Category: Charles E. Ruthenberg and Socialism in Cleveland

Socialist Municipal Administrations in the Progressive Era Midwest: A Comparative Case Study of Four Ohio Cities, 1911-1915 by Arthur E. DeMatteo

Paper delivered to the Ohio Academy of Historians in 2005

When Cleveland Saw Red by John Vacha

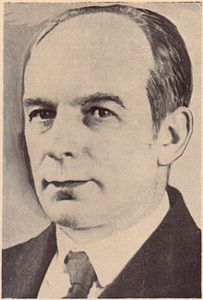

Charles Ruthenberg 1924 (wiki)

WHEN CLEVELAND SAW RED

By John Vacha

Along with the rest of the country, Clevelanders were shocked on the evening of September 6, 1901, to learn that President William McKinley had been shot in Buffalo, New York. What brought the news closer to home than elsewhere, however, was the knowledge soon to follow that the man who had fired the fatal bullet had been a resident of their own city. Leon Czolgosz was the son of Polish immigrants living in Cleveland’s Warsawa district on the southeast side.

A reporter from the Cleveland World tracked down the assassin’s father on Fleet Avenue. He had once run a neighborhood saloon, where a group of anarchists was said to have met in a hall above the barroom. “I think he is insane,” said Paul Czolgosz of his son. “I don’t think he is an anarchist. He is, I believe, a member of the Socialist Labor Party, but of no other organization.”

In fact, the younger Czolgosz had once been rebuffed in his attempt to join a local anarchist society and was a classic example of the loner in the history of American assassinations. Then as now, however, conspiracy-minded Americans were prone to associate foreigners and immigrants indiscriminately with such European political movements as Anarchism, Communism, and Socialism.

Even native-American politicians were not immune from such suspicions. Tom L. Johnson, Cleveland’s great reform mayor, may have been “the best Mayor of the best governed city in the United States” in the eyes of muckraker Lincoln Steffens, but businessman Mark Hanna saw Johnson as a “socialist-anarchist-nihilist.” Most of Johnson’s reforms happened to be as American as apple pie: paving and cleaning the streets, removing “Don’t Walk on the Grass” signs from city parks, building municipal bath houses, and instituting a city purchasing department to eliminate waste and corruption. The closest he carne to socialism was in his campaigns to establish municipal ownership of electric power and street railways. That was enough for conservatives like Hanna, whose antipathy couldn’t have been allayed by the sight of the mayor campaigning in a Winton automobile known as the “Red Devil.”

Tom Johnson was mayor of a city of 381,768 residents in 1900, one third of whom were foreign-born and three quarters of whom were either foreign-born or children of the same. Two thirds of the city’s working class were engaged in construction, manufacturing, and service trades, most of them was skilled or semi-skilled laborers. They lived in working-class neighborhoods dominated by up-and-down double or front-and-back-yard single houses. Many if not most still lacked indoor plumbing–hence the need for public baths. Working conditions were even more primitive than housing conditions, marked by low wages (15 to 25 cents an hour), long hours (10 to 12 per day), child labor, and sweatshop standards. Employers resisted workers’ efforts to organize for better conditions by the use of company spies, strikebreakers, and blacklists against workers involved in unionizing activities.

Two approaches were available for those workers who persisted in attempting to organize: the traditional craft unions of the American Federation of Labor or the class-oriented Socialist Labor Party. Labor unions sought to achieve their goals through collective bargaining with employers or government legislation, while Socialists sought broader reforms through the replacement of capitalism by a workers’ government that would take over and operate the major means of production.

While native-American workers tended to favor trade unions, and immigrants were more comfortable with socialist organizations from their European experience, there was a considerable overlap between the two approaches. Max Hayes, a native-born American printer, for example, was secretary of Cleveland’s Central Labor Union as well as a member of the Socialist Party of America. He co-founded and edited the official organ of the Central Labor Union, the Cleveland Citizen, and ran for Congress and Ohio Secretary of State on the Socialist ticket. He regarded unionism as his primary allegiance, however, and believed that socialists should work for reform through unions and the existing political system.

A major test for Cleveland’s union movement came with the garment workers’ strike of 1911. It started on June 6, when 5,000 Cleveland garment workers walked off the Job, only three months after 135 New York workers had died in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. Cleveland’s garment industry ranked fourth in the nation, and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union viewed it as a potential model for organization. Their demands included a fifty-hour work week with a half holiday on Saturdays and no more than two hours overtime a day, abolition of sweatshop conditions, and a raise in pay.

