime addresses collected by his friends in 1918, “Frontiers of Freedom,” [i]provides fruitful reading, as do the addresses which later found their way into print, including his greatest effort — the eloquent and deeply moving plea for the recognition of the League of Nations made at the Democratic Convention of 1924. It is true, also, that no adequate collection of American state papers could fail to include a few of his departmental writings (in general, these are to be found in Palmer’s book) and that there are other important writings of his — to which reference will be made later on. The entire printed record, however, tells us but little about the man himself, for the good reason that when he spoke in public or wrote for publication the very last thing in his thoughts was Newton Baker. With his genius for friendship, he was, as Raymond Fosdick has pointed out, one of the few remaining exponents of an almost lost art, that of letter writing, and it would have been much more to our present purpose if his voluminous and many-sided correspondence had been available.

It has really been by something like a process of elimination that I have been brought to seek the nature and degree of Baker’s influence and the steady growth of his renown, not in the printed record, but rather by gathering together the impressions he made upon all sorts and conditions of men in direct personal contact. Inevitably my thoughts went back to the early days of the war, when I saw him daily and nightly, and what has come to me after these twenty years is no steady stream of recollection, but rather a cavalcade of separate incidents, of figures singly or in groups crossing the stage of memory — each individual as he left the scene carrying away some impression of the man.

Let me try to reconstruct a typical day in his office in the late spring or summer of 1917. At 8.30 A.M. Herbert Putnam might arrive, and in five minutes the Secretary would understand both the wisdom and the practicability of libraries in the training camps of our citizen army, and of having the books later accompany the soldiers to France. Next, a Plattsburg enthusiast who had come to scold might find himself, much to his astonishment, remaining to listen and learn; or some fellow liberal would have to be disabused of the idea that the war was a heaven-sent experimental laboratory for some pet social theory. Fosdick would drop in to go over some point about camp facilities, or Tardieu about the available ports of debarkation in France, or General Bridges about temporary provision for our soldiers in England. Big business and transportation and labor would have their representatives, and members of Congress were always in the anteroom, insistent on prerogative in direct proportion, it seemed to us, to the unimportance or impropriety of their purpose. At noon Baker would come out to give at least a handshake and a smile, often an understanding word, to the scores of private visitors for whom it was physically impossible to arrange private appointments. Then home to luncheon with his wife and children, his one act of self-indulgence. Afterward, there might be a quiet hour with Dr. Welch of Johns Hopkins on what modern medical care might contribute to the health of the soldiers. On such occasions he was not to be interrupted, however loudly the heathen might rage in the anteroom. Meanwhile, throughout the day and in the evening the Chief of Staff and the Bureau Chiefs were of course demanding and receiving a full share of his time. In between he somehow managed to conduct an immense correspondence, the formal signing of the departmental mail sometimes taking the better part of an hour, and many of the letters and memoranda he must needs prepare himself being none too easy to compose. The sound of the Provost Marshal General’s crutches in the hall told us it was 10 P.M. We could almost set our watches by him, for Crowder (whose wounds, by the way, had been received not in battle but in falling from a Pullman berth) had promptly learned the value of a daily discussion on the problems of a nation-wide draft with this son of a Confederate soldier, who had been raised in a small town, whose student days had been passed in Baltimore and Lexington, and who for fourteen years had been a public officer in Cleveland.

As the long days succeeded one another there were occasional calls from President Wilson, who never announced his coming and never stayed long; and almost daily meetings with Secretary Daniels and other Cabinet officers. One day we would have a phalanx of college presidents, who saw their students melting away and who wanted their institutions taken over — or at least financed — as training camps. On another, a delegation from a city not necessary to name might come to challenge the authority of the War Department to mend their morals for them just because a divisional camp was to be established nearby. In this case the Secretary conceded that the point of law was well taken, and suggested the wholly unwelcome alternative of changing the location of the camp. On still another day our T.V.A. of today was, I remember, born in a discussion regarding the sources of power for a nitrogen fixation plant great enough to ensure an unlimited supply of explosives. Once the Secretary scandalized us by explaining in German the intricacies of the draft law to a delegation of Hutterian Brethren, an offshoot of the Mennonites. Another time former Secretary of State Elihu Root came to discuss the Mission to Russia. Officers ordered to France had to be slipped in secretly to say goodbye. I can recall taking the future Chief of Staff, General March, out on a balcony and in through a window of the Secretary’s private office. Then there were official receptions for generals and statesmen from overseas, conducted with the active and, to us juniors, not always welcome, advice and counsel of the State Department. The frequent meetings of the Council of National Defense also were held in Baker’s office and made cruel demands on his time, though they doubtless served their purpose. And, of course, there were many calls to take him outside of his office — Cabinet meetings, Congressional committees, visits to nearby training camps.

And this kind of thing went on all day and every day from eight-thirty in the morning until eleven at night (only two or three hours less on Sunday), but nothing that happened could ever ruffle the tranquillity of the Secretary. How the favorite disciple of the excitable Tom Johnson could maintain throughout the alarums and excursions of wartime Washington this calm imperturbability was beyond our comprehension.

During this period Baker made one hasty trip overseas. Though naturally different, his days there were just as strenuous as those in Washington. Our officers behind the lines were proud of the docks and warehouses and hospitals they were building, and those at the front wanted to show him the morale and appearance of their men. Their determination that the Secretary should see all with his own eyes meant long and arduous trips, between which must be found time for serious discussions. That these discussions were fruitful, we have the public evidence of General Harbord and Charles G. Dawes, Pershing’s right-hand citizen soldier; Sir Arthur Salter has told me that it was directly due to Baker’s quiet but effective presentation of the situation that the British Government diverted so large a proportion of their ships from highly profitable trade routes to transport our soldiers and supplies.

Slowly at first, and then with increasing rapidity, the picture at Washington changed. Into the service of the War Department itself, men of affairs, accustomed to making decisions rather than passing the buck, were being absorbed. Outside it, the direction of the various war boards and war administrations fell into competent hands. Other Federal departments, notably the Treasury, were strengthened by the acquisition of men of first-rate ability. As a result, the direct pressure of non-military matters upon the Secretary of War was correspondingly lightened, and he could concentrate his attention on the problems which came to him not via the public reception room but through the door connecting his office with that of the Chief of Staff.

Until the end of 1917, however, no clear distinction could be drawn in Baker’s daily work between his military and his civilian activities. He had, in fact, to stand between and, so far as possible, to reconcile two very different human attitudes. The military way of thinking and acting is based on long tradition; instinctively, it avoids lights and shades and doubts; while there might be private jealousies, the Army thought and acted essentially as a unit. The American people, on the other hand, were far from united in 1917. Many were definitely hostile to the whole enterprise, many more were at that time indifferent; certain elements were already outdoing Ludendorff himself in war spirit; very few had any conception of what war really meant. In the task of building up an Army the civilian attitude put much more emphasis than the military upon applications of new scientific knowledge, upon matters of comfort and health, physical and mental, and social and recreational services of all sorts. It recognized, as the Army did not at first, the repercussions upon civil life, that the War Department, for example, was becoming the country’s largest employer of civilian labor. It was the Secretary’s task to bring about a fusion of these two strains, and the degree of his success may be measured by the fact that the United States was able to build up a great Army, whose courage and endurance were beyond question, whose health record, despite the influenza epidemic, was extraordinary, and whose behavior was the best in the world’s history. Two years after the call which brought four million men to the colors, there were actually fewer soldiers in military prisons than there had been when that call was issued. It was, as well, an Army which it proved possible to reabsorb into civil life without undue confusion and difficulty.

