Memorial to Jeffrey Miller, taken from approximately the same perspective as John Filo’s famous 1970 photograph as it appears today.

The Kent State shootings—also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre[2][3][4]—occurred atKent State University in the U.S. city of Kent, Ohio, and involved the shooting of unarmed college students by theOhio National Guard on Monday, May 4, 1970. The guardsmen fired 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.[5]

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced in a television address on April 30. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.[6][7]

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of four million students,[8] and the event further affected the public opinion—at an already socially contentious time—over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.[9]

Historical background[edit]

Richard Nixon had been elected President in 1968, promising to end the Vietnam War. In November 1969, the My Lai Massacre by American troops of between 347 and 504 civilians in a Vietnamese village was exposed, leading to increased public opposition in the United States to the war. In addition, the following month saw the first draft lottery instituted since World War II. The war had appeared to be winding down throughout 1969, so the new invasion of Cambodia angered those who believed it only exacerbated the conflict. Many young people, including college students and teachers, were concerned about being drafted to fight in a war that they strongly opposed. The expansion of that war into another country appeared to them to have increased that risk. Across the country, campuses erupted in protests in what Time called “a nation-wide student strike”, setting the stage for the events of early May 1970.

Timeline[edit]

Thursday, April 30[edit]

President Nixon announced to the nation that the “Cambodian Incursion” had been launched by United States combat forces.

Friday, May 1[edit]

At Kent State University a demonstration with about 500 students[10] was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 pm, another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to “bring the war home.” As a symbolic protest to Nixon’s decision to send troops, a group of students watched a graduate student burning a copy of the U.S. Constitution while another student burned his draft card.

Trouble exploded in town around midnight when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at cars and breaking downtown store fronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism and looting.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd had already lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared astate of emergency, called Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes‘ office to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.[7]

Saturday, May 2[edit]

City officials and downtown businesses received threats while rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances.[7] The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 pm, but the guard did not arrive into town that evening until around 10 pm. A large demonstration was already under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) building[11] was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended and no one was injured in the fire.[12] More than a thousand protesters surrounded the building and cheered its burning. Several Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called in because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it.[13][14][15] The National Guard made numerous arrests and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.[16]

Sunday, May 3[edit]

During press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk[17] and called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio. “We’ve seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police, and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we’re going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We’re not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They’re worse than thebrown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes”, Rhodes said. “They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we’re up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.”[18] Rhodes can be heard in the recording of his speech yelling and pounding his fists on the desk.[19][20]

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.[7]

During the day some students came into downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, which met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8:00 pm, another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 pm the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main Streets, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and President White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.[21]

Monday, May 4[edit]

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts an estimated 2,000 people gathered[22] on the university’s Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus’s iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.[23]

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice,[24] riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read them an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus Patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.[7]

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard’s line, to chants of “Pigs off campus!” The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on theirM1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of The Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading down toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about ten minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated off to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 ft (46 m) to 225 ft (69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others (perhaps 35 or 40) were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of the guardsmen knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. For a few moments, several guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About ten minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back down into the Commons.

At 12:24 pm,[1] according to eyewitnesses, a Sgt. Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the students with his .45 pistol.[25] A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their M1 Garand rifles at the students. In all, 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using a final total of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in the New York Times that “it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer.”[26] The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

Photo taken from the perspective of where the Ohio National Guard soldiers stood when they opened fire on the students

Bullet hole in a sculpture by Don Drummcaused by a .30 caliber round fired by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970

The Adjutant General of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which itself remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that “triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State.” The President’s Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that “the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.”[27]

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest, and the other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 225 feet (69 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Eyewitness accounts[edit]

Two men who were present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they’re not going to shoot, they can’t do that. If they are going to shoot, it’s going to be blank.[28]

Unidentified speaker 2:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit. He stumbled and fell, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

As this student fell behind the car, I saw another student go down, next to the curb, on the far side of the automobile, maybe 25 or 30 yards from where I was lying. It was maybe 25, 30, 35 seconds of sporadic firing.

The firing stopped. I lay there maybe 10 or 15 seconds. I got up, I saw four or five students lying around the lot. By this time, it was like mass hysteria. Students were crying, they were screaming for ambulances. I heard some girl screaming, “They didn’t have blank, they didn’t have blank,” no, they didn’t.[29]

Later that day[edit]

Immediately after the shootings, many angry students were ready to launch an all-out attack on the National Guard. Many faculty members, led by geology professor and faculty marshal Glenn Frank, pleaded with the students to leave the Commons and to not give in to violent escalation:

I don’t care whether you’ve never listened to anyone before in your lives. I am begging you right now. If you don’t disperse right now, they’re going to move in, and it can only be a slaughter. Would you please listen to me? Jesus Christ, I don’t want to be a part of this … ![30]

After 20 minutes of speaking, the students left the Commons, as ambulance personnel tended to the wounded, and the Guard left the area. Professor Frank’s son, also present that day, said, “He absolutely saved my life and hundreds of others”.[31]

Casualties[edit]

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

- Jeffrey Glenn Miller; age 20; 265 ft (81 m) shot through the mouth; killed instantly

- Allison B. Krause; age 19; 343 ft (105 m) fatal left chest wound; died later that day

- William Knox Schroeder; age 19; 382 ft (116 m) fatal chest wound; died almost an hour later in a hospital while undergoing surgery

- Sandra Lee Scheuer; age 20; 390 ft (120 m) fatal neck wound; died a few minutes later from loss of blood

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

- Joseph Lewis Jr.; 71 ft (22 m); hit twice in the right abdomen and left lower leg

- John R. Cleary; 110 ft (34 m); upper left chest wound

- Thomas Mark Grace; 225 ft (69 m); struck in left ankle

- Alan Michael Canfora; 225 ft (69 m); hit in his right wrist

- Dean R. Kahler; 300 ft (91 m); back wound fracturing the vertebrae, permanently paralyzed from the chest down

- Douglas Alan Wrentmore; 329 ft (100 m); hit in his right knee

- James Dennis Russell; 375 ft (114 m); hit in his right thigh from a bullet and in the right forehead by birdshot, both wounds minor

- Robert Follis Stamps; 495 ft (151 m); hit in his right buttock

- Donald Scott MacKenzie; 750 ft (230 m); neck wound

In the Presidents Commission on Campus Unrest (pp. 273–274)[32] they mistakenly list Thomas V. Grace, who is Thomas Mark Grace’s father, as the Thomas Grace injured.