Garment manufacturers matched their striking employees in a display of solidarity. Refusing to negotiate with union representatives or agree to arbitration, the owners kept their businesses in operation by bringing in strikebreakers and sub-contracting with out-of-town plants. Strikers organized parades to promote their cause, including a march through the downtown business district by two female locals. The manufacturers countered by hiring agents to infiltrate the unions and incite members to violence. Told by one of these that their tactics were “too lady-like,” female strikers responded by assaulting scabs and police with their purses and fists, thereby turning public opinion against the strike. After five months, the strikers returned to work with none of their demands gained.

Such experiences undoubtedly prompted workers, especially those of recent European background, to consider socialistic solutions to the labor question. An estimated four out of five male workers, and two of five female employees, in Cleveland’s garment industry were foreign-born. When Charles Ruthenberg was ready to Join the Socialist Party in 1909, he found only eight English speaking locals in the city, as against eighteen of various nationalities, led by the Germans, Czechs, and Poles.

The son of German immigrants, Ruthenberg had begun his political odyssey as a supporter of Tom L. Johnson. Though still a believer in the free enterprise system, he was against special privilege and in favor of the mayor’s campaign for municipal ownership of the city’s street railways. Ruthenberg was not a laborer or tradesman but a white collar worker. Even before Johnson’s defeat in 1909, however, he was rapidly moving in the direction of socialism. Asked much later for the cause of his conversion, he replied, “Through the Cleveland Public Library.” When Eugene V. Debs, the most prominent socialist in America, spoke at Grays Armory in 1911, brochures listing the library’s holdings on socialism were distributed to those in attendance. Ruthenberg became recording secretary of Cleveland’s Socialist Party and within two years was running for mayor against Newton D. Baker and earning a respectable 8,145 votes.

It was a time fermenting with change, for socialists as well as progressives in general. Early in 1912, a state constitutional convention proposed no fewer than forty-one amendments to the Ohio constitution, last revamped in 1851. Voters approved thirty-three of them, including the great ballot reforms of initiative and referendum. Equally important for cities such as Cleveland was passage of a “home rule” amendment granting cities greater control over ways of addressing some of the unique problems of urban life. It had been drafted largely by Cleveland’s new mayor, Newton D. Baker, who promptly set about promoting the adoption of a new city charter.

Baker also played a prominent role in the Presidential election of 1912. At the Democratic National Convention he gave an impassioned speech from the floor which led to the overturning of the constitution’s unit rule, thus releasing nineteen of Ohio’s delegates to vote for the eventual nominee, Woodrow Wilson. A split in the Republican party between supporters of President William H. Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt virtually guaranteed Wilson’s election. So great was Baker’s dislike of Roosevelt that he expressed a preference for Eugene Debs, the Socialist candidate. In an unscientific exit poll of Cleveland theatergoers taken by the Cleveland Press, Debs actually outpolled Taft, finished third behind Wilson and Roosevelt. Wilson carried Ohio in the general election, but Debs picked up an impressive 89,930 votes in the state, a tenth of his national total of 900,000. Ruthenberg, the Socialist candidate for governor, was close behind with 87,709 votes. The party’s statewide appeal was much wider than its 3,500 dies-paying members, gaining Ohio a national reputation as the “Red State.”

Ethnic groups remained the core of the Socialist Party, especially in multi-cultural Cleveland. Many of their meetings took place in the old Germania Hall, rechristened Acme Hall when the original tenants, the Germania Turnverein, left in 1908 for newer quarters. On the west side, Socialist meetings were often called to order in a hall built by the Hungarian Workingmen’s Singing Club on Lorain Avenue. One Hungarian woman recalled passing the hat there for Socialist contributions following a Ruthenberg speech. Ruthenberg was often the featured English-speaker of the night at these gatherings, appearing at them often several nights a week. He would later observe that the best working-class daily newspapers in America all happened to be printed in foreign languages. One was the Americke Delnicke Listy (American Daily News), located in Cleveland’s Czech neighborhood on the southeast side. During the garment strike it had attempted to discourage strikebreakers by printing their names and addresses.

When war clouds gathered over Europe in 1914, Cleveland’s socialists turned May Day into an antiwar demonstration, marching through Public Square and rallying that evening in Acme Hall. War indeed broke out that August, and 3,000 socialists showed up in the rain for an antiwar protest in Wade Park. Though confined as yet to Europe, the First World War presented serious issues for American socialists, particularly those of foreign extraction. As socialists they were opposed to all wars as manifestations of capitalist rivalries. To the various Slavic and Magyar nationalities within the socialist movement, however, the war offered the promise of liberating their cultural homelands from German, Austrian, or Russian domination.

As events pushed America closer to participation, the war became more than an academic question f or American socialists and workers. Ruthenberg and the socialists campaigned against American entry right up to the eve of President Woodrow Wilson’s war message to Congress. They scheduled a stop-the-war meeting f or April 1, 1917, at Grays Armory, only to find the doors locked upon their arrival. Undampened, Ruthenberg led them in the rain to register their protest on Public Square.