Curiously enough, Baker the pacifist won the confidence of the Army officers before he enjoyed that of the public at large. Or perhaps this is not so strange after all. Few men in the Army or the Navy are militarists in the sense that our super-patriots deserve the title. It is no wonder that he and Tasker Bliss, scholar and philosopher as well as soldier, should achieve a prompt meeting of minds; but his success, though not so immediate, was equally complete with the more conventional type of professional soldier. Even before the outbreak of war the Bureau Chiefs with civilian responsibilities, men like McIntyre of the Insular Bureau and Black of the Engineers, had found him a Secretary after their own hearts, who had the brains and industry to understand the matter in hand, who in consultation with them would reach a decision, and having reached it would stay put. Of Crowder’s conversion I have already spoken, and we know that all these men passed the word along to their fellow officers in the combat branches who had not come into contact with the Secretary.

As to the civilian attitude, on the other hand, we had only to read the daily and weekly press (when we had the chance) to know that outside the Department there was widespread misunderstanding of the Secretary, and more than one center of implacable hostility. It was hard for us to judge whether the countless civilian visitors were exerting an influence in his favor, for, in general, after their visits they promptly left our sight. One very important type of civilian, however, remained under our observation. Baker was incredibly patient but quite firm with the members of Congress who wanted favors for constituents, and little by little it became recognized that though the Secretary’s quiet No might be disappointing, no one else would receive a different answer to the same question. In his relations with the two Committees on Military Affairs the picture is somewhat different. Here the Secretary, in his desire to defend his military associates from charges which he knew to be unfair, showed himself rather too skillful as a counsel for the defense to permit the establishment of an early entente cordiale. With the more thoughtful members, however, and notably with Senator Wadsworth and Representative Kahn, Republican leaders of Democratic committees though they were, a basis of mutual respect and confidence was established and maintained throughout the war.

The culminating event of this first period of Baker’s war administration was his account of his stewardship to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs on January 28, 1918 (twenty years ago, to the day, as this is being written). This was the occasion to which the anti-Bakerites had been looking forward in order to “get” the Secretary and force his resignation. Baker, be it said, recognized the good faith and patriotic motives of the great majority of his critics (there were exceptions to be sure, but these didn’t count in his mind). He himself was far from satisfied with the progress that had been made in certain essential services and, if it were made evident that a change in direction would be in the public interest, he was just as ready to step aside as when he had offered to resign his place in the Cabinet upon Wilson’s reelection. But his testimony revealed such an amazing grasp of the problem as a whole — and in all its parts — so clear a picture of pending difficulties and of the steps being taken to surmount them, that the more thoughtful of his critics saw at once that in going farther for a Secretary of War the country might well do much worse; and though criticism was to continue, this day marked the turning point in the civilian attitude.

At the time, as I have said, we knew only dimly and in part what kind of picture all these people who saw the Secretary of War were taking away with them — soldiers, legislators, scientists, professional and business folk of all sorts — how they described him to their wives that night. But in retrospect, and in the light of Baker’s later reputation, which must of necessity have been built up in large part on just this basis, I can, I think, present a pretty fair composite sketch.

His visitors arrived expecting to see a functionary, with all that this implies. They found a man short in stature, fragile in build, who never raised his voice in protest or command, never clenched his fist, never lost his temper. They found a man as completely selfless as it is possible for a human being to be, who instantly and instinctively assumed the other man’s sincerity of purpose. Needless to say, this led to occasional disappointments and disillusions, but these were rare and they never embittered his reception of the next visitor. A common meeting ground for discussion was promptly established, and a well-furnished mind, clarity of understanding, and an amazing power of exposition were placed at their service, and at their service as of right and not by favor. But there was, I am sure, something more than these recognizable and more or less measurable qualities to be reckoned with — something intangible, something rich and rare in the man’s personality which made his friendship a major event in one’s experience. When in the spring of 1917 Theodore Roosevelt referred publicly to Baker as “exquisitely unfitted to be Secretary of War,” he builded better than he knew in the selection of his adverb, if not of the word which followed it; “exquisite” is the mot juste to characterize that delicate combination of personal qualities which had so much to do with Baker’s power.

If I had to choose the one quality in his make-up which exercised the most potent influence upon soldier and civilian alike, it would be his courage, an undramatic but imaginative courage, broad enough to cover both a gallant recklessness and a philosophic fortitude. His effective support of the Selective Draft demanded that sort of courage, particularly from so recent a convert to its necessity. To set the pattern of American participation upon so vast and costly a scale took both imagination and courage. And certainly, to break all American tradition by giving the General in the field a free hand and protecting him from criticism meant both courage and fortitude. It was Pershing who kept Leonard Wood on this side of the Atlantic; it was Baker who silently received the resulting storm of protest.

The day-by-day administration of his office gave him many other opportunities to show his mettle. In the general confusion, Congress had adjourned in March 1917 without enacting necessary Army Appropriation Bills; yet for weeks the Secretary by “wholesale, high-handed and magnificent violation of law” (to quote Ralph Hayes) placed contracts for scores of millions of dollars without a vestige of legal authority. Later on, in the selection of officers to fill key positions in the United States, he bided his time, perhaps he overbided it; but when in his judgment the day had come to act, he acted with cool courage. To pass over the entire Quartermaster Corps with its special training, and to choose as Chief of Procurement a retired Engineer officer took courage, even though the man selected was the builder of the Panama Canal, George Goethals. Today it is no secret that in selecting Peyton March as Chief of Staff at a crucial moment the Secretary followed his personal judgment rather than that of his military advisers. March was recognized as a man of the first ability, but to say that he was not popular with his fellow officers is to put it conservatively, and it took something more than courage to make the appointment, for the Secretary quite accurately foresaw that thenceforth many things would be done not as he himself would do them, but in a very different fashion, and that his would be the task of binding the wounds to be inflicted right and left by a relentless Chief of Staff. There can be no question, however, that this selection, and the free hand he thereafter gave to March to reach his objectives in his own way, did much to hasten the termination of the war.

Let me give one final example of Baker’s fortitude. After the Armistice the President asked him to be a member of the Peace Commission, an invitation he would have rejoiced to accept, not only because he had something to contribute, but because he sensed, I feel sure, that his presence might have another value, for the President was always at his best with Baker. His clear mind realized, however, that his own war job was only half done, that two million men had to be looked after until they could be shipped back from France, and that these and two million others must be reabsorbed into civil life; there was no shade of hesitation or regret when once more he quietly said No.

It would be no kindness to Baker’s memory to maintain that there was no ground for criticism of his administration, and it would indeed ill become a member of his personal staff to do so, for in the earlier days we ourselves were critical enough. We loved him for his faults, but we were sure that the faults themselves were grievous: outrageous overwork; too much tobacco; hours spent in suffering fools, if not gladly, at least with reprehensible patience; over-consideration of the feelings of the unimportant; and, worst of all, a habit of watching and waiting and listening when the situation in our own judgment demanded a prompt and brilliant decision. It was only later on that we could see that his sense of timing was much better than either his friends or foes could realize. It was only in retrospect, too, that we could give him credit for the double gift, so rare in an executive, of leaving some things alone and of seeing that other things didn’t happen.