All those shot were students in good standing at the university.[32]

Although initial newspaper reports had inaccurately stated that a number of National Guard members had been killed or seriously injured, only one Guardsman, Sgt. Lawrence Shafer, was injured seriously enough to require medical treatment, approximately 10 to 15 minutes prior to the shootings.[33] Shafer is also mentioned in a memo from November 15, 1973. The FBI memo was prepared by the Cleveland Office and is referred to by Field Office file # 44-703. It reads as follows:

Upon contacting appropriate officers of the Ohio National Guard at Ravenna and Akron, Ohio, regarding ONG radio logs and the availability of service record books, the respective ONG officer advised that any inquiries concerning the Kent State University incident should be direct to the Adjutant General, ONG, Columbus, Ohio. Three persons were interviewed regarding a reported conversation by Sgt Lawrence Shafer, ONG, that Shafer had bragged about “taking a bead” on Jeffrey Miller at the time of the ONG shooting and each interviewee was unable to substantiate such a conversation.

In an interview broadcast in 1986 on the ABC News documentary series Our World, Shafer identified the person that he fired at as Joseph Lewis.

Aftermath and long-term effects[edit]

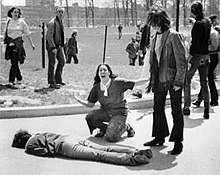

Photographs of the dead and wounded at Kent State that were distributed in newspapers and periodicals worldwide amplified sentiment against the United States’ invasion of Cambodia and the Vietnam War in general. In particular, the camera of Kent State photojournalism student John Filo captured a fourteen-year old runaway, Mary Ann Vecchio, screaming over the body of the dead student, Jeffrey Miller, who had been shot in the mouth. The photograph, which won a Pulitzer Prize, became the most enduring image of the events, and one of the most enduring images of the anti-Vietnam War movement.[citation needed]

The shootings led to protests on college campuses throughout the United States, and a student strike, causing more than 450 campuses across the country to close with both violent and non-violent demonstrations.[8] A common sentiment was expressed by students at New York University with a banner hung out of a window which read, “They Can’t Kill Us All.”[34] On May 8, eleven people were bayonetted at the University of New Mexico by the New Mexico National Guard in a confrontation with student protesters.[35] Also on May 8, an antiwar protest at New York’s Federal Hall held at least partly in reaction to the Kent State killings was met with a counter-rally of pro-Nixon construction workers (organized by Peter J. Brennan, later appointed U.S. Labor Secretary by President Nixon), resulting in the “Hard Hat Riot“.

Just five days after the shootings, 100,000 people demonstrated in Washington, D.C., against the war and the killing of unarmed student protesters. Ray Price, Nixon’s chief speechwriter from 1969–1974, recalled the Washington demonstrations saying, “The city was an armed camp. The mobs were smashing windows, slashing tires, dragging parked cars into intersections, even throwing bedsprings off overpasses into the traffic down below. This was the quote, student protest. That’s not student protest, that’s civil war.”[8] Not only was Nixon taken to Camp David for two days for his own protection, but Charles Colson (Counsel to President Nixon from 1969 to 1973) stated that the military was called up to protect the administration from the angry students; he recalled that “The 82nd Airbornewas in the basement of the executive office building, so I went down just to talk to some of the guys and walk among them, and they’re lying on the floor leaning on their packs and their helmets and their cartridge belts and their rifles cocked and you’re thinking, ‘This can’t be the United States of America. This is not the greatest free democracy in the world. This is a nation at war with itself.'”[8]

Shortly after the shootings took place, the Urban Institute conducted a national study that concluded the Kent State shooting was the single factor causing the only nationwide student strike in U.S. history; over 4 million students protested and over 900 American colleges and universities closed during the student strikes. The Kent State campus remained closed for six weeks.

President Nixon and his administration’s public reaction to the shootings was perceived by many in the anti-war movement as callous. Then National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger said the president was “pretending indifference.” Stanley Karnow noted in his Vietnam: A History that “The [Nixon] administration initially reacted to this event with wanton insensitivity. Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler, whose statements were carefully programmed, referred to the deaths as a reminder that ‘when dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.'” Three days before the shootings, Nixon himself had talked of “bums” who were antiwar protestors on US campuses,[36] to which the father of Allison Krause stated on national TV “My child was not a bum.”[37]

A Gallup Poll taken immediately after the shootings showed that 58 percent of respondents blamed the students, 11 percent blamed the National Guard and 31 percent expressed no opinion.[38]

Karnow further documented that at 4:15 am on May 9, 1970, the president met about 30 student dissidents conducting a vigil at the Lincoln Memorial, whereupon Nixon “treated them to a clumsy and condescending monologue, which he made public in an awkward attempt to display his benevolence.” Nixon had been trailed by White House Deputy for Domestic Affairs Egil Krogh, who saw it differently than Karnow, saying, “I thought it was a very significant and major effort to reach out.”[8] In any regard, neither side could convince the other and after meeting with the students, Nixon expressed that those in the anti-war movement were the pawns of foreign communists.[8] After the student protests, Nixon asked H. R. Haldeman to consider the Huston Plan, which would have used illegal procedures to gather information on the leaders of the anti-war movement. Only the resistance of J. Edgar Hoover stopped the plan.[8]

On May 14, ten days after the Kent State shootings, two black students were killed (and 12 wounded) by police at Jackson State University under similar circumstances – the Jackson State killings – but that event did not arouse the same nationwide attention as the Kent State shootings.[39]