For workers of all political persuasions, the war offered the benefit of high employment. Taking advantage of the wartime labor shortage, the garment workers again went on strike in 1918. The manufacturers this time agreed to submit the dispute to arbitration, but only at the urging of Secretary of War Newton Baker, former Mayor of Cleveland, who wanted to insure the supply of military uniforms. The workers not only won a substantial raise but secured union recognition in Cleveland’s men’s clothing industry.

America’s socialists found the government far less tolerant of their political activities. Foreign-born citizens, especially those from enemy countries, saw their loyalties under suspicion. An Americanization Board was established in Cleveland by the Mayor’s Advisory Committee to teach English to foreign-speaking aliens and to encourage them to become naturalized American citizens. Max Hayes and the moderate branch of the Socialist Party in general supported America’s participation in the war.

Charles Ruthenberg had become the recognized leader of the Socialist Party’s left wing. Even after America’s declaration of war against the Central Powers, he and other socialists continued to speak out against the war and the military conscription act. Given the choice between dropping his political activities or losing his position as office manager in one of Cleveland’s leading garment makers, Ruthenberg turned down a $5,000 raise and $10,000 stock offer to work full time for socialism. Alfred Wagenknecht, state secretary of the Socialist Party, was arrested at an antiwar meeting on Public Square, near the statue recently dedicated to Tom L. Johnson and free speech. (Years earlier, when the notorious anarchist Emma Goldman had come to town and dared Johnson to stop her from speaking, the mayor had invited her to have her say on Public Square.)

Ruthenberg and Wagenknecht were soon charged with obstructing the Conscription Act and sentenced to a year in the workhouse in Canton, Ohio. Even under sentence, Ruthenberg was on the ballot for mayor and received 27,000 votes, more than a quarter of the votes cast. Two Socialists were elected to the city council and another to the board of education in that election, though the board member was subsequently prosecuted under the Espionage Act and removed from office.

Eugene Debs came to Canton in 1918 to address the Socialist Party’s state convention. After visiting Ruthenberg in the workhouse, he went to the park across the street to deliver a fiery antiwar speech to a thousand supporters and a couple of note-taking government agents. Two weeks later, Debs was arrested as he arrived in Cleveland to speak at a socialist gathering at the Bohemian Gardens on Clark Avenue. He was tried for violating the Espionage Act in the U.S. District Court in downtown Cleveland and sentenced to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia. Following Ruthenberg’s example, he ran for President in 1920 and pulled in nearly a million votes from behind bars.

Despite such moral victories, socialism in the United States never recovered from the hysteria of World War I. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1918 in Russia brought hope to socialists everywhere, but fear and alarm to their enemies. Although fighting ended in November, 1918, wartime passions still burned fiercely in America, which had entered the conflict so belatedly. There were race riots in twenty-three American cities in 1919, fueled by the urban incursion of African Americans in search of wartime Jobs.

Cleveland had its own riots that year, but the targets were reds, not blacks. Some 30,000 socialists and their sympathizers gathered as usual on May 1 for the annual May Day observance. From various starting points they marched towards Public Square, where Ruthenberg was to deliver the oration of the day. Tens of thousands more lined the streets to watch, not all of them sympathetic. As the columns, Ruthenberg at the head of one, reached the more crowded downtown streets, onlookers began to attack the marchers, trying to snatch their red flags and break up their ranks. Among the attackers were army veterans, patriotic vigilantes, and, by some accounts, the police themselves. Two people were killed, scores sent to hospitals, and more than a hundred arrested, most of them marchers.

Officially, the May Day Riots were blamed on the socialists, who carried such “provocative” banners as “Workers of the World, Unite!” Even Max Hayes blamed the riots on incendiary statements by Ruthenberg. The city banned the red flag and talked of purchasing six tanks for riot control. Ruthenberg was arrested for “Assault with intent to kill,” a charge which was later dismissed.

Later accounts generally saw the marchers as the victims of mob action, spontaneous or even organized. “I saw a peaceable line of unarmed paraders attacked on an obviously preconcerted signal,” Cleveland Plain Dealer columnist Ted Robinson would write years later. “I saw men and women brutally beaten…. I saw the blood flow in sickening streams at the city’s busiest corner; I saw the victims arrested while the attackers went free; and I saw the fining and Jailing of these victims on the following day.”

By the end of that year, Ruthenberg had led the radical wing of socialists into the formation of the Communist Party of the United States. He became the party’s general secretary and spent his remaining years either organizing or fighting and serving prison sentences on such charges as advocating the violent overthrow of the government. At the age of 44, he died of peritonitis following a ruptured appendix in Chicago in 1926. His ashes were taken to Moscow, where he joined John Reed and Bill Haywood as the only Americans interred in the Kremlin.