After the war there came four occasions for looking backward; each in its own way throws light on Baker’s reputation. The change in national administration in 1921 brought in its train the inevitable official inquiries which sought to find evidence of wrongdoing and particularly of corruption in the conduct of a war which had cost more than $1,000,000 an hour to conduct. The net result of the 37 charges considered by the War Transactions Section of the Department of Justice was two convictions and two pleas of guilty, all in relatively minor cases. As Mark Sullivan put it, “All the charges and all the slanders against Baker’s management of the war collapsed or evaporated or were disinfected by time and truth.” The next two occasions were more or less accidental, but none the less significant. The first was the appearance in the American supplement of the “Encyclopædia Britannica” in 1922, of a seemingly malicious article on Baker. He himself refused to get excited about the matter. In fact, he wrote to a friend: “I am not so concerned as I should be, I fear, about the verdict of history . . . it seems to me unworthy to worry about myself, when so many thousands participated in the World War unselfishly and heroically who will find no place at all in the records which we make up and call history.” His friends, however, rallied to his defense, and the result was a flood of published letters from men who knew at first hand of the Secretary and his work. A meeting of the American Legion in Cleveland in 1930 revealed his popularity with enlisted men as well as officers.

Finally in the preëlection year of 1931 there was the customary scanning of the horizon for presidential timber. Newton Baker was obviously in the line of vision, and there was much discussion of his qualifications. In these discussions it became clear that to some degree the sides had shifted: certain of his former liberal and radical supporters found the middle-aged lawyer with a large corporation practice wanting in qualities they had admired in Tom Johnson’s City Solicitor, and said so in the condescending style which reformers permit themselves. On the other hand, journals and writers that had been openly anti-Baker in 1917 came out strongly in his favor. Baker himself took no part in the proceedings. He hadn’t the slightest intention of going gunning for the nomination. Whether he would have accepted it had it been offered, I do not know. As a good party man, he might have done so, but on the other hand he had already had intimation that his heart had been seriously affected by the strain put upon it fifteen years earlier, and this might well have settled the question in his mind.

In writing for this quarterly, certainly, the question of Baker’s interest in foreign affairs must not be overlooked. In his university days he had been a student of history, and thereafter, no one knows how, he had kept up his reading. War itself is perforce an international enterprise, and to keep our forces in France together and under our own flag took constant and difficult diplomatic negotiations with our Allies. It is the general testimony that the leaders from other lands whom he met in Washington and elsewhere both understood and admired him, and I have a theory that one of the reasons, a reason of which he himself was quite unconscious, was that like Dwight Morrow of his own generation, like Irving and Hawthorne in the last century, Baker has his place in the line headed by Franklin and Jefferson, the line of those who stand as living demonstrations that one can be as authentically and refreshingly American as Uncle Sam himself, while at the same time conforming to the standards of quiet good manners and sharing la culture générale of the Old World.

But it must be added that in his relation to foreign affairs, as in other matters, Baker declines to be subdivided, even in retrospect. His internationalism is only one reflection, though an important one, of an underlying and indivisible faith in our common human nature and faith in the power of ideas. He was no more interested — and no less — in the problem of a coerced minority in the Danubian region than of the corresponding troubles of a Negro group in an American city. He would work with equal ardor toward a joint understanding between China and Japan, or to bring Protestants, Catholics and Jews together here at home.

To understand the years remaining to Newton Baker after he left Washington in 1921 one essential factor must be kept in mind. It would be easy to picture him as a professor in any one of half a dozen fields of scholarship, or as a diplomat, or editor, or executive; but his choice of the law as his life-work, made as a very young man, was as authentic a “call” as any man has ever had to the ministry. He had scarcely started on its practice, however, when he was drawn into the public service, in which he was to remain with hardly a break for a score of years. His return to Cleveland was above all a return to his first love. There was no lack of reciprocal affection on the part of the law, and as a result all his other activities were conditioned upon having to fight for the time he could devote to them.

That his mind was constantly at work upon questions of peace and war there is abundant evidence. Take for example the following passage from his Memorial Address at Woodrow Wilson’s tomb in 1932:

The conference at Paris demonstrated that the sense of victory does not create a favorable atmosphere for the construction of just and enduring peace. The portions of the Treaty of Versailles that were dictated by the spirit of victory are largely the parts of that treaty which still obstruct peace. Nations, like men, have emotions, are sensitive to hurts to their pride, and in moments of passion submerge their better selves.

The only sort of peace which can endure must come from a recognition of virtues as springs of national action as well as guides for individual behavior. The future peace of the world cannot be secured by processes which attain diplomatic successes and inflict diplomatic defeats, which inflame nations with a sense of aggrandizement or humiliate them with a sense of wounded pride.

And somehow he found time to do not a little serious writing. In “War and the Modern World,”[ii] the memorial lecture for 1935, he paid the boys of Milton Academy the compliment of giving them his best. “Why We Went to War,” first published in this review,[iii] was really a tour de force, of which he himself was naively proud. The outward and visible sign of this self-challenge to do a thoroughly scholarly job despite an overwhelming pressure of other tasks was a second desk moved into his office, and piled high with volumes and reports. How and when he found the time to digest the material and write the treatise remains a mystery.

I shall not enumerate his services on national commissions or on private boards, educational, philanthropic and professional, except the Wickersham Commission of 1929, and those on Unemployment Relief in 1930, and on the Army Air Corps in 1934. They drew heavily upon energies which by this time it was all too evident he should have been conserving.

No man in his senses would add all these things to the engrossing demands of an active law practice; but then I am not maintaining the thesis that he had any sense — about himself. He didn’t, and there was nothing to do about it. Those of us who, following a British precedent, had organized a Society for the Preservation of Newton Baker, got no coöperation whatever from the subject of our solicitude, and we decided before long that the pain of refusal might really be worse for him than the additional strain of acceptance. From time to time during the last few years he did give up some voluntary service, and made a great virtue of it, but he never failed to replace this by at least two others.

Before the reader lays down this article, I should like him to know that it is not what I myself had meant it to be — namely, an appraisal of a public service, sympathetic naturally, but dispassionate. It has turned rather into a tribute of personal affection. All I can say in extenuation is that the very same thing would have happened had the editor of FOREIGN AFFAIRS selected for the task any other of Baker’s associates.

[i] New York: Doran, 1918.

[ii] Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935.

[iii] FOREIGN AFFAIRS, v. 15, n. 1. Later published as a book by the Council on Foreign Relations.

Charles Willard State from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

STAGE, CHARLES WILLARD (26 Nov. 1868-17 May 1946) was a lawyer active in civic affairs and politics who became Cleveland’s first utilities director under the Home Rule charter.

Born in Painesville to Stephen and Sarah (Knight) S., Stage graduated from Painesville High School (1888). He received his A.B. from Western Reserve University (1892), the A.M. in 1893, and graduated in the first class of W.R.U.’s Law School (1895). Stage was captain of W.R.U.’s first football team, and was a National League umpire. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1895 and entered into private practice in Cleveland.