There was wide discussion as to whether these were legally justified shootings of American citizens, and whether the protests or the decisions to ban them were constitutional. These debates served to further galvanize uncommitted opinion by the terms of the discourse. The term “massacre” was applied to the shootings by some individuals and media sources, as it had been used for the Boston Massacre of 1770, in which five were killed and several more wounded.[2][3][4]

On June 13, 1970, as a consequence of the killings of protesting students at Kent State and Jackson State, President Nixon established the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, known as the Scranton Commission, which he charged to study the dissent, disorder, and violence breaking out on college and university campuses across the nation.[40][41]

The Commission issued its findings in a September 1970 report that concluded that the Ohio National Guard shootings on May 4, 1970, were unjustified. The report said:

Even if the guardsmen faced danger, it was not a danger that called for lethal force. The 61 shots by 28 guardsmen certainly cannot be justified. Apparently, no order to fire was given, and there was inadequate fire control discipline on Blanket Hill. The Kent State tragedy must mark the last time that, as a matter of course, loaded rifles are issued to guardsmen confronting student demonstrators.

In September 1970, twenty-four students and one faculty member were indicted on charges connected with the May 4 demonstration at the ROTC building fire three days before. These individuals, who had been identified from photographs, became known as the “Kent 25.” Five cases, all related to the burning of the ROTC building, went to trial; one non-student defendant was convicted on one charge and two other non-students pleaded guilty. One other defendant was acquitted, and charges were dismissed against the last. In December 1971, all charges against the remaining twenty were dismissed for lack of evidence.[42][43]

Legal action against the guardsmen and others[edit]

Eight of the guardsmen were indicted by a grand jury. The guardsmen claimed to have fired in self-defense, a claim that was generally accepted by the criminal justice system. In 1974 U.S. District Judge Frank Battisti dismissed charges against all eight on the basis that the prosecution’s case was too weak to warrant a trial.[7]

Larry Shafer, a guardsman who said he fired during the shootings and was one of those charged, told the Kent-Ravenna Record-Courier newspaper in May 2007: “I never heard any command to fire. That’s all I can say on that.” Shafer—a Ravenna city councilman and former fire chief—went on to say, “That’s not to say there may not have been, but with all the racket and noise, I don’t know how anyone could have heard anything that day.” Shafer also went on to say that “point” would not have been part of a proper command to open fire.

Civil actions were also attempted against the guardsmen, the State of Ohio, and the president of Kent State. The federal court civil action for wrongful death and injury, brought by the victims and their families against Governor Rhodes, the President of Kent State, and the National Guardsmen, resulted in unanimous verdicts for all defendants on all claims after an eleven-week trial.[44] The judgment on those verdicts was reversed by the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on the ground that the federal trial judge had mishandled an out-of-court threat against a juror. On remand, the civil case was settled in return for payment of a total of $675,000 to all plaintiffs by the State of Ohio[45] (explained by the State as the estimated cost of defense) and the defendants’ agreement to state publicly that they regretted what had happened:

In retrospect, the tragedy of May 4, 1970 should not have occurred. The students may have believed that they were right in continuing their mass protest in response to the Cambodian invasion, even though this protest followed the posting and reading by the university of an order to ban rallies and an order to disperse. These orders have since been determined by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to have been lawful.

Some of the Guardsmen on Blanket Hill, fearful and anxious from prior events, may have believed in their own minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

We devoutly wish that a means had been found to avoid the May 4th events culminating in the Guard shootings and the irreversible deaths and injuries. We deeply regret those events and are profoundly saddened by the deaths of four students and the wounding of nine others which resulted. We hope that the agreement to end the litigation will help to assuage the tragic memories regarding that sad day.

In the succeeding years, many in the anti-war movement have referred to the shootings as “murders,” although no criminal convictions were obtained against any National Guardsman. In December 1970, journalist I. F. Stone wrote the following:

To those who think murder is too strong a word, one may recall that even Agnew three days after the Kent State shootings used the word in an interview on the David Frost show in Los Angeles. Agnew admitted in response to a question that what happened at Kent State was murder, “but not first degree” since there was – as Agnew explained from his own training as a lawyer – “no premeditation but simply an over-response in the heat of anger that results in a killing; it’s a murder. It’s not premeditated and it certainly can’t be condoned.”[46]

The Kent State incident forced the National Guard to re-examine its methods of crowd control. The only equipment the guardsmen had to disperse demonstrators that day were M1 Garand rifles loaded with .30-06 FMJ ammunition, 12 Ga. pump shotguns, and bayonets, and CS gas grenades. In the years that followed, the U.S. Army began developing less lethal means of dispersing demonstrators (such as rubber bullets), and changed its crowd control and riot tactics to attempt to avoid casualties amongst the demonstrators. Many of the crowd-control changes brought on by the Kent State events are used today by police and military forces in the United States when facing similar situations, such as the 1992 Los Angeles Riots and civil disorder during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

One outgrowth of the events was the Center for Peaceful Change established at Kent State University in 1971 “as a living memorial to the events of May 4, 1970.”[47] Now known as The Center for Applied Conflict Management (CACM), it developed one of the earliest conflict resolution undergraduate degree programs in the United States. The Institute for the Study and Prevention of Violence, an interdisciplinary program dedicated to violence prevention, was established in 1998.

According to FBI reports, one part-time student, Terry Norman, was already noted by student protesters as an informant for both campus police and the Akron FBIbranch. Norman was present during the May 4 protests, taking photographs to identify student leaders,[48] while carrying a sidearm and wearing a gas mask.