It was largely the reaction of the Red Scare that prompted the United States to impose immigration quotas following World War I. Such legislation, and the illusory prosperity of the “Roaring Twenties,” checked the appeal of socialism in America. Not even the Great Depression could restore it to the strength it had demonstrated in Cleveland and other urban centers in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

To read more about Charles E. Ruthenberg and socialism in Cleveland, click here

Guilty? Of What? Speeches Before the Jury

Speeches given by Charles Ruthenberg, Alfred Wagenknecht and Charles Baker in front of the jury. They were accused of violating the Espionage Act in connection with a speech given at a rally on May 17, 1917.

Socialist Party of Ohio– War and Free Speech

Article from the Ohio Historical Society Journal

Charles E. Ruthenberg: The Development of an American Communist, 1909-1927

Article from the Ohio Historical Society Journal

Charles E. Ruthenberg from the Plain Dealer 1/21/96

Article about Charles E. Ruthenberg that ran in the Plain Dealer Sunday Magazine, January 21, 1996

CHARLES E. RUTHENBERG THE CLEVELANDER WHO FOUNDED THE AMERICAN COMMUNIST PARTY IS REMEMBERED BOTHAS AN INCREDIBLE VISIONARY AND A BITTER ANTAGONIST

He is setting the stage for a firebrand muckraker soon to arrive on a southbound train out of Toledo.

“Hear Charles E. Ruthenberg of Cleveland, the Socialist candidate for governor of Ohio, tonight at the corner of Main and Center streets!” shouts the workman, heading up Main with a megaphone and a hurricane lamp hooked on a long pole.

At the Fostoria train depot, a tall, blue-eyed, balding man with six toes on his left foot steps to the platform. He is traveling alone and no one, not even his comrade the town crier, is there to pick up his grip.

But welcoming fanfare and brass bands – the stuff of Democrats, Republicans and Bull Moosers – are not what Ruthenberg expects on this low-budget stump. “We have no corporations to donate thousands,” he tells the gaslight crowd. “Our fund must come from the working classes.”

Ruthenberg’s trip to the Seneca County town and his soapbox tirade against American capitalism that autumn night of 1912 are not even footnotes in Fostoria history. Not a Fostorian today has likely heard of Charles Ruthenberg. Even Clevelanders don’t know the name. And for years his family spoke of him in whispers.

“There was no way I would say I was related to this guy even though he was a hero,” says his granddaughter, Marcy Ruthenberg Pollack, who was raised in Bay Village and now lives in Flagstaff, Ariz.

Indeed, knowing that your grandfather founded the American Communist Party, served time in the infamous Sing Sing State Prison in New York, and had been dubbed “the most arrested man in America” is something you keep secret while growing up in Republican-heavy Bay Village.

Pollack remembers a mention of her grandfather in a documentary film about communism shown in Mr. Wells’ history class at Bay Village High School.

“I’m sitting there in my seat, trying to sink down, hoping they don’t think I’m related,” she recalls. “I’m thinking, `Are they going to tar and feather me or burn a cross on my front yard?’ My cheeks were so red.’

Though history has generally ignored Ruthenberg and at times treated him unkindly, the facts show he was a major player in Cleveland’s reform politics in the first decade of this century. In the 1920s, he was regarded as one of the most left-wing radicals in America.

Time magazine called him the “master Bolshevik” and “archenemy” of the State Department.

And the Philadelphia Bulletin said: “Ruthenberg is the chief official of a movement that admittedly is the chief instrument of Communist propaganda in this country.”

Inspired by the reform politics of Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson, Ruthenberg fought for municipal ownership of utilities and transit systems, helped organize unions for Cleveland teachers, garment workers and retail clerks, and in 1917 nearly won election as mayor. One newspaper printed a Ruthenberg victory in galley proofs. He polled more than 27,000 votes out of 100,000 cast in a three-way race.

But Lolly the Trolley tourists today can bet on not seeing a plaque or a landmark in memory of Cleveland’s famous radical. His legacy is just a few brittle newspaper clippings, yellowing in old, dusty files.

“He did not live to see the revolution, so his life’s work went for naught,” a Cleveland newspaper wrote when Ruthenberg died in 1927.

“He died alone at 44, shadowed by broken hopes,” Time magazine said.

Charles Emil Ruthenberg was born in 1882 to German-Lutheran parents in a house still standing on W. 85th St., near Lorain Ave.

In the days when children toiled in sweatshops, women and blacks had no vote and blue-collar men were sacrificed like kindling to the furnaces of industrial America, Ruthenberg’s job was agitation.

He began his political life on a soapbox at the corner of W. 25th St. and Clark Ave., and he ended it in ashes, sealed in a bronze urn inside the Kremlin Wall in Moscow.