Stage served in the Ohio House of Representative, 1902-1903, and was Cuyahoga County Solicitor from 1903-1908. He was Secretary for the Municipal Traction Co., 1906-1908, and Secretary of the City Sinking Fund Committee, 1910-1912. Under Mayor NEWTON D. BAKER†, Stage was Public Safety Director, 1912-1914, and the City’s first Utilities Director, 1914-1916.

From 1916-1922 Stage was general counsel for the Van Sweringens. When Stage retired in 1938 he was vice president, director and general counsel for the Cleveland Union Terminal Co. and had been secretary and a director of the Cleveland Interurban Road Co., Cleveland Traction Terminals Co., Cleveland Terminal Co., Terminal Buildings Co., Terminal Hotels Co., Traction Stores Co. and Van Ess Co.

On 29 Aug. 1903 Stage married Dr. Miriam Gertrude Kerruish who died in the 1929 CLEVELAND CLINIC DISASTER. They had four children: Charles Jr., William, Miriam and Edward. Stage, an Episcopalian, was cremated.

Chapter V from Ohio’s Constitutions: An Historical Perspective by Barbara Terzian. Published by Ohio University Press

V. THE 1912 CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

Having rejected a proposed new constitution in 1874, Ohioans voted against holding a convention at all when the issue came up in 1891. By 1909, the agitation for social and political reform associated with Progressivism had reached such a peak that the general assembly submitted a referendum on holding a constitutional convention to the voters a year earlier than required. The Ohio State Board of Commerce (OSBC), hoping to reform taxation, was a major supporter of a convention. Other reform groups—organized labor, woman suffragists, prohibitionists, and political reformers—wanted a convention to achieve their own goals.148

For a decade, Progressives, led by Tom Johnson, the mayor of Cleveland, had been trying to open the political system. Johnson and other Progressives, such as Cincinnati clergyman Herbert Bigelow, were strong supporters of governmental reforms such as the initiative and referendum and municipal home rule. For years, Bigelow’s Direct Legislation League had been trying to persuade the legislature to put constitutional amendments effecting such reforms on the ballot. Frustrated by their failure, they decided to generate public support for a new constitutional convention. They viewed a constitutional convention as a means to incorporate their reforms into Ohio’s fundamental law, beyond the power of political party bosses to repeal or subvert.149

For many business people, the first priority was reform of the tax system. The Ohio constitution required a uniform system of taxation whereby all property, regardless of its nature, was taxed at the same rate.150

Modern economists and tax experts decried such an old-fashioned and inefficient system. The OSBC

had tried to pass amendments changing the tax system via referenda in 1903 and 1908.

Although garnering a majority of the votes cast on the specific issue, both times the amendments failed to

receive the absolute majority of all votes cast in the general election that was required to amend the constitution.151

Willing to negotiate with reform-oriented business people, organized labor formed an important element in the Progressive coalition pressing for constitutional reform. Having secured pro-labor legislation from the state legislature, they had been frustrated by court interpretations restricting its application or ruling it unconstitutional altogether. They wanted to establish clear constitutional authority for labor legislation and to restrict the courts’ power to inhibit it.

Allied with other Progressive reformers, Ohio women’s rights activists wanted to assure the passage of a woman suffrage amendment. The Ohio Woman Suffrage Association (OWSA), reorganized in 1885, had operated continuously ever since. By 1910 it had very strong ties with the national women’s rights organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Harriet Taylor Upton, the leader of the state association, was also NAWSA’s treasurer and located its headquarters in the Warren County courthouse from 1903 to 1910.152 OWSA coordinated activities for major

suffrage campaigns, althousome other women’s organizations, such as the Woman’s Taxpayers League

and the College Equal Suffrage League, remained independent of it.153

Prohibitionists also linked their reform to Progressive notions of using the state to promote social well-being. Because most observers believed women to be more inclined toward prohibition than men, that particular reform was linked, at least in people’s minds, to the woman-suffrage movement. The leading state and national organization advocating prohibition was the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), founded by Ohioans in the 1880s. The ASL had been so successful in passing local-option laws that sixty-three of Ohio’s eighty-eight counties prohibited the sale of alcohol as of mid-1909. The alcohol industry had tried to counter the ASL with its own public relations campaign aimed at convincing people that regulated saloons rather than prohibition were the solution to alcohol-related problems. The Ohio Brewers Association developed a program of driving saloons connected with gambling and prostitution out of business. As part of the campaign, the association had supported legislation that defined the appropriate “character” of a person owning a saloon. By 1911, its campaign seemed to be yielding success; eighteen counties had reverted to “wet” status. The constitutional convention would provide Ohio’s liquor interests with an opportunity to build upon their success. The “drys,” in contrast, hoped to promote statewide prohibition.154

The proponents of the convention were helped significantly when the legislature decided to permit political parties to place the issue on the party ticket, so that a straight party vote meant a vote for the convention. With so many different reform groups supporting a convention and with both parties endorsing it, the proposal passed handily in the referendum 693,263 to 67,718, far surpassing the required majority of 466,132.155

Attention then turned to the election of delegates, scheduled to take place along with the municipal elections in the fall of 1911. Districting for representation at the convention would mirror the elections for the lower house of the general assembly. The election would be nonpartisan, although candidates could formally declare whether they supported submitting the liquor-license question to the voters.156

Political reformers formed the Ohio Progressive Constitutional League to advocate on behalf of candidates who would support the initiative, referendum, recall, and municipal home rule. In Cincinnati, representatives from businesses, clubs, trade associations, and trade unions joined to organize a slate of reform candidates. In Columbus, the Franklin County Progressive League sponsored a slate composed of representatives of farmers, business, and labor. In Cleveland, organized labor played a major role, throwing its support to the Cuyahoga branch of the Progressive Constitutional League rather than the business-oriented Municipal Association. In the less urban areas, some Granger-labor alliances formed; in other areas, local Progressive Constitutional leagues led the effort to elect pro-reform candidates.157

The Ohio Woman Suffrage Association voted to petition the convention to submit a woman suffrage proposition

separately from the rest of the new

constitution. It formed a campaign committee, opened campaign headquarters in Toledo, conducted field work,

and tried to encourage the election of sympathetic delegates.158

With such an array of Progressive forces enlisted in the campaign to elect delegates, the resulting convention had a distinctively Progressive character. There were 119 delegates: fifty-nine from rural areas, thirty-two from towns, and twenty- eight from urban areas. Sixty-two of the delegates were affiliated with the Democratic Party, fifty-two were Republicans, three were Independents, and two were Socialists. According to historian Lloyd Sponholtz, the typical delegate was a white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, college-educated professional from a small town. Once again, law and farming were the most common occupations among delegates, with a smaller number of laborers, bankers, and teachers. Most delegates could be identified as Republicans or Democrats, but, in a rebuke to political “bossism,” fewer than a third had previously held office.159 The Ohio Woman Suffrage