In 1970, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover responded to questions from then-Congressman John Ashbrook by denying that Norman had ever worked for the FBI, a statement Norman himself disputed.[49] On August 13, 1973, Indiana Senator Birch Bayh sent a memo to then-governor of Ohio John J. Gilligan suggesting that Norman may have fired the first shot, based on testimony he [Bayh] received from guardsmen who claimed that a gunshot fired from the vicinity of the protesters instigated the Guard to open fire on the students.[50]

Throughout the 40 years since the shootings, debate has continued on about the events of May 4, 1970.[51][52]

Two of the survivors have died: James Russell on June 23, 2007;[53] and Robert Stamps in June 2008.[54]

Strubbe Tape and further government reviews[edit]

In 2007 Alan Canfora, one of the wounded, located a copy of a tape of the shootings in a library archive. The original 30-minute reel-to-reel tape was made by Terry Strubbe, a Kent State communications student who turned on his recorder and put its microphone in his dorm window overlooking the campus. A 2010 audio analysis of a tape recording of the incident by Stuart Allen and Tom Owen, who were described by the Cleveland Plain Dealer as “nationally respected forensic audio experts,” concluded that the guardsmen were given an order to fire. It is the only known recording to capture the events leading up to the shootings. According to the Plain Dealer description of the enhanced recording, a male voice yells “Guard!” Several seconds pass. Then, “All right, prepare to fire!” “Get down!,” someone shouts urgently, presumably in the crowd. Finally, “Guard! . . . ” followed two seconds later by a long, booming volley of gunshots. The entire spoken sequence lasts 17 seconds. Further analysis of the audiotape revealed that four pistol shots and a violent confrontation occurred approximately 70 seconds before the National Guard opened fire. According to The Plain Dealer, this new analysis raised questions about the role of Terry Norman, a Kent State student who was an FBI informant and known to be carrying a pistol during the disturbance. Alan Canfora said it was premature to reach any conclusions.[55][56]

In April 2012 the United States Department of Justice determined that there were “insurmountable legal and evidentiary barriers” to reopening the case. Also in 2012 the FBI concluded the Strubbe tape was inconclusive because what has been described as pistol shots may have been slamming doors and that voices heard were unintelligible. Despite this, organizations of survivors and current Kent State students continue to believe the Strubbe tape proves the Guardsmen were given a military order to fire and are petitioning State of Ohio and U.S. Government officials to reopen the case using independent analysis. The organizations do not desire to prosecute or sue individual guardsmen believing they are also victims.[57][58]

Memorials and remembrances[edit]

Each May 4 from 1971 to 1975 the Kent State University administration sponsored an official commemoration of the events. Upon the university’s announcement in 1976 that it would no longer sponsor such commemorations, the May 4 Task Force, a group made up of students and community members, was formed for this purpose. The group has organized a commemoration on the university’s campus each year since 1976; events generally include a silent march around the campus, a candlelight vigil, a ringing of the Victory Bell in memory of those killed and injured, speakers (always including eyewitnesses and family members), and music.

On May 12, 1977, a tent city was erected and maintained for a period of more than 60 days by a group of several dozen protesters on the Kent State campus. The protesters, led by the May 4 Task Force but also including community members and local clergy, were attempting to prevent the university from erecting a gymnasium annex on part of the site where the shootings occurred seven years earlier, which they believed would alter and obscure the historical event. Law enforcement finally brought the tent city to an end on July 12, 1977, after the forced removal and arrest of 193 people. The event gained national press coverage and the issue was taken to the U.S. Supreme Court.[61]

In 1990, twenty years after the shootings, a memorial commemorating the events of May 4 was dedicated on the campus on a 2.5 acre (10,000 m²) site overlooking the University’s Commons where the student protest took place.[62] Even the construction of the monument became controversial and, in the end, only 7% of the design was constructed. The memorial itself does not contain the names of those killed or wounded in the shooting; under pressure, the university agreed to install a plaque near it with the names.[63][64]

In 1999, at the urging of relatives of the four students killed in 1970, the university constructed an individual memorial for each of the students in the parking lot between Taylor and Prentice halls. Each of the four memorials is located on the exact spot where the student fell, mortally wounded. They are surrounded by a raised rectangle of granite[65]featuring six lightposts approximately four feet high, with the student’s name engraved on a triangular marble plaque in one corner.[66]

George Segal’s 1978 cast-from-life bronze sculpture, In Memory of May 4, 1970, Kent State: Abraham and Isaac was commissioned for the Kent State campus by a private fund for public art,[67] but was refused by the university administration who deemed its subject matter (the biblical Abraham poised to sacrifice his son Isaac) too controversial. The sculpture was accepted in 1979 by Princeton University, and currently resides there between the university chapel and library.[68]

An earlier work of land art, Partially Buried Woodshed,[69] was produced on the Kent State campus by Robert Smithson in January 1970.[70] Shortly after the events, an inscription was added that recontextualized the work in such a way that it came to be associated by some with the event.

In 2004, a simple stone memorial was erected at Plainview-Old Bethpage John F. Kennedy High School in Plainview, New York, which Jeffrey Miller had attended.

On May 3, 2007, just prior to the yearly commemoration, an Ohio Historical Society marker was dedicated by KSU president Lester Lefton. It is located between Taylor Hall and Prentice Hall between the parking lot and the 1990 memorial.[71] Also in 2007, a memorial service was held at Kent State in honor of James Russell, one of the wounded, who died in 2007 of a heart attack.[72]

In 2008, Kent State University announced plans to construct a May 4 Visitors’ Center in a room in Taylor Hall.[73]

A 17.24-acre (6.98 ha) area was listed as “Kent State Shootings Site” on the National Register of Historic Places on February 23, 2010.[59] Places normally cannot be added to the Register until they have been significant for at least fifty years, and only cases of “exceptional importance” can be added sooner.[74] The entry was announced as the featured listing in the National Park Service‘s weekly list of March 5, 2010.[75] Contributing resources in the site are: Taylor Hall, the Victory Bell, Lilac Lane and Boulder Marker, The Pagoda, Solar Totem, and the Prentice Hall Parking Lot.[60] The National Park Service stated the site “is considered nationally significant given its broad effects in causing the largest student strike in United States history, affecting public opinion about the Vietnam War, creating a legal precedent established by the trials subsequent to the shootings, and for the symbolic status the event has attained as a result of a government confronting protesting citizens with unreasonable deadly force.”[9]

Every year on the anniversary of the shootings, notably on the 40th anniversary in 2010, students and others who were present share remembrances of the day and the impact it has had on their lives. Among them are Nick Saban, head coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide football team who was a freshman in 1970;[76]surviving student Tom Grace, who was shot in the foot;[77] Kent State faculty member Jerry Lewis;[78] photographer John Filo;[31] and others.