He is one of three Americans – the others are journalist John Reed and labor leader Bill Haywood – buried in the Kremlin.

“Under the walls of the Kremlin the bed will be soft,” a Communist newspaper, the Daily Worker, wrote at Ruthenberg’s death. “Lenin and Jack Reed will be waiting to welcome you, Charlie.”

Ruthenberg’s parents, August and Wilhelmina, had come from Germany to Cleveland with their eight children in 1882, the same year their ninth and youngest child, Charles, was born.

In the old country, August was a cigar maker who, at 36 years old, became a widower with five children. He married Wilhelmina, a 28-year-old servant girl from Berlin who had a daughter, and the couple had three more children.

Wilhelmina was a dyed-in-the-wool Lutheran. August, a tough, black-bearded Cleveland dock worker and saloonkeeper, had no use for the church.

When Charles was 14, he went to work in a bookstore in the Old Arcade and took night classes in bookkeeping at a business school.

When he was 16, his father died and Charles took a job as a carpenter’s helper for a picture-frame company.

At 18, Ruthenberg, known to his friends as C.E. or C.E.R., became a bookkeeper and salesman for the Cleveland office of the New York publishing firm, Selmar Hess Co. There he met MacBain Walker, an atheist who had come from Albany, N.Y., with queer ideas like public ownership of utilities; worker-controlled factories; Utopian societies.

“I promptly began communicating these `poisonous’ doctrines to Charles, but the pupil was soon ahead of the teacher,’ Walker wrote in a 1944 letter to Oakley Johnson, Ruthenberg’s less-than-objective Communist biographer. “I would say that in two years, C.E.R. knew much more than I ever knew about such things.

“He … introduced me to Marx and scientific Socialism. C.E.R. continued to get more and more enthusiastic until he gave up business to devote his whole energies to the cause.”

For the next 17 years, Ruthenberg worked a variety of white-collar jobs while pushing Socialism throughout blue-collar Cleveland. In 1917, while employed as an executive for a garment manufacturer, the Printz-Biederman Co., he was told by his employer he would have to chose between his job and his politics.

The company said if he quit his radical avocation he would be given a $10,000 block in company stock, a pay raise to $5,000 a year and a chance to become vice president.

His boss, Mr. Fish, gave him 24 hours to decide. Ruthenberg, married with a 12-year-old child, had already made up his mind. “It isn’t dollars with me,” he said, opting for a stipend as a full-time organizer for the Socialist Party.

Ruthenberg had joined the party in January 1909, at age 26, and that summer he was preaching the political doctrine on soapboxes throughout the city. It was said he mixed metaphors and spoke with his eyes closed.

“He was ill at ease and did not seem to know what to do with his hands,” his longtime friend Ted Kretchmar wrote to Johnson in 1940. “However, he soon became adept in public speaking.”

Helen Winter, 87, of Detroit, formerly of Cleveland, recalls her mother taking her to hear Ruthenberg speak at Market Square, across from the West Side Market, when she was 8 years old.

The year was 1916 and Ruthenberg was railing against World War I, calling it “a war to secure the investments of the ruling class.”

“He was very good,” says Winter. “People were very attentive. There was no heckling. I think he stood on top of a car.”

Ruthenberg, however, is not remembered for goose-flesh oratory or inspiring quotations. His strength in the left-wing movement was his organizational skills and his whirlwind energy. He once organized 19 rallies protesting the espionage conviction of Socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs and spoke at five of them in one day.

He constantly wrote pamphlets and articles for local and national socialist magazines. And he was a perennial, albeit unsuccessful, Socialist candidate for public office – state treasurer, 1910; Cleveland mayor, 1911; Ohio governor, 1912; U.S. Senate, 1914; mayor, 1915; Congress, 1916; mayor, 1917; Congress, 1918; mayor, 1919.

He called for public ownership of ice plants, dairies, crematories and slaughterhouses, demanded more bathhouses in the city, and pushed for free lunches and textbooks in schools.

He fought for unemployment insurance, and helped establish a minimum wage in the city by collecting more than enough signatures to put the issue on the ballot, where it passed.

But the work kept him from his wife, Rose, and the couple’s only child, Daniel. When he wasn’t in a union hall, on a street corner or in jail, he was at Socialist headquarters on Prospect Ave., clacking away on a clunky old typewriter late at night, a cork-tipped Herbert Tareyton burning in an ashtray; a cup of black coffee going cold.

“CER was usually too busy to pay too much attention to me,” Daniel would later write as an adult. “He was away from home from 1918 to his death.”

If Ruthenberg was too busy to spend time with his child, it was often because he was in jail. He was tagged “the most arrested man in America.” From 1917 until his death there was only six months when he was not under indictment, in jail or under appeal on charges relating to overthrowing the government.