Association estimated that fifty-six of the 119 elected delegates supported submitting a woman- suffrage

amendment to the electorate.160

Progressive leader Herbert Bigelow was elected president of the convention on the eleventh ballot, receiving more support from Democrats than from Republicans, an indication that the former were more sympathetic to reform than the latter. The convention created twenty-five committees to which proposals and petitions were sent for consideration. The delegates adopted rules similar to those of the Ohio House of Representatives, except that debate occurred on the second rather than the third reading of a proposal and that the author of any proposal could force it to the floor if it languished in committee for more than two weeks. Those committees deemed most important received twenty-one members, each representing a congressional district. The delegates worked in committees on Mondays and Fridays; the full convention met during the rest of the week.161 Early in the

proceedings, the delegates decided to amend the Constitution of 1851 rather than to write a completely

new one—perhaps with the fiasco of 1873-1874 in mind.162

As one of the leading advocates of the initiative and referendum, Bigelow naturally created a committee that was strongly sympathetic to it. Robert Crosser, who had submitted a home rule bill in the legislature in 1911, chaired the committee that had charge of it. Bigelow also caucused with sixty Progressive delegates to assure a favorable response once a proposal came to the convention floor. This process produced a recommendation for what the sponsoring committee called direct and indirect initiatives for legislation and constitutional amendments, each with different technical requirements. An indirect initiative was a proposal that first went to the legislature for action; a direct initiative went straight to the voters. The committee proposal made it more difficult to initiate directly a law or an amendment than to initiate them indirectly. A petition for direct initiation of legislation had to contain a number of signatures of electors equaling eight percent of the votes cast for the office of governor in the preceding election. Direct initiation of a constitutional amendment required a number of signatures equaling twelve per cent of the votes cast in the preceding gubernatorial election. An indirect initiative for legislation or a constitutional amendment required only half as many signatures. In all cases, the signatures had to come from at least one half of the counties in the state. The committee also proposed a referendum process by which voters could challenge a law passed by the general assembly and have the electorate vote whether to approve or reject the law. Those petitions required a number of signatures equaling six percent of the votes cast in the preceding gubernatorial election.163

The debate in convention centered on the number of signatures required to initiate the process and on whether to eliminate direct initiatives and to permit only the indirect method. The debates manifested a concern that the initiative would be used to pass taxation measures. The final proposal permitted direct initiation of constitutional amendments only, and required a number of signatures equal to ten per cent of the votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election to place the amendment on the ballot.164

Indirect initiation of laws would require a number of signatures equaling only three percent of the number of

votes cast in the previous gubernatorial

election. If the general assembly rejected the proposal, amended it, or failed toact on it within four months,

its proponents could force a vote by the

electorate by filing a supplementary petition with a number of signatures equaling an additional three percent of

the votes cast at the previous

gubernatorial election.165 Electors could also force a referendum on an ordinary bill initiated and passed by the

general assembly by obtaining a

number of signatures equaling six percent of the votes cast in the previous election.166 All petitions had to

include signatures from at least one-half

of Ohio’s counties.167 The provision explicitly prohibited using the initiative process to secure either a single

tax or tax classification.168

Sponholtz’s roll-call analysis indicates that opposition to the initiative and referendum came from rural and small-town Republicans. Democrats uniformly supported the initiative and referendum, with the greatest support coming from urban Democrats. Unable to prevent the proposal of an amendment to institute the initiative and referendum, conservatives still achieved a number of their goals by restricting the initiative process to the indirect method for legislation and by securing the concession that it could not be used to institute the single-tax idea.169

Conservatives even more vigorously opposed the recall process, whereby voters could terminate an elected official’s term prior to its expiration. Some argued that the terms of office were short enough to make recall unnecessary. Others worried that it could threaten the independence of the judiciary unless judicial officers were excluded from its provisions. Although an advocate of the recall was able to persuade the committee to endorse and report the measure to the convention, the delegates tabled the matter indefinitely. Instead, they proposed a fairly weak amendment to the constitution that authorized the legislature to pass laws to remove any officer guilty of moral turpitude or other offenses. Hostility to the recall was evenly spread across the political parties. More Democrats than Republicans supported the proposal; even so, only a minority of Democrats supported the stronger version. Even urban Democrats—the strongest supporters of the initiative and referendum—split on the issue.170

Urban home rule also proved divisive. The 1851 Constitution required the legislature to provide for the organization of cities and the incorporation of villages. Another part of the constitution required that all laws be uniform.171 The supreme court had sustained legislation that had classified cities

according to population and then treated them differently on that basis. This approach resulted in a range of

types of city organization even for cities

with similar populations. For example, Cleveland had a strong mayor, while Cincinnati had a figurehead mayor

with a powerful city council and board

of administration. In a suit instigated by traditional political leaders to clip the wings of Progressive mayors—

especially Cleveland’s Tom Johnson—

the Ohio Supreme Court in 1902 had invalidated all city charters for violating the constitutional requirement of

uniformity of laws. The court then had

delayed execution of its order to give the boss-dominated legislature time to pass a new municipal code.

Progressives, who predominated in some

cities, especially Cleveland, now pushed hard for home rule to reverse their earlier defeat.172

The “liquor question” figured into the debates. “Drys” did not want home rule to be used by cities to overturn state laws permitting subdivisions to ban the sale of alcoholic beverages. They were able to pass a proviso that no municipal laws could conflict with the general laws of the state. Both Republicans and Democrats generally supported home rule; it was primarily the rural delegates who expressed concern over its effect on local option.173

In the end, the constitutional convention passed a proposal that allowed local governments to choose among three alternatives: (1) to operate under the general laws of the state; (2) to amend a current charter; or (3) to call a charter commission to change or revise a charter. The amendment also provided that a municipality could own its own public utilities, a proposition that passed over the strenuous opposition of the public utility companies. The state legislature retained some control over localities through the operation of general laws and through some financial oversight. The convention delegates further reformed the political system by giving the governor a veto and establishing rules to govern the appointments to the civil service.174

Reformers and labor leaders had criticized the state courts for overturning labor legislation and maintaining common-law doctrines that advantaged employers at the expense of workers. The main criticism of the judiciary from lawyers and judges, on the other hand, was that the circuit court system was not working. When the circuit court heard appeals from lower courts, the losing party received a trial de novo there. Critics opposed this “two trial, one review” system. Lawyers and judges also criticized the requirement that each circuit court sit in every county seat in its district twice a year. The largest circuit included sixteen counties, forcing its judges to spend a lot of time on the road, and some other circuits were not much better. Two delegates led the judicial reform efforts in the convention: Judge Hiram Peck, who chaired the Judiciary and Bill of Rights Committee, and former Judge William Worthington, who also served on it. Peck’s proposal became the majority report; Worthington’s became the minority report.175

Both Peck and Worthington agreed that there should be a “one trial, one review;” that the jurisdiction of circuit courts should be limited to appellate review; and that the jurisdiction of the supreme court should be limited to constitutional cases, cases of conflict among the circuits, and cases the court deemed to be of “great public interest.”176 But Peck and Worthington also disagreed on significant matters. Peck proposed that the supreme

court remain at six justices with a three-to-three vote affirming lower court rulings. Responding to criticism of the

court’s anti- Progressive activism,

Peck’s proposal required a unanimous supreme court vote to reverse a lower court decision or to declare a law

unconstitutional.