Cultural references[edit]

Documentary[edit]

- 1970 – Confrontation at Kent State (director Richard Myers) – documentary filmed by a Kent State University filmmaker in Kent, Ohio, directly following the shootings.

- 1971 – Allison (director Richard Myers) – a tribute to Allison Krause.

- 1979 – George Segal (director Michael Blackwood) – documentary about American sculptor George Segal; Segal discusses and is shown creating his bronze sculpture Abraham and Isaac, which was originally intended as a memorial for the Kent State University campus.

- 2000 – Kent State: The Day the War Came Home (director Chris Triffo, executive producer Mark Mori), the Emmy-Award-winning documentary featuring interviews with injured students, eyewitnesses, guardsmen, and relatives of students killed at Kent State.

- 2007 – 4 Tote in Ohio: Ein Amerikanisches Trauma (“4 dead in Ohio: an American trauma”) (directors Klaus Bredenbrock and Pagonis Pagonakis) – documentary featuring interviews with injured students, eyewitnesses and a German journalist who was a U.S. correspondent.

- 2008 – How It Was: Kent State Shootings – National Geographic Channel documentary series episode.

- 2010 – Fire In the Heartland: Kent State, May 4, and Student Protest in America (director Daniel Lee Miller) – documentary featuring the build-up to, the events of, and the aftermath of the shootings, told by many of those who were present and in some cases wounded.

Film and television[edit]

- 1970 – The Bold Ones: The Senator – a television program starring Hal Holbrook, aired a two-part episode titled “A Continual Roar of Musketry” which was based on a Kent-State-like shooting. Holbrook’s Senator character is conducting an investigation into the incident.

- 1974 – The Trial of Billy Jack – The climactic scene of this film depicts National Guardsmen lethally firing on unarmed students, and the credits specifically mention Kent State and other student shootings

- 1981 – Kent State (director James Goldstone) – television docudrama

- 1995 – Nixon – Directed by Oliver Stone, the film features actual footage of the shootings; the event also plays an important role in the course of the film’s narrative.

- 2000 – The ’70s starring Vinessa Shaw and Amy Smart, a mini-series depicting four Kent State students affected by the shootings, as they move through the decade[79]

- 2002 – The Year That Trembled (written and directed by Jay Craven; based on a novel by Scott Lax), a coming-of-age movie set in 1970 Ohio, in the aftermath of the Kent State killings[80]

- 2009 – In the opening credits of Watchmen, the shootings are briefly shown.[81] The scene consists of a young woman putting a flower into the barrel of one of the guard’s guns, just before they all go off.

- 2013 – Freedom Deal: The Story of Lucky,[82][83] a historical drama made in Cambodia by filmmaker Jack RO, is the only existing onscreen dramatization to date which depicts the 1970 US-ARVN incursion into Cambodia* (*the inciting incident for the Kent State Shootings) from a Cambodian point of view. Archival US military radio audio mentions the evolving Kent State situation while the Cambodian protagonists make their way through the conflict.

Literature[edit]

Graphic novels[edit]

- 1977 – Kent State: A Requiem by J. Gregory Payne. First performed in 1976. Told from the perspective of Bill Schoeder’s mother, Florence, this play has been performed at over 150 college campuses in the U.S. and Europe in tours in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s; it was last performed at Emerson College in 2007. It is also the basis of NBC’s award-winning 1981 docudrama Kent State.[citation needed]

- 1993 – Blanket Hill explores conversations of the National Guardsmen hours before arriving at Kent State University…activities of students already on campus…the moment they meet face to face on May 4, 1970…framed in the trial four years later. The play originated as a classroom assignment, initially performed at the Pan-African Theater and was developed at the Organic Theater, Chicago. Produced as part of the Student Theatre Festival 2010, Department of Theatre and Dance, Kent State University, it was again designed and performed by current theatre students as part of the 40 May 4 Commemoration. The play was written and directed by Kay Cosgriff. A DVD of the production is available for viewing from the May 4 Collection at Kent State University.[citation needed]

- 1995 – Nightwalking. Voices From Kent State by Sandra Perlman, Kent, Franklin Mills Press, first presented in Chicago April 20, 1995, (Director: Jenifer (Gwenne) Weber). Kent state is referenced in Nikki Giovanni‘s “The Beep Beep Poem”.[citation needed]

- 2010– David Hassler, director of the Wick Poetry Center at Kent State and theatre professor Katherine Burke teamed up to write the play May 4 Voices, in honor of the incident’s 40th anniversary.[citation needed]

- 2012- 4 Dead in Ohio: Antigone at Kent State (created by students of Connecticut College‘s theatre department and David Jaffe ’77, associate professor of theater and the director of the play) – An adaptation of Sophocles‘ Antigone using the play Burial at Thebes by Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney. It was performed Nov. 15-18, 2012 in Tansill Theater.[citation needed]

- The incident is mentioned in Allen Ginsberg‘s 1975 poem Hadda be Playin’ on a Jukebox.

- The poem “Bullets and Flowers” by Yevgeny Yevtushenko is dedicated to Allison Krause.[84] Krause had participated in the previous days’ protest during which she reportedly put a flower in the barrel of a Guardsman’s rifle,[84] as had been done at a war protest at The Pentagon in October 1967, and reportedly saying, “Flowers are better than bullets.”

- Peter Makuck‘s poem “The Commons” is about the shootings. Makuck, a 1971 graduate of Kent State, was present on the Commons during the incident.[citation needed]

- Gary Geddes’ poem Sandra Lee Scheuer remembers one of the victims of the Kent State shootings.