He was first collared in 1913 at E. 9th St. and Vincent Ave. during one of his soapbox soliloquies. Police hauled him to the station, but released him within hours without charge and the agitator went right back to the corner.

In June 1916, he stood at the foot of Tom L. Johnson’s statue on Public Square and condemned the sending of U.S. troops into Mexico. “There is no reason why any man should go down into the hell of war to fight for the dollars of the ruling class,” he told 1,000 people. The tirade attracted militiamen and a riot started.

“His speeches in halls and in Public Square generally were followed by trouble,” the Cleveland Press wrote after his death.

The United States entered World War I in the spring of 1917, prompting Ruthenberg to organize anti-war rallies throughout the city. He was banned from speaking at the City Club, the “citadel of free speech,” because of his stance against the war, according to Cleveland historian Thomas Campbell.

But Ruthenberg drew massive crowds at other forums: Moose Hall, Acme Hall, Grays Armory, East Technical High School, Public Square. He shouted, “War is murder,” and he urged citizens to avoid the draft.

That June, Ruthenberg and two colleagues, Alfred Wagenknecht (Helen Winter’s father) of Lakewood and Charles Baker of Hamilton, were indicted by a federal grand jury for obstructing the Conscription Act.

They were convicted in U.S. District Court in Cleveland and were sentenced to a year in the Canton Workhouse. Their appeals were unsuccessful and they spent 10 months behind bars.

In prison, Ruthenberg was tortured because he refused to work in a steamy basement laundry. He was strung up by his wrists with his toes just inches off the ground. When his lawyer, Morris Wolf, got word of the treatment, he went to Canton and demanded to see his client.

“C.E.R. almost had to be helped into the room,” Wolf told Ruthenberg’s biographer. “He slumped over and began crying. He was pale and in very bad shape.”

When Wolf threatened to go to the Cleveland Press, prison officials agreed to let Ruthenberg be hired out for farm work and later he was given clerical work in the prison office.

In June 1918, the Socialist Party of Ohio held a picnic in Nimisilla Park, across the street from the workhouse. Presidential candidate Debs was the speaker.

Before his speech, Debs visited Ruthenberg in jail. “They talked for a moment about the war and its cost in lives,” Wagenknecht wrote in 1940.

Debs then joined the picnic and from a rostrum he praised the courage of the three inmates and lashed out against the war. “When Wall Street says `war,’ the press says `war’ and the pulpit promptly follows with `amen,’ he told the crowd. The famous speech eventually resulted in Debs’ arrest and conviction in the same court that convicted the Cleveland trio. Although he spent Election Day in jail, the presidential candidate still polled nearly 1 million votes.

Ohio in those days was often called the “Red State” because of its socialist activity. But Ruthenberg’s shade of red was making the Socialist Party’s right-wingers uneasy.

As a top leader of the party’s left wing – which included non-English-speaking immigrants – Ruthenberg’s positions opposing the war and embracing the November 1917 Russian Revolution were splitting the ranks.

Right-wingers in the party were out to reform American capitalism to make it more palatable to socialist thought. But the Ruthenberg faction called for the complete elimination of capitalism and the establishment of a socialist state.

“He contributed much to the breakdown of the socialist movement in the United States,” New York Judge Jacob Panken, a socialist, wrote in 1958. “He may have been a dedicated man seeking the good of all mankind, but he was completely wrong in his ideas and tactics.”

The Plain Dealer wrote in 1927: “He flamed across the Cleveland firmament as a red radical of the deepest dye. … Ruthenberg, more than any other man in the United States, wrecked the Socialist Party that once polled nearly a million votes for Eugene V. Debs.”

In 1919, fresh out of the workhouse and still pumped up on radical dogma, Ruthenberg was back on the streets.

But by now, mainstream America was becoming less and less tolerant of Reds. Parades commemorating May Day – the international celebration of organized labor – were banned that year in many American cities. But in Cleveland, Ruthenberg led tens of thousands of immigrant workers bearing red flags through downtown streets, only to be ambushed by soldiers and vigilantes brandishing guns and clubs.

“I saw men and women brutally beaten, though they made no resistance,” Plain Dealer reporter Ted Robinson would write in an introduction to a novel about the Red scare of that time. “I saw the blood flow in sickening streams at the city’s busiest corner.”

Demonstrators Joseph Ivanyi, 38, of Woodhill Rd., and Samuel Pearlman, 18, of Kinsman Rd., were killed. More than 200 people, including 16 policemen, were injured. And 134, including Ruthenberg, were arrested. Of those arrested, only five were American-born. And most of the immigrants were deported.