Worthington’s conservative alternative proposed expanding the court to seven judges by the addition of a chief justice, a position that previously had simply rotated among the six judges. Worthington’s proposal eschewed the obstacles that Peck’s put in the way of judicial review and gave the court direct jurisdiction over appeals of state administrative regulations. He included this last provision at the particular behest of the Railroad Commission, which had complained that its regulations routinely became embroiled in litigation. The Ohio State Bar Association endorsed Worthington’s more conservative proposal over Peck’s.177

The debates concentrated on whether to require a minimum number of justices to declare a law unconstitutional and on the “one trial, one review” system, with the most time spent on the latter. The delegates compromised, but nonetheless gave labor and other Progressive groups a big victory. They proposed adding a chief justice and provided a complex rule for determining the constitutionality of legislation. If a circuit court sustained the constitutionality of a law, it would require the votes of all but one of the supreme court judges to reverse the decision and find the law unconstitutional. If the circuit court overturned a law, a simple majority of the supreme court judges could either reverse or sustain the decision. The supreme court would continue to have original jurisdiction in writs of prohibition, procedendo, and habeas corpus, and would be able to bring cases up on appeal through writs of certiorari.178

Under the adopted proposal, the circuit courts would provide appellate review of lower court decisions, with a trial de novo only in chancery cases. The circuit court’s decision was final except in constitutional questions, felonies, cases of original jurisdiction, and cases certified to the supreme court. A circuit court could reverse on the weight of the evidence only with a unanimous decision; on any other basis, a simple majority would suffice. Conflicting decisions among the circuits would be certified to the supreme court.179

Tax reformers, beaten down by the opposition of rural delegates to the most important elements of their program, were less successful in securing changes they wanted. Ohio’s 1851 Constitution required that real and personal property be taxed at the same rate. The OSBC urged the convention to propose an amendment permitting classifications of subjects of taxation and requiring uniform taxation only within the classifications, exempting federal and state bonds from taxation entirely. The OSBC succeeded in having its proposal reported from committee, supported by urban delegates who were worried about revenues keeping up with urban growth. Rural delegates disagreed, and their minority report mandated a uniform rule of taxation, with public bonds included.180

The convention roundly defeated the majority report by a vote of ninety-seven to nineteen and adopted the minority report as the basis for discussion. Debate centered on the rural delegates’ desire to provide constitutional sanction for the existing law’s cap on taxation.181 Rural delegates also opposed giving the legislature the power to classify property for taxation at different rates. Urban delegates tried, but failed, to give the voters a choice between a uniform tax provision and one authorizing classification. The third area of debate centered on exempting municipal bonds. Municipal bonds had been taxed as personal property prior to 1905 when voters ratified a constitutional amendment exempting them. Rural delegates did not like the exemption and wanted the constitution to eliminate it.182

The delegates finally compromised to some extent. Taxation would be uniform, and state and municipal bonds would be subject to taxation. The legislature could choose either a uniform or graduated income tax. The proposed amendment permitted franchise and excise taxes; taxes on coal, gas, and other minerals; required a sinking fund to pay the principle and interest on any indebtedness; and forbade the state from incurring debts for internal improvements other than road construction. In an “attempt to salvage as much as possible by surrendering the principle of classification,” urban delegates persuaded the convention to drop the proposal for a constitutionally mandated limit on taxation. In its final form, the amendment “pleased no one.” The OSBC did not get classification; rural delegates did not get a tax limit; and urban delegates, still worried about revenue keeping up with growth, lamented the lack of municipal control over revenues.183

In addition to its success in restricting the supreme court’s power of judicial review, organized labor also obtained seven amendments embodying much of its constitutional reform program: a maximum eight-hour work day on public works; the abolition of prison contract labor; a “welfare of employees” amendment authorizing the legislature to pass laws regulating hours, wages, and safety and health conditions; damages for wrongful death; limits on contempt proceedings and injunctions; workers’ compensation; and mechanics’ liens. There was little resistance to any of the proposals except those abolishing prison contract labor and limiting court injunctions.184 Because domestic and farm labor were exempted, the “welfare of employees” amendment drew little opposition except from a few employer delegates.185 The final prison-labor proposal abolished the existing system but permitted prisoner-made products to be sold to the state and its political subdivisions, and encouraged convict road gangs.186

The proposal to limit court injunctions produced heated discussion. Organized labor particularly wanted an amendment that would bar courts from issuing injunctions in strike situations and also sought the right to a jury trial in the contempt proceedings that often followed when strike leaders violated the injunctions. The Committee on the Judiciary and Bill of Rights reported a proposal favorable to labor, but the delegates voted it down on the floor of the convention. Nonetheless, labor supporters were able to pass a proposal that an injunction could be issued only “to preserve physical property from injury or destruction.”187

Woman suffragists also had a good deal of success at the convention. Harriet Upton and other OWSA representatives successfully lobbied the president of the convention to appoint sympathetic members to the Suffrage Committee. When the convention met in Columbus in January 1912, suffrage organizers opened headquarters there.188 Suffragists registered as official convention lobbyists and worked to influence members of the Elective Franchise Committee, drafting a suffrage proposal for the committee’s consideration.189 The suffragists also testified, discussing the differences between men and women and insisting that men could not fairly represent women. Advocates argued that women were needed in politics to work for better roads and against impure food and high living costs.190

Other women organized to oppose the proposed amendment. They, too, testified before the Suffrage Committee and held a rally. The anti suffragist witnesses favored limiting suffrage to exclude working people and those of foreign birth. They argued that granting universal suffrage would permit undesirable women to vote. On February 14, 1912, the committee issued its report, rejecting the anti suffrage arguments and proposing an amendment to Ohio’s constitution that would remove the words “white male.” Newspapers nicknamed the committee report the “Con-Con’s valentine” to Ohio’s women.191

The male delegates speaking in favor of woman suffrage echoed the arguments the women had made in committee. They consistently argued that women were the equals of men and that the right to vote was a natural, inalienable right.192 Delegates who supported the initiative and referendum must, to be consistent, also support submission of the woman suffrage proposal.193 Some supporters urged support of woman suffrage to promote the chances of prohibition.194 Opponents argued vociferously that voting was not a right, but a privilege, which carried duties and responsibilities. It was unfair, they reasoned, to place this burden on women when a majority of them did not want it.195 Three times opponents of suffrage attempted to pass a proposal that would have required a preliminary referendum among Ohio women. Only if a majority of them voted in favor of suffrage would the amendment be presented to the male electorate for ratification. Each time the proponents of woman suffrage tabled the proposal.196

At the close of debate, the delegates voted in favor of the amendment by a margin of seventy-four to thirty-seven. They also voted seventy-six to thirty-four in favor of submitting the amendment to the electorate as a separate proposal.197 The convention subsequently decided to submit every proposed amendment as a separate item. The suffrage amendment appeared as the twenty-fourth of forty-two proposed amendments.198

After losing the vote on the amendment, opponents of woman suffrage turned to one last tactic that they hoped would defeat the amendment in the ratification election. They proposed an amendment that would remove only “white” rather than “white male” from the qualifications of electors, hoping to divert African American men from supporting the proposed universal-suffrage amendment by providing a male-only alternative.

Prohibitionists won support from a broad range of delegates, from Progressive reformers to rural conservatives. But the liquor industry had expended great energy in an effort to protect its interests, as well. Moreover, some urban Progressives and labor-oriented delegates worried that prohibition was aimed at their constituents. The liquor issue was couched in terms of licensing as opposed to no licensing because of the quirky language placed in Ohio’s constitution in 1851: “No license to traffic in intoxicating liquors shall be hereafter granted in this state; but the general assembly may, by law, provide against the evils resulting therefrom.”199

Thus, the liquor industry wanted to authorize licensing, while the advocates of prohibition opposed it. The Liquor Traffic Committee considered a number of proposals, with prohibition at one extreme and licensing, the details of which would be left to the general assembly, at the other. The committee issued both a majority report and a minority report. The majority report, sponsored by the known “wet,” Judge Edmund King of Sandusky, called for licensing without constitutionally imposed restrictions, while at the same time permitting local option laws. The minority report, advocated by the “drys,” contained strict restrictions on licensing.