- Janet Ruth Heller’s poem “For Mary Vecchio, 1973” portrays Vecchio as a modern Mary praying over the fallen students. This poem was first published inCanticum Novum (1973)[citation needed] and reprinted in Janet Ruth Heller’s book, Folk Concert (2012).[85]

The best known popular culture response to the deaths at Kent State was the protest song “Ohio“, written by Neil Young for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. The song was written, recorded, and preliminary pressings (acetates) were rushed to major radio stations, although the group already had a hit song, “Teach Your Children“, on the charts at the time. Within two-and-a-half weeks of the Kent State shootings, “Ohio” was receiving national airplay. Crosby, Stills, and Nashvisited the Kent State campus for the first time on May 4, 1997, where they performed the song for the May 4 Task Force’s 27th annual commemoration. The B-side of the single release was Stephen Stills’ anti-Vietnam War anthem “Find the Cost of Freedom”.

There are a number of lesser known musical tributes, including the following:

- Harvey Andrews‘ 1970 song “Hey Sandy”[86] was addressed to Sandra Scheuer.lyrics

- Steve Miller’s “Jackson-Kent Blues,”[87] from The Steve Miller Band album Number 5 (released in November 1970), is another direct response.

- The Beach Boys released “Student Demonstration Time“[88] in 1971 on Surf’s Up. Mike Love wrote new lyrics for Leiber & Stoller‘s “Riot in Cell Block Number Nine.”

- Bruce Springsteen wrote a song called “Where Was Jesus in Ohio” in May or June 1970. The unreleased and uncirculating song is reported to be the artist’s emotionally charged response to the Kent State shootings.[89]

- Jon Anderson has said that the lyrics of “Long Distance Runaround” (on the album Fragile by Yes, also released in 1971) are also in part about the shootings, particularly the line “hot colour melting the anger to stone.”[90]

- Pete Atkin and Clive James wrote “Driving Through Mythical America”, recorded by Atkin on his 1971 album of the same name, about the shootings, relating them to a series of events and images from 20th-century American history.[citation needed]

- In 1970–71 Halim El-Dabh, a Kent State University music professor who was on campus when the shootings occurred, composed Opera Flies, a full-length opera, in response to his experience. The work was first performed on the Kent State campus on May 8, 1971, and was revived for the 25th commemoration of the events in 1995.

- Album Everyone, by British band Everyone, released in January 1971 included song Don’t Get Me Wrong by Andy Roberts about Kent State shootings.[91][92]

- In 1971, the composer and pianist Bill Dobbins (who was a Kent State University graduate student at the time of the shootings), composed “The Balcony”, an avant-garde work for jazz band inspired by the same event, according to the album’s liner notes.[93] First performed in May 1971 for the university’s first commemoration, it was released on LP in 1973 and was performed again by the Kent State University Jazz Ensemble in 2000 for the 30th commemoration.[citation needed]

- Dave Brubeck‘s 1971 cantata Truth Is Fallen is dedicated to the slain students at Kent State University and Jackson State University; the work was premiered in Midland, Michigan on May 1, 1971, and released on LP in 1972.[94]

- The All Saved Freak Band dedicated its 1973 album My Poor Generation to “Tom Miller of the Kent State 25.” Tom Miller was a member of the band who had been featured in Life magazine as part of the Kent State protests and lost his life the next year in an automobile accident.

- Holly Near‘s “It Could Have Been Me” was released on A Live Album (1974). The song is Near’s personal response to the incident.[95]

- The industrial band Skinny Puppy‘s 1989 song “Tin Omen” on the album Rabies refers to the event.

- Lamb of God’s 2000 song “O.D.H.G.A.B.F.E.” references Kent State, together with the Auschwitz concentration camp, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the Waco siege.

- A commemorative 2-CD compilation featuring music and interviews was released by the May 4 Task Force in May 2005, in commemoration of the 35th anniversary of the shootings.[96]

- Joe Walsh, who briefly attended Kent State, has said that he wrote “Turn to Stone” in response to the shootings.[citation needed] He also mentions the event in the song “Decades” (1992).

- One of the students who participated in the protest was Chrissie Hynde, future leader of The Pretenders, who was a sophomore at the time.[97] Her former bandmate,[98] Mark Mothersbaugh, and Gerald Casale, founding members of Devo, also attended Kent State at the time of the shootings. Casale was reportedly “standing about 15 feet (4.6 m) away”[99] from Allison Krause when she was shot, and was friends with her and another one of the students who were killed. The shootings were the transformative moment for him[100] and for the band, which became less of a pure joke and more a vehicle for social critique (albeit with a blackly humorous bent).[99]

- Sage Francis references the Kent State shootings in his song “Slow Down Gandhi.”

- Gwar references the Kent State shootings in the song “Slaughterama” saying “Good thing I was such an expert shot with the National Guard back at Kent State, I bagged four that day.”

- Genesis recreates the events from the perspective of the Guards in the song “The Knife“, on Trespass (October 1970).[citation needed] Against a backdrop of voices chanting “We are only wanting freedom”, a male voice in the foreground calls “Things are getting out of control here today”, then “OK men, fire over their heads!” followed by gunshots, screaming and crying. The song became a concert mainstay, and established Genesis on the prog-rockscene.[citation needed]

- Barbara Dane sings “The Kent State Massacre” written by Jack Warshaw on her 1973 album I Hate the Capitalist System.[101]

- The Swedish rock band Gläns över Sjö & Strand made a song about the shootings, in the album Är du lönsam lilla vän?, called “Ohio 4 maj 1970”.[102][103]

- Lodi, New Jersey-based horror punk band Mourning Noise mentions this event in its song “Radical” recorded live for the album “Death Trip Delivery”.[citation needed]

- Experimental punk rock band At the Drive-In reference the shooting in their song “Alpha Centauri” singing, “students spray the kent state mist/wishing wills missing clientele/widows six legged lost and found”.