Ruthenberg and Socialist leaders Tom Clifford and J.J. Fried were charged with assault to kill. The charges against the trio were eventually dropped, but the bloody May Day in Cleveland and riots in other major cities that spring day of 1919 signaled America’s angry mood toward a growing Socialism.

“The Red flag will never flutter in Cleveland again,” declared Safety Director A.B. Sprosty. “It is the insignia of disorder and blood. It is the symbol of anti-government.”

But Ruthenberg, who described the event as the culmination of his “will and purpose,” remained defiant. “The proletarian world revolution had begun,” he wrote four years later, recalling the “psychological attitude of 1919.”

“The workers were on the march. The Revolution would sweep on. In a few years … the workers of the United States would be marching step by step with the revolutionary workers of Europe.”

But peasant blouses and greatcoats were falling out of vogue in the United States as mainstream Americans were ready to flap and ragtime into the Roaring ’20s.

“The events of 1919 left us cynical rather than revolutionary,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in retrospect. “(M)aybe we had gone to war for J.P. Morgan’s loans after all. But because we were tired of Great Causes, there was no more than a short outbreak of moral indignation.”

In September 1919, left-wing Socialists meeting in Chicago broke away and formed the Communist Party, naming Ruthenberg the first general secretary.

But G-men, out to bust radical leaders and deport their foreign-born followers, were driving the Reds underground. “The reaction to Russia at that time destroyed the dissent movement,” says historian Campbell. “It killed a healthy criticism and the left never recovered.”

That year, Ruthenberg was arrested at least four times and he and seven others, including Irish socialist James Larkin, were indicted in New York on criminal anarchy for publishing the “Left Wing Manifesto.”

A four-week trial in New York in 1920 ended with Ruthenberg being sentenced to five to 10 years in Sing Sing State Prison. He spent a year and a half behind bars, taking a correspondence course in American history from Columbia University and writing daily love letters to his mistress, Rachel Ragozin, a Russian-born Jew raised in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Ragozin was a schoolteacher who joined the Socialist Party in 1914 because she was attracted to its position against World War I.

“War shocked me,” she told Ruthenberg’s biographer Johnson, although he never mentioned her in the biography.

Ruthenberg and Ragozin met at a party convention in Bridgman, Mich., on May 26, 1920, six months before he was sent to Sing Sing. During a break in the politics, they walked along the dunes near Lake Michigan.

“I was falling in love with him,” Johnson quoted her saying in unpublished, handwritten notes for his book. “His deep voice, his sweet smile, a nice soft look in his face as he looked down at me.”

By this time, Ruthenberg was living in Chicago where the Communist Party was headquartered, while Rose was in Cleveland raising Daniel alone. Though Rose kept a candle in the window for her husband, night trains coming through town carried his love letters to New York.

“Dear Rachel … When I finish this letter I will go to the cot in the corner and look down and see you resting there between the white sheets,” Ruthenberg wrote a month after they first met. “And I will wish with all my heart that you were really there, so that I might again kneel down beside you and put my arms around you and feel you(r) warm lips on mine and forget everything but that you love me and I love you. …”

Ruthenberg couldn’t keep his mind on his work while his lover was in New York. She seemed to become more important to him than the class struggle.

“Ten years ago a victory in a party struggle or to stand before a great audience and stir the people to wave after wave of applause … were things to be worth fighting for,” he wrote to Ragozin in June 1920. “But I no longer have illusions about these things. … The victory which I won in your weighing of me means more to me than any other victory.”

On a crisp, clear October day, a few weeks before Ruthenberg was convicted and sentenced, the couple took a train to upstate New York, where they walked in the countryside, collecting flowers and watching the sun set.

He told her: “They can’t shut me away from this, from all this beauty.”

But on Nov. 19, 1920, Ruthenberg was doused in a cold shower and caged in a Sing Sing cellblock. The notorious prison, built in 1825, was Ruthenberg’s home for 18 months.

“Even though there is the barrier of stone walls between us, that cannot rob me of the memories of the past,” he wrote to Ragozin on Nov. 25, 1920. “Those evenings when you taught me the names of the stars – I do not see the stars now – and my own Rocky River, which we visited together. All these are clear and bright in my mind and help to bring me peace and happiness, even here.”

Ragozin visited whenever she could, bringing him books and news of the movement.

“Sweetheart,” she wrote on Jan. 16, 1921. “In what way am I freer than you(?) The same walls that shut you in fetter me as effectively as if I were behind them.”

“Dear Rachel … It has been too long since you have been here. … Dreams, dreams, dreams and four stone walls and an iron door laugh back mockingly. … C.E. Ruthenberg #71624.”

Ruthenberg was locked up with Isaac E. Ferguson, a Communist leader from Chicago, who successfully worked on appeals and early releases for the two. They were freed in April 1922, and Ferguson, predicting Ruthenberg would be arrested again in six months, quit the cause.