After two weeks of intensive debate, the delegates rejected both versions. It became clear that the “wets” would be unable to get a licensing amendment without restrictions; the debate now centered on “no licensing,” which maintained the status quo, versus permitting licensing with severe constitutional restrictions. Delegates debated such issues as the number of saloons per capita, the number of infractions that would result in license revocation, how much home rule cities would have, and what “good character” limitations would be placed on licensees. Finally, the delegates decided to give the voters the choice of no license or restricted license. The restrictions included licensing no more than one saloon per five hundred inhabitants, the requirement that a licensee be a citizen of the United States of good moral character holding no other liquor interests, and that he reside in the county where the license was issued or the adjacent county.200

The delegates decided to have the ratification ballots list each amendment separately, to be voted on separately with a majority of the votes cast on each amendment sufficient for its passage. The delegates also voted that the president should appoint a committee to prepare a pamphlet for distribution to the public with a short explanation of each amendment. The entire pamphlet was also to be published in newspapers—at least two in each county and of opposite political party affiliation—for five weeks preceding the election.201

The convention had proposed forty-two amendments to the state constitution. The Progressive delegates, led by Bigelow’s New Constitution League of Ohio, campaigned for passage. The Democratic state convention endorsed all of the amendments and organized labor pushed for ratification as well. Most of the urban newspapers, with the exception of a few conservative publications in Columbus and Cincinnati, gave the amendments favorable coverage.202 Formal opposition came from the Ohio State Board of Commerce, which had failed to achieve its tax reform

and opposed the initiative and labor

amendments. The OSBC distributed tens of thousands of pamphlets attacking the convention’s work and

urging

voters, “[W]hen in doubt, vote no.”203

A handful of the amendments generated the most controversy, among them the initiative and referendum, liquor licensing, woman suffrage, and some of the labor amendments. The woman suffrage amendment was extensively debated, in part because of the suffragists’ efforts to generate support and in part because of vigorous opposition by the OSBC and the liquor interests. Local and national suffragists considered Ohio a crucial test for the extension of woman suffrage. Five other states had woman suffrage referenda scheduled after Ohio’s election, and suffragists hoped a positive outcome in Ohio would create momentum in those states. The OWSA established campaign centers in Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Toledo, Akron, Springfield, Canton, Dayton, Warren, and Youngstown. They organized 103 suffrage societies in 78 counties. The OSBC and the liquor interests, on the other hand, viewed women voters as potential temperance voters, warning Ohio’s male voters that a vote for woman suffrage was a vote to make Ohio dry.204

On September 3, 1912, Ohio’s male voters went to the polls. Urban voters favored almost all of the amendments. Voters in the northern part of the state, where Progressive mayors had been encouraging reform for years, supported the amendments more than those in the southern part of the state. Voters in seven rural counties voted against all of the amendments, voters in nine additional rural counties voted against all but the temperance amendment, and the urban vote made a difference in the passage of nineteen amendments that would have otherwise failed. Only eight of the forty-two amendments failed to pass, and the vote in each of those was relatively close.205

Herbert Bigelow was delighted with the outcome. The initiative and referendum, the passage of which he had been working for more than a decade, would now be a part of Ohio’s constitution. For the most part, organized labor was pleased. All of its amendments, with the exception of the anti-strike injunction provision, had passed. Women suffragists, on the other hand, were disappointed. Despite receiving the most favorable votes of any of the forty-two amendments, and the most cast ever in favor of woman suffrage in the nation, the woman suffrage amendment was defeated by a vote of 336,875 to 249,420.206

149 For a discussion of Progressive reform efforts in the decades preceding the 1912 convention, see WARNER, supra note 148, at 3-311.

150 OHIO CONST. of 1851, art. XII, § 2.

151 The 1903 vote was 326,622 in favor to 43,563 opposed, but the question needed 438,602 votes (more than one-half of the 877,203 votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election) in order to pass. The vote in 1908 was 339,747 in favor to 95,867 opposed, but the measure did not receive the 561,500 votes (more than one-half of the 1,123,198 votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election) required for passage. 2 GALBREATH, supra note 84, at 96.

152 FLORENCE ALLEN & MARY WELLES, THE OHIO WOMAN SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT: “A CERTAIN UNALIENABLE RIGHT”: WHAT OHIO WOMEN DID TO SECURE IT 39-40 (1952).

153 Kathryn Mary Smith, The 1912 Constitutional Campaign and Women’s Suffrage in Columbus, Ohio 11-12 (1980) (unpublished master’s thesis, Ohio State University).

154 The state local-option law required a revote every three years. In 1911 the first round of these revotes occurred. Eighteen of the twenty-seven counties holding the elections reverted to “wet” status. Lloyd Sponholtz, The Politics of Temperance in Ohio, 1880-1912, 85 OHIO HIST. 5, 9, 15-18 (1976).

155 GALBREATH, supra note 84, at 94.

156 Frey, supra note 148, at 3; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 22.

157 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 23-36.

158 Smith, supra note 153, at 27-29.

159 PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF OHIO 1-2 (1912) [hereinafter DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION]; Frey, supra note 148, at 3-4; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 6, 37-49.

160 Smith, supra note 153, at 28.

161 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 28-32; Frey, supra note 148, at

6-9, 13; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 51-55.

162 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 116, 650-52.

163 id. at 672-74, 681-83, 687, 733, 921, 951, 942-45. See Frey, supra note 148, at 35-47; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 143-51.

164 OHIO CONST. of 1851 (as amended), art. I, § 1a.

165 If the general assembly amended the original proposal, the proponents could force the original version onto the ballot by filing the supplementary petition. If both versions passed, the version receiving the highest affirmative vote became law. Id. art. II, § 1b.

166 Id. art. II, § 1c.

167Id. art. II, § 1g.

168 Id. art. II, § 1c. “A single tax” would tax the value of land to the exclusion of other property taxes. Some of the delegates at the convention, including Bigelow, were single taxers. They had been influenced by Henry George, a Nineteenth Century economist and philosopher, who started the single tax movement. In a best selling book, George theorized that taxing the full value of land would prevent a grossly unequal distribution of wealth and poverty. HENRY GEORGE, PROGRESS AND POVERTY (1879). Rural delegates at the convention strongly opposed the idea of a single tax system.

169 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 143-51.

170 Id. at 151-56.

171 OHIO CONST. of 1851, art. II, § 26.

172 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 157-60.

173 Id. at 156-69.

174 In 1903 Ohioans had given the governor a general veto power. The 1912 proposal gave him a line-item veto as well. Another proposed amendment limited the legislature, when called into special session by the governor, to consideration of only those issues specified in the governor’s call. WARNER, supra note 148, at 327. On the other hand, the 1912 convention reform reduced the margin needed to override a veto from two-thirds of the legislature to three-fifths of each house. 1 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 1496-97; Frey, supra note 148, at 59-60; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 177-79. Civil Service reform passed with very little opposition. WARNER, supra note 148, at 326; 2 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 1380, 1793.