- Chris Butler of The Waitresses and Tin Huey was among a crowd of students fired on.[104]

- Ryan Harvey, a member of the Riot-Folk collective, wrote “Kent State Massacre (13 Seconds in May)” which was included in his 2004 album The Revolution Will Not Be Amplified.[105]

- Jeff Powers’ song “13 Seconds 67 Shots”, written on the 40th anniversary of the killings in a style similar to Neil Young’s “Ohio“, was released in February 2012.[106]

Photography[edit]

- In her 1996 still/moving photographic project Partially Buried in three parts, visual artist Renée Green aims to address the history of the shootings both historically and culturally.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b “May 4th Memorials”. Kent State University. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ a b “These would be the first of many probes into what soon became known as the Kent State Massacre. Like the Boston Massacre almost exactly two hundred years before (March 5, 1770), which it resembled, it was called amassacre not for the number of its victims but for the wanton manner in which they were shot down.” Philip Caputo (May 4, 2005). “The Kent State Shootings, 35 Years Later”. NPR. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ a b Rep. Tim Ryan (May 4, 2007). “Congressman Tim Ryan Gives Speech at 37th Commemoration of Kent State Massacre”. Congressional website of Rep. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio). Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ a b John Lang (May 4, 2000). “The day the Vietnam War came home”. Scripps Howard News service. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ Darrell Laurent, “Kent State – A history lesson that he teaches and lives – Dean Kahler disabled during 1970 student demonstration at Kent State University”, Accent on Living, Spring 2001. Accessed at [1][dead link].

- ^ “Sandy Scheuer”. May4archive.org. 1970-05-04. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis, Jerry M.; Thomas R. Hensley (Summer 1998). “The May 4 Shootings At Kent State University: The Search For Historical Accuracy”(Reprint). Ohio Council for the Social Studies Review 34 (1): 9–21. ISSN 1050-2130. OCLC 21431375. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Director: Joe Angio (February 15, 2007). Nixon a Presidency Revealed (television). History Channel.

- ^ a b “Weekly Highlight 03/05/2010 Kent State Shootings Site, Portage County, Ohio”.

- ^ “Chronology of events”. May 4 Task Force. May 4 Task Force. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ “Kent State 1970:Description of Events May 1 through May 4”. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, 1970. Special Report KENT STATE. “Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion were not Kent State students. There is also evidence to suggest that the burning was planned beforehand: railroad flares, a machete, and ice picks are not customarily carried to peaceful rallies.”–Page 251.

- ^ “ROTC building arson May 2, 1970: Witness statements taken August 6, 1970, p. 6”. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “ROTC building arson May 2, 1970: Witness statements taken August 6, 1970, p. 4”. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “ROTC building arson May 2, 1970: Witness statements taken August 6, 1970, p. 5”. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Payne, J. Gregory (1997). “Chronology”. May4.org. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Sharkey, Mary Anne; Lamis, Alexander P. (1994). Ohio politics. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-87338-509-8. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Icons-mini-file_acrobat.gif); padding-right: 18px; background-position: 100% 50%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat; “>”President’s Commission on Campus Unrest – pp. 253–254” (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ Caputo, Philip (2005). 13 Seconds : A Look Back at the Kent State Shootings/with DVD. Chamberlain Bros. ISBN 1-59609-080-4.

- ^ May 4 Task Force members. “KENT STATE, 1970: description of events May 1 through May 4”. May4.org. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Eszterhas, Joe; Michael D. Roberts (1970). Thirteen seconds; confrontation at Kent State. New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 121. ISBN 0-396-06272-5.OCLC 108956.

- ^ “Chronology, May 1–4, 1970”. Kent State University. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Krause v. Rhodes, 471 F.2d 430 (United States Court of Appeals, 6th Cir. 1974).

- ^ Bills, Scott (1988). Kent State/May 4: Echoes Through a Decade. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-87338-278-1.

- ^ “TRIALS: Last Act at Kent State”. Time. September 8, 1975. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ John Kifner (May 4, 1970). “4 Kent State Students Killed by Troops”. The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, p. 289.

- ^ “Kent State Shootings: 1970 Year in Review”. Upi.com. January 27, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Kent State Shootings: 1970 Year in Review”. Upi.com. January 27, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “The Kent State Shootings and the “Move the Gym” Controversy, 1977″. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ a b “Kent State shootings remembered”. CNN. May 5, 2000. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ a b http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Icons-mini-file_acrobat.gif); padding-right: 18px; background-position: 100% 50%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat; “>”The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, William W. Scranton, Chairman, US Government Printing Office, 1970. Retrieved April 20, 2011.” (PDF). Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “U.S. Justice Department 1970 Summary Of FBI Reports (truthful excerpts)”. May4.org. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “1970 Timeline”. New York University. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press (May 10, 1970). “Arsonists Strike on 2 Campuses”. The Modesto Bee. pp. A–2. Retrieved December 5, 2010. “National Guardsmen were withdrawn from the University of New Mexico late Friday after a confrontation with students that sent 11 people to the hospital with bayonet wounds.”

- ^ de Onis, Juan (May 1, 1970). “Nixon puts ‘bums’ label on some college radicals”. The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ “histcontext”. Lehigh.edu. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Campus Unrest Linked to Drugs Palm Beach Post May 28, 1970”. Google. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Killings at Jackson State University!”. The African American Registry. 2005. Archived from the original on December 1, 2006. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Icons-mini-file_acrobat.gif); padding-right: 18px; background-position: 100% 50%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat; “>The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest(Subscription). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1970.ISBN 0-405-01712-X. Retrieved April 30, 2011. This book is also known as The Scranton Commission Report.

- ^ “1970 Year in Review”. Upi.com. January 27, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Home”. Burr.kent.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ Pacifico, Michael; Kendra Lee Hicks Pacifico. “Chronological summary of events”. Mike and Kendra’s May 4, 1970, Web Site. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Tim Phillips, “Attorney for Students who were Shot at Kent State Dies in New York”, Activist Defense, March 8, 2013.

- ^ Neil, Martha, “Joseph Kelner, attorney who sued sitting Ohio governor over Kent State slayings, is dead at 98”, ABAJournal, March 8, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- ^ Stone, I.F. (December 3, 1970). “Fabricated Evidence in the Kent State Killings”. The New York Review of Books 15 (10). ISSN 0028-7504.OCLC 1760105.