He told Rachel: “There’ll be a lot of trouble in this struggle and a lot of dead. All the leaders will be sacrificed and I propose to live my life.”

He was too prophetic. Just four months out of Sing Sing, Ruthenberg and 16 other Communist leaders were arrested in woods near Bridgman, Mich., where they were meeting to plan the party’s upcoming convention in Chicago.

Ruthenberg was tried and convicted in state court on a charge of criminal syndicalism. The Michigan Supreme Court in 1924 upheld the conviction, and in January 1925 he spent two weeks in prison before U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis released him on a writ, pending a new trial.

The next month, Ruthenberg was back in national headlines: “15,000 Go Wild When Ruthenberg Asks Soviet Rule.

“Frenzy of Applause Greets His Plea in Madison Square Garden for Workers’ Regime in U.S.”

Ruthenberg told the massive New York crowd: “Prisons have only one effect on revolutionists. Prisons can only steel their will and increase their determination to strike blow after blow until the ugly capitalistic system which puts men in prisons is swept out of existence.”

He would never see the inside of a prison cell again. Two years later, the Michigan case still under appeal, his appendix burst and he was rushed to American Hospital of Chicago, where an emergency operation was performed on Feb. 27, 1927. He died of peritonitis three days later.

“RUTHENBERG IS DEAD,” shouted the bold headline across the top of the Daily Worker.

For two days, his body lay in state while honor guards in red shirts and black armbands kept vigil. Rose and Daniel arrived from Cleveland. He left only $50 in personal property.

A mass procession carried the dead Communist’s body to a crematorium and his ashes were sealed in an urn inscribed: “Our Leader, Comrade Ruthenberg.”

Sad comrades carried the urn to Carnegie Hall in New York for a memorial service, then on to Moscow, to a sepulcher in the Kremlin Wall. Red Army soldiers fired salutes, echoing across the great square.

“To you I bring from far America the ashes of my Comrade Ruthenberg, the fallen leader of our Communist Party,” J. Louis Engdahl said in his eulogy. “When American imperialism entered the world war, Ruthenberg stood before the masses in the open places of his native city of Cleveland, Ohio, and declared: `Not a penny to pay for the Wall Street War.’

“And American capitalism sent our Comrade Ruthenberg to prison because he dared speak, brave and courageous, for the working class of America.”

Back home, Ruthenberg memorials continued for weeks in union halls and left-wing gathering places, where the fallen comrade was eulogized as an American hero. But his place in history is subject to debate. Time magazine remembered him as “bitter, humorless, antagonizing more than he converted.”

And historian Theodore Draper wrote: “No great practical achievement and no significant theoretical contribution was linked with Ruthenberg’s name.”

But in fairness to Cleveland’s less-than-favorite son, maybe the best way to resolve the debate is to let Ruthenberg have the final say: “When you write my biography,” he wrote to Ragozin from prison, “just say I loved flowers.”

Rose died in 1967. Daniel died in 1989. It is uncertain what became of Ragozin.

“I don’t remember whether Rose knew of the other woman or not,” says Marcy Ruthenberg Pollack, the youngest of Daniel’s two daughters. She said Rose never discussed those turbulent days and rarely talked about her husband.

“We didn’t know my grandfather, but I think he had an impact on our family because we’re all pacifists,” she says today. “I know he was a pacifist. And I know that’s why he went to prison. To stand up for peace is not easy.”

May Day Riots of 1919

From the Encyclopedia of Cleveland

http://ech.cwru.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=MDR

|

The MAY DAY RIOTS, which occurred in Cleveland on 1 May (May Day) 1919, involved Socialists, trade-union members, police, and military troops. The Socialists and trade unionists were participants in a May Day parade to protest the recent jailing of Socialist leader Eugene Debs and to promote the mayoral candidacy of its organizer, CHAS. RUTHENBERG†. Its 32 labor and Socialist groups were divided into 4 units, each with a red flag and an American flag at its head; many marchers also wore red clothing or red badges. While marching to PUBLIC SQUARE one of the units was stopped on Superior Ave. by a group of Victory Loan Workers (see WORLD WAR I), who asked that their red flags be lowered, and at that point the rioting began. Before the day ended, the disorder had spread to Public Square and to the Socialist party headquarters on Prospect Ave., which was ransacked by a mob of 100 men. Two people were killed, 40 injured, and 116 arrested in the course of the violence, and mounted police, army trucks, and tanks were needed to restore order. Cleveland’s riots were the most violent of a series of similar disorders that took place throughout the U.S. Although it is uncertain who actually began the trouble, the actions of those involved were largely shaped by the anti-Bolshevik hysteria that permeated the country during the “Red Scare” of 1919. |

Charles Ruthenberg

From Wikipedia