175 Frey, supra note 148, at 58; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 190-92.

176 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 191.

177 Id. at 192-93; 1 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 1025-80.

178 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 1833-34; Frey, supra note 148, at 58-59; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 192-93.

179 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 193-94.

180 Frey, supra note 148, at 53; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 84, 93-95.

181 Frey, supra note 148, at 54; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 95-97.

182 Frey, supra note 148, at 54-56; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 96-97.

183 Frey, supra note 148, at 57, 72; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 99-101.

184 Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 127-40.

185 Id. at 132.

186 This may have been a concession on the part of organized labor to rural delegates. Id. at 131.

187 Frey, supra note 148, at 62; Sponholtz, supra note 148, at 133-38. There were labor supporters in all of the sectors, and urban delegates voted strongly as a bloc. Democrats supported labor fairly consistently. Republicans had problems with the injunction amendment, and there was a rural/urban split on it.

188 Smith, supra note 153, at 27-29.

189 Id. at 30.

190 [Columbus] CITIZEN, Feb. 9, 1912.

191Id., Feb. 14 & 15, 1912.

192 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 600, 603, 612.

193 id. at 602, 616, 623.

194 id. at 612, 618.

195 id. at 607.

196 id. at 626-29.

197 The third reading passed seventy-four to thirty-seven, and final passage came on May 31 with a vote of sixty-three to twenty-five.

198 The liquor interests had attempted to have the suffrage proposition set off with the liquor license provision and away from the other propositions, believing that this would aid in the defeat of the suffrage amendment, but the delegates at the Constitutional Convention supported the position advocated by the suffragists.

199 OHIO CONST. of 1851, art. XV, § 9; see also OHIO CONST. of 1851, sched., § 18.

200 This last requirement was intended to prevent a brewer or distiller from owning the saloon. Brewers owned an estimated seventy percent of the saloons in the United States. Frey, supra note 148, at 23-24; Sponholtz, supra note 154, at 20-24.

201 DEBATES OF THE 1912 CONVENTION, supra note 159, at 1923, 1981-84, 1998, 1999- 2011; WARNER, supra note 148, at 338.

202 WARNER, supra note 148, at 339. The Republican newspapers were the Columbus Dispatch and the Cincinnati Enquirer and Times-Star.

203 Id. at 340.

204 Smith, supra note 153, at 43, 53.

205 The amendments that failed to pass included elimination of the word “white,” the use of voting machines, the anti-strike injunction, woman suffrage and a separate amendment permitting women to hold certain offices, a ban on capital punishment, bonds for “good roads,” and restrictions on billboard advertising. WARNER, supra note 148, at 342.

206 Id. at 341.

From the Society of Baseball Research

Billy Stage

by Peter Morris

Who was the fastest man ever to step on a major league diamond? This question would surely provoke a heated debate among diehard baseball fans, with many names surfacing. It is a safe assumption that Billy Stage’s name would not come up, yet he is almost certainly the only man to hold world records in two sprint events at the time of his major league debut. Billy who? Don’t bother checking the baseball encyclopedias for his name because Billy Stage, only a few months after equaling the world record in the hundred-yard dash, became a National League umpire.

Charles Willard “Billy” Stage was born in Painesville, Ohio, on November 26, 1868, the second of three sons of Stephen K. Stage, a butcher, and the former Sarah Knight. His parents gave little thought to their boys attending college, but Billy developed a passion for learning and soon had his heart set on receiving a higher education. Even when his parents voiced active opposition to his plan, he insisted that he would work his way through college. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 2, 1894) That steadfast determination would become his distinguishing trait throughout his life.

So in 1888 Billy enrolled at Cleveland’s Western Reserve University, which had recently been renamed Adelbert College of Western Reserve. In addition to all of the time he devoted to his studies and to earning enough money to pay for tuition, he also found time to play varsity baseball and to serve as captain of the school’s first varsity football team.

It was at track and field, however, where he truly excelled. On May 28, 1890, Adelbert hosted a field day during which Billy Stage put on an astonishing performance. He was the winner in seven different events: the standing high and broad jumps, the fifty-yard backward dash, the hop, skip and jump, the half-mile run, and the 100- and 220-yard dashes. And in each of them except the novelty backward race, Stage posted the best performance turned in by an Ohio collegian that year. (Cleveland Leader, May 30, 1890)

What particularly captured attention was that he was clocked in ten-and-one-fifth (10.2) seconds in the 100-yard dash. The time raised both eyebrows and questions about its accuracy, since, as the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted, “If the time and distance were correct, it was a remarkable performance and only two-fifths of a second slower than the professional record.” (Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 29, 1890) But the Cleveland Leader defended its veracity, maintaining that the 10.2 second time “was that of the slow watch and there is no doubt of its correctness.” (Cleveland Leader, May 29, 1890)

His excited schoolmates began besieging the eastern track authorities of the Amateur Athletic Union (A.A.U.) with telegrams trying to enter him in that week’s intercollegiate championships. But their efforts were in vain. The response of the New York Times dripped with condescension: “Mr. Stage, who is well known to several men in this city, is a very promising amateur runner, having competed in a number of races in and near Cleveland and shown good times. It is doubtful, however, if his run Wednesday was timed accurately. He has run many times under eleven seconds with scarcely any training, and had only been training two weeks for Wednesday’s race. An Adelbert student will not be able to compete in the games to-morrow, that college not being a member of the Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes.” (New York Times, May 30, 1890) So Stage did not compete in the meet, at which the 100-yard dash was won in the same time that he had recorded at the Adelbert College field day. (Cleveland Leader, June 1, 1890)

When Billy Stage’s parents became convinced that their son intended to earn his degree with or without their support, they finally came around and began to help him out financially. He earned his undergraduate degree in 1892 and then enrolled in the university’s brand new law school. That October he competed at the A.A.U. championships and did well enough to be hailed as “the Cleveland phenomenon.” (Brooklyn Eagle, October 2, 1892)

By this time, it was clear that he outclassed his fellow Ohio collegians. When he arrived at the annual meet of the Ohio Intercollegiate Association for Athletics the following spring, the host Buchtel College (now the University of Akron) protested his participation and finally cancelled the meet on the grounds that he was “not an Adelbert man but a Western Reserve University man.” Most observers, however, saw this as a transparent excuse for the hosts’ realization that their representatives were no match for Stage. (Cleveland Leader, June 2, 1893)

To stave off any controversy, Stage joined the recently formed Cleveland Athletic Club, a decision that also enabled him to compete against the country’s top amateur runners. But it would prove far more a case of Stage putting the young club and the city of Cleveland on the track and field map than the other way around.

In September of 1893 he experienced a breakthrough that finally forced the Easterners to take notice. At the A.A.U.’s Central Association championships at Cleveland’s Athletic Field on September 2, he entered the hundred-yard dash against a strong field. The runners were tightly bunched for most of the race until a tall, curly-haired runner surged out of the pack. Billy Stage “broke the tape, or the Germantown-yarn to be more accurate” a full three yards ahead his nearest rival as “a large delegation of Adelbert students, who were present to see him run, could not repress their feelings and gave vent to a prodigious yell that aroused the jealousy of the announcer.” (Cleveland Leader, September 3, 1893)