- ^ “Center for Applied Conflict Management”. CACM Homepage. January 29, 2007. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Renner, James (May 3, 2006). “The Kent State Conspiracies: What Really Happened On May 4, 1970?”. Cleveland Free Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Canfora, Alan (March 16, 2006). “US Government Conspiracy at Kent State – May 4, 1970”. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ Verifying documents are in the Special Collections archive at the Kent State University library.

- ^ Corcoran, Michael (May 4, 2006). “Why Kent State is Important Today”. The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Stang, Alan (1974). “Kent State:Proof to Save the Guardsmen” (Reprint).American Opinion. ISSN 0003-0236. OCLC 1480501. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ http://fairuse.100webcustomers.com/fairenough/oregon01.html

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ John Mangels (October 8, 2010). “Kent State tape indicates altercation and pistol fire preceded National Guard shootings (audio)”. Cleveland Plain Dealer. Cleveland.com. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ Maag, Christopher (May 11, 2010). “Ohio: Analysis Reopens Kent State Controversy”. The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ Northeast Ohio. “May 4th wounded from Kent State shootings want independent review of new evidence Cleveland Plain Dealer May 3, 2012”. Cleveland.com. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ John Mangels, The Plain Dealer (May 9, 2010). “New analysis of 40-year-old recording of Kent State shootings reveals that Ohio Guard was given an order to prepare to fire”. Cleveland Plain Dealer. Blog.cleveland.com. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c “Announcements and actions on properties for the National Register of Historic Places for March 5, 2010”. Weekly Listings. National Park Service. March 5, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Seeman, Mark F.; Barbato, Carole; Davis, Laura; and Lewis, Jerry (December 31, 2008). http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Icons-mini-file_acrobat.gif); padding-right: 18px; background-position: 100% 50%; background-repeat: no-repeat no-repeat; “>”National Register of Historic Places Registration: Kent State Shootings Site” (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ “Tent City and Gym Struggle”.

- ^ “May 4 Memorial (Kent State University)”. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “May 4 Memorial Controversy”. May41970.com. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ May 4 Memorials: Eyewitnesses react[dead link]

- ^ “Prentice Lot May 1999”. January 27, 2001. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Pacifico, Michael; Kendra Lee Hicks Pacifico (2000). “Prentice Lot Memorial Dedication, September 8, 1999”. Mike and Kendra’s May 4, 1970, Web Site. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “Abraham and Isaac”. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Sheppard, Jennifer (1995). “Strolling Among Sculpture on Campus”. The Princeton Patron. Princeton Online. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ “Photograph”. Robertsmithson.com. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ Gilgenbach, Cara (April 15, 2005). “Robert I. Smithson, Partially Buried Woodshed, Papers and Photographs, 1970–2005″. Kent State University Libraries and Media Services, Department of Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ O’Brien, Dave (2007-05-03). “State honors historic KSU site with plaque near Taylor Hall”. Written at Kent, Ohio. Record-Courier (Kent and Ravenna, Ohio). pp. A1, A10. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ Steve Duin (July 1, 2007). “The long road back from Kent State”. The Oregonian. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ “Associate Provost’s Perspective”. Einside.kent.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ National Register Criteria for Evaluation, National Park Service. Accessed 2013-02-28.

- ^ “Weekly List Actions”. National Park Service. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Lopresti, Mike (May 3, 2010). “May 4 shootings still follow former Kent State football players”. USA Today. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Kirst, Sean (May 4, 2010). “Kent State: ‘One or two cracks of rifle fire … Oh my God!'”. The Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York). Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Adams, Noah (May 3, 2010). “Shots Still Reverberate For Survivors Of Kent State”. NPR. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ “The 70s DVD”. Lions Gate. 2000. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ “Synopsis of The Year That Trembled“. AMC-TV. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Zack Snyder (2009). Watchmen (DVD) (in English). Paramount. About 7 minutes in.

- ^ “IMDB”.

- ^ “website”.

- ^ a b Yevtushenko, Yevgeny (May 2002). “Bullets and Flowers” (translated by Anthony Kahn). The Kudzu Monthly. Archived from the original on April 21, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Heller, Janet Ruth (2012). Folk Concert. Cochran GA: Anaphora Literary Press. p. 32.

- ^ Andrews, Harvey. “Hey Sandy” (MP3 excerpt from song).HarveyAndrews.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Miller, Steve. “Jackson-Kent Blues”. lyrics.org. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Love, Mike. “Student Demonstration Time”. ocap.ca. Ontario Coalition Against Poverty. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ “SpringsteenLyrics.com”. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Anderson, Jon. “Ask Jon Anderson”. JonAndersdon.com. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ 8/Ù. “Members of the Liverpool Scene: Andy Roberts”. Mekons.de. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Andy Roberts”. colin-harper.com. September 19, 1970. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Textures – Bill Dobbins”. Unearthed in the Atomic Attic. June 30, 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ “May 1–4, 2002”. Composers Datebook. May 1, 2002. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ “Holly Near – It Could Have Been Me (Live)”. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ “Purchase link for CD”. May 2005.

- ^ “Behind the Music 1970” (Kent State portion, hosted at May 4 Archive).VH1: Behind the Music. VH1.

- ^ “Pretenders”. The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. Simon & Schuster. 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Olson, Steve (July 2006). “DEVO and the evolution of The Wipeouters: interview with Mark Mothersbaugh”. Juice: Sounds, Surf & Skate.OCLC 67986266. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ “Biography of May 4 speakers”. KentWired. May 2, 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2010. “Casale told DrownedInSound.com, an online music magazine, that May 4, 1970, was the day he stopped being a hippie. ‘It was just so hideous,’ he said. ‘It changed everything: no more mister nice guy.'”

- ^ “Barbara Dane Discography”. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ^ “Ohio 4 Maj 1970 by Gläns över sjö & strand on Spotify”. Open.spotify.com. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Gläns Över Sjö & Strand – Är Du Lönsam Lille Vän? (1970)”. Progg.se. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ “Chris Butler: Biography”. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ “Music – Ryan Harvey”. Riotfolk. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ “13 Second 67 Shots (Kent State Massacre) | Jeff Powers”. Jeffpowers.bandcamp.com. 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2013-05-12.